It's hard to write code for computers, but it's even harder to write code for humans

Length: • 8 mins

Annotated by howie.serious

Writing code for a computer is hard enough. You take something big and fuzzy, some large vague business outcome you want to achive. Then you break it down recursively and think about all the cases until you have clear logical statements a computer can follow. Computers are very good at following logical statements.

Now, let's crank it up a notch. Let's try to write code for humans!

I need to clarify what I mean. I'm talking about code that other humans will interact with. More specifically, I'm talking about the art of crafting joyful frameworks, libraries, APIs, SDKs, DSLs, embedded DSLs, or maybe even programming languages.

Writing this code is much harder, because you're not just telling a computer what to do, you're also grappling with another user's mental model of your code. Now it's equal part computer science and psychology of reasoning, or something. How do you get that person to understand your code?

Feynman famously said: Imagine how much harder physics would be if electrons had feelings. about something very different, but in a funny way I think this describes programming for humans a bit. The person interpreting your code actually has feelings!

Let's talk about some ways we can make it easier.

Getting started is the product

It's obviously great to listen to your users and take their feedback into account. As it turns out, most of that feedback will come from power users who use your product all the time!

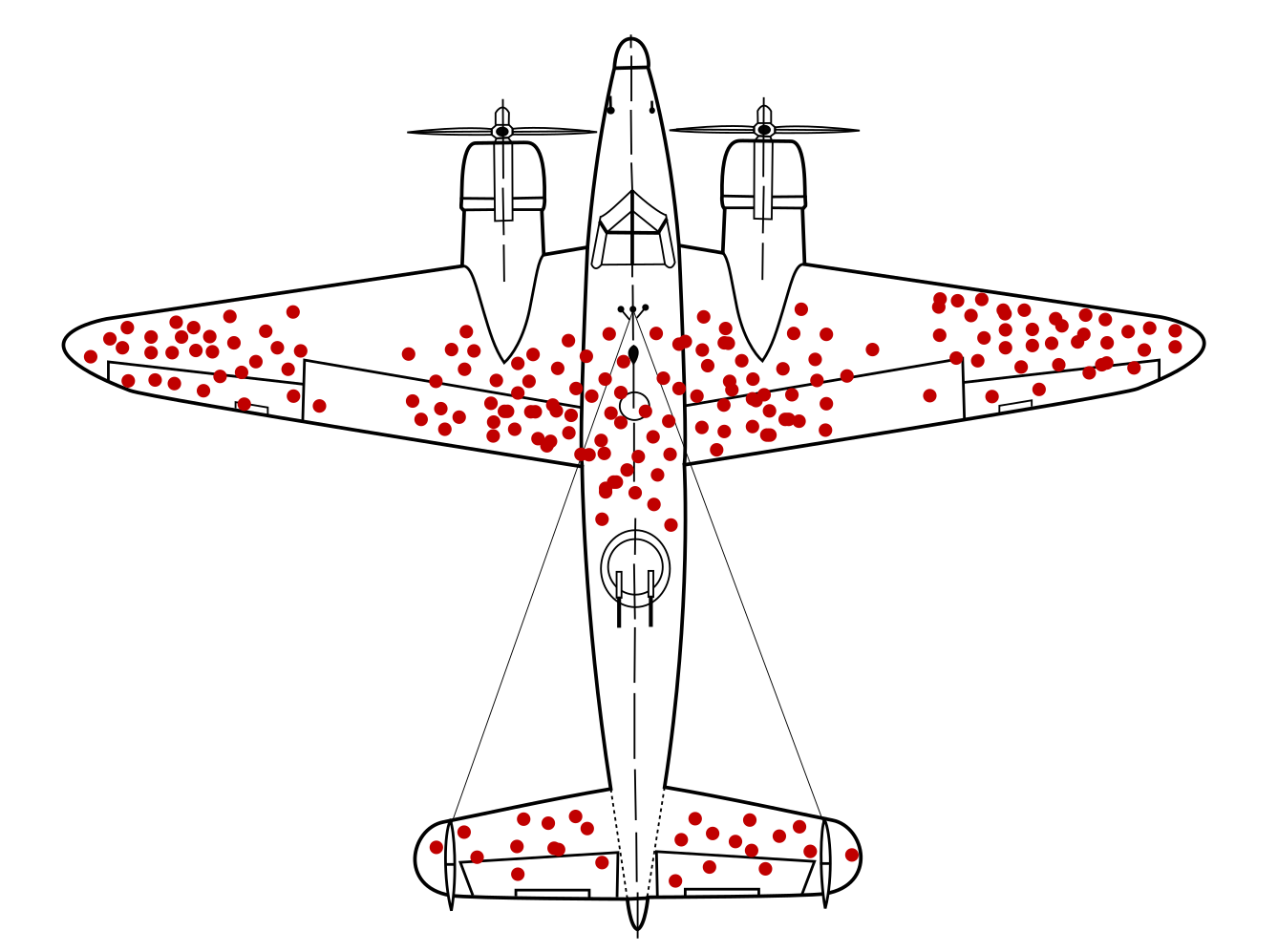

How does that affect the distribution of the feedback you're getting? Will it be skewed? And what does this picture of an airplane have to do with it?

Of course, there's a survivorship bias going on here. There are users who don't use your tool because they never get started. You will typically never hear their feedback!

Consumer products have had growth hackers for many years optimizing every part of the onboarding funnel. Dev tools should do the same. Getting started shouldn't be an afterthought after you built the product. Getting started is the product!

And I mean this to the point where I think it's worth restructuring your entire product to enable fast onboarding. Get rid of mandatory config. Make it absurdly easy to set up API tokens. Remove all the friction. Make it possible for users to use your product on their laptop in a couple of minutes, tops.

You might dismiss this as, I don't know, “who cares about lazy users”. Then let me lean back on my bean bag chair, open a bag of Doritos, and explain something:

There's currently 7,000,000,000 dev tools out there. Users don't have a ton of energy or patience to go deep and try to understand what's different about your LRU cache NPM package or whatever. Sorry!

Humans learn from examples, not from “core concepts”

Humans are amazing pattern matching machines, in contrast to computers who obey Boolean logic and follow strict instructions. It's common to see documentation for dev tools structured like a computer program. It starts with defines a core data model and the relations and the atoms. It starts with “core concepts” and how to configure and how to run things.

Humans don't learn about things this way.

Two seconds after writing the above paragraph, I ran into this on Twitter which basically captures what I'm trying to say:

Too many programming books and tutorials are like “let’s build a house starting from scratch, brick by brick” when what I want to “here is a functioning house, let’s learn about it by changing something and then seeing what happens”

Instead of writing an 5,000 word “core concepts” chronicle, may I suggest putting together a dozen examples instead. This has a few benefits:

- Humans will look at the examples and learn how your tool works from that. This is how humans learn!

- A person with a problem in mind will look for a starting point that's close enough. The more potential starting points, the more likely they are to have something that's closer to what they need.

Falling into the pit of success

The sad but true part of programming is, the default mode is that you're fixing an error of some sort. This means that users are going to spend the majority of the time with your tool trying to figure out what's not working. Which is why pushing them back into success is so core.

A succinct list:

- Developers getting to success faster are happy developers. They will like your tool.

- Developers banging their heads against errors are sad developers. They will blame your tool.

Think about every error as an opportunity to nudge a user towards the happy path. Put code snippets in the exceptions. Emit helpful warnings when users are likely to do something weird. Do what you got to do to make the user succeed.

Avoid conceptual overload

Every new conceptual thing you have to understand before using the tool makes is a new friction point. If it's 2-3 things, that's fine. But no one is going to bother learning 8 new concepts.

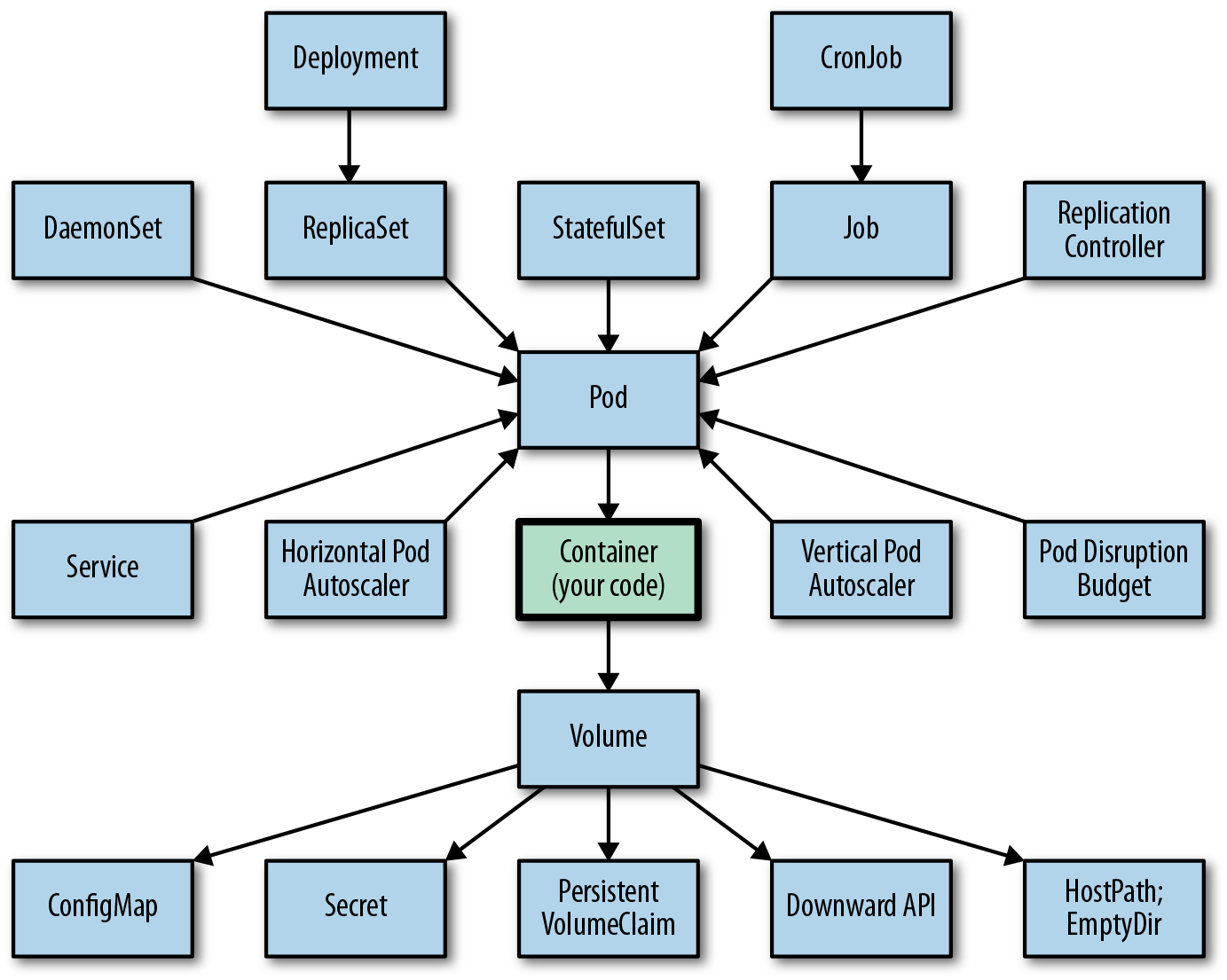

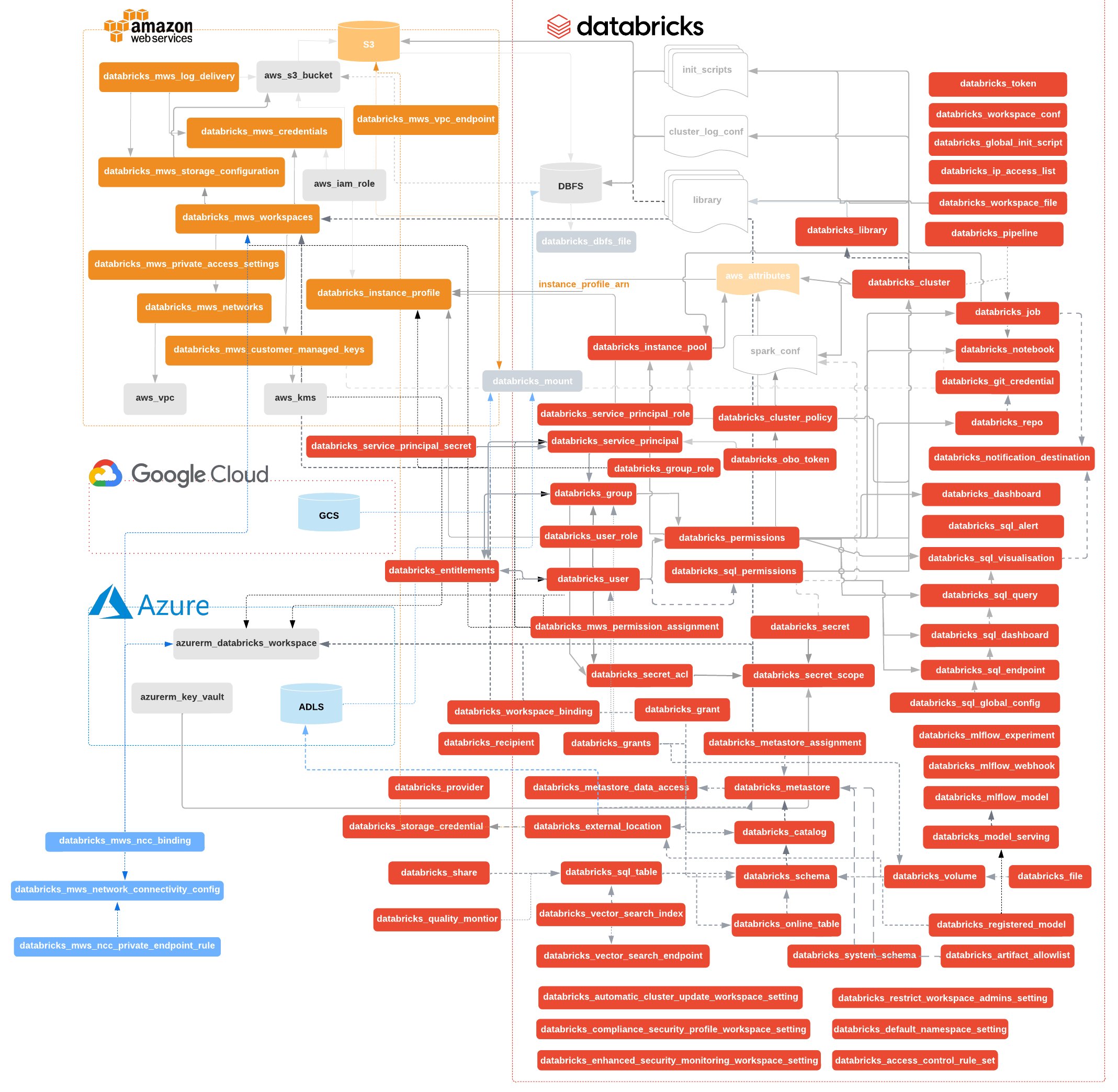

This example (Kubernetes) isn't even particularly egregious. You can get started just knowing a few of these. I mean you can find worse ones out there

It's probably true you don't need the vast majority to get started. But still, my head hurts when I have to learn new things. Too many things!

There's something elegant about a framework with just 3-5 things that manages to be incredibly powerful. I remember the feeling when I tried React the first time and got over the conceptual hump after an hour or two. Just a few fairly simple building blocks that lets you build a whole cathedral. Magic stuff ✨.

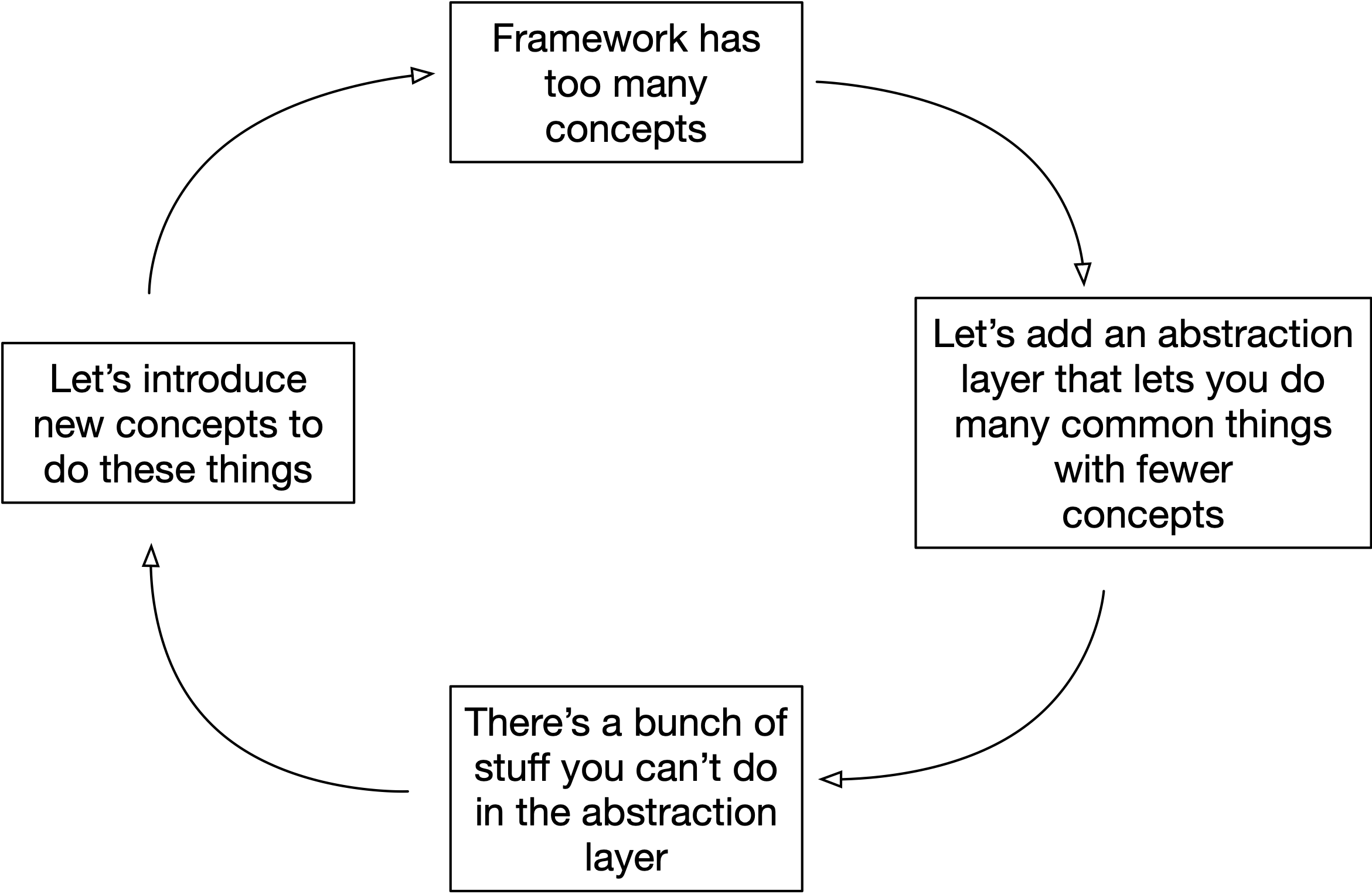

To be clear, the challenge isn't to reduce concepts. It's to retain the possible set of things you can build while reducing concepts. Or at least reducing the former less than the latter. I'm mentioning this because I picture some sort of a “dumb dev tools simplification doom loop” that goes something like this:

I don't know if this is a thing, but my point here is that there's a level of futility of “bad” simplification. You ultimately want to push the frontier describing the tradeoff between “complexity” (what you need to know) and “ability” (what you can build). Amazing tools are able to reduce complexity by 90% while keeping the ability the same, But I'll also take a tool that reduces the former by 90% and reduces the latter by 10%. That's still not bad!

Conceptual duck principle

Somewhat related to the previous point, let's say in your framework you introduce a thing that takes some values and evalutes to a new values. What do you call it? A compute node? A valuator? A frobniscator?

No! You call it a function!

If it walks like a duck, and it quacks like a duck, it probably is a duck.

Maybe it isn't exactly like a function in some subtle ways. Maybe the values are cached for instance. But that's close enough!

Calling it a function means you latch onto a users pre-existing mental model of what a function does. Which will save you like, 90% of the explanation of how to think about this object.

Programmability

People will do crazy things with your codebase. They will take your things and put it inside a for-loop inside a function inside something else. People are creative!

You want almost everything in your framework to be “programmable” for this reason.

This is a whole class of issues that are related in subtle ways and can be solved in similar ways. Let users call things directly in code rather than going through a CLI. Avoid config and turn it into an SDK or an API. Make things easily to parametrize so you can create n things not just 1.

One weird benefit of this is it often lets users discover new use cases for you. Harness people's desire to “hack” on top of your framework. There will be some mild bloodshed coming from those users, but don't chastise them! They might be on the verge of discovering something unexpected.

Be extra judicious about magic, defaults, and syntactic sugar

Let's say you're building a tool that executes a Jupyter notebook in the cloud. So you have a function run_notebook that takes a list of cells (with computer code) or something.

How does the user specify which container image they should use? You have a few different options:

- An argument

image=...that always has to be provided. - An argument

image=...that defaults to some base image with “most” data science libraries pre-installed, but that they user can override. - You inspect the code in the cells and pick an image in a “magic” way based on what dependencies are needed.

- Same as above, but you also let users optionally specify a specific image.

What should you use? If you want to minimize the amount of typing for users, while supporting the widest possible set of use cases, go for the last option. But here are some issues with all options except the first one:

- Let's be real — the magic will break in some % of situations.

- Users reading code that relies on defaults will not realize that things are customizeable.

Unless defaults apply in 97%+ of the time, and unless magic applies 99% of the time, be careful about introducing it. These are not exact numbers obviously, but my point is, you need to be very very judicious.

It's tempting to think that job as a tool provider is to minimize the amount of code a user has to write. But coding isn't golf!

I think about this a bit about how I think about Perl vs Python. Perl tried very hard to optimize for shortest code until every program looked like a strong of special characters and nothing else. Then Python came and it's code was 50% longer. It never tried to be the shortest! But it turned out Python code was super readable and thus much more understandable. And people read code 10x more times than they write it.

Syntactic sugar belongs in a similar category. It's tempting to introduce a special syntax for the most common use cases. But it often obscures the consistency and makes it less clear how to customize code. For similar reasons, unless the syntactic sugar applies 99%+ of the time, it's probably not a good idea to introduce it.

Writing code for humans is hard

We are coming to an end, but there are so many more things I could keep going on about:

- Most things (but not everything) should be immutable

- Avoid “scaffolding” (code generation)

- Make the feedback loops incredibly fast

- Make deprecations easy for users to deal with

- Use automated testing for code snippets in docs and examples

Probably a lot more. Those are maybe things for a future blog post! Including what I think is maybe the most fascinating thing: why large companies are generally incapable of delivering great developer experiences.

I sometimes think the challenge of designing for the 1st time user is similar to making a pop song. The producer will listen to the song a thousand times. But still the 999th time they hear it, they need to imagine what it sounds like to a person that hears it the first time, which seems... super hard.

This is probably why I ended up building dev tools rather than producing pop songs.

Update: this post made it to Hacker News.

Tagged with: software, programming