Are We Forcing Our Pets to Live Too Long?

Length: • 14 mins

Annotated by Mark Isero

Some content could not be imported from the original document. View content ↗

The cat was named Pablo and looked like a million others. A sweet-faced tabby, grayish, white bib, white socks, green eyes. Andrzej Kinczyk and his partner ended up with him after their roommate moved to Europe and left Pablo behind with them in Queens. Kinczyk will tell you that he was “just a regular street cat.” He’ll also tell you he was “the most beautiful cat, very independent, a very cool guy.” Needless to say, they fell for him. When they had guests over, Pablo would sashay into the middle of the room to solicit the attention he was owed. The couple doted on him, worried over him, and adopted another cat partly to keep him company. For years, Pablo seemed at ease. Then, when he was eight, the vet found a lump in his belly.

When Kinczyk and his partner learned the lump was a tumor, they crossed into a new world — from the one where Pablo’s biggest problem was the occasional UTI to the one where his body posed questions they couldn’t answer. Like: Can you afford to keep me alive? They decided to try. Pablo had high-grade lymphoma, an aggressive form of the disease, but there were things they could do — and they did them. Pablo had surgery, then six months of chemotherapy, then three years in remission. When it came back, he got another six months of chemo. The initial round made Pablo nauseated. The second made him lose his whiskers. Kinczyk gave Pablo supplements to manage the nausea, and his whiskers eventually grew back. Even so, Kinczyk sometimes wondered what they were doing. “The thing that helped us make the decision was that he seemed to be having a nice life between treatments,” he says. “But still, to be pumping more of that stuff into this cat, we started to ask, ‘Are we helping him, really, or doing it for ourselves?’ ”

Round three was the worst. It had been five years since Pablo was diagnosed. The doctors put him through another round of chemo, and over the months the cancer seemed to shrink — but something else was wrong. His blood work looked bad in a new way. The vets offered transfusions, which, to Kinczyk, seemed crazy. For the first time, Pablo lost his appetite; for the first time, his owners seriously discussed euthanasia. They made the appointment. But the day before they were to take him, Pablo died at home. Over six years, Kinczyk estimates that he and his partner spent $30,000 keeping Pablo alive. “The biggest regret is not that we did the chemo at all but that we waited too long to put him down,” says Kinczyk.

This is the part of your pet’s life you do not want to consider: the part when it has to end. Sometimes, the decision will be made for you by an accident or crisis, when the obvious kindest thing is to end the suffering faster; sometimes, you simply can’t afford the treatments that would help them. Other times, the decline is long and slow and, increasingly, we’re part of the reason why. As advanced veterinary medicine proliferates — along with the more recent addition of pet hospice and palliative care — new ways to care for our pets sit uncomfortably with the knowledge that we can euthanize them at any time. This opens up an ambiguity we aren’t equipped for. Beyond the hospital bills and appointments, the guilt and the grief, the downward slope of our pet’s life reveals the gulf between us. We don’t know what they’re feeling. We don’t know what they want or understand. The relationship is intimate, but their pain can feel foreign. We idle in the bargaining phase: What do you want? What can I do? Although we bend our lives to them — increasingly in this country we do — we are the ones who hold the power. To be happy about that, we convince ourselves that our pets like the lives we have chosen for them. Sometimes, we convince ourselves that they would want those lives to last forever. But what if they need them to stop?

We have always killed our pets. There was a time when you wouldn’t even have considered trying to keep a sick or unwanted cat or dog alive. If you didn’t drop a sack of kittens in the river, you might take them to a shelter or vet at the first sign of inconvenience. The late philosopher Bernard Rollin, who founded the veterinary medical-ethics course at Colorado State, wrote that, in the 1960s, he knew people who put their dog down before a vacation to save on kennel fees. By the 1980s, doing this would seem anathema to many. Pets became a part of the family — one theory is that this is because Americans were staying single and bonding with their dog instead of their 1.9 children. Animal medicine grew and specialized with veterinary colleges opening around the country and separate tracks developing for fields such as oncology. Suddenly, when your pet was sick, your neighborhood vet could present you with options and referrals.

So now you’re buying insulin for your schnauzer. Taking your pit bull in for allergy shots and treating your cat’s kidneys with supplements. Needless to say, you may not be able to afford this, not when insulin alone can run hundreds of dollars a month and chemo costs upwards of $10,000; even if you had the foresight to sign up for pet insurance, not every treatment will be covered — and if your animal is already sick, good luck getting covered at all. (A lot of plans exclude preexisting conditions.) That you can, with enough money, ease your pet’s symptoms is a beautiful thing. But all the money in the world can’t save you from the fact that your cat or dog will still reach a stage of life called dying and it’s up to you to recognize it.

You may know euthanasia is considered humane for sick or old pets and that dragging them to a natural death is not. The veterinary logic is that since we can end suffering sooner, we should. While not everyone believes in it, for reasons religious or personal, the American Veterinary Medical Association treats euthanasia as standard. The AVMA’s guidelines reiterate what vets have believed for decades: “Prima facie, it is the ethical responsibility of veterinarians to direct animal owners toward euthanasia as a compassionate treatment option when the alternative is prolonged and unrelenting suffering.” (They also acknowledge that vets and their staff will “struggle with the ethics of the caring-killing paradox.”) The current preference is for the cat or dog to receive a sedative first so they’re unconscious when the vet injects them with a lethal dose of barbiturates. The goal is fast and painless, and the process almost always is. There are rare cases when an animal will react badly to the sedative and freak out. This is horrible for all involved.

The abrupt shift from extending a pet’s life to ending it is one pet owners struggle to make — and so, as the veterinarian Dr. Dani McVety says, they “wait and wait and wait and wait.” McVety, who is based in Tampa and runs a home hospice and euthanasia business called Lap of Love, guesses most veterinarians would tell you that, “ten to one,” they’re asked to euthanize animals that have been forced to hold on too long rather than those the vet doesn’t think should be euthanized. One veterinary technician tells me some of her colleagues refuse to work at hospitals that offer internal medicine or oncology; they fear that if those treatments are available, they’ll end up seeing more pets whose owners just need to put them down.

It is widely believed that a cat or dog lives in an eternal present. As far as they’re concerned, how they feel now is how they will always feel. They’re not optimistic. They’re not pessimistic. If they appear stoic, it’s not from shame or pride. They’re not trying to spare you their suffering; you’re simply unable to see it. A vet can. “Dogs and cats don’t hide their pain,” says McVety. “They just don’t have an emotional reaction to it.” Although we may know that a painful treatment could benefit a dog in the future, it’s unclear if the dog itself knows what “the future” is. “That’s the best part about them: that they’re living in the moment,” says Daniela Doyne, a veterinary technician based in the Bay Area. “They are the prime example of what mindful meditation is trying to achieve. When they die, they’re not going, I really wish I could have seen Grandma and Grandpa one more time.”

The routines of care train your body. You open the door with caution so your cat will not escape. You kneel to refill the food bowl. You’re so used to this you can do it in your sleep, stumbling out for the morning walk before your brain powers on. You learn your animal physically: If I do X, my animal does Y. If I forget to do A, my animal will do B. Most of us understand so little about the logic of our pets’ preferences that we approach them with a kind of superstition. So the first sign that they are unwell hits you like a trick of the light — you hadn’t known how much you anticipated their habits and movements until one day you do X and your animal does Z instead. Cats may show they’re sick by doing something that’s easy to ignore: They will simply hide. One woman tells me her senile terrier began wandering in circles around the house. The changes can come on slowly, making it hard to see a progression. Paranoia sets in. Self-doubt blooms.

The less experience you have with animal death, the deeper in denial about your pet’s condition you tend to be. When McVety provides hospice treatment, she’s there both to help you manage your pet’s pain and to give you a dose of reality. Sometimes when she asks clients whose dogs have congestive heart failure what they picture for their pet’s last moments, they’ll say they envision saying good-bye with the whole family gathered around. The only catch is they want to wait for their husband to get back from his business trip, and that won’t be till next week. “So I’ll say, ‘Are you okay coming home to find that the dog’s passed away by himself?’ And if they say that would be great, I say, ‘Well, remember, you won’t know if he was in pain for an hour before he finally died. You don’t know if he was screaming.’ I’ve had clients call me and they’ve come home and the dog is on its side, bleeding out of its nose or mouth.” She estimates that 30 to 50 percent of her practice’s hospice appointments become euthanasia appointments on the spot.

McVety says that people in their 30s and 40s, who may be making this decision on their own for the first time, almost always wait too long. Doyne, the vet tech, works at an urgent care and has heard every rationale from clients for keeping very sick animals alive. She counts them off: “ ‘Well, he’s still eating’ — that’s my favorite one because really what they mean is that they’re force-feeding him one to two tablespoons of food once a day. ‘He’s still wagging his tail.’ Yeah? They do that because they like being with us. Or ‘He’s looking a little skinny,’ and the animal is emaciated. ‘He’s a little lethargic’ — and then we get the animal and he’s open-mouth-breathing on his side.”

Sometimes, if McVety thinks the client can handle it, she’ll give it to them straight: “I would’ve done it last week.” Still, your vet is unlikely to make the euthanasia decision for you. This is a product of their emotional intelligence, not a legal mandate. They do know you want someone to give you permission. Dr. Wendy McCulloch, a veterinarian who does in-home treatment and euthanasia in New York City, says, “The classic case would be turning up to see the dog is in diapers, in a semi-comatose state, lying in stains, and unable to move. And the owners are asking you, ‘Do you think it’s time?’ ” She recalls one appointment at a home where a family had a 16-year-old shepherd. The dog was incontinent and could no longer walk. “When I get there, I think what I’m going to be doing is confirming the situation — that everyone else is onboard,” she says. “Sure enough, I get there and the dog’s definitely done. And the family asks, ‘So you think it’s time, then?’ And I just say, ‘Yep.’ They all burst out laughing. They just needed someone to say it.”

Still, even veterinarians can struggle to make the decision themselves. Dr. Michael S. Kent, a professor of radiation oncology and co-director of the Comparative Cancer Center at UC Davis, tells me a story about his partner’s late rescue dog, Caesar. One day, Caesar didn’t get up to greet him when he got home. Probing Caesar’s belly, Kent could feel something amiss, and he and his partner decided together that if they got him scanned and found any other masses, they wouldn’t put him through the torture of treatment; they would say good-bye while he was under. But then, “we found two small nodules in his lung and a large mass on his spleen,” Kent says. “And we were both like, ‘No, he’ll go to surgery.’ We said that instantly without talking to one another — even though ahead of time, clinically, we had decided we would stop.” Caesar lived another four years. “And that’s great,” Kent adds, “but that tells me I didn’t actually know what I’d do in that situation.”

McCulloch recently let go of her beloved cat, Chance, after six years of cancer treatment. She’s from New Zealand, and whenever she spoke to people back home about her cat’s illness, they would say, “You’re crazy, you Americans and your animals!” As she hesitated over a final decision, she started to wonder if that was true. “To be honest, I think I left it too long,” she says. “Academically, I knew it was the right time to put him to sleep. It wasn’t until I had a friend who’s kind of dogmatic tell me, ‘Put the poor cat to sleep!’ that I snapped out of it.” She has a deeper appreciation for her clients’ confusion. “It’s hard when you live by yourself, as many people do in New York City, and your pet appears as a little sanctuary when you come home,” she says.

Pet owners kept telling me they regretted holding out. “It was selfish for me to wait,” says a friend whose sweet brindle mutt went into kidney failure at age four. She first noticed the dog was sick when he couldn’t get warm again after playing in the snow, shivering and refusing his food. The vet couldn’t figure out what had happened — maybe Lyme disease, maybe something else. In a strange way, mystery led to hope. My friend wanted to try. Since she couldn’t afford treatment, she held a fundraiser. She got the money and took her dog to the doctor, but he didn’t get better. Not until the vets started talking about feeding tubes did she realize how far she had gone. She made an appointment. She now believes she was in denial. “He didn’t need to have those last couple of weeks just so I could wrap my head around the idea that I was gonna have to kill him,” she says.

Even when you know what you need to do, you may find yourself navigating a hostile system. As more private veterinary clinics are taken over by private-equity firms and corporations, vets working at those clinics have reported being asked to push treatments in order to make more money. When Darlene Kaplan brought her senior Norwich terrier, Dylan, to be euthanized at a midtown animal hospital — which happens to be part of a chain of corporate vet hospitals across the country — she was under no illusions that he could get better. Kaplan is in her 60s and has had enough dogs to fill a cabinet with their urns. Dylan had been declining for a year and that evening had begun to wail in a way she had never heard before. But at the hospital, she found herself confronting a young-looking veterinarian who told her that her dog’s yearlong slide into dementia might “pass” and suggested bringing him home and medicating. When Kaplan protested that Dylan was already medicated and, besides, had been confused and walking in circles for months, the vet seized on that. She said it could be an ear issue and recommended an ear cleaning. “She just kept pushing, and I was getting really upset,” says Kaplan. “After eight dogs, you know what’s going on.” Finally, Kaplan collected Dylan and left. One of the people working at the front desk quietly gave her the number of a different emergency clinic downtown where she could have Dylan euthanized.

The year I turned 29, my cat started shitting in a new and upsetting way. She was not that kind of cat. In fact, I was proud of this: She didn’t miss the litter box, she didn’t throw up, she didn’t eat plants. She was tidy and social and funny and unruly. I was 19 when I adopted her and so unformed that she quickly came to feel like a part of my own body. The last year of her life, she learned a new trick: When I bent down to fill her bowl or pick something up off the floor, she would hop up on my back and purr madly. I loved her so much that sometimes, when she crawled into my bed to spoon me, I would cry just from feeling her trust. So when she started defecating erratically around the apartment, I know I must have taken her to the vet right away. I hope I did. I want to believe I would have acted fast.

It was unclear to both me and the vet why she was doing it. My roommate had a cat, whom my cat disdained. (Revenge?) It was the dead of summer, and the top-floor apartment was boiling. (Dehydration?) She had just turned ten. (New allergies?) I switched out the food; I freshened up the water and bought another fan. It seemed okay for a while, then it wasn’t. She was distressed. I brought her to the vet again. And again. Then another vet. I was skipping work. By the time they found the cancer, it was too late: It had spread throughout her body. Even with chemo, which I couldn’t afford, she wouldn’t stand a chance. Or at least that’s how I have chosen to remember what they told me. I’d already scraped out my savings account trying to learn what was wrong. I clung to those vet bills as if they proved something — my action, my devotion, my love.

They told me I would know when it was time, but in the last days of her life, any time would have been the right one. I just couldn’t bear to choose until the afternoon when she could no longer do more than huddle in place, eyes downcast, the ringed tip of her black-and-white tail tucked under her orange body. The whole shape of her said pain. I made the appointment. I stayed in the room while they gave the injections, my hands resting on her body, and felt her pulse stop. Walking down the street after leaving the clinic, I imagined I saw her running up the sidewalk before me.

That night, and for many nights after, my mind churned backward, searching our decade together for any time I might have exposed her to something toxic and cancer-causing. I could’ve done better; I should’ve done better. And then there was the loneliness of being without her and truly unattached for the first time in adult life. I felt I had lost a part of my identity.

No loss happens in a vacuum. If cats and dogs don’t have an emotional response to pain, we’re the opposite. “These animals mean something to these people that I can never understand,” says McVety. “I’ve worked with people whose child committed suicide, and this dog is the last thing they have left. Or the cat is the only thing they have left of a sister, or parents, or spouses who have died.” At the end, cleaving your narrative from your animal’s could be the last, best way to take care of them. Every time is different, yet every time is the same. McVety notes, for example, that the people who wait too long the first time never wait so long again. And nearly everyone tells her the same thing: At some point in the euthanasia appointment, as they’re preparing to say good-bye to their pet, the client will turn to her, full of gratitude, and say, “I wish we could do this for humans.”

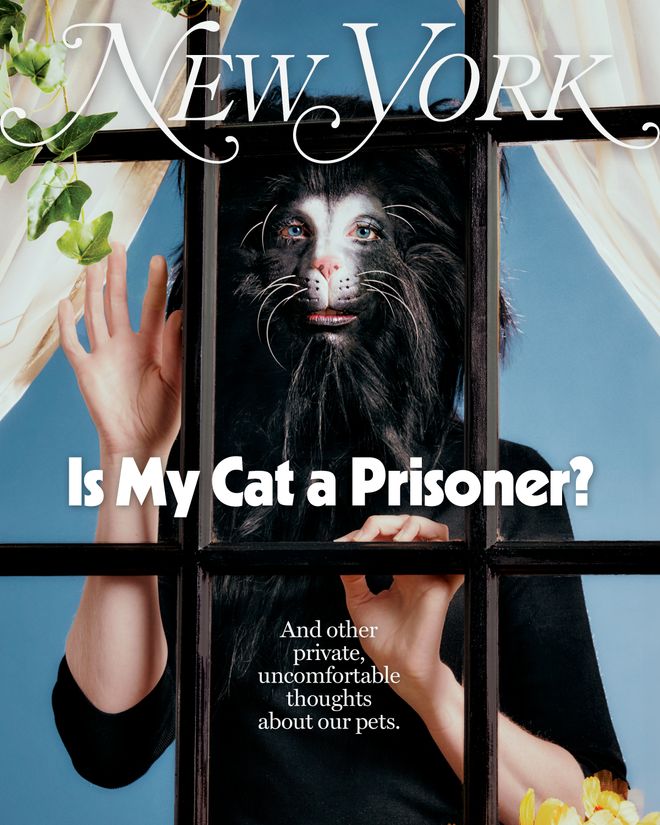

Is My Cat a Prisoner? And other ethical questions about pets like ...

➭ Am I a Terrible Pet Parent?

➭ Why Did I Stop Loving My Cat When I Had a Baby?

➭ What Do Vets Really Think About Us and Our Pets?

➭ I Am Not My Animal’s Owner. So What Am I?

➭ Was I Capable of Killing My Cat for Bad Behavior?

➭ Should I Give My Terrier ‘Experiences’?

➭ Is There Such a Thing As a Good Fishbowl?

➭ Do Runaway Dogs Deserve to Be Free?

➭ Are We Lying to Ourselves About Emotional-Support Animals?

➭ Does My Dog Hate Bushwick?

➭ How Agonizing Is It to Be a Pug?