Why Tech Billionaires Love the Author of Jurassic Park

Length: • 8 mins

Annotated by Alexander Klöpping

Some content could not be imported from the original document. View content ↗

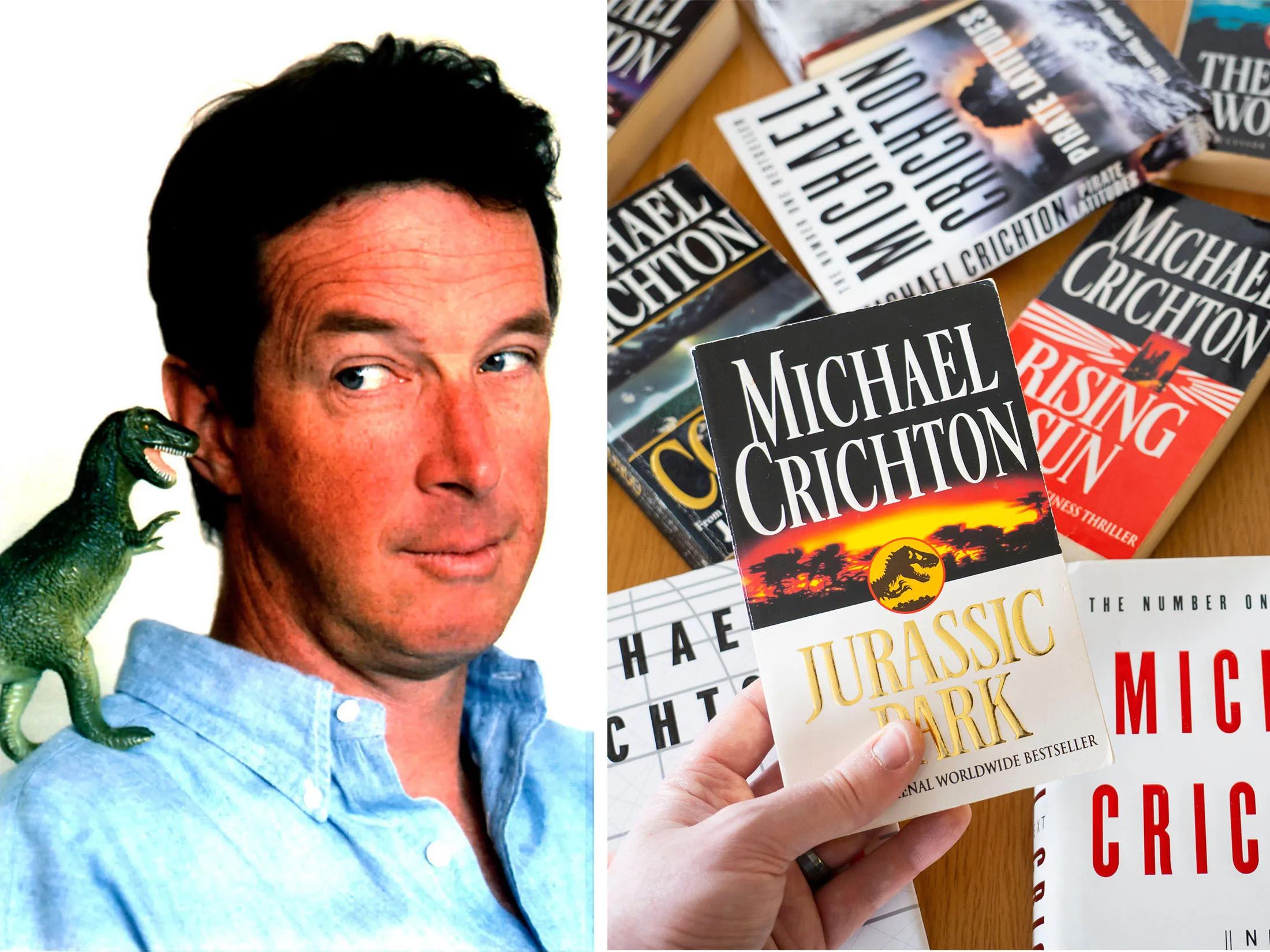

This past summer, venture capitalist Vinod Khosla started clashing online with Elon Musk over Musk’s support for Donald Trump. The two tech billionaires argued about immigration, climate policy and MAGA values before their debating devolved into name-calling. But there was one area they appeared to find common ground on: a decades-old media critique by Jurassic Park author Michael Crichton.

“How many times have you read something in the media where you know the real story, but what they printed was diabolically false?” Musk asked on X, suggesting that press depictions of Trump were deceitful. “Agree on not trusting media,” Khosla replied. Hammering his point home, Musk posted a screenshot from Wikipedia about Crichton’s “Gell-Mann Amnesia effect.”

Crichton coined the term in a 2002 talk at a think tank. He defined it as the sensation of reading a newspaper story in your field of expertise and finding it littered with errors, then flipping the page and taking for granted that the next article, on a subject you don’t know much about, got things right. “In ordinary life, if somebody consistently exaggerates or lies to you, you soon discount everything they say,” Crichton said. “But when it comes to the media, we believe against evidence that it is probably worth our time to read other parts of the paper. When, in fact, it almost certainly isn’t. The only possible explanation for our behavior is amnesia.”

Even as the technology industry splinters politically, Crichton’s theory remains a bipartisan catchphrase, a default response to just about any piece of commentary that Muskies or their left-leaning counterparts disagree with or question. It’s also now a knee-jerk reaction from top tech founders, executives, investors and analysts to any skepticism from outside their bubbles.

What Crichton was really getting at, however, is that people in positions of authority sometimes talk about things they don’t really understand. His new crop of enthusiasts are often just as guilty of this as anyone.

Briefly stated, Crichton’s talk has been co-opted as a pseudoscientific means to dismiss critics without bothering with the specifics. Earlier this year, Meta Platforms Inc. Chief Technology Officer Andrew Bosworth brought up the Gell-Mann effect to validate why he always takes external opinions about his company’s business and products with a grain of salt. All-In podcaster David Sacks has highlighted it to portray tech reporters as channels of misinformation, while Y Combinator cofounder Paul Graham has cited it to discount the view of any journalist talking about things he knows well. Even crypto bulls point to it to scorn what they call fearmongering about NFTs.

Crichton’s concise definition of the Gell-Mann effect is tailor-made for bite-size consumption. “You read the article and see the journalist has absolutely no understanding of either the facts or the issues,” Crichton is quoted as saying, in a commonly screenshotted section in which he recalls reading crappy columns about show business, his area of expertise. “Often, the article is so wrong it actually presents the story backward—reversing cause and effect. I call these the ‘wet streets cause rain’ stories. Paper’s full of them.”

What may surprise some fans is that much of his talk was actually focused on his hatred of pontificators. (Its title was “Why Speculate?”) Yes, he spit dilophosaurus venom at print publications that screw up facts and sneak conjecture into their reporting. But he was equally hostile toward cable-TV talking heads, insulated academics, internet opiners and—in keeping with several of his most famous books—arrogant technologists. “Futurists don’t know any more about the future than you or I,” Crichton said, later ripping into the cheapness of heralding the world of tomorrow. “You can’t lose. Even though the speculation is correct only by chance, which means you are wrong at least 50% of the time, nobody remembers, and therefore nobody cares. You are never accountable.”

It’s not surprising that many people screenshotting the Gell-Mann effect don’t seem to have processed the rest of Crichton’s writing on the subject. Unattributed excerpts make for like-bait, and the original is hard to locate. There are different versions of the text floating around, too. Even the Wikipedia entry that Musk referenced links to a trimmed-down version from Crichton’s bygone official website, apparently uploaded in 2007, the year before he died from cancer.

A key passage from the original talk, which I dug up from the think tank Crichton was speaking to, is missing in the archived webpage. It’s a digression on former IBM head Thomas Watson, who purportedly predicted the world would only need four or five computers. It’s unclear if Crichton was referring to Watson Sr. or Jr., both of whom profoundly influenced the company, and there’s little evidence either of them actually made this forecast. Nevertheless, his point was that even brilliant businessmen and pioneering scientists are guilty of the same sins as the media. “Expertise is no shield against failure to see ahead,” Crichton said. “Not only did he fail to anticipate a trend, or a technology, he failed to understand the myriad uses to which a general purpose machine might be put.”

This theme recurs throughout Crichton’s books, from Westworld to Congo to Prey. In a fashion that could now be considered downright Musk-like, John Hammond, the founder of a genetic engineering startup who brings Jurassic Park to life in that book, seems to gauge the project’s success based on how well he can sell the dream of it. “That great sweeping act of imagination,” Hammond thinks at one point. “Real vision. The ability to see the future. The ability to marshal resources to make that future vision a reality.” (Spoiler alert: In the book, Hammond doesn’t escape the island as soothing John Williams music plays, like in the movie. Instead, his creations eat him alive.)

Crichton preferred when commentators and experts put events in context and shared a point of view on the importance of what had already happened. He loathed when people used their credentials in one industry to justify pontificating on another. You can imagine how this disapproval would have applied to, say, an automotive and rocket engineer opining about the future of the First Amendment, or a former PayPal and Zenefits executive postulating about military strategy in Ukraine.

It’s worth remembering, too, that when Crichton came up with Gell-Mann Amnesia, a pre-IPO Google was still battling with Yahoo. Neither Facebook nor Twitter had been created, and Apple Computer Inc. had just released its first iPod. The great decline of print newspapers and magazines was only just beginning in earnest. In Crichton’s talk, he took the New York Times to task for an article speculating about the possible ramifications of Bush-era tariffs for American consumers. What would he make of all the wild speculation today about Trump’s promised tariffs on X or Threads or YouTube? Or of redpilled influencers and podcasters like Tim Pool, another Gell-Mann effect fan, who claim audiences should trust them over the Times?

Musk has fashioned X as a hub of citizen journalism, which makes Crichton’s theory particularly applicable given the conspiracies and falsehoods promoted on the platform as fact, habitually by Musk himself. Gell-Mann Amnesia is essentially the business model for his Twitter successor. For Musk to make money on his acquisition, many users and subscribers need to forget the ugliness they experienced yesterday and return to the site today. In Crichton’s formulation: You read X posts and see X users have absolutely no understanding of either the facts or the issues. Often, the posts are so wrong they actually present the story backward—reversing cause and effect. Then you keep scrolling until the next post that somehow seems more accurate than the baloney you just read.

A different theory Crichton defined in the same talk is better suited for this social media dynamic. “The There-Must-Be-A-Pony effect,” as he called it, comes “from the old joke in which a kid comes down Christmas morning, finds the room filled with horseshit, and claps his hands with delight. His astonished parents ask why he’s happy; he says, ‘With this much horseshit, there must be a pony.’”

Crichton, it should be noted, had his own just-asking-questions moments about climate change and secondhand smoke. But he also wrote his talk partly as satire. “I will join this speculative trend and speculate about why there is so much speculation,” he joked. He only named the Gell-Mann effect as such because he said he once discussed it with the physicist Murray Gell-Mann, “and by dropping a famous name I imply greater importance to myself, and to the effect, than it would otherwise have.”

He may have been downplaying Gell-Mann’s influence. Five years before Crichton’s talk, at a 1997 computer conference, Gell-Mann delivered a nearly identical commentary. He spoke of the need for society to improve incentives and resources for skilled, well-intentioned intermediaries to extract meaningful knowledge for mainstream audiences “from the immense sea of data that threatens to drown humanity,” and called for more experts in niche topics to speak directly to the general public in lay terms. Presciently, Gell-Mann warned that the digital revolution could lead simultaneously to further globalization—and to a wellspring of misinformation and cultural polarization on the internet. “Crazy conspiracy theories, new superstitions and urban folktales flourish and spread as never before,” he said.

In any case, Crichton’s “Gell-Mann” branding succeeded. Following Trump’s election victory, late-night Fox News host Greg Gutfeld devoted a segment on his show to the scientific-sounding theory. Gutfeld said the mainstream media had gotten so much wrong about Trump supporters during the 2024 presidential campaign that “the Gell-Mann effect went national,” and the country has finally realized it’s all fake news. “Imagine if everyone got this, then none of the brainwashing could work anymore,” he added, unironically. “The goal in the next four years is to unite all sides with one shared enemy: the media.”

Of course, by that logic, the public should’ve already stopped paying attention to Fox News anchors or any other loud voices and platforms that consistently propagate untruths. Ditto technophiles who are demonstrably wrong again and again in predicting what gadget or app or novel paradigm will take off. Which is ultimately where the Gell-Mann concept collapses on itself. After all, it’s a pretty extreme position, the idea that if you consume one piece of commentary with perceived mistakes and faulty conclusions you should therefore disregard anything and everything that writer or media outlet has ever produced. (The inverse seems just as shortsighted: If I read an article in my field of knowledge that happens to be accurate, I’m not sure it’s healthy to take everything else from that publication as gospel.)

Yet that hasn’t stopped tech leaders from adopting the Gell-Mann effect as a defense mechanism, even as they neglect to hold themselves to the same standard. I, for one, don’t dismiss Meta CTO Bosworth’s observations about tech on the basis of his kooky 2016 memo contending that the social network’s unfettered growth was worth unintended consequences like suicides stemming from cyberbullying or terrorists coordinating attacks with its digital tools. (After the memo leaked, Bosworth suggested he was just being provocative to encourage debate. “I don’t agree with the post today and I didn’t agree with it even when I wrote it,” he wrote in a since-deleted tweet.) Nor do I laugh off the rest of Paul Graham’s essays simply because I found one of his pieces on my industry pretty naive. They’re smart, well-intentioned people who occasionally get things wrong. Just like a lot of legacy media.