Into the Wind

Length: • 13 mins

Annotated by Mark Isero

When I met Jenn in 2008, I didn’t know what to make of her. She was radiant. And tiny. When she was riding, she was stronger and fiercer than anyone I’d ever seen. She flowed up hills like she was a part of them. I watched her the way young people watch those slightly older than themselves: I absorbed everything.

There wasn’t anything specific I was looking for. I just understood—or believed, or imagined—that this person had broken out of something that I also wanted to break out of. She seemed to be fully herself, and to have found real joy.

The previous summer, I’d moved into an unfurnished apartment in Oakland, California, with my best friend Ava (not her real name). We were honors students finishing up degrees in philosophy. During the day, we’d pace the empty living room, debating theories of freedom and authenticity. We wanted to know all the true things about the world, and it felt like our lives depended on it. At night we danced for money.

By then I’d stripped in a half dozen clubs, and dancing on stage seemed like a great deal: I got paid to wear glitter and twirl around! Each night was an absurd festival of human desire, raw and unfiltered. It was more interesting than working as a waitress; more bluntly educational than many of my college classes. I planned to use my earnings to become a mountaineer and then build a small homestead. At night when I glued on my eyelashes in the dressing room mirror, I saw myself as a subversive beatnik success story.

Join Bicycling for unlimited access to best-in-class storytelling, exhaustive gear reviews, and expert training advice that will make you a better cyclist.

But there was a complexity to my role that, at 22, I hadn’t factored. To be wanted by men, I had to do what men wanted, and this was not always in my best interest. Some men touched me when I didn’t want to be touched. They bit and scratched, and said things that made my skin crawl. They wanted me to be smaller, younger, more malleable. I didn’t know how to process the bad things that happened, and I didn’t know how to discern role from identity. I treated the men at the club as if they were my real friends, and I still think some of them were. But some were not, and these experiences crushed me.

I started to drink when I worked, and to take painkillers. Numbness made the job possible. Ava was a star runner with a brilliant, vibrant mind, and she had a habit of taking things to the edge and then beyond. She started working for a pimp who carried a gun. Sometimes I picked her up from an old warehouse across town, and when she got in the car her eyes were glassy, like she was in a trance. I adored her, but I didn’t know how to help her. It was no longer clear what was happening to us.

I thought I was tough enough to handle anything, but finally I had to admit I wasn’t. Something about the job was destroying me from the inside out. I began to fantasize about walking on stage in ratty sweatpants and taking a nap. I imagined drawing dollar signs on my limbs and auctioning myself for parts. Eventually—to the great confusion of the Friday night crowd—I added Simon and Garfunkel’s “I Am a Rock” to my playlist, and stripped ironically to its mournful lyrics. On those nights I didn’t make much money, but at least I felt like myself again.

There is a fine line between losing yourself and finding your deepest truths. Sometimes there is no line at all. In my body, I knew things that didn’t make sense, things I couldn’t cover up, or ignore, or laugh away. I wanted to be whatever men wanted me to be. Even when it was bad for me, even when it erased me. The club was a distillation of a social narrative I had grown up with my entire life and did not know how to separate from. It was a part of me, and I was a part of it. I craved the stage, the darkness, the flutter of cash. Each time I quit, I swore I’d never go back. But I always went back. I always went back, because I always wanted to.

■

Finally I left the club and got a job as a mascot for an aquarium in San Francisco. Each day, I wedged myself into a huge, full-body costume of a male scuba diver and lumbered around the pier, waving. I was accompanied by a young man with a combed-over Mohawk whose job was to make sure I didn’t run into a post. When we tired of walking, he’d sit me down on a bench and I’d pretend to be a statue. Once, I got to wander on stage at a children’s music festival; I threw my arms in the air and danced with everything I had.

When the lease on our apartment ended, Ava moved in with one of her customers and we drifted apart. I felt like I had failed her, and us. I moved onto a sailboat with a sailor I met at a bar. He was kind and handsome, and I loved sitting with him on deck while the boat rocked and the sun sank over the bay. But everything felt temporary. I knew I couldn’t stay.

There was only one solution, and that was to leave everything behind: to undo myself completely, to free myself from my own motivations. I turned in my mascot costume, sold my car, and got rid of my things. I said goodbye to Ava, the sailor, and everyone I knew. Then I boxed up my old chromoly steel Windsor Tourist, packed my camping gear, and bought a one-way ticket to Alaska.

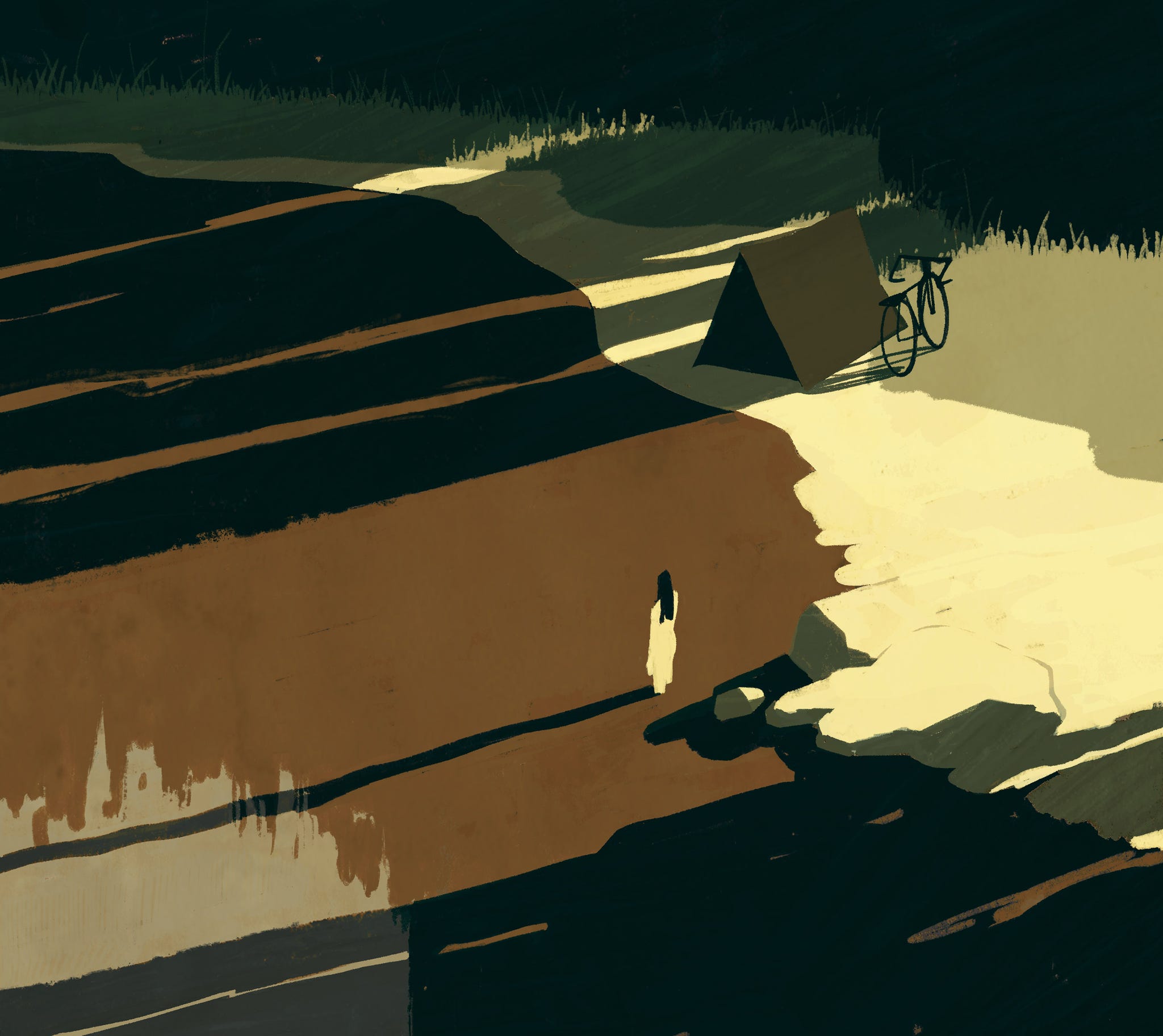

Katherine Lam

Alaska was wilderness, the great unknown, a place of wide skies and rebellion. I longed to merge with its magic. A couple years earlier I’d biked alone around Iceland, and by the end of that trip I’d felt almost feral. Maybe this time I could become fully wild. I didn’t know how to be a person and be female at the same time. So I figured, maybe I didn’t have to. I imagined myself as a moose, a bear, a pink-speckled salmon.

The plane touched down in Anchorage and I found my bike box in the baggage claim. I dragged it to a corner, removed the bike, and sorted my gear. I didn’t know where I was going or how long I’d be gone. It was late May, and my only plan was to ride south and figure it out on the way. I crammed everything I had into four giant panniers, wheeled my bike to the exit, and pedaled out.

It was early morning and the city was cold and gray. All the years of power and powerlessness welled up inside me and ignited like rocket fuel. I pedaled hard out of town, tears streaming down my face, bike careening under the weight of my bags. The gray of buildings disappeared and forest rose up around me, stark and lovely. This was the wilderness I longed for. I didn’t know what I was doing there, but I knew that I belonged.

I pedaled until evening, and then wheeled my bike into the forest to set up camp. The air was cool and damp. I ate some food from my bag, and then wandered into the woods with my food sack and a rope. I’d read that grizzlies run from the sound of voices, so I sang loudly as I hoisted my food sack into a tree and returned to my tent. Then I crawled into my sleeping bag and curled up to sleep. This was my new life.

Each morning, I woke up, packed up, and pedaled onward. Alaska landscapes are vast and rich, and it was easy to disappear into the expanse. I crossed snow-covered mountains, wound along sparkling blue bays, and glided through long sections of dense, magical forest. I drank from streams and bathed in lakes. I didn’t have a smartphone, music, or any other distractions, and my only source of navigation was a paper map. When the road rose into a mountain, I climbed; when the sky opened into rain, I got wet. The only option was to pedal and accept. Cars passed me, but otherwise I was alone. Solitude was its own kind of freedom, and I embraced it.

After a few days, I crossed the Canadian border and continued into the Yukon. The trees here were smaller and windswept, and the forest seemed to go on forever in all directions. Bears ambled by on the roadside, and I sang to them as I passed. Days turned into weeks, the Yukon became British Columbia, and slowly I dissolved into the joy of flow. Every pedal stroke became part of the rhythm of breath and motion. Every thought and feeling became transient, like the sky. I cried a lot as I rode, often from gratitude, and these tears seemed to cleanse me from the inside out. It didn’t matter what I looked like out here or what anyone thought of me. I was free to fall apart, and inside that dissolution, for fleeting moments, I felt whole.

Despite my solitude, human kindness arrived out of the wilderness in ways I hadn’t anticipated. One day at a grocery store in Alaska early in my journey, an older woman saw me, sighed, and took me home with her for dinner and a warm bed. The next morning, her husband plopped me in a small boat and we cruised around a lake, looking for bald eagles. Another time, in British Columbia, a red pickup pulled a U-turn and the driver handed me a note with directions to her family’s farm. I spent the next day riding horses with her daughters, and in the evening we all went to watch the husband’s theater troupe perform a play about hockey. People looked out for me and included me when there was no reason to do so. The big landscapes humbled me; so did the kindness of strangers. There was no reason for any of this beauty, but it was still here, and that meant something.

Cycling was also hard, and as the miles passed, the hardships of the journey began to take their toll. I pedaled through wind, rain, and sometimes snow. My sleeping pad sprung a slow leak, so each morning I woke up flat on the ground, the pad deflated. My tent also started to leak, and I was often damp. I became so tired that sometimes I stopped riding and lay down on the side of the road to nap; once, a man pulled over to see if I was dead. I loved the magic of the open road, but a part of me started to wonder if my animal life also had its limitations. How long would I be able to go on like this?

■

After nearly two months of pedaling, I crossed the border back into the continental United States and continued down the coast. To my great surprise, I began to see other cyclists loaded with panniers, just like me. One day in northern Oregon, I wheeled my bike out of the bushes where I’d camped overnight, and nearly hit a cyclist heading south. He was a New Zealander named Hugo, and he explained that the road was part of the Pacific Coast Bike Route, mapped by the Adventure Cycling Association. The route started in Vancouver and ended in southern California. He showed me a guidebook where all the mileage, campsites, and water sources were already mapped out. It was a revelation.

I followed Hugo to the next campsite, where I met a small herd of other cyclists, all of whom had the same guidebook. As people crowded around the picnic table, I realized that I no longer knew how to interact—I rarely made extended conversation with anyone. But everyone accepted me as I was, and soon we were all laughing and trading stories. It reminded me that no matter how difficult it was to be a person, it was still worth trying.

I started biking with Hugo and a small, shifting group of cyclists from around the world. There was a German priest who hummed to himself as he rode; an American couple on folding bikes with tiny wheels; college students on summer break. Most people wore neon jackets, took regular showers, and knew where they were going. Hugo was a fast rider who’d biked long routes around the world, and he kindly explained things I’d never heard of, like “cadence” and “cornering.” I felt like an imposter infiltrating a secret society, and this delighted me. I belonged to something I’d never expected to belong to.

One day at a campsite in Oregon, we picked up a British woman who was also biking solo. Her name was Jenn Hopkins, and she’d just finished racing 2,700 miles on the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route across the Rockies. In 28 days, she’d become the first woman to complete the journey on a singlespeed. Now she was biking the Pacific Coast as a “fun ride” after her race. Jenn was 30, with a shy smile and short-cropped hair; she was also clearly a force of nature. I was instantly in awe.

Katherine Lam

Over the next few days, Jenn cycled with us down the coast. Even on her singlespeed, she was by far the strongest rider, and I got used to watching her stand in the saddle and fly past me over passes. Hours later I’d find her at the next campsite, sitting quietly and welcoming us with a smile. When someone’s derailleur broke, she knelt by the roadside to fix it. When I arrived late at a campsite, her encouragement made me glow. She never seemed to try to be anything but who she was, and that made her easy to idolize.

One evening at the picnic table, I worked up the courage to ask Jenn why she chose to race over mountains. She looked at me, cocked her head, and smiled. She said she was out there because she loved it. That every morning she woke up excited to ride, and every day on the bike was a good day. Something clicked inside me.

The headwind on the coast was fierce, and one day we all formed a line to shield each other from the force of the gusts. Jenn explained how we’d each take a turn at the front, breaking the wind for the rest of the crew, and then fall back to the end, letting the next person pedal forward. I’d never done anything like that before. I tagged on at the end of the line, sticking close to Hugo’s wheel. Jenn took her turn at the front and then drifted back, behind me.

We rounded a bend and the trees opened into seashore, waves crashing into sand. Then Hugo’s wheel drifted left and I was in front. I pedaled into the wind, salt spray whipping at my face, keenly aware of the people behind me—people who led interesting, vibrant lives. A rush of elation rose in my chest. My body was useful in a way that finally made sense. In that moment I understood: Joy was its own form of power. It flowed through people, through landscapes, through wind and motion. It radiated from the body and was stored there, too. Joy was limitless and easy to share. After all these miles, I’d arrived somewhere.

The moment passed quickly, as they always do, and we continued onward up the road. I drifted to the side and the back, and Jenn took her turn riding into the wind. I thought about where we’d camp that night, and what I’d eat for dinner.

■

Over time, our crew dismantled, each person returning home or continuing their own journey. After 3,500 miles, I ended my trip in the mountains in Sequoia National Park, and then boarded a bus to Colorado. A few weeks earlier I’d stopped at a library and applied for a job on a forestry crew in Durango. It was my next step in “figuring it out on the way.”

Years passed and life unfolded. I changed and changed again and so did everyone I knew. In our thirties, Ava and I reunited and picked up right where we’d left off. We spent a long weekend wandering San Francisco, untangling the heartbreaks of the past and laughing about nothing on the grass in the park. It was good to be with my friend again.

I kept cycling and went on more long trips. In Ecuador I pedaled across misty mountains; in Costa Rica I zigzagged rocky back roads. Hills rose and fell, people waved and smiled, the road wound onward. These journeys were not hobbies, they were my soul, and I sculpted my life around leaving. Cycling was a way of staying in motion and coming home to myself. When nothing else made sense, I could go—dissolving into breath and sky—and let the wind rearrange me.

Sometimes I thought about Jenn riding through the English countryside, cranking up hills with her ethereal smile. I knew she was out there every day, pedaling, and this comforted me. In my mind she rode the same loop, over and over again, from sunrise to sunset. It was odd, really. She’d slid through my life so quickly and so quietly, yet inhabited a permanent place.

By the time I decided to look Jenn up again, more than a decade had passed. I’d meant to reach out sooner, but life is like that. I sat down at my laptop and googled her name, excited to finally reconnect. The internet can be so crass in its delivery of bad news. I found her picture; then articles about her cancer; then articles about goodbye. I kept scrolling, throat tightening. It had happened suddenly, a number of years after our ride on the Pacific Coast. She was 37.

For months, I kept going back online to look her up again. I kept thinking that maybe I’d gotten it wrong, that I’d read about some other Jenn. But it was always her, peering out from the screen with the same smile I remembered.

I’d shared such a short time with Jenn, but as I’d grown older, the importance of that time grew, too. It had expanded into a part of my own identity, a mindset, a certain hopefulness about what it means to be a person. Meeting Jenn and riding with her had reminded me that it’s enough: that the joy of being a body in motion is enough to build a life on. It’s enough to get you up in the morning. It’s enough to connect you with people you love and people you don’t yet know. It’s enough to keep coming home to, over and over again, for the short time that we’re here.

Laura Killingbeck is a freelance writer and lifelong adventurer. She writes a unique adventure newsletter called Laura’s Stories. You can follow her adventures on Instagram and Facebook.