They Burn Books to Burn Us Too

Length: • 13 mins

Annotated by Mark Isero

Notes From The Undrowned

The Global War on Black Memory

I. The Flame That Never Dies

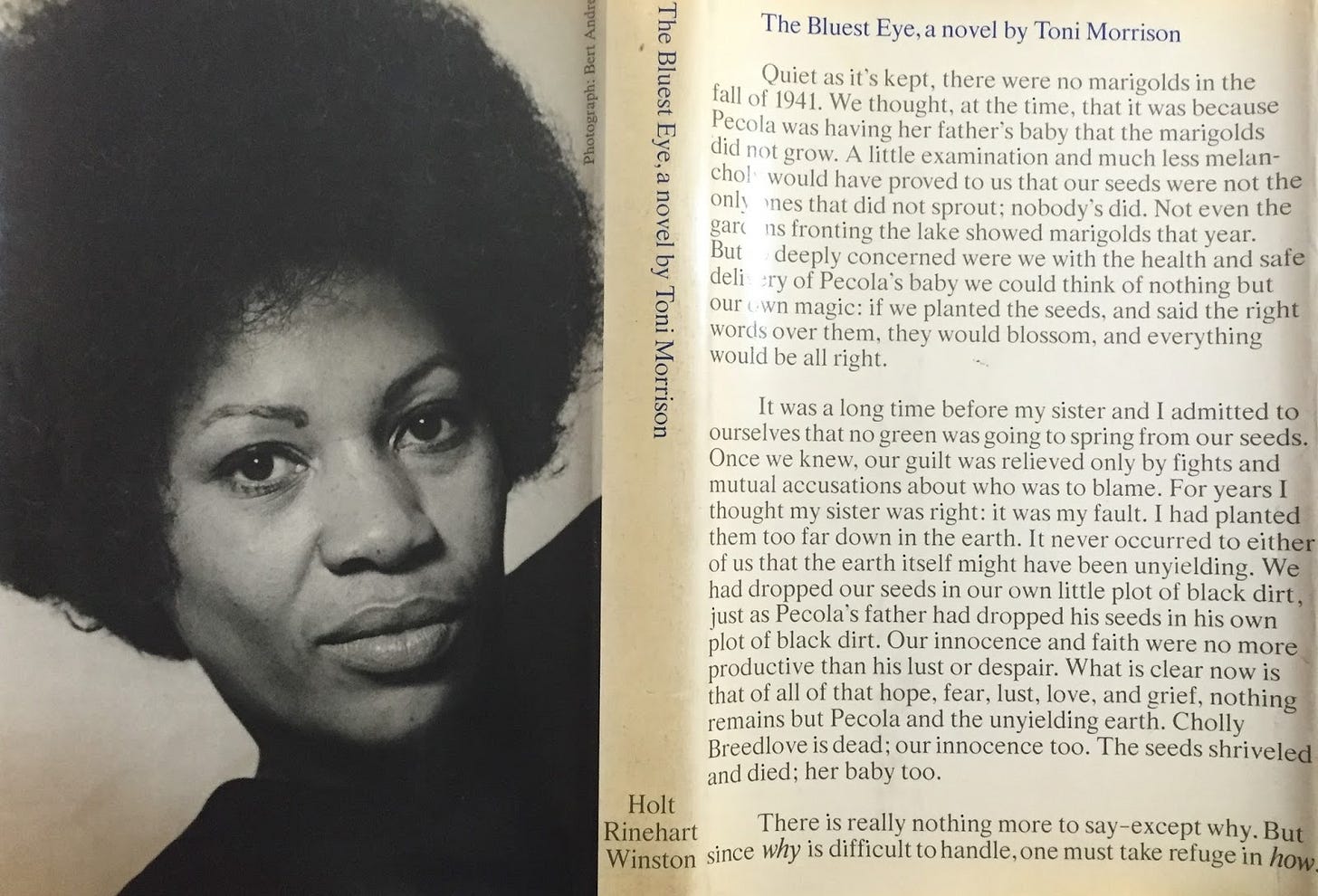

The first time I held a “banned book,” I didn’t know it was dangerous. I was in High School. The cover was soft and creased like an old hymn book. The pages smelled of something older than paper—maybe wood, maybe blood. It was The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison. I had taken it from our public library in Hempstead, New York, the kind of place where the heating half-worked in winter but the librarians knew your name, your birthday, your mother’s birthday, and the exact shelf where your soul might be hiding in fiction.

I remember reading that first chapter and feeling the air change—like God had walked into the room, barefoot and breathless. I didn’t know then that some people wanted to bury what I had just touched. I didn’t know that entire states would one day strike Morrison from the classroom like a curse. I didn’t know that the truth could be illegal.

But I felt it. Even then. That heat.

Years later, I would watch as school boards across the country began their slow violence—banning Black authors, cutting Black history units, turning “critical race theory” into a ghost to hunt. They said they wanted to protect the children. But it was only certain children they meant. Not mine. Not me. Not the children who walk into classrooms carrying the weight of a lineage they’re not allowed to name.

What I know now is this: when a government begins to fear its own history, it has already declared war on the people who survived it.

This erasure is not new. It is not uniquely American. It is not about debate—it is about domination. Across time and borders, regimes have always burned books to burn bodies. They have banned memory in hopes of breeding silence. The Nazis did it in 1933, the Apartheid regime did it in 1953, the United States has done it—again and again—in every century it has breathed. And now, in the shadow of a rising global authoritarianism, it happens once more.

This is not a culture war.

This is a war on memory. And memory is survival. Memory is where the dead whisper instructions. Memory is the way we walk forward without sinking. So when they come for the stories, they come for our skin, too.

They want to make forgetting feel like patriotism. They want to unwrite us.

But what they do not know is that we were never written in the first place. We were sung. We were carved into tree trunks and kitchen counters and braided into our mother’s hair. We are older than their archives. And our stories do not end with silence.

They begin in fire.

II. To Burn a Book Is to Burn a Body

There is a photograph—black and white, blurred at the edges like it’s trying to forget itself. In it, German students are throwing books into a bonfire. They are smiling. Some wear uniforms, some plain clothes, but all of them carry the same expression: righteousness.

May 10, 1933. A fire crackled in the heart of Berlin. Students in crisp uniforms tossed more than 25,000 books into a pyre meant to purify the German soul. They fed the flames with the words of Freud, Marx, Einstein, and Du Bois. What was burned wasn’t just paper, but possibility. The possibility that another story might be told—one that did not sanctify the Reich.

The Ministry of Propaganda, headed by Joseph Goebbels, understood the stakes of memory. To shape a nation, you must first shape what it remembers. The Nazis didn’t just burn books—they rewrote textbooks. They erected a single story: Aryan, pure, mythic.

Du Bois, Black and brilliant, was a threat in both Berlin and Birmingham. His works, banned in Germany, were hounded in America. The fire, like empire, crossed oceans.

Before the fires, Heinrich Heine had already warned them, a century earlier: “Where they burn books, they will, in the end, burn human beings.”

The Nazis understood something that modern white supremacists also know: that the destruction of people begins with the destruction of truth. Books are not just objects. They are repositories of resistance. They teach the child to ask: Why does the world look like this? Who made it this way? And who paid the price? When you destroy the record of who bled, you make it easier to bleed them again.

But Germany was not alone.

In 1953, the apartheid regime in South Africa passed the Bantu Education Act. Its purpose was clear: to institutionalize ignorance. Black children were taught just enough to serve. Enough math to sweep floors. Enough reading to follow orders. But never enough to dream.

Steve Biko called it plainly: “The most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.”

In Biko’s country, to know your history was to risk your life. The names of Black heroes were erased. The languages of the ancestors were silenced. What remained was a hollowed-out identity, designed by white hands and imposed at gunpoint.

And still—students marched. Books were hidden like weapons. Learning became rebellion.

The American playbook was older still.

In the antebellum South, it was illegal to teach enslaved Africans to read. Slave codes punished literacy with whipping or worse. The ability to write one's name was a revolutionary act. What terrified white plantation owners wasn’t just rebellion, it was the possibility that their captives might document it.

Later, during the Jim Crow era, the rewriting of history became a civic religion. The Dunning School, a group of white historians recast Reconstruction as a tragic mistake, portraying freed Black people as lazy, corrupt, or childlike. Their textbooks became national curriculum. They wrote Black excellence out of the record and Black suffering into a footnote. They replaced truth with nostalgia, and nostalgia is the most dangerous kind of lie because it demands to be loved.

In each of these regimes—Nazi, apartheid, American white supremacist—the goal was not only control, but the elimination of imagination. Because to remember fully is to imagine differently. And to imagine differently is to resist.

To burn a book is to burn a body.

To ban a history is to ban a future.

And to silence a story is to say: You do not exist.But we remember.

We remember with broken spines and dog-eared pages. We remember through quilt patterns, through songs hummed while stirring the pot, through church fans bearing the names of our dead. We remember because remembering is the only way the lost make it home.

III. The Curriculum of Control: Erasure Today

If history is a wound, then curriculum is the bandage—or the blade.

In 2022, the state of Florida passed the “Stop W.O.K.E. Act,” a law designed to limit discussions of race in public schools and workplaces. The legislation bars educators from teaching that anyone “must feel guilt, anguish, or other forms of psychological distress” because of historical actions committed by members of their race. What sounds like protection is, in truth, projection—shielding whiteness from the emotional residue of its own inheritance.

But guilt is not the enemy. Oblivion is.

In the same state, a high school Advanced Placement African American Studies course was rejected by the Florida Department of Education for containing topics like Black Queer Studies and the Movement for Black Lives. In their words, the course “lacks educational value.” That is to say: Black people thinking critically about their lives is unacceptable. That is to say: Black joy, Black theory, Black resistance—disqualified.

And Florida is not alone.

Across the country, from Texas to Tennessee, states have introduced a wave of legislation banning so-called “divisive concepts” in classrooms. These laws are rarely clear, intentionally vague so that fear becomes a form of governance. Teachers are left unsure what they can say. Students are robbed of context. And truth—fragile, wounded, but still breathing—is slowly suffocated.

What is happening is not random. It is coordinated.

Groups like Moms for Liberty and conservative think tanks such as the Heritage Foundation have made it their mission to whitewash history under the guise of “parental rights.” But which parents? Which rights? What about the right of Black children to know they were once kings and queens, mathematicians, midwives, and makers of stars? What about their right to know that before they were enslaved, they were sacred?

Instead, we see libraries pulled apart. Books by Black, Indigenous, Latinx, queer, and trans authors quietly disappear from shelves. Students are told that discussing racism is itself a form of racism. Educators are punished for honoring the dead. And the government—our government—stands complicit in a war of forgetting.

This is not just censorship. This is state-sanctioned amnesia.

We are being taught not to remember Trayvon. Not to remember Sandra. Not to remember the Atlantic as a graveyard. Not to remember that America was not built by its founders, but by its fugitives. That democracy here has always been unfinished work. That freedom is not given but gathered, in the mouths of mothers, in the fists of children, in the breath between “I can’t” and “I will.”

When they ban books, they ban a mirror.

When they silence a lesson, they silence a lineage.

When they rewrite the syllabus, they attempt to rewrite the soul.But we have read the margins before.

We have survived without the textbook.

We know how to teach in whispers, in basements, in barbershops and church pews.What they erase, we rebuild.

What they forbid, we remember.

IV. Where Memory Lives: Resistance as Archive

They have always tried to burn us, but the ash refused to scatter.

Long before we were permitted to read, we were remembering. In hush harbors and under moonlight, memory traveled not through paper but through people. The griot, the elder, the preacher, the mama at the stove—all became librarians of the unwritten. The story didn’t need a school board’s approval to be gospel. It needed only breath.

And breath, for us, has always been sacred. Even when stolen.

When the enslaved were forbidden from gathering in large numbers, they found worship in the fields. Hummed spirituals doubled as escape maps. “Wade in the Water” wasn’t just a song—it was a tactic. A Black hymnbook was a war manual, a coded archive of both grief and getaway.

In the 20th century, when textbooks told us Reconstruction was a disaster and the South just “rose again,” Black communities created parallel systems of truth. Freedom Schools rose from the soil of Mississippi during the 1964 Freedom Summer, where SNCC and CORE volunteers taught Black children not just reading and writing, but dignity. They studied Black history, civil disobedience, and the Constitution that had denied them its promises.

Even now, when governors defund truth, we rewrite it into being. In barbershops, boys are taught about Malcolm and Martin in the rhythm of clippers buzzing against scalp. In hair salons, girls learn about Ida B. Wells in the same breath that teaches them how to wrap their crown. Sunday sermons still hold Audre Lorde under their tongue, even when the preacher doesn’t say her name.

And our artists? Our artists are archivists.

When Beyoncé samples the Black South, when Janelle Monáe queers Afrofuturism, when Kendrick Lamar walks into a Grammy performance in chains—we are reminded that memory is not just in books, it is in the beat. It is in the bone. It is in the body.

Memory, in our hands, becomes improvisation. A poem. A dance. A refusal.

Even the act of loving—deeply, Blackly, queerly—is a kind of rebellion against erasure. Because to be fully seen, and to fully see another, is to carry a memory forward that no policy can kill.

This is our resistance.

It lives in every grandmother’s tale that starts with “Chile, let me tell you.”

It lives in every mural on a crumbling wall that says, “They tried to bury us, but...”

It lives in every lesson a teacher dares to teach, even under threat of losing everything.

This is the archive they can’t touch.

This is the fire they cannot stamp out.

Because we are not waiting for them to return our history to us.

We are the history.

And we are writing new chapters, even now—even here.

Conclusion: The Books They Burn Still Speak

Let me dream with you.

What if, at age eight, every Black child learned about Toussaint Louverture—not just as a footnote in French history, but as the first to crush European slavery with sword and spirit?

What if they knew Bayard Rustin, the gay man behind the March on Washington?

What if they could trace the line from Marsha P. Johnson to George Floyd, from Harriet Tubman to Angela Davis, from Nat Turner to the ballot box?

Imagine classrooms with no lies to correct. Teachers not afraid to teach. Children who look in the mirror and see legacy, not lack.

The children would walk taller. The teachers would speak freer. And the country might finally look itself in the mirror without shattering.

In that America, history would not be a battlefield. It would be a garden.

And we—we would be the bloom.

What they forget, we become.

They burn the books, and still, we rise from the ash, singing the verses by heart. They silence the teachers, and still, we pass the lesson down like an heirloom—braided into hair, tucked into lullabies, carried in the drumbeat of our feet on pavement.

We are not what they think we are: passive, forgetful, compliant. We are the children of fugitives and firemakers. Our history is not just what happened to us—it is what we did in return. Every protest is a page. Every march, a manuscript. Every refusal to die quietly, a footnote in a gospel of survival.

Let them pass their laws. We’ve lived through worse.

Let them erase our names from syllabi. We’ve carved them into stone.

Let them call our knowledge “divisive.” We know that truth always divides the lie from the light.

Somewhere right now, a Black child is reading The Bluest Eye under their covers, flashlight pressed to page like communion. Somewhere, a teacher is slipping a banned poem into the back of a worksheet, knowing that liberation often arrives in whispers. Somewhere, a grandmother is telling the truth in a story that starts with “They don’t teach you this in school, but let me tell you...”

This is the America they cannot kill.

We are what the fire couldn’t swallow.

We are what the curriculum cannot contain.

We are the ones who remember.And every time we tell the story,

every time we refuse to let our ancestors vanish,

every time we say their names with our whole chest—

we win.Let them fear our memory.

Let them tremble at our recall.

Because we remember not only what was done to us—

we remember who we are.And that, beloved, is the most dangerous thing of all.

Annotated Bibliography

1. Snyder, Timothy. On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century. Tim Duggan Books, 2017.

This short yet powerful book provides a warning drawn from historical fascist regimes—particularly Nazi Germany—about how democracies collapse and how propaganda, erasure, and the control of memory are essential tools of authoritarianism. The essay draws on Snyder’s framing of memory as a battleground, particularly in its comparisons between Nazi book burnings and modern American censorship.

2. Whitman, James Q. Hitler’s American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law. Princeton University Press, 2017.

This text offers a deep analysis of how Nazi Germany looked to U.S. race law (e.g., Jim Crow, anti-miscegenation laws) as a blueprint for its Nuremberg Laws. This historical comparison undergirds the essay’s assertion that America’s own legacy of racial suppression influenced regimes abroad.

3. Southern Poverty Law Center. “Hate in the Halls: The Moms for Liberty Movement.” SPLC Report, 2023.

This source provides detailed information about conservative groups like Moms for Liberty that are working to remove books on race, gender, and sexuality from schools. The essay draws from this in the section on coordinated attacks against curriculum.

4. The New York Times. “Florida Rejects African American Studies Class.” The New York Times, Jan. 2023.

This article reports on the Florida Department of Education’s decision to ban AP African American Studies, citing its inclusion of Black queer theory and the Movement for Black Lives. This directly supports the essay’s discussion of Florida’s anti-Black curriculum practices.

5. Anderson, Carol. White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide. Bloomsbury, 2016.

Anderson’s work provides a historical throughline showing how Black advancement is often followed by white backlash—legislative, cultural, and economic. The essay draws from this to position today’s anti-CRT and book banning efforts within a legacy of reactionary suppression.

6. Ladson-Billings, Gloria. “Just What Is Critical Race Theory and What’s It Doing in a Nice Field Like Education?” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, vol. 11, no. 1, 1998, pp. 7–24.

This foundational text on CRT informs the essay’s discussion of why theories of race and systems of power are being attacked in educational settings.

7. bell hooks. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. Routledge, 1994.

hooks’ work is central to the essay’s philosophical thread: that education, particularly Black education, is not neutral but political—and often revolutionary. The essay channels hooks' spirit in its discussion of underground knowledge traditions.

8. Morris, Monique W. Pushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls in Schools. The New Press, 2016.

This book highlights how Black girls are often erased or disciplined within education systems, reinforcing the essay’s point about whose stories are considered legitimate in classrooms.

9. Love, Bettina L. We Want to Do More Than Survive: Abolitionist Teaching and the Pursuit of Educational Freedom. Beacon Press, 2019.

Love’s text directly informs the essay’s theme of resistance through education. It supports the idea that Black educators and communities have always created counter-institutional spaces of learning and joy, even under threat.

10. Taylor, Keeanga-Yamahtta. From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation. Haymarket Books, 2016.

This source is foundational for framing contemporary Black movements like BLM as part of a long genealogy of resistance. It connects directly to the essay’s discussion of modern movements being targeted in curricular bans.

11. PBS. Freedom Summer. Directed by Stanley Nelson, Firelight Media, 2014.

This documentary chronicles the 1964 Freedom Schools established during the civil rights movement, referenced in the essay as historical examples of Black-led educational resistance.

12. Toni Morrison. Burn This Book: PEN Writers Speak Out on the Power of the Word. HarperStudio, 2009.

Morrison’s reflections on censorship and the sacred nature of writing inform the essay’s title and closing. She famously said, “The function of freedom is to free someone else,” a sentiment echoed in the essay’s tone and closing message.

13. American Library Association (ALA). “State of America’s Libraries Report 2023.”

This report tracks book bans across the U.S., noting that books by Black, Indigenous, LGBTQ+, and other marginalized voices are disproportionately targeted. The essay’s claim about library purges and banned authors is substantiated here.