Europe Is Getting Ready for the End of NATO

Length: • 5 mins

Annotated by 🕋 John Philpin

Can Europe get it together?

/Photographer: Justin Tallis/Getty Images

This is a column I never dreamed I’d be writing, as a former supreme allied commander of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. But sadly, given all the skeptical and increasingly divisive rhetoric about the venerable alliance emanating from Washington and Europe in the early days of the second Donald Trump administration, it is time to think about what the world would look like geopolitically if the US pulled out.

Are we indeed in the last days of NATO? What would replace it, if anything? Or, if it survived, what would NATO look like without the US?

Pulling America out of NATO would be a mistake of epic proportions — but there are influential politicians in the Republican Party who are seriously advocating doing so, or at least musing about the possibility. As Senator Markwayne Mullin of Oklahoma said recently: “NATO has not always been playing in our best interest. And when it’s not America’s best interest anymore, we should relook at things.” Last June, 46 House Republicans voted for an amendment defunding NATO.

Vice President JD Vance was scornful about the alliance in his scathing speech at the Munich Security Conference last month. And of course, last week’s surreal public shouting match in the Oval Office between Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy, catalyzed by Vance, doesn’t inspire much confidence in future NATO cooperation.

The decision by the US to vote against a UN resolution condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, joining with Russia and North Korea, was a shocking demonstration of the transatlantic alliance’s failing cohesion.

On the European side, doubt about the US commitment is increasing. French President Emmanuel Macron has been talking about the need for independent European defense forces — “strategic autonomy” — for years. He and UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer held an emergency meeting of European leaders over the weekend to discuss a separate initiative to end the war in Ukraine.

Germany’s chancellor-in-waiting, Frederick Merz, has been equally blunt. “We must prepare for the possibility that Donald Trump will no longer uphold NATO’s mutual defense commitment unconditionally," Merz told a German broadcaster. “It is crucial that Europeans make the greatest possible efforts to ensure that we are at least capable of defending the European continent on our own.”

And there was Zelenskiy’s understandable call for a “united European military,” code for “we can’t count on the US anymore,” something he was pushing even before the tongue-lashing he received from Trump last week.

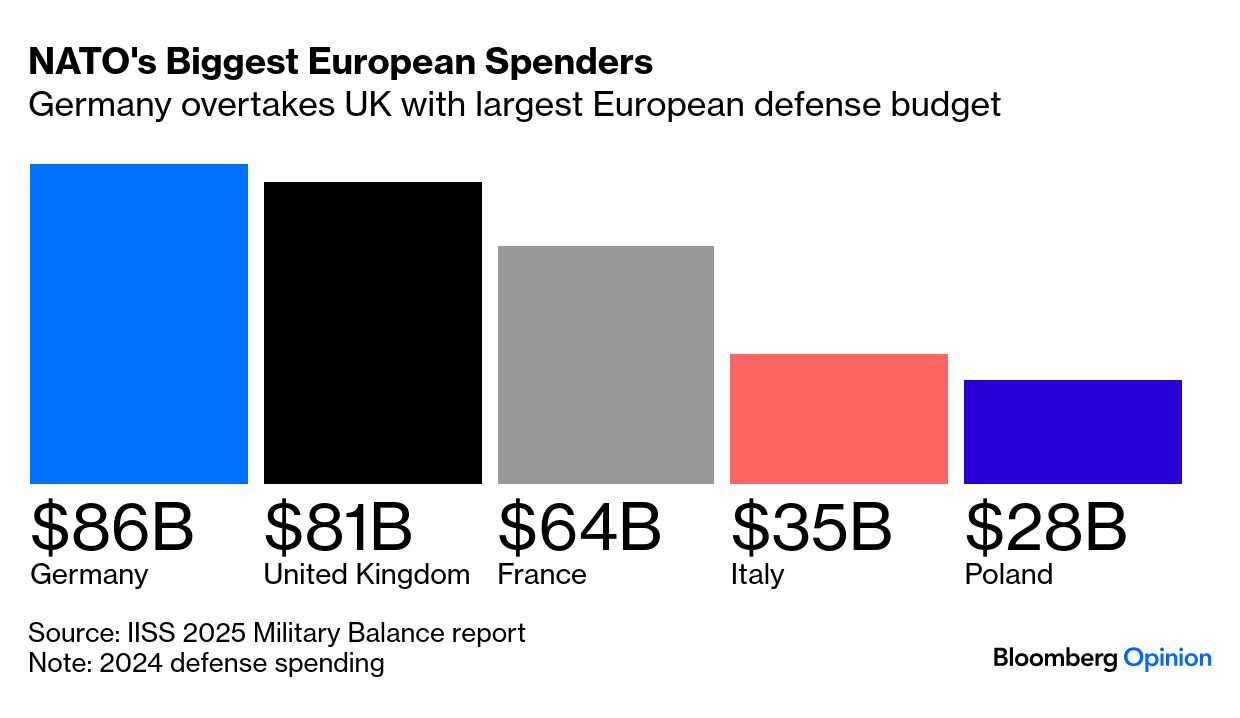

Yet despite all the rhetoric, the value proposition of NATO to the US remains high. Overall defense spending by Europe, spurred by the threat of Russia’s aggression and Trump’s pressure, is finally hitting the alliance goal of 2% of GDP. NATO is seriously discussing increasing that to at least 3.5%, the level of spending by the US.

Collectively, Europe has the second largest defense budget in the world, bigger than either China or Russia. Large, capable defense companies in Europe — Airbus SE, BAE Systems PLC, Saab AB, Thales SA, Naval Group SA, Rolls-Royce PLC, Rheinmetall AG, Fincantieri SpA and others — produce immense amounts of high-quality equipment. They are going to be ramping up and receiving huge contracts — largely at the expense of US defense firms and workers.

And for all our frustration with the Europeans, the US will ultimately want them to help us face the ever-increasing Chinese threat in the Pacific. Their contributions in cybersecurity, intelligence and space operations are key; and they are crucial for Arctic operations, where six of the nations facing Russia across the North Pole are NATO members.

Above all, of course, the European allies share our fundamental values of democracy, liberty and human rights. They fought and died alongside us in Afghanistan, and deployed under my command to Libya, the Balkans, Iraq, and on counterpiracy operations off East Africa.

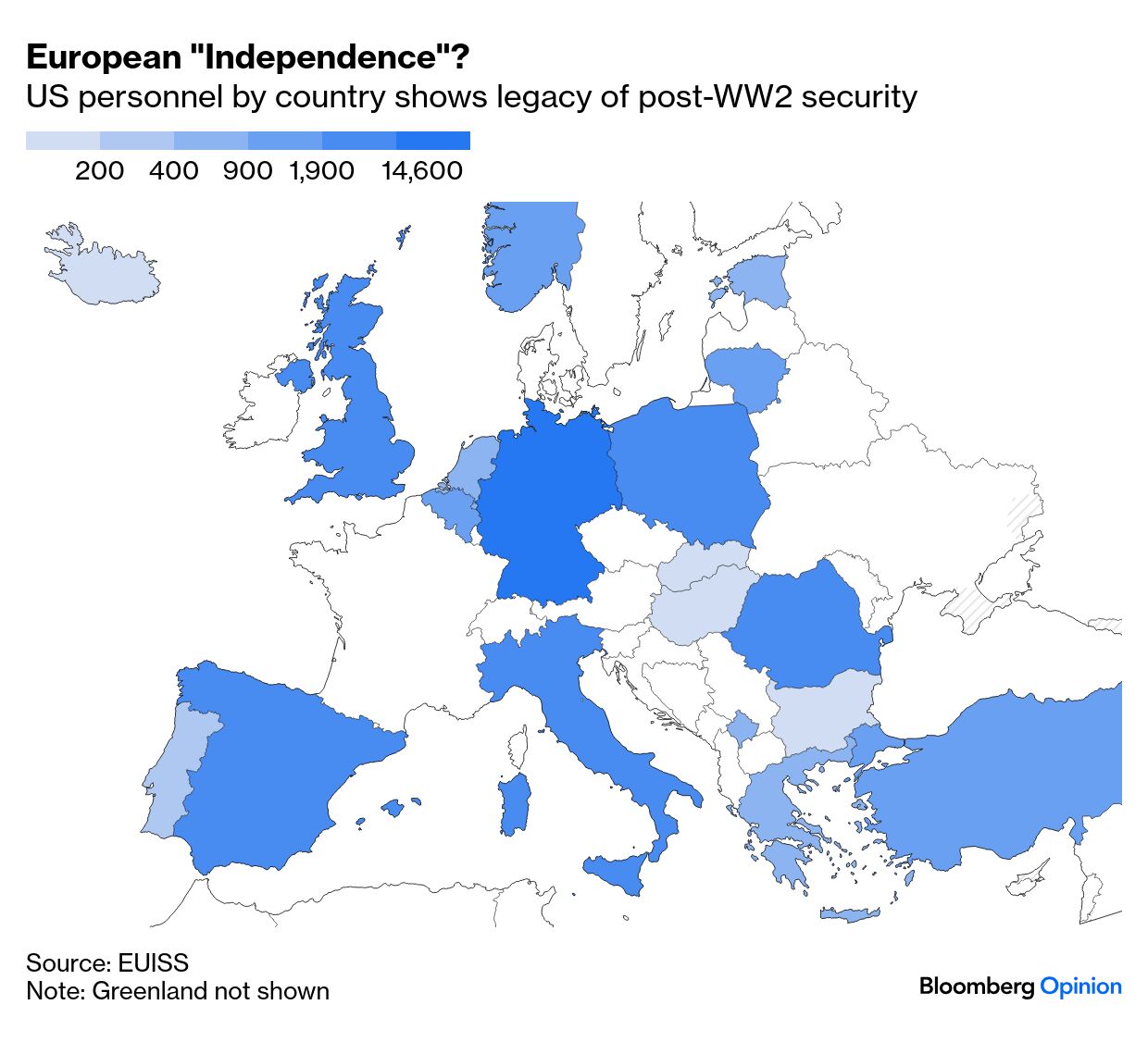

But if we follow the instincts of some on the US political right and formally withdraw from the alliance, pulling our nearly 100,000 troops out of Europe (which will be costly, because much of their garrison costs are born by the allies), or “defund NATO,” the organization will collapse. US warships based in Europe, a huge operational geographic advantage for the Navy, would return to US ports. Squadrons of fighters, transports and surveillance planes would also withdraw.

What might rise in its place? Possibly a European Treaty Organization, or ETO. It could be based on the current NATO treaty, but excluding the US. Canada might choose to remain in an ETO; Prime Minister Justin Trudeau flew to London for the emergency meeting over the weekend, and his nation needs European security partners in the Arctic.

Alternatively, a new security arrangement could be created under the auspices of the European Union (including non-EU member Britain). The EU already has reasonably well-developed command structures, a supreme commander — called the chair of the EU Military Committee, who was my counterpart a decade ago — and experience conducting operations independently of the US or NATO, for example in Balkan peacekeeping.

This would be terra incognita: No nation has ever fully withdrawn from NATO. But if the US simply decided to step away from NATO, I predict the Europeans would do three things.

First, they would continue to ramp up their defense spending, particularly by increasing their nuclear capability (the UK and France are already among the world’s nuclear powers). They would increase their aerospace forces, both for offense and defense. Spending on intelligence, cyberwarfare and space operations would rise, and compete with US operations. And given the threat of Russia, they might even consider broader conscription (a few of the European countries, including new NATO members Sweden and Finland, currently require forms of military service).

Second, the Europeans’ foreign and defense policies would rapidly split from those of the US. Instead of confronting China alongside Washington, they might seek greater economic and perhaps even military cooperation with Beijing, as a hedge against growing US alignment with Vladimir Putin’s Russia. More European nations will likely join Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative. Europe may be far less inclined to join with the US in pressuring Iran over its nuclear program, and instead seek economic advantages there. And they would poach American trading partners, especially if a NATO withdrawal comes in tandem with big new tariffs directed toward Europe.

Finally, Europe would strongly support Ukraine, recognizing that it would be a disaster to capitulate to Putin’s conquest of the agrarian and mineral-rich nation: If superimposed on the map of Western Europe, it would reach from the Mediterranean to Britain. Europe simply cannot cede it to a hostile Russia.

There is an old saying about why NATO was created: “To keep the Germans down, the Americans in, and the Russians out.” If the US decides to go its own way in the world — as it disastrously did in the 1920s and 1930s — that equation would be obsolete. The new expression could be: “With the Americans out, and the Russians trying to get in, the Europeans won’t be held down.” I’m hoping the transatlantic bridge isn’t going to buckle entirely, but I can certainly hear it creaking loudly. If it collapses, it won’t end well on either side of the Atlantic.

Stavridis is dean emeritus of the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University . He is on the boards of Aon, Fortinet and Ankura Consulting Group, and has advised Shield Capital, a firm that invests in the cybersecurity sector.

More From Bloomberg Opinion:

- Trump Isn’t Playacting When He Invokes Napoleon: Timothy L. O’Brien

- Only the Supreme Court Can Stop an Unprecedented Power Grab: Noah Feldman

- Ukraine Can Survive With the ‘Least Worst’ Peace Deal: James Stavridis

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO> . Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter.