Why Apple Still Hasn’t Cracked AI

Length: • 22 mins

Annotated by Mats Staugaard

Illustration: Ariel Davis for Bloomberg Businessweek

Back in 2018 it looked like Apple Inc.’s artificial intelligence efforts were finally getting on track. Early that year, Craig Federighi, Apple’s software chief, gathered his senior staff and announced a blockbuster hire: The company had just poached John Giannandrea from Google to be its head of AI. JG, as he’s known in the industry, had been running Google’s search and AI groups. Under his leadership, teams were deploying cutting-edge AI technology in Photos, Translate and Gmail—work that, along with the 2014 acquisition of the pioneering British company DeepMind, had given Google a reputation as a leader in AI.

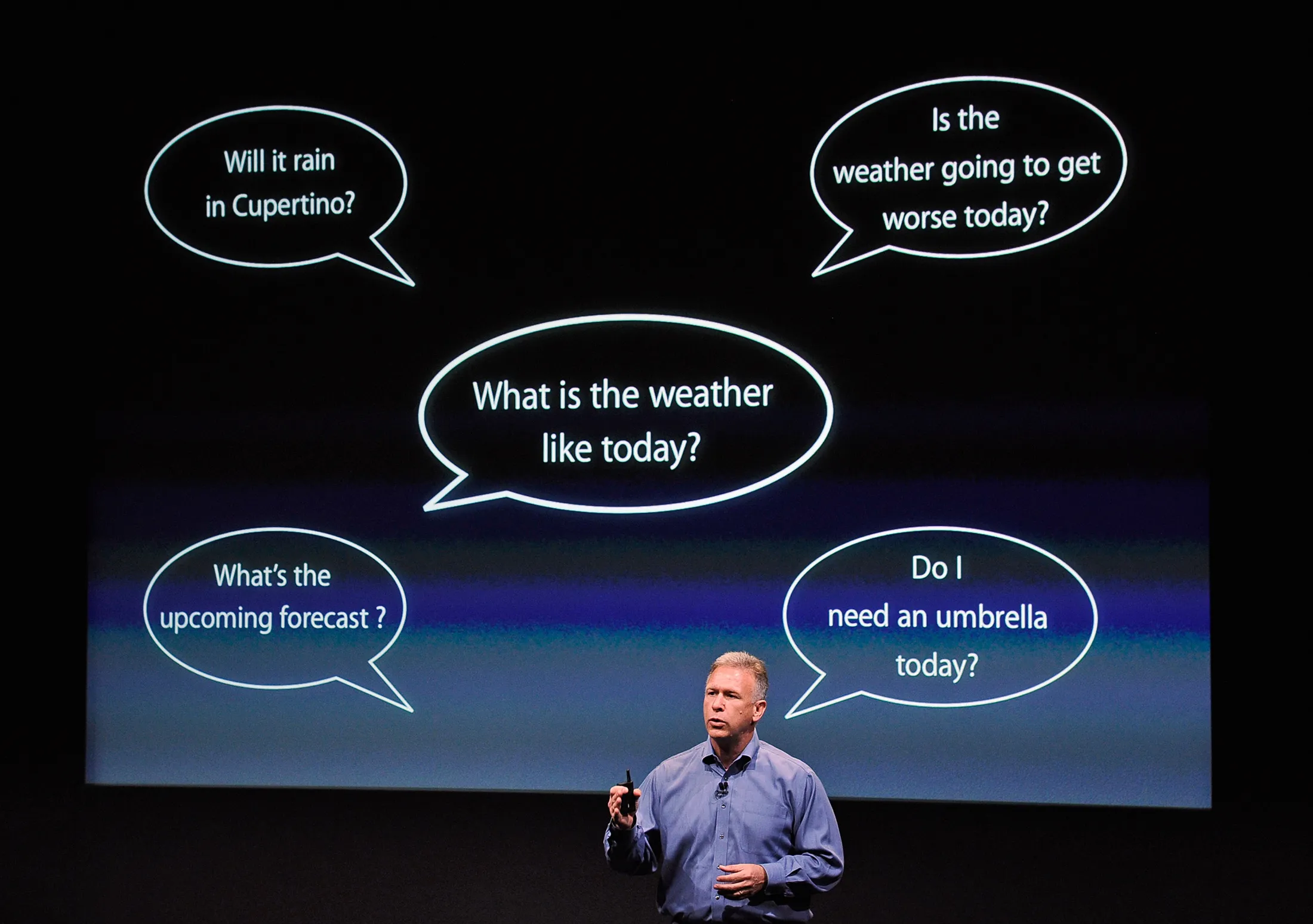

To Apple’s leadership, the Giannandrea hire wasn’t just a coup at the expense of their fiercest rival. It was also, they hoped, the start of the company’s transformation into an AI powerhouse. Just before the death of co-founder Steve Jobs in 2011, Apple had unveiled its voice assistant, Siri. At first, Siri felt like something out of science fiction—once again, Apple had taken a futuristic computing concept and turned it into a mainstream product. But within a few years, Google, Amazon.com Inc. and other competitors had introduced voice assistants that felt far more advanced, while Apple’s struggled with basic comprehension and commands.

The Scottish-born Giannandrea would oversee a group that united all of Apple’s AI work. Several employees say top executives had long believed the company’s challenges traced in part to the disaggregated nature of Apple’s AI efforts, which were divided among a slew of different product development teams. (The employees, like others interviewed for this article, requested anonymity to discuss sensitive matters.) Now, machine learning research, testing operations and Siri would be under one umbrella. Giannandrea would report directly to Chief Executive Officer Tim Cook, giving AI the same prominence as software, hardware and services, the main groups that make up Apple’s workforce.

Some content could not be imported from the original document. View content ↗

Follow The Big Take daily podcast wherever you listen.

Federighi’s excitement in announcing the hire was palpable—Siri had been handed off multiple times since its launch, ending up with him, and now he was passing it off to Giannandrea. “This is exactly the kind of person we needed for AI,” he told his staff. In addition to Giannandrea’s work at Google, where many considered him the most powerful executive except the CEO, he’d been chief technology officer of internet pioneer Netscape. “Who else in the world would you get?” asks someone involved in the hire.

Seven years after Giannandrea arrived, the optimism he brought with him is gone. Apple’s AI has only fallen further behind. Since OpenAI’s ChatGPT software burst into public consciousness in 2022, every major tech company has accelerated its efforts to develop the large language models (LLMs) that power such programs, incorporate them into voice assistants and other tools, and hype them to consumers.

Apple, like its competitors, has rolled out new AI features, but they’ve mostly been notable for being delayed and underwhelming. Last June, at its Worldwide Developers Conference (WWDC), the company announced Apple Intelligence, calling it “AI for the rest of us”—a nod to the original Mac desktop, first marketed in 1984 as “the computer for the rest of us.” Promised features included new tools for improving writing, summarizing emails and notifications, as well as for generating custom emoji and images from written descriptions. The company also previewed an AI-driven revamp of Siri. For the first time, Apple said, the voice assistant would be able to delve into a user’s personal data and on-screen content to answer queries. To demonstrate, a top Giannandrea deputy asked Siri about her mom’s travel plans. The answer drew seamlessly on information from emails and text messages to help construct an itinerary. Apple said users would also be able to control their devices in new ways through Siri: choosing, cropping and emailing photos to family members, for example, without touching the screen.

The prospect of truly AI-powered devices led Apple’s share price to rise sharply. The buzz grew in September, when the company announced that its newest phone, the iPhone 16, had been “built from the ground up” for Apple Intelligence. But when the device went on sale that month, it didn’t have the AI features—the first of them, including the writing tools and summaries, didn’t come out for another month and a half. The custom “Genmojis” didn’t arrive until December. A major upgrade to the iOS notifications feature that would prioritize alerts based on urgency rolled out only in March.

As for the Siri upgrade, Apple was targeting April 2025, according to people working on the technology. But when Federighi started running a beta of the iOS version, 18.4, on his own phone weeks before the operating system’s planned release, he was shocked to find that many of the features Apple had been touting—including pulling up a driver’s license number with a voice search—didn’t actually work, according to multiple executives with knowledge of the matter. (The WWDC demos were videos of an early prototype, portraying what the company thought the system would be able to consistently achieve.) The planned rollout was delayed until May and then indefinitely, even as the features were still being promoted on commercials for the iPhone 16. Some customers who’d bought what they thought would be AI-enabled devices joined class-action lawsuits accusing Apple of false advertising. The company declined to comment on the lawsuits. It also declined to comment for this story, including on behalf of the executives mentioned.

The new Siri won’t be out in time for next month’s WWDC, a year after the upgrade was first announced. Instead of getting an overhauled assistant—let alone a full-fledged ChatGPT competitor, as many rivals have released—users will have to be satisfied with promises of further Apple Intelligence deployment. There will also be various non-AI software upgrades, such as a redesigned user interface that makes the iPad, Mac and iPhone operating systems more cohesive and reminiscent of the software that runs the company’s mixed-reality headset, the Vision Pro.

“This is a crisis,” says a senior member of Apple’s AI team. A different team member compares the effort to a foundering ship: “It’s been sinking for a long time.” According to internal data described to Bloomberg Businessweek, the company’s technology remains years behind the competition’s.

Being late to a potentially world-changing advance isn’t necessarily catastrophic for Apple. The company is often content to wait for competitors to pioneer new tech, with all the risks that entails, before releasing its own well-designed, highly accessible version to its billion-plus customers. It’s done this with MP3 players, smartphones, tablets, watches and earbuds. Asked on Apple’s quarterly earnings call this May about all the delays, Cook pointed to the Apple Intelligence features that have made it to market, as well as its expansion to Spanish, Chinese and other languages. The Siri upgrade, he said, simply needed more time to meet Apple’s quality standards. “There’s not a lot of other reason for it,” Cook said. “It’s just taking a bit longer than we thought.”

What’s notable about artificial intelligence is that Apple has devoted considerable resources to the technology and has little to show for it. The company has long had far fewer AI-focused employees than its competitors, according to executives at Apple and elsewhere. It’s also acquired fewer of the pricey graphics processing units (GPUs) necessary to train and run LLMs than competitors have. Its leadership has undergone a significant shake-up this year, in response to these and other issues, with Siri and other AI-related teams removed from Giannandrea’s command.

But while some employees attribute the struggles to decisions made by particular executives, others see symptoms of a deeper problem. Apple became the world’s most valuable tech company by methodically releasing exquisite products with handpicked content, running on software that’s updated meaningfully only once a year; AI is proving to be a faster, messier and more intrusive business. And historically, Apple’s most successful products have depended on core technologies developed in-house—multitouch for the iPhone and advanced chips for iPads and newer Macs, to take two examples. With AI this formula hasn’t come together. The company killed its self-driving car project last year, after spending billions of dollars on it across a decade, in part because it realized its AI wouldn’t be able to deliver on the promise of a fully autonomous vehicle. Continued failure on AI would likely doom many of Apple’s plans for the future, from augmented-reality glasses and robots to watches and earbuds that can recognize objects in the world around them. And it would leave Apple at a grave disadvantage in the battle over how users will interact with smart devices in the coming years.

Eddy Cue, Apple’s senior vice president for services and a close confidant of Cook’s, has told colleagues that the company’s position atop the tech world is at risk. He’s pointed out that Apple isn’t like Exxon Mobil Corp., supplying a commodity the world will continue to need, and he’s expressed worries that AI could do to Apple what the iPhone did to Nokia. In a federal court appearance this month related to the Justice Department’s lawsuit against Alphabet Inc., Cue said the iPhone might be irrelevant within a decade—“as crazy as that sounds.”

Steve Jobs wasn’t particularly interested in building search engines, intelligent or otherwise. “Steve just didn’t believe in customers going to try to find things,” says someone who worked with him. “He believed that Apple’s job was to curate and show customers what they should want.” That belief, like many of Jobs’, shaped the company long after his death. In the mid-2010s, Apple explored the idea of placing a search bar at the top of the iPhone’s home screen, rather than burying it behind a swipe gesture. But Apple’s design team vetoed the idea.

Still, when Jobs first encountered Siri—originally an offering in Apple’s App Store—he was hooked. The app’s co-creator, Dag Kittlaus, says the original concept was for a “do engine.” “The ultimate vision was that you could talk to the internet and your assistant would just handle everything for you,” he recalls. “You wouldn’t even need to know where that information would need to come from, and the whole app and website discovery problem would be taken out of the equation.”

In its early form as an iPhone app, Siri was capable of making dinner reservations, finding a movie theater or calling a taxi. Jobs immediately saw it as far more than a mere app—he believed it could potentially become the primary user interface for Apple’s devices. Soon after he started using Siri, he phoned Kittlaus and invited him and his co-founders over to his house. During a three-hour chat, Jobs offered to buy their company. When Kittlaus balked, Jobs proceeded to call him 24 days in a row.

After Kittlaus finally relented, Jobs turned Siri into one of Apple’s top development priorities. “He made it his personal project,” Kittlaus remembers. “I met with him every week until he no longer could for health reasons.”

Siri was released just after Jobs died. Development in its first years concentrated mainly on basic tasks such as providing weather info, setting timers, playing music and handling texts. It didn’t benefit heavily from Apple’s nascent machine learning research, which focused on applications including facial and fingerprint recognition, smart suggestions (like telling you when you should leave for an appointment, on the basis of traffic), improved maps and the company’s moon shots at the time: the headset and the car.

Some of the most senior executives overseeing software engineering thought Apple should be making AI more prominent in the iPhone’s operating system. Around 2014 “we quickly became convinced this was something revolutionary and much more powerful than we first understood,” one of them says. But the executive says they couldn’t convince Federighi, their boss, that AI should be taken seriously: “A lot of it fell on deaf ears.”

Apple did start acquiring dozens of smaller AI businesses to support its efforts, including machine learning companies Laserlike, Tuplejump and Turi. It even considered buying Mobileye Global Inc. at a proposed price of around $4 billion, according to people familiar with the talks. The deal, which would have been Apple’s biggest-ever acquisition, promised to speed development of Apple’s autonomous driving systems and computer vision technologies, and it would have added AI talent that could buttress other projects. But ultimately, Apple passed, and Intel Corp. went on to buy Mobileye in 2017 for $15 billion.

Apple’s car project did yield one early AI success: a specialized component, the Apple Neural Engine, that allowed its chips to handle the vast amount of AI processing needed for autonomous driving. Chips with the neural engine would later become standardized across the iPhone, iPad and other hardware, giving the company’s devices the capability to run generative AI models.

Cook, who was generally known for keeping his distance from product development, was pushing hard for a more serious AI effort. “Tim was one of Apple’s biggest believers in AI,” says a person who worked with him. “He was constantly frustrated that Siri lagged behind Alexa,” and that the company didn’t yet have a foothold in the home like Amazon’s Echo smart speaker.

When Giannandrea started at Apple in 2018, fellow executives say, he described its closed software ecosystem as an intriguing advantage, letting it instantly deploy new features to billions of devices. Almost immediately, though, he concluded the company would need to spend hundreds of millions of dollars more on the kinds of large-scale testing and image and text annotation required to train the machine learning models that AI technologies are built on. He got enough money to hire some top AI researchers away from Google and to expand the teams responsible for testing and data analysis.

Giannandrea also took aim at Siri, removing its leader and proposing to kill rarely used features, which he told colleagues would reduce the amount of code Siri required and keep the team focused on its most important functions. He was skeptical of the car, a project he’d briefly be put in charge of. (When Apple later gave up on it, hundreds of the AI engineers who’d been working on it were folded back into his group.)

Still, Giannandrea’s efforts were often stymied. Federighi, Apple’s software chief, remained reluctant to make large investments in AI—he didn’t see it as a core capability for personal computers or mobile devices and didn’t want to siphon resources away from developing annual updates to the iPhone, Mac and iPad operating systems, according to several colleagues. “Craig is just not the kind of guy who says, ‘Hey, we need to do this big thing that will require big budgets and a ton more people,’” a longtime Apple executive says.

Other leaders shared Federighi’s reservations. “In the world of AI, you really don’t know what the product is until you’ve done the investment,” another longtime executive says. “That’s not how Apple is wired. Apple sits down to build a product knowing what the endgame is.”

As a result, the company was blindsided by ChatGPT’s launch in November 2022. One senior executive says Apple Intelligence “wasn’t even an idea” before that. “It’s not like what OpenAI was doing was a secret,” says another. “Anyone who was paying attention to the market there should have seen it and jumped all over it.”

Within a month of ChatGPT’s release, Federighi used generative AI to write code for a personal software project he was working on, according to people familiar with the events. The technology’s potential was suddenly evident to him. He, Giannandrea and other executives began meeting with OpenAI, Anthropic and other players to get a crash course in the latest models and the market. Federighi came away demanding that Apple’s scheduled 2024 iPhone operating system release, iOS 18, have as many AI-powered features as possible. Giannandrea assembled a team to ramp up work on LLMs to support those features—something its competitors had done years earlier.

As Apple worked toward Intelligence’s big June debut at WWDC 2024, it had to come to terms with how far behind its generative AI capabilities were. It could manage basic image creation and had a chatbot it was testing internally, but the bot lagged significantly behind ChatGPT—according to company data described to Businessweek, the competing product was at least 25% more accurate at fulfilling most types of queries.

The need to offer a version of the one AI product consumers really seemed to want set off a scramble to strike a partnership. The company started talking with competitors including Google, Anthropic and OpenAI about integrating their technology into Apple’s software. Giannandrea lobbied hard for Apple to go with Google’s Gemini—arguing, according to colleagues, that OpenAI doesn’t have staying power and isn’t trustworthy or protective of personal data. Apple’s corporate development team concluded otherwise, however, and at WWDC the company announced it would be routing requests that Siri itself couldn’t handle to ChatGPT.

The integration didn’t become a reality until December, but once it did, it was one of the few Intelligence features that worked as advertised. There were successful releases, including email summaries, which replace the preview line in your inbox with a synthesized version of the message, and Writing Tools, which can edit, reorganize and summarize prose. (The text composition AI for Writing Tools, though, was ChatGPT’s.) But other features seemed to many users as though they’d been rushed to market, even as they came out months behind schedule. The Genmojis, which let people conceive custom emoji—say, a peacock merged with a popsicle—rarely looked like the slick graphics Apple touted in TV ads and on billboards in major cities, and they required so much processing power they could overheat iPhones and eat into battery life. The news summaries feature was shut down after some of its AI-generated headlines proved embarrassingly false, including one claiming that alleged killer Luigi Mangione had shot himself. Some of the more computation-heavy AI features only worked because Apple’s online services division had fortuitously conceived a cloud server project that could handle anything the phone couldn’t.

Apple’s Siri plans were even further behind. The company had been promoting the assistant’s new features in TV ads since the iPhone 16 launch, despite their being nowhere near ready. In one spot, Bella Ramsey, star of HBO’s The Last of Us, sees a man at a party, draws a blank on his name and quickly pulls out an iPhone. “What’s the name of the guy I had a meeting with a couple of months ago at Café Grenelle?” Ramsey asks. Siri comes back with the name in the time it takes “Zac” to walk across the room.

The lack of a homegrown AI chatbot worried some Apple executives more than others. According to several employees, Giannandrea has argued internally that AI agents are still many years away from replacing humans in a meaningful way, and that most consumers share his distrust of generative artificial intelligence. The employees say that accounts for why he didn’t fight to build a true ChatGPT competitor of his own for consumers. Colleagues say Giannandrea has told them that consumers don’t want tools like ChatGPT and that one of the most common requests from customers is to disable it.

In March 2025, Apple confirmed a Bloomberg News report that the new Siri would be postponed. It pulled the Ramsey ads from YouTube and major television networks. The following week, the Siri team’s then-boss, Senior Director Robby Walker, met with his demoralized workers for a kind of pep talk. “We swam hundreds of miles—we set a Guinness Book of World Records for swimming distance—but we still didn’t swim to Hawaii,” he said, according to people familiar with the meeting. “And we were being jumped on, not for the amazing swimming that we did, but the fact that we didn’t get to the destination.” For all its efforts, the team was still at sea.

Walker told everyone at the meeting to develop the upgrades for the next version of the iPhone operating system, iOS 19, due in September. But he also told them he wasn’t sure when the upgrades, which didn’t work properly a third of the time, would actually be released, in part because other features were a higher priority. “These are not quite ready to go to the general public, even though our competitors might have launched them in this state or worse,” he said.

Members of the Siri group say Walker’s assessment actually understated the problems. “There are hundreds of bugs right now,” one says. “It’s whack-a-mole. You fix one issue, and three more crop up.”

The main technical issue is that Apple essentially had to split Siri’s infrastructure in half, with the old code underpinning legacy features such as setting alarms and the new code underpinning requests that draw on personal data. The kludge was considered necessary to bring the new features to market as soon as possible, but it backfired, creating integration issues that led to delays. Individual features might look good, employees say, but when code is merged so the pieces can be tested together in Siri, things begin to fall apart.

With the project flagging, morale on the engineering team has been low. “We’re not even being told what’s happening or why,” one member says. “There’s no leadership.”

Inside Apple, Giannandrea has absorbed much of the blame for the delays and false starts, according to several employees and people close to the company. They say he’s found it difficult to fit in with the members of Apple’s innermost circle, who’ve worked together for decades and run the company like a family business. And he’s learned, like senior transplants before him, that this makes it difficult to enact change. Apple’s leadership is a realm of forceful personalities who are ultimately judged on bringing new products to market. Giannandrea is low-key, and some people say he didn’t fight hard enough to get the money his group needed. “JG should have been much, much more aggressive in getting funding to go big. But John’s not a salesman. He’s a technologist,” says an employee who knows him.

Others say Giannandrea isn’t hands-on enough and doesn’t drive his workers particularly hard. “Every other team at Apple, at least in engineering, is balls-to-the-wall, get it out, get it out on time, and JG’s team just doesn’t operate that way,” one executive says. “They just don’t execute.” The perception of coddling extended to perks, as well. Unlike at other Silicon Valley giants, employees at Apple headquarters have to pay for meals at the cafeteria. But as Giannandrea’s engineers raced to get Apple Intelligence out, some were often given vouchers to eat for free, breeding resentment among other teams. “I know it sounds stupid, but Apple does not do free food,” one employee says. “They shipped a year after everyone else and still got free lunch.”

Giannandrea’s purported lack of urgency may be as much philosophical as temperamental, though. Conservative about the pace of AI development and skeptical about the value of chatbots, he’s argued internally that there’s little urgent threat from OpenAI, Meta, Google and the rest. Instead, colleagues say, Giannandrea maintains that what users want in an assistant is an interface for controlling devices. Despite the delays and setbacks, he still holds to that vision.

Failure, of course, is an orphan, and it’s simplistic to see the missteps as one person’s fault. For his part, Giannandrea has told colleagues that much of the blame should be on Apple’s marketing and advertising teams—which Greg Joswiak and Tor Mhyren oversee different aspects of—for hyping unfinished features. Product managers are responsible for being straightforward with marketing about when things will actually be ready. Federighi is the ultimate decision-maker for software. And Cook sets the entire company’s product development culture.

Former Chief Financial Officer Luca Maestri’s conservative stance on buying GPUs, the specialized circuits essential to AI, hasn’t aged well either. Under Cook, Apple has used its market dominance and cash hoard to shape global supply chains for everything from semiconductors to the glass for smartphone screens. But demand for GPUs ended up overwhelming supply, and the company’s decision to buy them slowly—which was in line with its usual practice for emerging technologies it isn’t fully sold on—ended up backfiring. Apple watched as rivals such as Amazon and Microsoft Corp. bought much of the world’s supply. Fewer GPUs meant Apple’s AI models were trained all the more slowly. “You can’t magically summon up more GPUs when the competitors have already snapped them all up,” says someone on the AI team.

Read more: How the AI Boom Created the Most Valuable Monopolies in History

Apple’s long-standing commitment to user privacy also hindered it. The company’s base of 2.35 billion active devices gives it access to more data—web searches, personal interests, communications and more—than many of its competitors. But Apple is much stricter than Google, Meta and OpenAI about allowing its AI researchers access to customer data. Its commitment to privacy also extends to the personal data of noncustomers: Applebot, the web crawler that scrapes data for Siri, Spotlight and other Apple search features, allows websites to easily opt out of letting their data be used to improve Apple Intelligence. Many have done just that.

All this has left Apple’s researchers more heavily reliant on datasets it licenses from third parties and on so-called synthetic data—artificial data created expressly to train AI. “There are a thousand noes for everything in this area, and you have to fight through the privacy police to get anything done,” says a person familiar with Apple’s AI and software development work. An executive who takes a similar view says, “Look at Grok from X—they’re going to keep getting better because they have all the X data. What’s Apple going to train on?”

It’s another example of how AI is proving to be a technology that doesn’t play to Apple’s strengths. “The usual playbook,” a longtime executive says, “is we’re late, we have over a billion users, we’re going to grind it out, and we’re going to beat everyone. But this strategy isn’t going to work this time.”

As Apple tries once again to rescue its AI operations, it’s facing some unique external challenges. To meet expected European Union regulations, the company is now working on changing its operating systems so that, for the first time, users can switch from Siri as their default voice assistant to third-party options, according to a person with knowledge of the matter. Barring a major leap with Apple’s products, many users may make that switch. In addition to products from OpenAI, Anthropic, Meta and Alphabet, others from innovative startups like DeepSeek continue to crop up.

Employees say Apple now has its AI offices in Zurich creating a new software architecture to replace the problematic Siri hybrid—a so-called monolithic model, entirely built on an LLM-based engine, that would eventually make Siri more believably conversational and better at synthesizing information. (The secret project is called, unsurprisingly, LLM Siri.) The company has thousands of analysts in offices from Texas to Spain to Ireland reviewing Apple Intelligence summaries for accuracy, comparing its output against the source material to determine how often the system is producing the distorted responses known as AI hallucinations. Thanks to a recent software update, iPhones have also been enlisted to help improve Apple’s synthetic data. The fake data is assessed and enhanced by comparing it with the language in user emails on their phones, providing real-world reference points for AI training without feeding actual user information into the models.

This spring, Giannandrea was stripped of all control over product development, including the programs for Siri engineering and future robotics devices. That came after Cook lost faith in his ability to execute the creation of new products, according to fellow executives. Siri is now headed by Mike Rockwell, who led the team that created the Vision Pro mixed-reality headset. Rockwell reports to Federighi, who’s taken on more responsibility for Apple’s AI software-related product road map. Giannandrea’s product managers have been moved under Federighi’s oversight, while Rockwell has revamped the Siri management team by putting his top lieutenants from the headset project in charge. Walker, who’d been running Siri under Giannandrea, lost most of his engineers and was assigned to a new project.

Giannandrea retains oversight of AI research, the development and improvement of large language models, the AI analysts, and some infrastructure teams. Insiders say that some Apple executives have discussed the idea of shrinking Giannandrea’s role still further or of him being put on a path to retirement (he’s 60), but that Federighi and others have concerns that if he leaves, the prized researchers and engineers he brought in would follow him out the door.

At least for now, Giannandrea is staying on, telling colleagues he doesn’t want to leave before the company’s AI work is in proper shape. He’s also professed to them that he’s relieved Siri is now someone else’s problem.

That someone, Rockwell, was initially reluctant to take a job reporting to Federighi, given Federighi’s past AI skepticism, according to multiple colleagues. On the other hand, it was an opportunity to revamp a feature that Rockwell has complained about for years. When he joined Apple in 2015, he proposed that Siri be much more capable and central to the user experience: a sort of always-on life co-pilot. “He would rant about how important Siri is and how it will be the most important way people will interact with their phone,” someone who knows Rockwell says. At the time, Rockwell succeeded mainly in getting the company to upgrade the assistant’s voices by hiring expensive actors and opening high-end recording studios. When he started the headset project, he initially wanted Siri to be a core navigation interface, but he struggled to get the Siri group on board. He’ll now be better positioned to push for the resources necessary to create an assistant that works like ChatGPT’s well-received voice mode. Already, Rockwell is reorganizing the team to focus on improving the voice assistant’s speed and comprehension.

Meanwhile, Apple, like other tech giants, is noting the ways user habits are changing. Google searches on Apple devices fell last month. “That has never happened in 22 years,” Cue said in his court testimony, citing AI as the reason. To that end, he said, the company is looking at deals with the likes of OpenAI and Anthropic as possible search replacements in the Safari web browser—an acknowledgment that users are increasingly using LLM-based assistants to find information. Google Gemini, the service Giannandrea wanted to add to Siri last year, is on track to be added in iOS 19 as a ChatGPT alternative, according to people with knowledge of the plan. Apple is also in preliminary talks with the startup Perplexity to eventually become a ChatGPT alternative in Siri and an AI search engine provider in Safari, according to other people with knowledge of the matter.

As for Apple’s homegrown chatbot efforts, some executives are now pushing, despite Giannandrea’s prior reluctance, to turn Siri into a true ChatGPT competitor. To that end, the company has started discussing the idea of giving the assistant the ability to tap into the open web to grab and synthesize data from multiple sources. According to employees, the chatbot the company has been testing internally has made significant strides over the past six months, to the point that some executives see it as on par with recent versions of ChatGPT. An Apple chatbot, integrated into Siri, would help hedge against the potential loss of the $20 billion a year that Alphabet pays for Google to be the default search engine in Safari—a deal US antitrust regulators have been targeting. Apple’s leadership is also optimistic about another of its delayed AI features, one that would allow Siri to integrate with iPhone apps, letting users more deeply control their devices with their voice. This would help the lucrative App Store—also a $20 billion annual business—continue to coexist with chatbots, which might otherwise supplant apps entirely.

Sources at Apple say that, for the next version of iOS, slated for introduction at WWDC 2025 in June, the company plans to focus on upgrading existing Apple Intelligence capabilities and adding some new ones, such as an AI-optimized battery management mode and a virtual health coach. Significant upgrades to Siri—including the ones promised nearly a year ago—are unlikely to be discussed much and are still months away from shipping. The Apple sources say the company, despite its hopes for LLM Siri, is also preparing to separate the Apple Intelligence brand from Siri in its marketing. It’s a tacit admission that the voice assistant’s poor reputation isn’t helping the company’s AI messaging. Another change: Apple, for the most part, will stop announcing features more than a few months before their official launch.

The AI-powered Siri does have an optimist in Kittlaus, the original app’s co-founder. “All of the foundational model companies have no idea what an assistant is, while Apple has been working on the concept since 2010,” he says. All the company needs to do, he argues, is make Siri much, much smarter. “They still have the button, the brand and, if they do a brain transplant for Siri, they have every opportunity to take over as the assistant of choice.”

Read next: Microsoft’s CEO on How AI Will Remake Every Company, Including His