https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/my-father-the-cyborg/

Length: • 17 mins

Annotated by Mark Isero

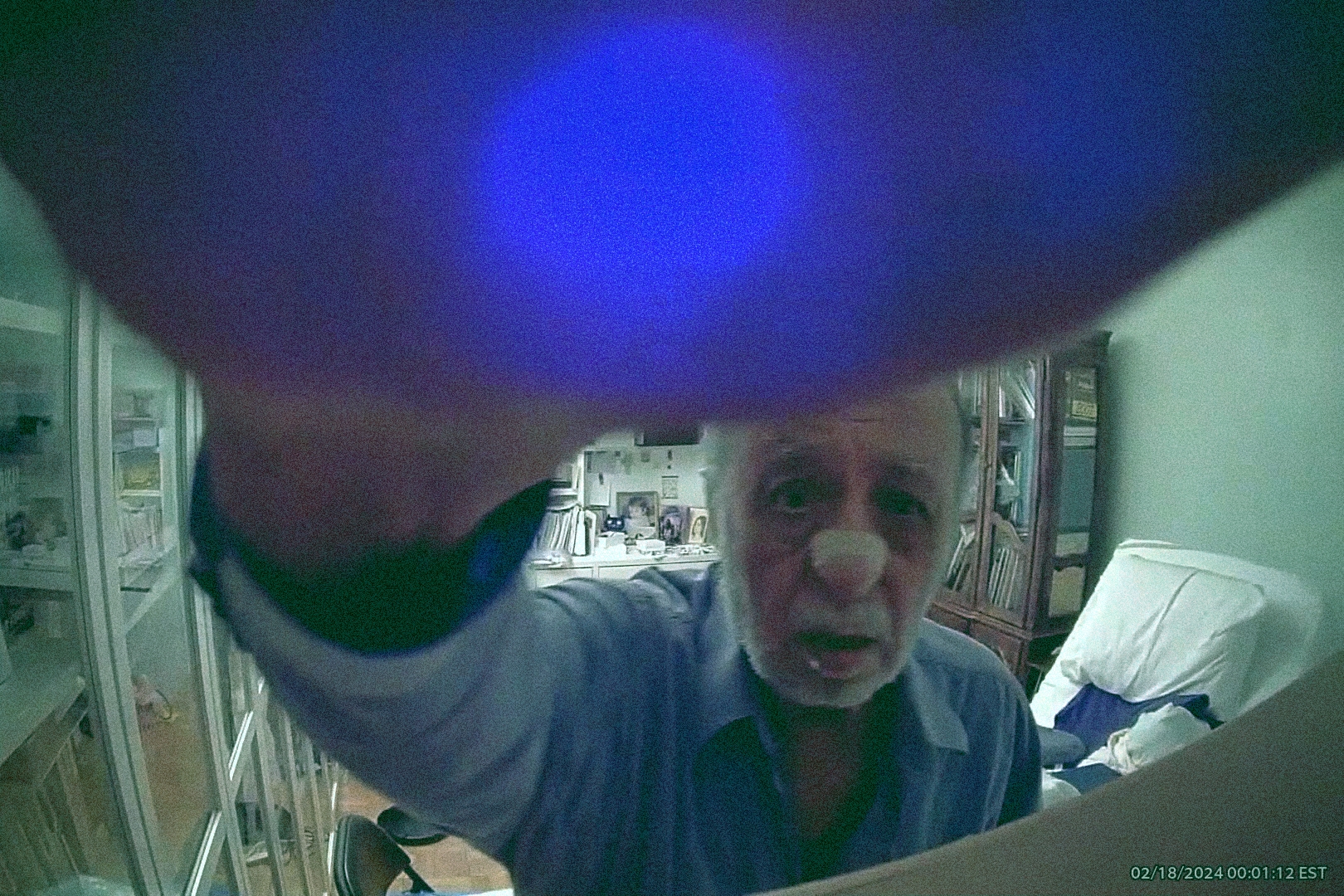

This past February, I noticed that one of the cameras at my parents’ apartment had gone dark. I scanned through the footage: backward quickly, until I saw my father shuffling about, like a stop-motion marionette, then forward slowly, as he approached the camera, reached out a hand, and flipped it down. The cameras were just one of many technological interventions I had introduced into the caretaking plan for my father. And though he sometimes protested, this was the first dramatic register of his unhappiness.

We often talk about the risks technology poses to children. The Senate recently held a hearing about it. But we do not often talk about the risks technology poses to the elderly. And when we do, the concern is for their vulnerability to scams and Facebook data collection. But there is another danger, one with the potential to inflict more than just financial harm: their meddling children. I am one of these meddling children, and even with the best of intentions, I’ve found myself encroaching on my father’s autonomy.

My father is eighty-nine, and if you name a malady, he’s probably got it. They accumulate and constrict. I brought technology into his life to improve his health, increase his independence, and broaden his world (increasingly, access to technology determines the world a person “inhabits”). There wasn’t much discussion before a new technological intervention. Each one seemed harmless and helpful. I gave a superficial explanation, he made a gesture with face and hands that was his equivalent of a shoulder shrug, and something new was unceremoniously introduced. But once in place, these interventions became levers of control.

I brought technology into my father’s life to improve his health, but it soon became a lever of control.

Wearable tech gave me access to his health metrics. From my living room downtown, I monitored passively for signs of danger. But continuous measurements of blood sugar, blood oxygen, step counts, sleep times, standing times, and more were suddenly available to me and difficult to ignore—after all, his health was at stake. And more could be inferred from the collected information than I had anticipated. For example, I had begun monitoring his blood sugar only to watch for drops to dangerous levels, but was soon looking for patterns in the data—asking him what he ate when the 9:03 a.m. spike occurred or accusing him of injecting too much insulin so that he would later have no choice but to eat fruit. Sometimes he seemed genuinely interested in adjusting his habits. And sometimes he bristled at being lectured to—but never so forcefully as to make me question whether I had done something wrong.

Other technological interventions followed the same pattern, starting from the same point of mutual naivete that they would help him. I enabled location sharing on his cell phone so he could go out on his own, installed cameras to monitor for falls so he could be left home alone, downloaded hospital apps to help him correspond with doctors—but all, however well-meaning, especially when added together, ended up invasive and controlling.

When I noticed my father’s blood sugar spike at odd times, I realized I could check the cameras to investigate why. Then my mother was able to find and trash the sugary snacks he had been sneaking. I gave my father an iPad and taught him how to use it, only to deny him access to his favorite news apps because they incensed him. The hospital apps gave us reports from doctors’ visits that my father had ignored or lied about. Even the absence of information became information: if there were no alerts from cameras, then I knew my father hadn’t moved and I should prompt him to do so. “Have you walked today?” I’d ask innocently on a phone call. As with everything else, sometimes he would dutifully comply, and sometimes he would snap at me: “Would you all leave me alone!” But I would not leave him alone. And since his facility with technology is limited and his position of dependence conspicuous, he had no recourse.

More than 7,500 physiological and behavioral metrics can be measured by wearables. But we have barely scratched the surface of what is possible. Thin, flexible, wear-it-and-forget-it biosensors are coming to measure from within, household sensors from without. All manner of data, from hormone levels to brain waves to hand-washing habits, will be continuously collected and triangulated with an eye toward not just managing health conditions, but predicting and preventing them. And as this technology advances, the available levers of control will multiply. Even now, ethics and legality aside, I could theoretically set up a system to lock the apartment doors when metrics indicate my father is walking unsteadily. Or I could use hospital apps to tell doctors everything my father hides from them. And there is the potential for all the gathered information to be used in a court hearing to determine his mental capacity—meaning that by sharing their data, an elderly person might unwittingly be assisting in their own future complete loss of autonomy.

This should sound unsettling. But the focus on my father’s blood sugar improved his eating and injection habits. Removing aggravating apps left him calmer and more focused on his work. The ability to access accurate information about his doctors’ visits proved crucial in keeping him healthy. A healthy, calm father was easier for my family to contend with. And the monitoring tools allowed my family (especially my mother) to have a life beyond caretaking.

So was my use of technology “wrong?” Had I weighted health outcomes and ease of caretaking too heavily relative to autonomy? Did I apply a filter to a raised voice I had become inured to over the decades of my life? Did I see consent where in truth there was resignation? Had I spent so long caring for my father that he had transformed from person to project? I reached out to Dr. S. Matthew Liao, the Director of the Center for Bioethics at NYU, for advice.

Had I spent so long caring for my father that he had transformed from person to project?

“One thing bioethicists might consider is the Parity Principle,” Dr. Liao told me. “In this case, you might say that if something is ethical to do in a low-tech way, it is probably okay to do in a high-tech way.”

Before cameras and blood sugar monitors, my family could peek inside rooms or rifle through cabinets to uncover what my father was eating. That’s how we found out he hid Diet Coke in empty cans of Spindrift. Had technology really changed the ethical considerations? Or had I freighted normal family entanglements with sinister implications because they included today’s digital boogeyman?

I think the former. My father’s ability to hide what he had for lunch—even when he didn’t exercise it, even when he did but failed in the attempt—allowed him to maintain agency. Technology robbed him of this ability. Furthermore, without the need to interrogate him about what he ate (or discover it surreptitiously) there were no natural checks on our temptations as concerned caretakers; technology is impersonal and allowed us to collect unlimited data about him without the discomfort of human engagement.

We see something comparable in medical institutions, where a desire to be thorough can lead to a cascade of tests and questionable intervention. Hence experts’ opposition to full-body MRIs, despite the comprehensive health data they provide. New technology risks importing this dynamic into the home. If its promise is preventing and treating illness in those we care for, we may instead get a degree of behavioral and medical intervention that does more harm than good—especially since it is not necessarily a lack of metrics that prevents people from being healthier, but different priorities, such as pleasure.

But suppose, for a moment, that the Parity Principle does hold true here. Suppose the high-tech approach differs from the low-tech one in methodology alone. Would this imply not that the high tech is ethical, but that the low tech is unethical? The stark and obvious nature of technology casts old ways of doing things in a harsh light. In other words, our surveillance, though now more extreme because of technology, may have always been wrong.

“What about being completely transparent with your father about what you are doing and why?” asked Dr. Liao. Any family with an elderly parent is familiar with the minor conspiracies needed to keep them alive. Over the past decade, a deep state had emerged within mine. Even getting my father to the doctor required subterfuge—not just to convince him to go, but also to keep his pride intact. Half the reason I embraced technology was because it allowed us to be less transparent.

Nor is my father ever transparent with us. And so when he resists, we are left to interpret his true desires. Does he actually want to decide for himself? Or is he expressing frustration at his situation by externalizing blame onto us? Is he acquiescing only because he feels helpless in the digital world? Or is his willpower flagging and in need of augmentation by ours? Perhaps if we could unpeel his mind, all we’d uncover is ambivalence.

Early on in his most recent hospital visit—for his latest malady, failing kidneys—my father asked me to help him pee. I scooped him up into a seated position. He peed into a container I was holding. I felt the container get warm and heavy. Then he told me that he had lived long enough and it was time to go. He was frail and suffering, yet cogent nonetheless. But the doctor thought he was not in a state to imagine how good he could feel once he started dialysis, and, in a bit of circular logic, that his decision about dialysis should wait until after he started it.

The circumstances of how my father came to have the procedures necessary to start dialysis are murky. None of my family members can quite recall. Nothing was forced, per se. But neither do I think that, absent my family’s presence and direction, the procedures would have taken place. Was my father in too much pain to decide for himself or was that very pain the reason to listen to him? Was he even thinking about his current pain or was the prospect of future pain and future hospital visits and years of dialysis what concerned him? Or did my father just not want to be a burden—and if so, did he want us to implore him to live so that he would be the one doing us the favor? I don’t intend to find out. Seven months later he was dancing at my brother’s wedding and that is answer enough for me.

In his book Being Mortal, Atul Gawande describes the frank conversations about end-of-life care he had with his father when the latter became ill. Perhaps because both father and son were doctors, the conversations were fruitful. But even Dr. Gawande’s family was faced with the ambiguity of interpreting previously stated wishes when a life-or-death decision had to be made. Conversations about future care, much like advance directives, often bring confusion rather than clarity. If my father had had an advance directive, it probably would have specified “no dialysis” and “no intervention.” Given his incoherence at the time a decision needed to be made, doctors might have had to obey the directive, even as my family argued with them and amongst ourselves about whether he was informed enough about peritoneal dialysis when he wrote it. In any case, given my father’s pride, it would be cruel and counterproductive to force him to concretize his need in words. He and we have been playing our roles for too long now, and it doesn’t seem wise to disturb the well-rehearsed theater that is our arrangement by introducing transparency.

“Is it possible that your father lacks capacity?” Dr. Liao asked, careful to caveat that this was simply another question a bioethicist might consider. But I had not considered this. Could it be that I wanted so desperately to believe my father was sound of mind that I deceived myself about his mental state? Indeed, whenever he shot out some witticism that indicated a sharpness of mind, I would call my brothers to say “he’s still got it” and we would all breathe a sigh of relief.

Though there are as many definitions of competency as there are ethicists, no authority would ever rule my father incompetent. Does he make bad decisions? Yes. He once had two heart attacks at an airport, refused assistance, and flew across the Atlantic. But the ability to make bad decisions is common to us all: it is only in the elderly that we perceive it as incompetence. In children, it is immaturity; in adults, it is recklessness; but in the elderly, it is a lack of capacity. They alone are not allowed to act dumb.

We tend to overlook the agency of older people. And when someone is under our care, we value their safety at the expense of their autonomy. It is as if the time we spend caring for them adds responsibility for and removes humanity from them. But if I can choose to go cliff diving, an elderly diabetic can certainly choose to eat cake.

The ability to make bad decisions is common to us all: it is only in the elderly that we perceive it as incompetence.

My father’s world has shrunk. Here is a man who has had three different lives in three disparate countries, pretended to be an Iranian prince in Japan, fought in wars, invented farming equipment—and is now reduced to a regimen of pills, YouTube, dialysis, and the winding down of his business. With life so narrowed, with so few things left to choose, the minutiae of daily life—what to eat, when to sleep, what to watch—take on outsized importance. Especially within this limited sphere of his, he has the right to make bad decisions. And if a technology interferes with that right, it is wrong to use it.

And yet my father would have died many times if not for my family’s interference. So even if it is “wrong,” we will not stop meddling. Where does this contradiction leave us? A slight detour into the future is necessary to attempt an answer.

I have come to think of my father as an octogenarian cyborg. To understand why, it is helpful to understand how he sleeps. On his face is a close-fitting mask, connected by an elephant trunk–like accordion tube to an APAP machine, which delivers just enough air pressure to ensure his airways stay open, adjusting pressure as necessary by monitoring his breathing. Sticking into his upper arm is a continuous glucose monitor, waking him up if his numbers are precariously high or low. Around his wrist is an Apple Watch, continuously collecting health metrics for later analysis. And from his belly protrudes a catheter, like a regenerated umbilical cord, which connects to a dialysis machine that circulates a solution in and out of his abdomen, absorbing and then removing waste and extra fluid from his body. The machine collects data throughout the night and relays it to his healthcare provider. Even his bed plays its part, articulating via remote control to keep his torso (for breathing and dialysis) and legs (for circulation and swelling) up at an angle.

Dr. Andrea M. Matwyshyn is credited with coining the term “Internet of Bodies” (IoB). In her so-titled 2019 paper, she defines IoB as “a network of human bodies whose integrity and functionality rely at least in part on the Internet and related technologies, such as artificial intelligence.” She details the many threats human bodies and autonomy will face from these technologies—what happens when an implanted device is hacked, or when a patent infringement case forces an implanted device to cease functioning?—and discusses the legal and regulatory challenges we will face in protecting ourselves. But even as the devices in question are internal, the threats and solutions she locates are external to us—they are in the hardware and software, in the corporations and courts and regulatory bodies. In short, though her concerns are for the personal, the dangers she identifies, while very real, are impersonal.

The threats that animate me are in the personal, internal to us and our social circles. Stood up against Dr. Matwyshyn’s concerns, they are pathetic. But they are no less dangerous. What drives them is an inversion of her coinage: What happens when the body becomes the internet? What happens when we surf the multitude of data our physiology generates like we now surf the web? How will we be changed by the collision between this exciting new data and our narcissism (made robust from a steady diet of social media), predilection for self-diagnosis (helped along by an internet that has come to rival authority), and addiction to technology?

The first threat will come from monitoring ourselves. Even more than our merger with machine parts, it is this monitoring that will change us. My father is addicted to his continuous glucose monitor, managing the number up and down through food and injections. He intervenes far more than he did before the device, when he had far less information. It is unclear if this extra intervention has been positive, negative, or neutral for his health. But it is quite clear that a too-large part of his focus has shifted from living life to maintaining it.

In a sign of things to come, the company that makes the monitor recently sent him an email with the subject: “Gamify your glucose readings with Dexcom CGM and the Happy Bob app.” In a few years I suspect he’ll see ads asking, “Is it time to upgrade your pancreas?” Because in addition to obsessing over data, self-monitoring will include the mundanity of upkeep. By this I mean the constant software updates, the decisions on when to upgrade implanted hardware, dutifully reading reviews to choose the best nanorobot to repair your gut lining—all the obsessions of modern consumerism brought to bear on ourselves, turned inward with the ferocity befitting the perceived stakes: staying alive.

But what becomes of the human condition when it is reduced to a compendium of illnesses to be treated? To be human is to live a collection of fantasies. It is unimportant what one thinks these fantasies are—a denial of death, say, or a view of ourselves as a unified whole—only that they allow us a fluidity of existence, a measure of ignorance of our mechanistic reality. Can such fantasies persist when we treat ourselves with a vigilance befitting a nuclear reactor? Maybe. Maybe our detachment from reality is ultimately unbridgeable. Or maybe when the mechanistic is made palpable we will feel the panic of being alive and collapse from existential dread. At the very least, IoB devices work in opposition to our ignorance-filled fantasies. By focusing us on the grinding of our gears, they necessarily distract from what it means to be human—which is to live.

The trend toward measuring the self has long ago left the doctor’s office. Almost as soon as they were introduced, continuous glucose monitors migrated outside diabetic communities. There is already a name for an obsession with digital sleep tracking: orthosomnia. And I fear, even as we struggle against what this means for ourselves, even as we yearn for a yesterday when the only advice was to eat and sleep well, exercise moderately, and see friends, we will nonetheless impose this tech on our elderly parents in the name of their health—and might even be viewed as irresponsible if we don’t.

The second threat will come from monitoring others. I have discussed the foibles of monitoring my father. There the world of medicine infringed on the personal through the adoption of technology, relaying metrics from his body to my mind. But there is also a perverse offshoot of social media that concerns me, one that aims to relay a more nebulous human attribute than blood-sugar levels: mood.

Mood is now in vogue in educational circles. Students are taught to locate their feelings along a mood meter (one popular design features a grid with x- and y-axes for “pleasantness” and “energy” respectively), labeling them with the goal of improving emotional intelligence and regulation. Versions of this even exist in preschools (here making use of emojis). The most influential approach, RULER, comes from the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence. It has a corresponding app called How We Feel, which suggests you log your emotions several times a day—and encourages you, unsurprisingly, to share these logs with friends, family, and partners.

The trend toward measuring the self has long ago left the doctor’s office.

But mood measuring is not limited to schools. I was shocked to discover recently that a friend of mine uses an app called Stardust to track his girlfriend’s menstrual cycle. The couple says it gives them clues as to how she might be feeling based on the time of month, which has helped smooth their interactions. I do not know if the notifications my friend receives are derived from population-level data or from what his girlfriend records over the course of time (on a given day she can enter her mood, food cravings, sexual desires, etc.) but it is not difficult to imagine that in the future, the app will draw data directly from IoB devices. Nor is it difficult to imagine that How We Feel will do the same, helping users ensure they are labeling their emotions accurately. And mood will not suffice. Future apps will vacuum up all manner of data in a comprehensive attempt to capture a person’s “state.” This “state,” extracted and separated from our bodies, will be sharable with friends, family, and partners, just as Stardust and How We Feel allow for today, and much like it has become commonplace to share one’s location using Apple’s “Find My.” If social media asked us to share ourselves, IoB will allow us to literally do it.

RULER also encourages school staff (and students’ families) to incorporate mood monitoring into their own lives. A friend recently told me that at her job, they start each meeting with each participant sharing their location on the mood meter. Which is to say that one can anticipate normative pressure emerging from workplaces as well, who will remind their employees to note the “state” of a coworker prior to interactions. This is a deterministic way of dealing with someone, very much opposed to the reactive give-and-take of current life. And, when leveraging IoB devices, it will reduce the human to a set of biological data, which will undoubtedly be filtered through an AI, before being spat back out flatly, with an impoverished understanding of what it means to experience another person: “sensitive,” “turned on,” “lonely,” “dehydrated.” Once one’s “state” is generated and shared automatically, once it becomes passive and routine, whatever value recording and discussing your feelings may have once had will be forgotten.

Under this model, much of the nitty-gritty of reading people and learning how to interact with them will be elided in favor of the smooth. You will know how to deal with someone before you deal with them. Then certain interpersonal skills will atrophy, rendering dependence on the “state” even more necessary. And these lost skills, the interplay of being human with one another, are precisely the ones needed to navigate relationships with those we care about and care for: to learn a person so that we can, eventually, help make difficult decisions for their care. In the case of my father and dialysis, my mother believes that he wanted to be “forced” to do it. This observation, and the ensuing right it creates to abridge his autonomy, are only possible through fifty years of knowing someone without technological mediation.

Introducing technology into my father’s care had a double effect: it alienated him from himself and from his family. It made all of us less human because each of us, including my father, dealt with him in a less human way. He became an experiment. As for what to do, of course I have no answers. There is little in all I have studied in philosophy and gerontology that has served me anything more than a normative function. The relationship I have with my father is not one that can be abstracted. There is a Doctor/Patient relationship and a Nursing Home/Resident relationship, both instances where case studies and the work of ethicists are crucial. But there is no Father/Son relationship. It is a meaningless designation. As such, I’ve found it impossible to go from the general to the specific, from a father to this father. Even the arts have offered little more than a petty reminder of his humanity. The closest I can come to an ethos is this: reduce the mediation of technology in our relationship as much as possible; go back to ways of doing things that are tempered by the need for human confrontation; allow myself to learn him through experience. Because my father doesn’t need me to count his steps. He needs me to walk with him.

And what does my father have to say about all this? He doesn’t attribute any of his longevity to our interference, technological or not. My parents live on the sixth floor and he doesn’t think the angel of death can reach that high.

Independent and nonprofit, Boston Review relies on reader funding. To support work like this, please donate here.

Omer Rosen

Omer Rosen is a writer and app developer based in New York.

Boston Review is nonprofit and reader funded.

We rely on readers to keep our pages free and open to all. Help sustain a public space for collective reasoning and imagination: become a supporting reader today.