On Believing

Length: • 12 mins

Annotated by Mark Isero

On Believing

Emerging Writer Series

Every two weeks or so I am publishing an essay from an emerging writer. This week, we are publishing “On Believing” by Rachel Dlugatch. Originally from the Central Coast of California and now based in the UK, Rachel is a researcher and emerging writer with ME/CFS. Rachel holds a DPhil in anthropology from the University of Oxford (which took her twice as long as it was “meant to”), and she wrote this essay from bed. No matter your story (told or untold), she believes you, and she still believes a better world is possible, too.

I’m sitting in the office of a doctor I found on Zocdoc whose name I can’t remember but was rated highly and accepts Medicaid. The walls are grey, the floors are grey, and through the blinds, I note the sky is overcast, too. I’m somewhere in midtown off the 1-train I took from my parents’ apartment in the Bronx, where I’m spending the year for my doctoral fieldwork. I should be volunteering at the feminist bookstore downtown, the field site for my research, but lately I’ve been struggling to make the commute and back. One day in the city leaves me bedbound for a couple of days, unable to do any work at all. I’ve gotten to know the pullout bed in my parents’ apartment better than the volunteers at the bookstore I’m supposed to—and want to—get to know.

“Well, good news,” the doctor tells me. “Your bloodwork looks normal.”

I sit still, try to collect myself. I feel the familiar contracting of my body. I am practiced in the art of holding it together.

But my body betrays me. I open my mouth in a question, but instead comes a cry. It is not a cry of relief.

***

I’m staring at my face in the bathroom mirror, only it isn’t my face looking back at me. Where my right iris should be—the same shade of denim blue as my mom’s—is nothing but a black blot, not even blue-rimmed. My pupil is fully dilated, unresponsive to light.

When I get to the ER, one parent on each arm, the receptionist sees my eye and her own double in size. I’m immediately whisked away to a triage bed. I’ve been to the ER enough times in New York to know that this isn’t normal. At my sickest—with the virus I never fully recovered from—I was left alone waiting for the doctor, waiting for someone, waiting for anyone, waiting for hours. I was given an IV but made to hold up the saline pouch myself because the hospital had run out of stands. Three hours later, when the doctor finally came to see me, the line had run red, IV bag at my side.

“Well,” the abnormally attentive ER doctor tells me, in his serious but compassionate doctor voice. “It’s either Something, or it’s Nothing.” In the worst scenario, I may have a tumor pressing on my optic nerve and require immediate surgery. But he reassures me he’s on top of it, and I’m rolled down the hall on the gurney for some CT scans.

I’m lucid, and I’m afraid. But lingering underneath the fear, there’s something else, too. Something with wings, fluttering, hopeful.

For once, someone can see that something isn’t right. I don’t have to convince them.

***

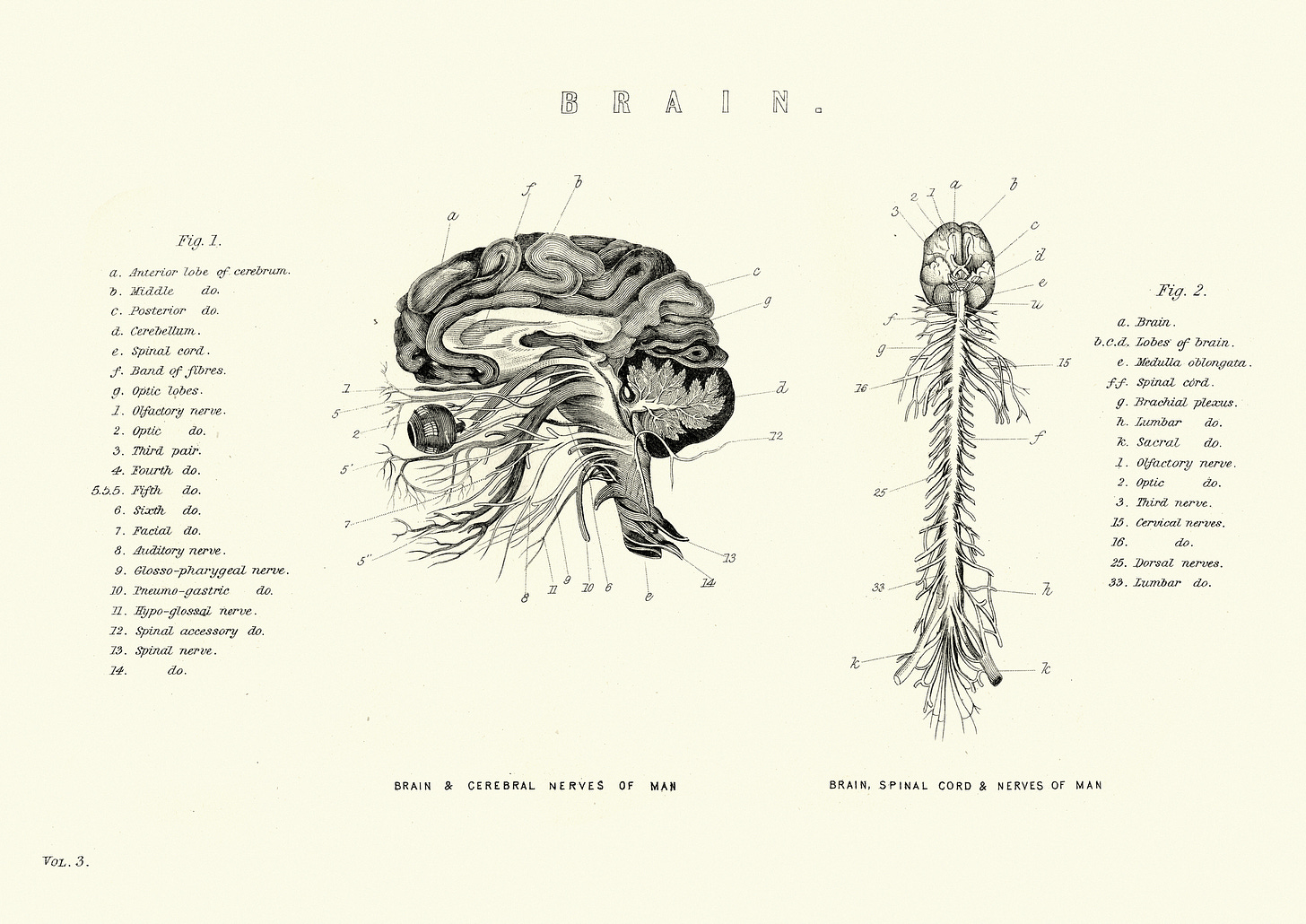

I’m in an Upper West Side office of a neurologist I’ve never met who’s looking at scans of my brain on a computer. The CT scans from the hospital were normal, but she’s click, click, clicking through two-days’ worth of MRIs I had after being discharged from the hospital. My eyes are fixed to her screen, searching for clues, like I know what clues to look for, like the clues I’ve already found aren’t enough. Since my hospital visit, my pupil is more responsive to light but still enlarged and sluggish, unwilling to do what it’s told, not unlike my body most mornings. I don’t mind. It’s the only visible proof I have that my body is misbehaving, and I hold onto it like a testimony, like an alibi.

“I don’t see any signs of multiple sclerosis,” she tells me. I learn that I have a vitamin D deficiency and degenerative disc disease, but the affected discs and nerves don’t correspond to where I experience numbness (on my face, on the left side of my body). The verdict is in, but the findings are inconclusive: the numbness and pupil dilation remain an unsolved mystery. More importantly, so does the main reason I’ve been chasing these tests in the first place: my fatigue.

“Look,” she says. “Doctors like clear-cut answers, ones that fit neatly into a box. And they have a tendency to say nothing is wrong when they can’t find those kinds of answers.

“But just because we can’t find something,” she says, “doesn’t mean nothing is wrong.”

Even though she’s been flicking through images of my brain and my blood cells and my skull and all sorts of insides that even I don’t recognize, it’s with her words that I finally feel seen.

***

“Explain air. Convince a sceptic. Prove it’s there. Prove what can’t be seen,” writes Natasha Brown about racial microaggressions in her debut novel, Assembly. Often, it’s the marginalized who are forced to prove their realities in ways that are visible, digestible, and understandable to the masses, masses who have no interest in evidence that could threaten their worldview or power, let alone who would take someone’s word as evidence anyway. To believe someone without proof, or rather, to take someone’s word as proof, goes against the adage, “seeing is believing.” It is an act of compassion, of solidarity, of defiance, and ultimately, a radical act with transformative capabilities. In the doctor’s office, believing someone at their word can be the fine line between life and death.

Those of us living in the margins, who understand well that hegemonic narratives often hide deeper truths, don’t need to be told to question everything, to probe further, to challenge the stories we’re told. It also feels plainly obvious to say that in an era marked by misinformation, deepfakes, and conspiracies, looking for other sources, or independently verifying the narratives we’re given, is not only the logical thing to do but the responsible one, too.

But what gets to count as evidence?

What happens when your sickness is invisible—not only to passersby on the street, but even to doctors, to blood tests, and most other measures of illness? What can you point to?

How can you make someone believe you?

How can you explain air?

***

I can’t show you my fatigue, but I can show you the Rachel-shaped dent in my bed. I can’t show you my fatigue, but I can show you the photograph where I’m curled up, all three of my cats—my three healers—nuzzled up beside me, notes for exams at my feet. I can’t show you my fatigue, but I can tell you about my dreams, the ones I’ve given up on, and the ones I still hold on to.

I can’t show you my fatigue, but if you believe me, maybe you’ll notice the dent in my bed, the cats curled beside me, the dreams I’ve given up on, and the ones I still hold on to.

Maybe you’ll see me.

***

Susan Sontag, in Illness as Metaphor, writes: “Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick. Although we all prefer to use only the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.”

I find Sontag’s metaphor compelling. But what she doesn’t mention is that you’re not born with both passports. Passports, of course, are issued when someone deems you meet the designated criteria, criteria that you had no part in writing, most likely. When you develop an invisible illness, one that evades healthcare professionals—or should we just call them gatekeepers?—you’re denied the identification that will gain you entry to the kingdom of the sick. Maybe that doesn’t sound so bad at first. As Sontag hints, most of us would prefer only to be citizens of the good place anyway.

Someone else, however, has likely already told you that you’ve overstayed your welcome in the land of the well. After failing to meet deadlines or taking too many sick days, you may have even had your passport revoked.

You may, hypothetically, be told by your doctoral supervisor that you should find someone else to supervise you, because you’re taking too long to finish your degree and he wants to retire. Despite recognizing that you’re struggling to keep up, no one will issue the passport to the other place. The place, you realize, that has what you need: care, community, and compassion.

Somewhere between the kingdom of the well and the kingdom of the sick, you find yourself citizen to none. Instead, you’re some new kind of stateless.

***

During this period where I’m seeing doctors and frequenting hospitals looking for answers about my fatigue (and the pupil and the numbness and the stiff joints and the smorgasbord of unexplained symptoms), I’m doing fieldwork at a feminist bookstore that functions as a safer space for marginalized communities. The mainstream media is having a field day dismissing safe spaces as echo chambers, taking glee in infantilizing those who build them as “snowflakes.” Despite this narrative, I’m determined to show how creative this—and other—safe spaces are, how much room for learning and growth and healing they make.

One day, at a self-defense workshop for people of marginalized genders in the bookshop, I do that thing where I accidentally push my body beyond its limits. I faint. Someone I don’t know pulls up a chair for me. Someone else grabs me a warm chocolate chip cookie and a filter coffee. Later, after canceling a volunteering shift at the bookstore to make a doctor’s appointment, I receive a text from a colleague, and in our exchange, I learn that she, too, has experienced bouts of random unexplained pupil dilation. Another friend from the bookshop checks in and offers a virtual hug.

No one asks for proof that something is wrong with me, or for any type of identification to care for me.

While conducting interviews for my fieldwork, I learn about my peers—other bookshop volunteers, eventgoers, and customers. They tell me about their traumas. Traumas that usually aren’t visible but recognizable when you listen closely, when you give someone space to share, when you don’t ask for proof. Truths you’re trusted with when you extend belief first.

When I ask someone what they think a safe space is, they respond that they’re trying to build an example of a world that doesn’t yet exist. I’m awed by the simplicity and beauty of this framing. Encounters with violence have not diminished their ability to believe in something they cannot yet see–a world built on safety, solidarity, softness.

Suddenly the doctors who hinted, or more than hinted, that believing me without proof would be foolish, irresponsible, negligent, seem so much smaller than before. Held by the words of my interviewee, in this tiny bookstore in this big bad city, I close my eyes to envision this better world, this not-yet world, this world-that-could-be.

I scribble a word in my notebook, underlined three times like a doctor writing her script: visionaries.

***

To live with fatigue is to live with a secret not even you know is true. To live with fatigue is to push your body so you can reveal it as a lie, only to then collapse in bed for days. To live with fatigue is to choose between doing laundry or cooking a meal, then convincing yourself you’re just being lazy. To live with fatigue is an internal tug-of-war, the voices of the non-believers pulling on one side, your body (so shattered, it can barely hold onto the rope) on the other.

Eventually, to live with fatigue is to capitulate, cradle your tired body, and whisper, I believe you.

***

In my case, it is also to be diagnosed, eventually, with chronic fatigue syndrome, by a doctor you’re convinced doesn’t believe the condition is real, who you’re only seeing because you, a grown woman, cried to your GP begging for a referral to his clinic. The doctor who diagnoses you but doesn’t really believe in the diagnosis tells you not to trust patient groups who call the condition ME, and not to trust researchers looking at the connection between fatigue and post-viral illness, even though you told him you’ve been unwell since you were hospitalized with mononucleosis as a teenager. He tells you that you’re not depressed, which you know, because you weren’t coming to him for that, and you know well enough to hide any depressive thoughts so your fatigue isn’t dismissed as psychosomatic.

At least, although he hands it over reluctantly, that coveted passport is now in your hands. It’s not one of the strong passports, one of the recognizable ones that tops the index ratings and can get you almost anywhere. Most people won’t recognize the name, and you’ll still have to fill out extra paperwork to get what you need most of the time, but at least you have something to point to.

When the doctor says not to let your fatigue stop you from doing things, and to accept that you’re going to feel poorly, you put on your best poker face. When he says you should accept that you may fail your degree because you’re not able to keep up with deadlines, you find an online support group for chronically ill students at your university.

You’re able to separate the non-believers from the believers now, so you know not to take his word as gospel. Instead, you limit, as best you can, the activities that leave you bedbound. You get an extension on your degree (and then another), and you call your condition ME/CFS.

***

The story I feel compelled to tell you is one of total triumph, of a completed hero’s journey. In this version of the story, the hero used to treat belief like an unrequited lover, like a small god to chase in the hopes that one day, it would choose her and offer redemption, or revelation. I want to tell you that she nurtured her inner voice until it drowned out the chatter, and that she no longer treats belief as a token that needs to be earned, but instead, a gift she can give to herself freely. What I’m saying is: I want to tell you I am transformed, reformed, recovered.

There is truth in that story. Or at least, it’s a story crawling toward truthfulness, but like most good stories, it’s tethered to fantasy. I still have those days when I question myself, when I push myself too far “just to see,” when I search for visible signs of sickness and rejoice when I find one. To believe my invisible illness is real, or, to believe myself—which it all boils down to in the end—is a choice, and not the kind I made once and then moved on from. If there’s anything I’ve learned, it’s that doubt is a fault line that ruptures at random, unpredictable and capable of knocking you down even when you think you’re in a stable place. Maybe if you choose to believe yourself enough times, belief becomes the baseline, and eventually, you find yourself in new terrain. Somewhere solid, somewhere sure. Or, maybe you just get used to the ground being pulled out from beneath you.

Lately I’ve been wondering what it means to lead with belief in times like these. I imagine, even if you’re reading these words weeks, months, or years after I’ve written them, whether you’re near to me or far, you’ll know what I mean by “times like these.” Open the news and you’ll find stories of endings—endings of people, of places, of planet. What does it mean to believe in a world we cannot see—a freer one, a truer one—in times like these? How do we believe in something better when evidence suggests we should just give up now?

The impulse of my internal optimist wants to share some kind of slogan about willing the world we want into existence, while the realist in me knows that conviction falters even in the most hopeful among us. So, in lieu of a motivational platitude, let me say this: that I recently went to a protest, and although the crowd started small, it grew as passersby joined in, buoyed by seeing others in action and giving hope to those of us already marching. Let me say that at the end of the protest, strangers clasped hands and danced, and as the sky greyed above us, I understood what it means to be held in darkness. Let me say that after a recent ME/CFS flare, I read a magazine by sick and disabled writers, and I felt seen and heard by people I don’t know and may never meet but who know me anyway.

What I’m saying is, when it feels too shaky to lead with belief on your own, who might you hold onto so that the ground beneath you feels a little more secure, a little more real?

What I’m saying is, maybe the antidote to doubt isn’t belief, but love.

| A guest post by

|