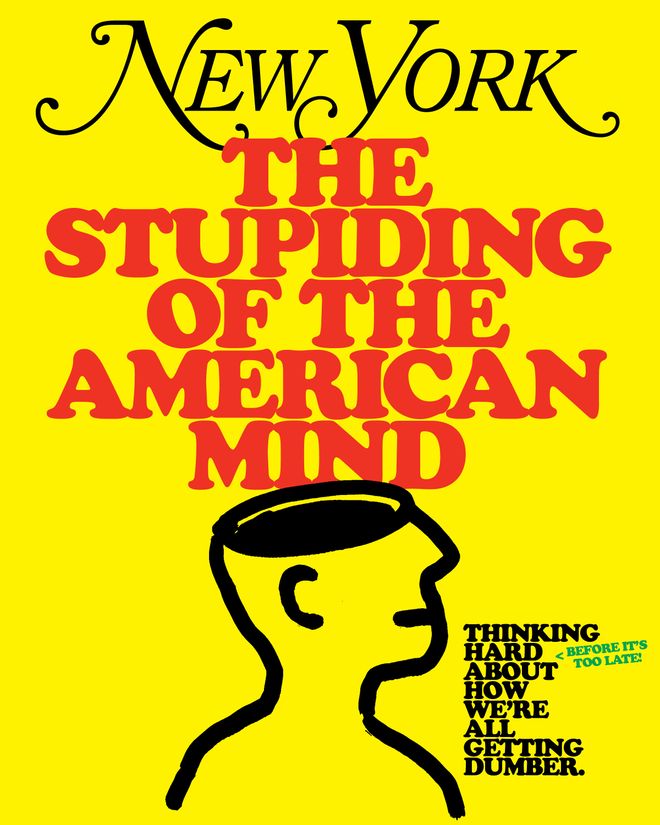

A Theory of Dumb

Length: • 17 mins

Annotated by Mark Isero

Some content could not be imported from the original document. View content ↗

This article was featured in New York’s One Great Story newsletter. Sign up here.

Experts were sure that the 20th century would make us stupid. Never before had culture and technology reshaped daily life so quickly, and every new invention brought with it a panic over the damage it was surely causing to our fragile, defenseless brains. Lightbulbs, radio, comic books, movies, TV, rock and roll, video games, calculators, pornography on demand, dial-up internet, the Joel Schumacher Batmans — all of these things, we were plausibly warned, would turn us into drooling idiots.

The test results told a different story. In the 1930s, in the U.S. and across much of the developed world, IQ scores started creeping upward — and they kept on going, rising on average by roughly three points per decade. These gains accumulated such that even an unexceptional bozo from the turn of the millennium would, on paper, look like a genius compared to his Depression-era ancestors. This phenomenon came to be known as the Flynn effect, after the late James Flynn, the social scientist who noticed it in the 1980s.

Because these leaps appeared over just a few generations, Flynn ruled out genetics as their cause. Evolutionary change takes hundreds of thousands of years, and the humans of 1900 and 2000 were running on the same basic mental hardware. Instead, he posited that there had been a kind of software update, uploaded to the collective mind by modern life itself. Better education trained students to reason with hypotheticals instead of just memorizing facts. Office and industrial jobs required workers to grapple with ideas rather than physical objects. Mass media exposed audiences to unfamiliar places and perspectives. People got better at classifying, generalizing, and thinking beyond their own daily experience, which are some of the basic skills IQ tests are designed to measure. Flynn liked to illustrate this shift from literalism toward abstraction with the example that, a century ago, if you asked someone what dogs and rabbits have in common, they might answer “Dogs hunt rabbits,” not “They’re both mammals.”

Maybe, then, all the noise and novelty wasn’t rotting our minds but upgrading them. (Studies suggest that better nutrition and reduced exposure to lead may have also helped.) In any case, the Flynn effect held steady for so long and through so many apparent threats that there was no reason to believe it wouldn’t last forever, even if, someday, somebody invented a chatbot that could do homework or Theo Von started podcasting.

Or so thought Elizabeth Dworak, now an assistant professor at Northwestern University’s medical school, when she chose the topic of her 2023 master’s thesis. She decided to analyze the results of 394,378 IQ tests taken in the U.S. between 2006 and 2018 to see if they exhibited the same climb. “I had all this cognitive data and thought, Hey, there’s probably a Flynn effect in there,” she says. But when she ran the numbers, “I felt like I was in Don’t Look Up,” the movie in which an astronomy grad student played by Jennifer Lawrence discovers a comet speeding toward Earth. “I spent weeks going back through all the code. I thought I’d messed something up and would have to delay submitting. But then I showed my adviser, and he said, ‘Nope, your math is right.’”

The math showed declines in three important testing categories, including matrix reasoning (abstract visual puzzles), letter and number series (pattern recognition), and verbal reasoning (language-based problem-solving). The first two, in which losses were deepest, measure what psychologists call fluid intelligence, or the power to adapt to new situations and think on the fly. The drops showed up across age, gender, and education level but were most dramatic among 18-to-22-year-olds and those with the least amount of schooling.

Dworak knows what her findings suggest, but as a scientist, she’s required to add a few caveats. First, scores weren’t down in every category. They rose in spatial reasoning, or the ability to mentally rotate 3-D objects, which is crucial for playing Fortnite. Second, her data came from voluntary unproctored online tests. “This wasn’t like an SAT. Somebody could have been taking it on a bus,” she says. “But I did have almost 400,000 data points.” Third and most important, “we can’t exactly say that people are getting dumber, just that scores in these categories are going down.” IQ has always been a rough proxy for intelligence, less a direct gauge than a reflection of certain mental habits that society rewards. Its scales are renormalized every decade or so and its meaning constantly debated among statisticians, some of whom still wonder if both the original Flynn effect and its reversal might owe more to inconsistent methodology than to real cognitive change.

“So I spoke with reviewers who were really well established in the field, and I got great feedback, and I was able to add some wonderful nuance so I wasn’t just publishing clickbait,” says Dworak. “And then after the paper came out, it was funny. Most of the reaction among both academics and laymen was like, ‘Oh, IQ scores are down? I could have told you that.’”

The world is dumber, and we all know it. Lately, it feels like that culturewide upgrade to our mental operating systems has been rolled back to an older and buggier version.

Stupidity, like intelligence, is a nebulous thing, hard to define but easy to spot in the wild. It’s not just that children have been bombing their standardized tests (ACT scores are at their lowest in more than 30 years, and high-school seniors’ average math scores in a national exam were the lowest since 2005) or that more than a quarter of U.S. adults now read at the lowest proficiency level. It’s also that in nearly all aspects of life, we’re opting for routines, entertainment, and entire belief systems that ask less and less of our brains. The stigma that was once attached to ignorance has disappeared, and the loudest and least informed voices now shape the conversation, forcing everyone else to learn to speak their language.

For example, polls suggest as much as a quarter of the electorate is now composed of so-called low-information voters — the type who can’t name their representatives and get most of their news from memes but tend to be more persuadable than their better-informed neighbors. That makes them all-powerful in swing elections, provided campaigns can reach them with a message simple and arousing enough to resonate with what little else they know.

In finance, economic fundamentals have become meaningless as investors have adopted the Dada-esque illogic of crypto, treating the stock market like a Ouija board and moving their money wherever they assume the stupidest among them will. The latest result is a Ponzi-shaped AI bubble that almost nobody can justify with a straight face. Yet when Jensen Huang, CEO of Nvidia, the premier AI stock, was recently photographed eating at a Korean-fried-chicken restaurant, shares of unrelated Korean-fried-chicken companies jumped up to 30 percent, which, by the rules of the current market, seems perfectly rational.

It’s tempting to blame all this on the pandemic, an unprecedented stress test on human minds. We emerged blinking into the daylight after spending years on our couches, staring into screens, and repeatedly catching a virus with neurological side effects only to find that our attention spans had been chopped in half, our kids’ grades had cratered, and all of our friends had spent their lockdowns woodshedding some pretty wild theories about 5G and pasteurized milk. But while that lost stretch surely did damage, the brain fog we stumbled into had been gathering for years. The trend lines were in place well before 2020.

This probably isn’t evolution, either. We’re not living in an Idiocracy-style scenario where the dumbest people are just having more babies. A 2018 study of Norwegian families found that both the long rise and the recent decline in IQ scores have been observed within families; children were scoring higher or lower than their parents in ways that matched broader trends. So if, as James Flynn argued, the IQ surge of the 20th century was caused by environmental factors, its reversal almost certainly is too.

Those environmental factors could include anything from changes in education, nutrition, family structure, and economic pressures to a cocktail of potentially brain-damaging exposures — microplastics, antidepressants, wildfire smoke. But in 2025, the consensus is that the factor to blame is the thing in our pockets.

For most of us, our phone has become both an external hard drive, storing everything we used to remember, and a portable Las Vegas, ensuring we never have to suffer a boring minute. It feels like it must be frying some cognitive circuitry, but proving that in a lab has been harder than expected. The brain is a noisy, high-variance organ, and most of the research on it is observational. A 2022 analysis in Nature found that many of the studies of the past two decades linking behavior to brain structure or function were too small to be trusted, usually based on just a couple dozen participants. To detect real effects with confidence, you’d need a sample size into the thousands. (This hasn’t stopped papers from generating splashy headlines about how smartphones and their apps are allegedly “rewiring our brains.”) Even the entrenched idea that social media floods our reward centers with dopamine — similar to drugs, sex, or gambling — is on shaky ground. “I’m not aware of any within-person study that shows dopamine levels modulate as a function of social-media consumption,” says Scott Marek, a researcher at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and a co-author of the 2022 Nature paper.

But even if our phones aren’t literally resculpting our gray matter, most of us assume they must be contributing to some kind of cognitive atrophy by distracting us from more mentally demanding activities. That idea agrees with some of the data — including a recent poll showing that the number of Americans who read for pleasure has fallen by 40 percent over the past two decades — but it might also be a bit self-flattering. It’s not as if, before the release of the iPhone, we were all sitting around doing recreational calculus or working our way through Finnegans Wake. If you dig into that poll, it turns out that only 28 percent of Americans say they were reading books for fun back in 2004, and that year most of them were probably just reading The Da Vinci Code.

A lot of today’s thinking on our digitally addled state leans heavily on Marshall McLuhan and Neil Postman, the hepcat media theorists who taught us, in the decades before the internet, that every new medium changes the way we think. They weren’t wrong — and it’s a shame neither of them lived long enough to warn society about video podcasts — but they were operating in a world where the big leap was from books to TV, a gentle transition compared to what came later. As a result, much of the current commentary still fixates on devices and apps, as if the physical delivery mechanism were the whole story. But the deepest transformation might be less technological than social: the volume of human noise we’re now wired into.

Maybe it’s not that our cognitive software has been downgraded so much as we’ve turned off our firewalls. Everybody in the developed world now has Airdrop access to everyone else’s mind. If we are getting dumber, there’s a good chance we made each other that way.

The human brain reached something like its modern form at least 10,000 years ago, by the end of the Upper Paleolithic period, when people lived in tribes of between 20 and 50 and rarely ran into anyone else. We were programmed by evolution to process the faces, feelings, and gossip of small groups. Even as recently as the 1990s, most people interacted with only their relatives, co-workers, and friends each day, plus maybe their local news anchor on TV. Now, though, those same Paleolithic brains are being bombarded with the thoughts of hundreds of strangers every hour. Modern communication in all its forms has put us in contact with more minds than we were built to handle, and our own seem to be wilting under the load.

Not so long ago, the dolts among us were free to think their thoughts quietly to themselves with no easy way to share them. At worst, a person would usually just embarrass himself in front of his own family or bowling team. Bad ideas had a harder time scaling and reproducing, so lots of stupidity stayed local, and everyone else could happily overestimate the average person’s intelligence because they saw less of it. But then we connected everyone on the planet and gave them each the equivalent of their own printing press, radio station, and TV network. Now, even those with nothing useful to say can tell the whole world exactly, or more often vaguely, what they think.

To be clear, this isn’t nostalgia for a time when fewer voices were heard. The widening of the conversation has been, in some ways, a good thing: more perspectives, more accountability, the Rizzler’s TikToks. But the downside is that we can see the full distribution of human thought in one infinite scroll, and it turns out the median is lower than we ever could’ve imagined. In theory, this is the democratization of expression. In practice, it feels like a crowdsourced lobotomy.

The problem isn’t any one device or platform or influencer, and you can’t escape it just by quitting Instagram or unsubscribing from all your paid newsletters. The unavoidable reality is that a massive decentralized swarm of people is now talking, arguing, and opining all at once, everywhere, all the time. And if you want to say anything, or simply understand what’s going on, you have to pass through them. The medium is still the message, but the medium, today, is the mob.

This might seem like something that’s been happening for a while, and it has been, but some recent shifts suggest we’ve crossed a kind of threshold. In June, the Reuters Institute reported that social media is now Americans’ main source of news, surpassing legacy outlets for the first time. TikTok is a trusted news source for 17 percent of people worldwide. And even those numbers undersell how dramatic the transition has been and how weird our informational ecosystem has become. The shrinking ranks of traditional media have hidden themselves behind paywalls, and changes to the recommendation engines at Google, Facebook, and X have made it harder than ever for readers to even find their work, assuming anyone cares to when their feeds are already overflowing with entertainment, nonsense, and infinite subgenres of increasingly specific pornography. And layered on top of all that is President Trump’s ongoing embrace of Steve Bannon’s “flood the zone with shit” strategy, which fills every channel with static and then cranks up the volume.

To push any nutritional information through the noise, what you need isn’t expertise or reporting or original thought; it’s compression. The winners are the people who can boil complicated phenomena down to the smallest units: a podcaster summarizing a secondhand anecdote, a TikToker explaining geopolitics in 23 seconds, a quote tweet of a screenshot of an excerpt, a top Reddit comment, a YouTube essay plagiarizing that Reddit comment, a bar chart that somehow encapsulates everything about the moment we’re living in. Our first point of contact with most information is rarely the information itself but some lossily compressed derivative that’s already been processed and strained through a dozen layers of reinterpretation.

As a consumer, it’s hard to escape this cycle, since in their fight for survival, traditional outlets have themselves joined the race to compress themselves and reprocess. There’s less reporting and more commentary about reporting, and sometimes just commentary about that commentary. What used to be a pyramid of original reporting topped by a layer of interpretation has flipped upside down into a wide base of takes wobbling on a shrinking nub of facts.

Not all of this summarizing is bad, and plenty of it is necessary. But when each filter compresses and distorts what came before it, the compressions and distortions add up. Try to follow anything — a scientific paper, a celebrity quote, a breaking-news headline — as it moves through the internet’s intestines, and you’ll see its meaning disintegrate. Each leap between one aggregator and the next and across different platforms results in new mutations and misunderstandings.

Ask Dworak. When her paper on the reverse Flynn effect was published in 2023, it was picked up by the parenting website Fatherly, which, to its credit, at least tried to preserve some of her nuance. The site’s blog post explained that a decline in IQ scores doesn’t necessarily mean people are becoming less intelligent, but it ran under a slightly confusing curiosity-gap headline, “American IQs Are Dropping. Here’s Why It Might Not Be a Bad Thing.” Then, Dworak says, “Tucker Carlson, who was still on Fox News at the time, did a segment about the study and cited the Fatherly article.” Somehow viewers took Dworak to be claiming it was good that IQ scores were falling — “so I got a bunch of tweets calling me despicable.”

We’ve become so accustomed to this churn that much of what we know, or think we know, now consists of confabulations that have built up over years. The collective knowledge base has been overwritten with received wisdom, fourth-hand opinions, and counterintuitive pop social science that flatters our cleverness while sparing us the effort of understanding anything deeply. In an increasingly complex world, the metaphors we use to explain it keep getting cruder. Any process that turns anything to crap is “enshittification.” Every aesthetic is a “core.” The ad-driven, data-powered personalization system that rules our lives is “the algorithm.” Anything that can’t be explained via one of the above is simply “vibes.”

All of this TL;DR compression is about to be made even worse by the “slop” — another overly broad classifier — disgorged by AI large language models. But in the meantime, the technology, which also absorbs giant quantities of the internet’s excreta and tries to think with it, might offer a clue to how this environment is affecting us. We don’t yet know how similar LLMs are to the human brain; maybe the only thing they truly have in common is that we don’t fully understand how either works. But even if they don’t think like us, they seem to degrade like us.

This year, a team of researchers at the University of Texas at Austin, Texas A&M, and Purdue University fed LLMs months’ worth of popular or low-quality tweets — including ones categorized as “conspiracy theories, exaggerated claims, unsupported assertions” or composed in a style that does “not encourage in-depth thinking” — and found that it induced a form of what they called “brain rot.” The models exhibited “worse reasoning, poorer long-context understanding, diminished ethical norms, and emergent socially undesirable personalities.” They began to “skip thoughts,” jumping to conclusions without going through the reasoning steps that got them there. Even their algebra skills got worse. As Junyuan Hong, one of the study’s authors, explains, this “is not really what you learn from Twitter.”

Another experiment with possible implications for our brain rot was conducted by Ilia Shumailov, an AI-security scientist and former senior research scientist at Google DeepMind, who set out to understand what would happen if LLMs huffed too much of their own exhaust. Shumailov had been thinking about a Catch-22 of artificial intelligence, which goes like this: LLMs require massive amounts of high-quality human-created text to train on, which AI companies collect by scraping the internet, often indiscriminately. Now, though, a growing share of the web’s data is itself generated by AI; by one recent count, about half of the articles and listicles posted online in 2025 were written by chatbots. This means future LLMs will learn by ingesting the compressed and degraded knowledge produced by their predecessors and their own regurgitations will, in turn, train the models that follow. Over time, this feedback loop could rot the foundation of the original training data as traces of human thinking are diluted by machine-spun drivel.

To see what that might look like, Shumailov ran an experiment in which he taught ten generations of LLMs almost exclusively on text produced by their predecessors. Unsurprisingly, they got worse with each cycle. Imagine visiting a library where all the books had been replaced by high-schoolers’ book reports and then the next day finding only summaries of those reports written by raccoons. Shumailov’s models gradually lost touch with the logic of their original training data, each inheriting and amplifying the errors of the one before it. As their corpus of knowledge thinned and warped, the models became “overfit,” an AI term for when a model becomes so fixated on its narrow education that it loses the ability to generalize, like a student who can memorize the answers to a practice test but is helpless on the real one. (A separate 2021 study argued that the human brain, like an LLM, can become overfit to the repetitive specifics of daily life, making it harder to handle unfamiliar situations — so our dreams may be nature’s way of injecting some surrealist noise into our datasets to keep our cognitive machinery limber.) Eventually, they just belched out nonsense — and did so with increasing confidence. In a paper published last year, Shumailov called this “model collapse,” a process by which an AI system becomes, in his words, “poisoned with its own projection of reality.”

I floated to Shumailov my theory that humans may be in a state of model collapse; that they, too, are poisoning themselves. He says he needs to see more data. “There is definitely a lot more communication happening online, but whether the information being produced is lower quality is a question we should measure precisely, because without using the scientific method, I think it’s very hard to hypothesize,” he says. At the same time, he did find that, as his work made its way across the internet, some of its original meaning was lost. “There are as many opinions as there are people, and yes, some folks did misunderstand.”

Shumailov’s paper went viral, or at least as viral as an academic study about tainted AI-training data can go. It also became mildly controversial. Some researchers argued that his experiment was an oversimplification: After all, it’s unlikely that real human data will ever disappear completely, and big AI companies already guard against that possibility by screening their training sets for AI-generated text and weighing higher-quality sources more heavily. A different research team later ran a similar experiment but slipped a copy of the original human data into every training round, a tweak that easily prevented collapse. So for most LLMs, the danger of model collapse might be more theoretical than existential, but the irony is hard to miss. Some of the very same companies that so vigilantly protect their own LLMs from junk inputs — Google, Meta, and X, say — seem much less worried about the junk they’re feeding human users.

So maybe all the stupidity we’re feeling right now is a matter of training data. Last century’s popular media forms — books, films, TV, newspapers — demanded our attention and imagination. They made the world feel larger and more complicated than the version inside our heads. In effect, they were teaching the very abstract-reasoning skills that IQ tests measure. Today’s media does almost the opposite. Instead of expanding our sense of the world, it shrinks it down, placing each of us at the center of our own private universe, surrounded by voices that insist everything is simpler than it really is.

Then again, who cares? It feels a little quaint to worry about this stuff right now, just as all of society seems to be downgrading its view of intelligence. “My friends and I were joking about how being smart isn’t as sexy as it used to be,” Dworak tells me. “Now people just care more about things like how many subscribers you have on Twitch.”

If the Flynn effect was partly a story about society encouraging and rewarding certain cognitive habits — abstraction, analysis, sustained attention — those rewards are now disappearing. AI is encroaching on high-paying knowledge work: It is already stealing jobs from entry-level coders with doctors, lawyers, and bankers likely next. Tenured posts in academia are disappearing as schools adjunctify and research funding dries up. Anti-elitism has turned wonkishness and expertise into a political liability, which is bad news for the Democrats’ crowded bench of professorial Obama impersonators. If you’d invested a few hundred dollars into Dogecoin instead of the S&P ten years ago, you could have retired by now.

Perhaps the 21st century is teaching us to a different test. Despite what I just finished saying, there is one compressionary artifact from the internet that may perfectly encapsulate everything about our present moment: the “midwit” meme. It’s a three-panel bell curve in which a simpleton on the left makes a facile, confident claim and a serene, galaxy-brained monk on the right makes a distilled version of the same claim — while the anxious try-hard in the middle ties himself in knots pedantically explaining why the simple version is actually wrong. Who wants to be that guy?