The Great Massachusetts Nicotine Prohibition

Length: • 10 mins

Annotated by Mark Isero

Mark Isero: Do we have a freedom to smoke?

Born after 2000? You can't buy cigarettes or vapes in Brookline—ever—and other towns are following suit. Are generational nicotine bans brilliant public health policy or government overreach? Bay State lawmakers will soon decide.

On a recent Wednesday afternoon, my friend Caroline and I embarked on a brazen mission in Brookline: to buy a vape pen. We zigzagged through twentysomethings shuffling to and from Blank Street Coffee and Anna’s Taqueria until we made our way to a Sunoco gas station. Caroline (who asked not to use her last name given the stigma surrounding nicotine use) pulled out her ID and asked for a Crave vape. The cashier responded with a shake of his head. “2001? Nope,” he said. “I can’t sell this to you.”

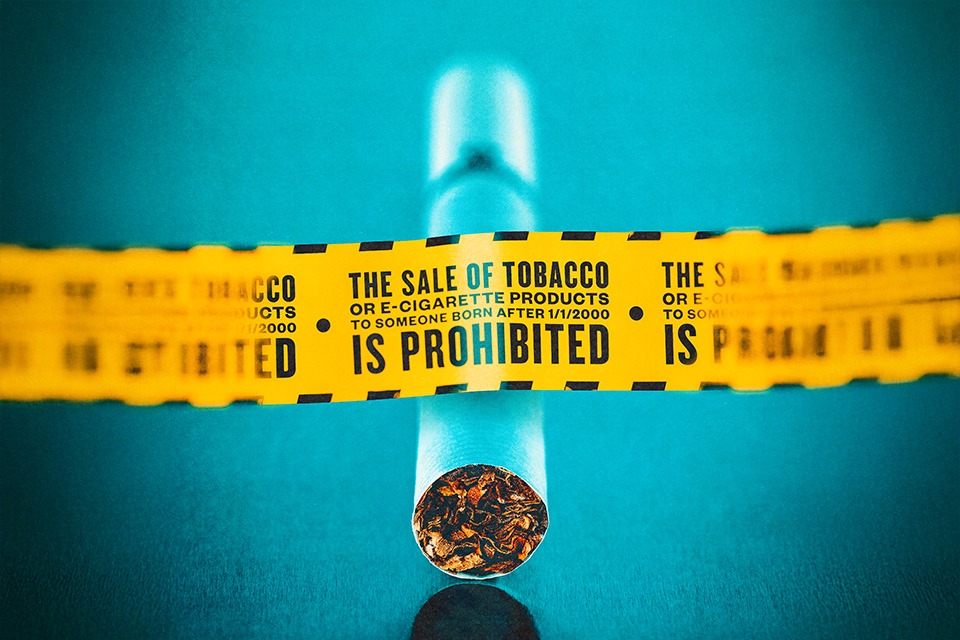

Caroline is 24, well over the 21-year-old legal age that we saw clearly listed on a sign to the left of the mini mart’s front door. Yet there was another sign inside the store. It was printed on plain white paper, emblazoned with the Brookline town seal, and read: “The sale of tobacco or e-cigarette products to someone born on or after 1/1/2000 is prohibited.”

In 2021, Brookline started a quiet anti-nicotine revolution as the first municipality in the world to implement and uphold a version of the “Nicotine-Free Generation” policy, an idea whose seeds were first sown by the surgeon general in the 1980s. Designed to stop the next generation—and beyond—from getting hooked on nicotine, it cuts people off by birth year rather than age. That means if you were born on or after January 1, 2000, you can never buy tobacco or e-cigarette products in Brookline at any point or for any reason for the rest of your life. For now, the law effectively splits the adult population in two: those who can and those who can’t, people who might be separated in age by only a day. Eventually, as time goes by, no one here will be able to buy themselves a nic fix.

In response to the restriction, local retailers (including the Sunoco Caroline and I visited on our little mission) sued Brookline over the legality of the bylaw. The case made its way up to the Supreme Judicial Court, with Brookline prevailing in 2024. That decision paved the way for more than a dozen other towns (including Somerville, Chelsea, Needham, and Newton) to adopt similar policies. Now there are bills before the legislature that, if passed, would prevent anyone born after January 1, 2006, from ever buying nicotine products (aside from those that are FDA-approved) anywhere in Massachusetts.

Innovative yet controversial, tobacco-control legislation like this is old hat for Massachusetts, which was a leader not only with the smoke-free workplace law in the early aughts but also with raising the legal purchase age to 21 and the ban on all flavored tobacco products, including menthol cigarettes. “We want to continue to build on what’s been done before. I believe the next frontier is this Nicotine-Free Generation policy,” says state Senator Jason Lewis, who represents towns north of Boston and is behind the Senate version of this bill on Beacon Hill. “If this becomes law, it will contribute to the ongoing cultural shift away from using tobacco [and nicotine] products.”

Meanwhile, groups like Cambridge Citizens for Smokers’ Rights—and plain ol’ citizens in general—fear the policy is a clear example of the government going too far, calling the ban everything from downright ridiculous to one that robs people of their individual freedoms guaranteed under the U.S. Constitution. Some municipalities, including Worcester and Bellingham, seem to agree, shooting down proposals for Nicotine-Free Generation policies in their communities. Now, opponents of the bans—supported by convenience-store trade associations worried about a loss of sales revenue—are upping the ante, seeking to pass a state law amendment that would nullify these municipal bans altogether.

It’s safe to say that the battle lines have been drawn on nicotine—and it’s getting ugly. But is Massachusetts leading a revolution to save us from the dangers of tobacco and nicotine, or are these policies just the latest step toward becoming a full-blown nanny state?

Last May, nearly 100 Reading residents packed into their town hall, spilling out of the meeting room and into the hallway and an overflow area next door. A film crew from Korea captured it all for Tobacco War, a documentary looking at Massachusetts’ world-leading tobacco-control efforts. On the agenda that evening: a proposed amendment to the Board of Health’s tobacco sales regulation that would ban the sale of e-cigarette or tobacco products—which includes all products containing nicotine—to anyone born on or after January 1, 2004.

The long list of speakers included Mark Gottlieb, executive director of Northeastern University School of Law’s Public Health Advocacy Institute, which has worked extensively on tobacco policy and clinical addiction, as well as Harvard doctors and professors, select board members and Reading residents. Kathleen O’Leary, a Reading nurse practitioner who has specialized in nicotine dependence for the past 13 years, was one of the few who spoke. “I used to just see cigarette users, and I now see vaping or cigarette and vape users,” she testified to the board. “I’m seeing more youth than adults triple-using: cigarette, vape, and Zyn.” When it was time to vote a few weeks later, the Board of Health passed the ban 4 votes to 1. Reading suddenly became the next Massachusetts community to lock an entire generation out of nicotine.

The logic, according to anti-nicotine advocates, is pretty straightforward: If you want to break the cycle of addiction, you have to stop it before it starts. What worries health professionals most is nicotine’s highly addictive quality—considered on par with heroin. Meanwhile, despite copious research on the effects of tobacco, there isn’t any long-term data on the effects of nicotine on its own, yet health experts warn it can cause cardiovascular problems and alter brain chemistry—something of particular concern for teens and young adults with still-developing brains.

When it comes to tobacco, there is little need to rehash its well-established negative health effects—for smokers themselves and bystanders alike—nor those of the mouth-cancer-causing chewing tobacco and dip. While tobaccoless nicotine products like e-cigarettes might help users avoid the harmful effects of tobacco (in fact, they were originally designed to help wean people off it), the problem is that’s not who’s actually using them. According to the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), of the adults younger than 25 years who reported current e-cigarette use, 72 percent had never even smoked a combustible cigarette.

What’s more insidious, nicotine opponents complain, is that companies intentionally market their products toward a younger generation that’s barely at the legal age to smoke. Take the Ooze Movez wireless speaker-vape pen combo (did we mention it lights up in rainbow colors, too?), or vapes shaped like guitars or teddy bears, or the countless teen-friendly flavors of vape cartridges (though the sales of these are already banned in Massachusetts), from passion-fruit lemonade to tropical rainbow blast.

In turn, this marketing approach has prompted advocates to push for an urgent policy response. They say there is more than enough to worry about when it comes to nicotine and no reason to wait to act until decades-long longitudinal studies are completed. “It may be determined in the future to be more dangerous than smoking,” says Maureen Buzby, a regional tobacco inspection coordinator in Melrose and prominent advocate for the municipal Nicotine-Free Generation policies across the Mystic Valley. “We don’t have decades of data, but should we wait to have decades of data before we try to stop this, or should we just let it happen and then find out how bad it was?”

The masterminds behind Nicotine-Free Generation policies have arguably hit a stroke of strategic legislative genius. Their bans are almost always passed by Boards of Health—where the right of approval lies only with a select few board members, sometimes as few as three. Even more advantageous for ban supporters is the fact that those most prominently affected by the bill can’t advocate against it. After all, many of them are too young to buy nicotine or tobacco products, can’t vote, and aren’t really in a position to speak out against it—at least not without getting in trouble with their parents. That night in Reading, not a single person who would be affected by the ban stood up to oppose it. And perhaps not surprisingly, half a dozen under-21 regular vapers who live in towns where bans exist declined my requests to speak for this story.

This town-by-town strategy has proven successful in Massachusetts before. It was used to get lawmakers to pass the smoke-free workplace law in 2004 and again in 2018, when the state became the sixth state to raise the legal smoking age to 21. Both of these policies faced backlash in their time, a response that is viewed by some advocates as par for the course for any boundary-breaking initiative. “In Massachusetts, local communities become incubators for new public health policies; it’s just the way we’re set up here. It’s been a tradition,” Gottlieb says. “I think if we can get somewhere between 50 and 100 towns and cities to take this on, it will make it a lot easier for the state legislature to go forward.”

The ultimate goal? Nothing short of social transformation. “Now, here in Massachusetts, we can’t imagine going into a restaurant, bar, nail salon, school, or hospital where people are smoking. That’s the goal of this nicotine policy,” Buzby says. “We’re hoping that a generation down the road feels the same way about smoking as we do about seeing people smoke in our workplace—that it just is something wildly unimaginable.”

Even if the true health risks of nicotine are still unknown, opponents say the dangers of passing such a ban are abundantly clear. “We’re talking about a future generation of adults who are going to be restricted from making choices, and it actually doesn’t really even matter what that choice is,” says Emily Weija, a supporter of Cambridge Citizens for Smokers’ Rights, an advocacy group that has been fighting anti-tobacco legislation for about 20 years. For her and many others, the issue is less about tobacco or nicotine and more about personal agency. “What other things are we going to restrict adults from choosing? It just infantilizes a future generation.”

Oh, and if those principled objections weren’t enough, there’s a far more practical problem: The bans are basically useless. Just ask Jeffrey Singer, a senior fellow in the department of health policy studies at the DC-based libertarian think tank the Cato Institute. “It’s not going to work,” he says, adding that the bans might even “stimulate an illicit market, which is going to make using these substances more dangerous to the people who use them.”

Turns out he has a point. Massachusetts already has a booming illicit nicotine market. At a raid earlier this year in Dorchester, for instance, authorities seized 700 packs of unstamped menthol cigarettes, along with cocaine and cannabis. “We’ve created such a thriving marketplace that illegal sellers are coming here,” says Peter Brennan, executive director of the New England Convenience Store and Energy Marketers Association. “And they’re targeting Massachusetts.”

Then there’s the cross-border shopping problem. Thanks to the state’s menthol cigarette ban, consumers have already learned that they can easily cross state lines to buy whatever they want. As a result of the 2020 ban, consumption of menthol cigarettes dropped a mere 5 percent—not much of a behavioral shift. What did change, though, was where smokers bought them: Sales decreased in the Bay State and increased in bordering ones, according to a JAMA Internal Medicine report.

It wasn’t lost on us that my friend could have legally bought cannabis in Brookline yet not a nicotine vape pen.

Still, the real irony hit me that afternoon out with Caroline. After we got booted from the Sunoco, we kept walking until, a few minutes later, we came across one of Brookline’s cannabis dispensaries. We didn’t go in, but it wasn’t lost on us that Caroline could have bought a federally illegal substance in Brookline yet not a nicotine vape pen, which is a legal product across the nation. “Adults in Massachusetts are deemed competent to choose to buy alcohol or marijuana. Both of these are intoxicants,” says Stephen Helfer, head of Cambridge Citizens for Smokers’ Rights. “But according to the Nicotine-Free Generation policy, they don’t feel adults have the judgment to purchase tobacco or nicotine products. And tobacco and nicotine do not intoxicate people.”

The inconsistency gets even weirder when you consider that, though the jury is still out on the long-term health or cancer-causing effects of nicotine, as Singer points out, alcohol was recently deemed a carcinogen by the U.S. Surgeon General. Yet no moves have been made for a generational ban on alcohol. (After all, we all know how that kind of prohibition went last time.)

Unsurprisingly, opponents of the ban have gone beyond just complaining—they’ve gone on the offensive. In mid-January, Lynn Representative Daniel Cahill and Senator William Driscoll filed counter-bills—supported by the New England Convenience Store and Energy Marketers Association, the Retailers Association of Massachusetts, and the Massachusetts Package Stores Association, among others. Their proposed law amendment aims to strengthen the state’s 21-plus age restriction on tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, and gambling, making it the law of the land to “preempt, supersede, or nullify” any town-based policies. That means no town could legally go further than Massachusetts law, and all current Nicotine-Free Generation policies would be null and void. “It’s hard enough to do business in Massachusetts already. There’s already enough government regulation of our lives, and this is just one more step,” says Brennan, who notes that his member retailers are losing more than $100 million in revenue every year as a result of the menthol and flavor ban currently in effect. “I think common sense prevails at the state level.” (These bills, as well as the Nicotine-Free Generation policies, are awaiting legislative committee review.)

For Caroline, the cashier who denied her a vape in Brookline was just a small bump in the road. We walked a short 10 minutes until we crossed over into Boston and popped into the Bluemoon Smoke Shop, where my friend easily purchased what she was looking for. Not a fan of nicotine, I looked on with slight disapproval but said nothing. In my opinion, the way it should be.

This article was first published in the print edition of the August 2025 issue with the headline: “Does Nanny Know Best?”