Before The Bricks

Length: • 12 mins

Annotated by Mark Isero

Notes From The Undrowned

A Pride Month Note

The story goes that a brick was thrown, heavy and holy, laced with fury and glitter and grief, and that from its flight, a movement was born. We are told to begin there, at Stonewall, in the summer of 1969. We are told that was the moment queerness finally found its courage, its rebellion, its teeth. We are told that Pride was born in the riot, and that before the riot, there was mostly silence, mostly shame.

But that story is a myth, a convenient one. A myth polished clean for parades and grants, for rainbow-colored capitalism and corporate allyship. A myth that lets white queerness sleep soundly and history books turn quietly.

The greatest lie the devil ever told was that Stonewall was the start.

Not because Stonewall didn’t matter, it did. It was sacred ground – it is sacred ground. But to pretend it was the genesis is to deny the long shadow of what came before. It is to erase the drag queens who ducked nightsticks in D.C. ballrooms in the 1880s. It is to forget the queers who danced through the Harlem Renaissance like it was their only language. It is to silence Black trans women whose lives were a protest long before anyone shouted.

And even Stonewall, as we know it, has been scrubbed raw. We speak Marsha’s name now, pin buttons to denim jackets, raise posters in her image. But we forget she said herself—she didn’t throw the first brick. We made her the symbol because she could not fight us back. We made her the beginning because white queer politics needed a Black martyr more than a Black leader.

History, after all, is not written by the brave. It is written by the survivors of comfort.

"People are trapped in history," Baldwin reminds us, "and history is trapped in them." What is Pride if not a yearly attempt to untrap ourselves, to remember louder, to fight prettier? But even that becomes dangerous when memory is curated, when protest is reduced to performance, and when the truth of our lineage is trimmed to fit the margins of white liberalism.

Before the bricks, there were ballrooms. Before the ballrooms, there were kitchen tables. Before the parades, there were whispered names and chosen kin and holy defiance pressed into breath. And so we begin not at Stonewall, but before it. In the shadows they never wanted to name. In the legacy they could not market. In the fire we kept lit when no one was watching. Because we have always been the riot, and we have always been the beginning.

II.

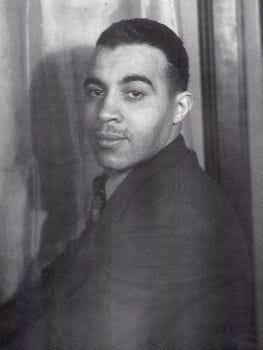

Long before a single brick was lifted at Stonewall, a Black man in a satin gown declared himself Queen.

His name was William Dorsey Swann. Born into slavery in 1860, freed only by war and providence, Swann would become the first known person in the United States to identify as a drag queen. Not as metaphor, not as performance, but as embodied rebellion. In the 1880s and 1890s while the country tried to forget its blood-soaked sins, Swann hosted drag balls in Washington, D.C. These weren’t cabarets for amusement or backroom secrets, they were churches, battlefields, declarations of Black queer sovereignty under siege.

Police raided his gatherings, and newspapers jeered. He was arrested, jailed, and humiliated. And yet, he persisted. In 1896, Swann petitioned President Grover Cleveland for a pardon not for a crime of violence, but for the right to gather, to exist, to celebrate. It was the first documented legal fight for LGBTQ+ rights in this country. Let that be clear: the first legal plea for queer liberation in America came not from the steps of Stonewall, but from a Black drag queen born in bondage. Swann didn’t throw a brick; he wore a crown in a world that told him not to live.

But he was not alone in his audacity. The line stretches forward and backward, braided in breath and broken bones. In the shimmering pulse of the Harlem Renaissance, queerness was not only visible, it was vital. Gladys Bentley, in her tuxedos and piano swagger, tore through cabarets with a voice too holy for straight ears. Richard Bruce Nugent wrote Black queer desire into poetry when such desire was considered sin, sickness, or myth. And inside those moonlit ballrooms where gowns spun like galaxies and chosen families named each other into existence, Black queer people found something rarer than safety: they found each other.

These were not isolated acts of defiance. They were rituals, a sacred choreography of resistance passed hand to trembling hand. Every whisper, every wink, every stitched hem was a refusal to die quietly.

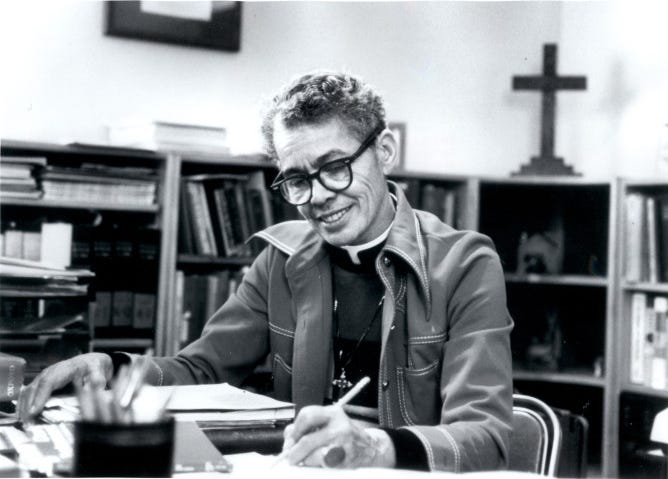

And then there was Bayard Rustin, the architect behind the March on Washington. A Black gay man, pacifist, freedom rider, and deeply spiritual strategist. Though his sexuality was used to silence him publicly, it never severed his conviction. And, Pauli Murray—poet, lawyer, priest, and gender non-conforming visionary coined the phrase “Jane Crow” to describe the double weight of racism and sexism. Pauli lived in the thresholds of gender and language before there were words to hold them.

History does not always reward these names. The destroyers, as Coates reminds us, “will rarely be held accountable. Mostly they will receive pensions.” But even in their erasure, these figures have shaped the marrow of what Pride was supposed to be, a collective breathing space for the disinherited.

So let us not mistake these ancestors for exceptions. They were foundations, ghosts in the framework, saints without feast days. They did not wait for recognition, they danced, they sued the government, they wore tuxedos and gowns, they bled and wrote and loved and built altars out of whatever scraps the world left behind.And we are their echoes. We are their stubborn, surviving breath.

III.

Let us be clear: Stonewall was never just white, it was never just gay, and it was never safe. It was a rebellion sparked by those pushed furthest to the edge—Black and brown trans women, sex workers, street queens, houseless youth, femmes who refused to cower. When the first bottle flew, when fists were raised, when the police were chased down Christopher Street, it was not the well-funded, not the respectable, not the clean-cut gays in three-piece suits who led the charge. It was the dispossessed. Marsha P. Johnson, a Black trans drag queen and sex worker, whose smile could baptize a block. Sylvia Rivera, a Puerto Rican-Venezuelan trans activist who slept in alleyways and still found time to love. Zazu Nova, a Black queen with fists full of heat and defiance. Miss Major, who survived Attica, survived Stonewall, and still wakes up fighting for Black trans girls no one bothers to bury. They weren’t just there. They were the riot.

And yet, within months, even days, the retelling began. The movement that had erupted from the cracks in the street began to be reshaped, reshuffled, rebranded. The rage became rainbow, the radicals became footnotes, and white cis gay men began stepping in front of microphones to tell a story they did not bleed for.

The photograph became the proof. The parade became the product. The protest became palatable. And in the years that followed, the queer movement, once raw and jagged and full of sacred mess, was repackaged for consumption. Rewritten in English only. Presented in suits and slogans that could be digested by the same state that once raided their bars and broke their ribs. This is how movements die, not in the streets, but in the press release.

By the 1980s, the erasure was nearly complete. As AIDS decimated queer communities, especially Black and brown ones, mainstream Pride began to forget the names that had carved its bones. Black queers buried their dead while white queers booked floats. Trans women were disappeared from strategy tables while cis men sold slogans to banks.

And now, over fifty years later, we find ourselves walking past corporate displays and tequila-sponsored drag brunches, wondering what happened to the fire. They hand us rainbow-colored capitalism and dare to call it solidarity. They raise a flag but not bail. They host panels but not funerals.

We died for this, and now they sell it back to us in rainbow glitter and corporate packaged t-shirts.

To honor Stonewall is not to repackage it. To honor Stonewall is to remember it rightly. It is to name who actually threw the first fists, who burned brightest, who got locked in cells and tossed in alleys and spit at even after they helped birth the movement. It is to ask: what does it mean to be lifted as a symbol but abandoned as a human?

Audre Lorde reminded us: “There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle.” Stonewall wasn’t just about queerness. It was about poverty, policing, gender, race, housing, survival. It was about living in a body the state wanted to erase and refusing. It was about standing in front of a loaded gun called America and saying: not today, not again, not without a fight. So we honor them, not by repeating the myth, but by naming the reality: Pride was born not from celebration, but from desperation. Not from visibility, but from vengeance. And if we are to be worthy of it, we must tell the truth — all of it, especially the parts they’d rather we forget.

IV.

In the corners of the city, Black queers gather quietly, fiercely, prayerfully. Sometimes in parks. Sometimes in rented back rooms. Sometimes in homes where the curtains are drawn and the food smells like kin. There’s music, yes, there’s joy —but there is also memory, there is risk, there is grief braided into the laughter like a spine. Because Pride does not mean the same thing to us.

White queerness has often been allowed to assimilate to trade resistance for access, militancy for marketability. And in doing so, it has made Pride into something safe, something purchasable. A day off, a drink special, a rainbow decal on a cop car.

But for us, Black, queer, trans, broke, displaced Pride has never been safe. It has never been just a party. We do not get to forget the funeral just because we are wearing sequins.

Our presence in white-dominated Pride spaces is often conditional, welcomed for optics, rejected in practice. We are stared at, over-policed, hyper-visible when they want to tokenize us, invisible when we demand power. Police stand at Pride not as allies, but as reminders. And even in celebration, we are watched. Profiled, beaten, killed. We are asked to dance with the same boots that crushed our kin.

That is why Black Pride exists, not to divide, but to survive. Because when your laughter is seen as too loud, your body as too much, your gender as too threatening, your joy must be held in rooms that understand it. Rooms where no one will question the scars on your chest or the way you choose to be called, rooms where you are not “included,” but belonged to. Black Pride is not an alternative, it is an altar. Because our joy is not innocent – it is defiant, it is earned, it is paid for in names etched into the air like smoke: Tony McDade. Iyanna Dior. Mesha Caldwell. Dominique Rem’mie Fells. Nina Pop. Breonna. George. Say their names, and feel the room change.

We do not celebrate without remembering. We do not parade without protection. Their freedom is performance, ours is prayer.

Baldwin wrote: “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage almost all the time.” But what he didn’t say, and what we know in our bones is that rage is only half the story, the other half is love. And we carry both. In our music, in our movements, in the way we walk through Pride with our dead on our backs and our heads still lifted because we are still here, still shining, still mourning and most importantly, still holy.

V.

There is a pattern to their violence. It always begins with a name, pronouns misused, a life misdescribed, then comes the law, silence, and then comes the death. And, by the time the obituary is written, the country has already moved on to its next scapegoat.

We are in a moment of orchestrated cruelty. This is not moral panic, it is political strategy in the cruelest sense. This is not culture war — it is war.

Across this country, state after state is introducing legislation to criminalize gender-affirming care, to ban drag performances, to restrict trans youth from accessing education, sports, public bathrooms, air. What began as whispers in conservative corners is now law in over twenty states. They are jailing parents, doxxing doctors, burning books. They are passing bills that pretend to protect children by erasing the very children they claim to care for. Let’s call it what it is: genocidal rhetoric backed by state power.

And though these attacks target many, they fall hardest on Black trans women, who have always been the vanguard of our movements and the first to be forgotten when the credits roll. We owe the very existence of Pride to them, Marsha, Sylvia, Miss Major, and the countless others whose names don’t live in textbooks or documentaries. And now, while white liberalism wrings its hands over language, Black trans women are dying. Disproportionately killed, disproportionately unhoused, disproportionately arrested, surveilled, and shamed.

The country asks, again and again: Why do they need their own spaces? And the answer is: because this one keeps trying to bury them.

To be clear, transphobia is not just a trans issue. It is a gateway drug to authoritarianism. It is the test balloon for how much violence the public will tolerate. And history has shown us when they come for the trans folk, they are preparing to come for all of us. The rollback of trans rights is not the end goal, it is the first domino. Because if you can erase someone's gender, you can erase their citizenship. And if you can erase their body, you can erase their vote, their children, their story, their right to exist. They’re not scared of drag queens reading books. They’re scared of children learning how to recognize themselves. They’re scared of self-determination.

They’re scared of anyone who refuses to be what the empire tells them to be.

Baldwin said, “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read.” And when we read this moment rightly, we see it for what it is: a fire alarm.

And here is the truth the state will not say: When the state writes a law against a name, it is preparing a eulogy.

So what do we do? We protect them; we fund them; we follow their lead; we tell their stories not only in death, but in the wild, radiant complexity of their living. And we remember: if our liberation does not include Black trans women, then it is not liberation, it is a costume. No, it is a bold face fucking lie. They have always been the blueprint.

VI.

We were never meant to make it this far, not in this country, not in these bodies. And yet here we are, not just alive, but alight. Still loving, laughing, dancing on the graves they dug for us.

Black queer life is not a footnote. It is scripture, spellwork, it is survival written in blood and brilliance. I have sat in living rooms thick with incense and Beyonce, wrapped in the arms of queens who taught me how to hold grief and joy in the same breath. We have seen ballroom floors become cathedrals, heels striking tile like liturgy, sequins catching light like stained glass. We’ve watched house mothers pray with their hands, smoothing edges, sewing hems, applying eyeliner like it was anointing oil, these were not parties, they were portals — holy ground dressed in gold lamé and stubborn laughter.

We carry altars inside us. We light candles in each other’s names without waiting for death to make it respectable. We make a family not by blood, but by intention, by who shows up when the world collapses.

I have loved in borrowed rooms. I have danced in basements with no exit signs.

I whispered my name into mirrors and waited for the echo to sound like home. We are the ceremony. We are the burning bush. Every breath we take is a kind of resistance. Every kiss a kind of prayer. To be Black and queer and alive is not a coincidence, it is choreography, it is covenant, it is creation. A conjuring of self from the ash of what this world tried to erase. And this is why Pride must return to the sacred. Not the branded, not the performative. But the deeply personal, the spiritual, the survivalist.

Pride is not an event. It is a remembering, a recommitment, a rite. It is the ballroom floor, the kitchen table, the back pew of the church you were told to leave. It is the way we call each other “baby” and “beloved” and “girl” like gospel. It is the silence after a name is said and the room goes still because we all know what it cost them to be here.

Pride is not a parade—it is a procession, it is not a flag, it is a flame. It is not a brand—it is a blessing.

Baldwin wrote, “Love takes off the masks that we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within.” And we? We have been removing masks for generations. We have worn too many for too long. So this is the invitation: return to the sacred. Not the safe, not the sanctioned, but the trembling holy space of truth.

To be Black and queer and still breathing is a miracle. And every miracle deserves its altar.