#307 ‒ Exercise for aging people: where to begin, and how to minimize risk while maximizing potential | Peter Attia, M.D.

Length: • 57 mins

Annotated by Conner

In this special episode, Peter addresses the common questions about starting or returning to an exercise routine over the age of 50. Individuals in this age group have frequently reached out with questions about whether it’s too late to start exercising and often express concern over a lack of prior training, a fear of injury, or uncertainty about where to begin. Peter delves into the importance of fitness for older adults, examining all four pillars of exercise, and provides practical advice on how to start exercising safely, minimize injury risk, and maximize potential benefits. Although this conversation focuses on people in the “older” age category, it also applies to anyone of any age who is deconditioned and looking to ease into regular exercise.

Subscribe on: APPLE PODCASTS | RSS | GOOGLE | OVERCAST | STITCHER

Some content could not be imported from the original document. View content ↗

We discuss:

- Key points about starting exercise as an older adult [2:45];

- Why it’s never too late to begin exercising and incorporating the four pillars of pillars of exercise [5:45];

- The gradual, then sharp, decline in muscle mass and activity level that occur with age [10:00];

- The decline of VO2 max that occurs with age [15:30];

- Starting a training program: exercise variability, movement quality, realistic goals, and more [18:30];

- Improving aerobic capacity: the malleability of the system, the importance of consistency, and setting long-term fitness goals [25:15];

- Starting cardio training: base building, starting with low volume, and zone 2 training [30:45];

- The critical role of Vo2 max in longevity [36:45];

- How to introduce VO2 max training to older or deconditioned individuals [46:15];

- Options for performing zone 2 and VO2 max training [53:45];

- The ability to make gains in strength and muscle mass as we age [57:00];

- How to implement strength training for older individuals [1:01:00];

- Advice for avoiding injury when strength training [1:07:30];

- Risk of falls: the devastating consequences and the factors that increase fall risk [1:12:15];

- Mitigating fall risk: the importance of foot and lower leg strength, ankle mobility, and balance [1:19:45];

- Improving bone mineral density through resistance training [1:24:30];

- The importance of protein in stimulating muscle protein synthesis, especially in older adults [1:31:00];

- Parting advice from Peter [1:34:00]; and

- More.

Episodes

Now playing

Details

Zone 2 training: impact on longevity and mitochondrial function, how to dose frequency and duration, and more | Iñigo San-Millán, Ph.D. (#201 rebroadcast)

#306 - AMA #60: preventing cognitive decline, nutrition myths, lowering blood glucose, apoB, and blood pressure, and more

#302 - Confronting a metabolic epidemic: understanding liver health and how to prevent, diagnose, and manage liver disease | Julia Wattacheril, M.D., M.P.H.

View the Show Notes Page for This Episode

Become a Member to Receive Exclusive Content

Sign Up to Receive Peter’s Weekly Newsletter

Iñigo San-Millán is an internationally renowned applied physiologist and a previous guest on The Drive. His research and clinical work focuses on exercise-related metabolism, metabolic health, diabetes, cancer metabolism, nutrition, sports performance, and critical care. In this episode, Iñigo describes how his work with Tour de France winner Tadej Pogačar has provided insights into the amazing potential of elite athletes from a performance and metabolic perspective. He speaks specifically about lactate levels, fat oxidation, how carbohydrates in food can affect our lactate and how equal lactate outputs between an athlete and a metabolically unhealthy individual can mean different things. Next, he discusses how Zone 2 training boosts mitochondrial function and impacts longevity. He explains the different metrics for assessing one’s Zone 2 threshold and describes the optimal dose, frequency, duration, and type of exercise for Zone 2. Additionally, he offers his thoughts on how to incorporate high intensity training (Zone 5) to optimize health, as well as the potential of metformin and NAD to boost mitochondrial health. Finally, he discusses insights he’s gathered from studying the mitochondria of long COVID patients in the ICU.

We discuss:

The amazing potential of cyclist Tadej Pogačar [2:00]; Metrics for assessing athletic performance in cyclists and how that impacts race strategy [7:30]; The impact of performance-enhancing drugs and the potential for transparency into athletes’ data during competition [16:15]; Tadej Pogačar’s race strategy and mindset at the Tour de France [23:15]; Defining Zone 2, fat oxidation, and how they are measured [26:00]; Using fat and carbohydrate utilization to calculate the mitochondrial function and metabolic flexibility [35:00]; Lactate levels and fat oxidation as it relates to Zone 2 exercise [39:15]; How moderately active individuals should train to improve metabolic function and maximize mitochondrial performance [51:00]; Bioenergetics of the cell and what is different in elite athletes [56:30]; How the level of carbohydrate in the diet and ketogenic diets affects fuel utilization and power output during exercise [1:07:45]; Glutamine as a source for making glycogen—insights from studying the altered metabolism of ICU patients [1:14:15]; How exercise mobilizes glucose transporters—an important factor in diabetic patients [1:20:15]; Metrics for finding Zone 2 threshold—lactate, heart rate, and more [1:24:00]; Optimal Zone 2 training: dose, frequency, duration, and type of exercise [1:40:30]; How to incorporate high intensity training (Zone 5) to increase VO2 max and optimize fitness [1:50:30]; Compounding benefits of Zone 2 exercise and how we can improve metabolic health into old age [2:01:00]; The effects of metformin, NAD, and supplements on mitochondrial function [2:04:30]; The role of lactate and exercise in cancer [2:12:45]; How assessing metabolic parameters in long COVID patients provides insights into this disease [2:18:30]; The advantages of using cellular surrogates of metabolism instead of VO2 max for prescribing exercise [2:25:00]; Metabolomics reveals how cellular metabolism is altered in sedentary individuals [2:33:00]; Cellular changes in the metabolism of people with diabetes and metabolic syndrome [2:38:30]; and More.

Connect With Peter on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook and YouTube

Show Notes

*Notes from intro:

- This is a special episode of The Drive

- It’s like an AMA where Peter is the one answering the questions

- However, this episode will be available to all

- One of the most common questions that we receive through the site is from people who are “older”

- We’ll define that as 50 and up

- People who realize the importance of exercise, but are wondering if it’s too late for them to start

- This could be because they’ve never trained

- Or they’re worried about injury

- They have no idea how or where to start

- Or they used to exercise when they were young, but they’ve kind of got away from it and they’re just trying to figure out what to do

- We wanted to create an episode for these people: people above 50 who haven’t been exercising (at least recently), who want to start but don’t know where to begin

- In this episode, we speak about exercising in that age range as it relates to all 4 pillars of exercise and dive into

- Why it is not too late

- What one can do to start exercising

- Minimize injury risk

- Maximize potential

- This conversation will be a little less technical than some of our AMAs

- Peter wanted to try to keep it a bit more conversational, as if Peter were answering patient questions

- What we’ve done to accommodate that is included many of the studies that support the observations and points that are being made in the show notes

- Even if you’re not in this “older”/ 50 and up age category, most of you likely know someone who is like a parent, and you may find this, hopefully something that you can share with them and help them to start exercising

- Although much of what we’ll talk about applies to anyone in the “older” age category, it also can apply to anyone of any age who is deconditioned and looking to start slow

Key points about starting exercise as an older adult [2:45]

About this episode:

- This episode is designed like an AMA but available to everyone.

- It addresses common questions from people aged 50+ about starting exercise.

- Aimed at those who haven’t trained before, worry about injuries, or think it’s too late to make a difference.

- Although the focus is on people aged 50+, the advice applies to anyone deconditioned and looking to start exercising.

- Younger listeners can share this episode with their older parents to encourage them to start exercising.

- This conversation is intended to mimic how Peter would speak to his patients.

Key Points on starting exercise as an older adult:

- Peter is himself in the over 50 camp

- And 50 is a significant turning point for starting exercise, but another crucial point is 65+.

- At 65+, people typically experience noticeable reductions in strength and vestibular changes, which increase the risk of falling.

- The episode will address concerns specific to the 60-65 age group and emphasize the importance of being mindful of these changes.

- Recommendations will cater to the unique needs of older, untrained individuals to help them start exercising safely and effectively.

Why it’s never too late to begin exercising and incorporating the four pillars of pillars of exercise [5:45]

What do you say to the person who asks, “Is it too late for me to start doing this? Is it too late for me to worry about this and start making changes?”?

- Peter has spoken at length about the importance of exercise for longevity

- He’s had the same response largely for many years now

- Some people will have already heard him say this on another podcast, but truthfully I haven’t come up with a better analogy yet

The analogy of saving for retirement

- So if you could be talking to somebody who’s in high school or college and you were talking to them through the lens of being a financial advisor, their fiduciary, what would you say?

- You would say, “Listen, there’s this really magical thing called compounding that Einstein basically said was the 8th wonder of the world. And you want to use it to maximum advantage.”

- To do that, you should start saving immediately

- When you get your first job, you should be saving

- If not, certainly by the time you get out of college, you should be saving

- And if you do that, you don’t really have to be that brilliant about it

- If you put all of your savings into an index fund at the age of 22, the probability that you are not going to be set when you retire is so low

- But what happens if you’re talking to somebody who’s 45 and due to life circumstances they just haven’t been able to save

- They haven’t made enough money to even have some disposable saving income

- Or they’ve saved and lost or invested badly or something like that

- Would you say, “Well, too bad?” No, of course you wouldn’t

The point here is it is never too late to start saving for retirement, but you must understand something which is the longer you wait to start, the more you’re likely going to have to save, the greater return you’re going to need, and therefore probably the greater risk you’re going to take

“It’s never too late to start saving and it’s never too late to start exercising. But I want the message to be ‘Don’t wait’”‒ Peter Attia

- Peter wants the message to be: don’t wait because of some reason and say, “Well, I’m going to wait till I’m older because...”

Remind people of your 4 pillars and how you think about each of those pillars individually as someone is aging?

- It’s basically stability, strength, aerobic efficiency [zone 2], and peak aerobic output [zone 5]

- You could argue, “Well, those are just kind of a continuum.”

- Peter would say “Sure, but let’s not get lost in the semantics. Those things, if you define them the way I do, kind of constitute everything.”

- Stability is kind of a broad term, but embedded within stability is everything that enables you to dissipate force safely

- Everything that enables you to have balance and flexibility because believe it or not, those come from stability

- If you have balance by definition, you have stability

- You can’t have balance without stability, you can’t actually have flexibility without stability

We think of training as having a purpose, and different types of training factor into these different activities

- There are some types of training that myopically hit 1 of these things

- If you’re riding a bike (like Peter does for zone 2 training), it is a very one-dimensional activity

- There are no degrees of freedom outside of you pedaling the crank

- And if you do it at a fixed power output that meets the criteria for zone 2, then you’re very narrowly targeting that

- You’re doing very little for any of the other systems

- Conversely, there are other types of training like rucking with a heavy weight on hills, you’re actually targeting all 4 of those elements

- That requires tremendous stability, moments of strength, large segments of aerobic base or aerobic efficiency, and moments of peak aerobic output and even anaerobic output

- That’s just something to keep in mind

The gradual, then sharp, decline in muscle mass and activity level that occur with age [10:00]

A few graphs Peter thinks are important

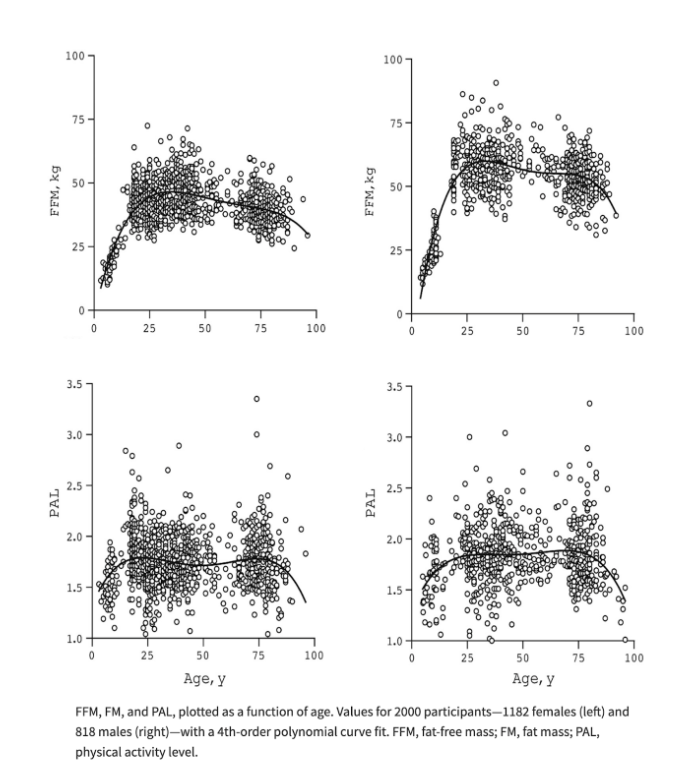

Figure 1. Fat-free mass (FFM) and physical activity level (PAL) throughout life in females (left) and males (right). Image credit: The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2021

- This is a figure that Peter fought like crazy to include in Outlive, and he got overruled and just kicked in the groin

- So it really makes Peter happy to be able to show this figure here

- This figure is basically 4 graphs (2 of them are for men, 2 of them are for women)

- 2 of them demonstrate fat-free mass, which is a great proxy for muscle mass

- 2 of them show spontaneous or deliberate physical activity

- And then each of these has an X-axis that shows age

- In that sense, you can think of it as a 2-by-2 male-by-female versus activity and fat-free mass

Peter points out 4 observations

- 1 – Notice that fat-free mass rises up, ie. lean mass rises pretty significantly from birth till about the age of 25, and then it slowly starts to go down

- This is true for males and females

- You’ll notice that from age 25 to 75, there is indeed a gradual reduction of lean mass

- 2 – Something happens at the age of 75, which is the fall-off in lean mass becomes much more significant

- It’s actually even more noticeable in men, presumably because they’re starting from a higher baseline

- 3 – This is clearly a curve that has 3 segments:

- 1 – birth to 25 where you’re gaining, gaining, gaining

- 2 – 25 to 75 where you’re slowly losing

- BTW, we know the numbers: loss of fat-free mass is happening at 8-10% per year

- 3 – 75 and on is where you fall off a cliff

- 4 – The lower figures show physical activity level, and you can see that a very similar trend occurs

- It tends to peak a little bit earlier in late teens and early 20s

- Interestingly, it doesn’t have a huge fall-off between the ages of roughly 20 and 75 (it stays relatively constant)

- If anything, it probably dips a touch in middle age that might have to do when we’re at sort of peak work and therefore not as busy physically

- But again, you notice what happens at the age of 75: physical activity level drops like a stone

- Peter adds, “This begs the age-old question, ‘Which is the chicken and which is the egg?’”

- Because again, there is an unmistakable relationship here between physical activity and muscle mass and age, and something very noticeable happens at the age of 75

Data like these cannot give us causality, in other words, can’t tell us which one’s causing the other, but anybody who’s observed people at this age would come to the conclusion that there is bidirectional causality here

- In other words, as we lose muscle mass, we become less active

- And as we become less active, we lose muscle mass

This next point came from a very recent interview Peter did with Luc Van Loon

- Luc made a very interesting point about data like these

- We’re replete with these sorts of data that show population-based reductions in activity of aging individuals always make it look like it’s kind of a gradual continuous curve

- Even if it happens precipitously, it’s still a continuous curve

- Luc pointed out that it’s true at the population level, but it’s not true at the individual level

- We’re replete with these sorts of data that show population-based reductions in activity of aging individuals always make it look like it’s kind of a gradual continuous curve

- At the individual level, it is a series of big discrete drops

- And so when you smooth out thousands of people with big discrete drops, it looks like a smooth drop

What it really comes down to is once you reach a certain age, even minor setbacks become permanent setbacks

- We’re going to talk about that, but we have to be able to avoid that situation

One example

- People have long heard Peter talk about the idea that once you reach a certain age (like 65), and if you fall and break your hip or femur, the probability of death is really high

- It’s in the order of 15-30%

- What often gets forgotten there, even though Peter always tries to mention it, is of the survivors (meaning the people who don’t go on to die within 12 months), 50% of those people never reach the same level of function again

- That’s an example of why these curves are probably not smooth, but in fact have these discrete step-offs

The decline of VO2 max that occurs with age [15:30]

Talk in the same way about how you talked with the muscle and activity decline by looking at VO2 max

Figure 2. VO2 max by age in women and men. Data from: JAMA 2018

- This table shows exactly what is happening to VO2 max as we age

- The purpose of this table is to show you something else: the quartiles of VO2 max by age

- The way this table is broken up is that low, below average, above average, and then high and elite combined represent the 4 quartiles of VO2 max

- The difference is that the elite group peels off the top 2.3% for each respective age and sex

A more important point is to give you a sense of how every one of these categories of VO2 max falls [with increasing age]

The elite categories are most illustrative (these are the top 2.3% of the population)

- For example, if you look at a woman in her late teens, the top 2.3% would have a VO2 max greater than 53 mL of oxygen/ kg/ minute, and you can see that that will fall such that by the time a woman is 80, to be in the top 2.3%, she would have to be greater than 30 mL/kg/min

- What’s interesting is that a VO2 max of 30 places her in the bottom quartile for the late teens

- It would place her at about the 25th percentile for someone in her 20s

The implication here is that regardless of how fit you are, you can still expect to see a precipitous drop in VO2 max

Peter has talked about this many times: if your aspiration is to be able to do what you want without limitation in your final decade of life, you need to have a VO2 max that is 2 decades younger at the elite level

- Certainly his patients are probably very sick of hearing this

- This means if you want to climb a flight of stairs, carry luggage up a broken escalator, go for a hike at age 90

Starting a training program: exercise variability, movement quality, realistic goals, and more [18:30]

What are the most important aspects of training if you’re starting or even returning to exercise in later life?

- This could be for people who have never exercised

- Or this could be for people who exercised all the way until they were 40, but then got busy with family life etc. and took 10, 15, 20 years off, and now they want to get back into it

The principles of exercise variability and movement quality will always trump volume, load, and intensity

- Most people listening would agree that that’s an obvious statement to make for someone who’s new to the game

- But this is an example of something where that’s even true for someone like Peter

- He has a very high training age

- That’s the term that we use when we’re assessing patients to understand how much volume they’ve done and over what period of time

- With the exception of 1 very bad injury, he has had zero interruptions in very high volume of training since the age of 13

- Yet as he is now in his 50s, he realizes he need to be much more attentive to these principles of exercise variability and movement quality

- The reason is quite simply he’s much more prone to injury today than he was before

- He has a very high training age

- Peter has to think of ways to challenge himself that are not just load dependent

- That doesn’t mean that he doesn’t still push load in complex movements like a deadlift (he does), but he’s clearly not going to do nearly as much load or volume

- He’s going to want to challenge himself

- And by saying this of himself, what he’s really saying is everybody should be thinking about this, especially at this age, in terms of circuit training exercises where you are doing more than 1 thing at a time

An example of this might be that for someone just starting out to do more body weight exercises that are slightly more complex movements

Another exercise

- A step-back lunge is an important thing for them to be doing, even if it’s just body weight versus just working on a leg press with heavy weight

- There’s a time and a place for using machines (we’ll come back to this)

- They are a very good thing for someone starting out because they control the range of motion, but we must be able to mix that in with more complex movements that are variable in more than one plane

- For those movements, we obviously want to de-load them so that we just begin to do the neuromuscular training

For the person just taking that first step to exercise, how are you going to think about the structure of the programming that you give them?

- It always starts with a question that is obvious but sometimes overlooked

- This is something even Peter overlooked a lot years ago

You have to come up with something that is realistic for a person ‒ you want them to look back in 3 months and view this as a positive experience

- If in 3 months, they’ve improved by every objective metric and they hated it or they’re injured, it’s not a success

- People are going to be very different in terms of what their appetite for beginning is

- Remember, we’re focusing this discussion on people who are not lifelong exercisers and therefore by definition, they’re either starting from scratch or maybe coming back to it after a long hiatus, and you have to assume that their appetite for training is not going to be 7 days a week, 2 hours a day

“What I really want to focus on is the habit of doing something active daily.”‒ Peter Attia

- That doesn’t mean training every day

- It means at least walking or doing something active

Begin with an evaluation of their fitness level, their level of conditioning

- At the most extreme level, if a person has never done anything and is completely deconditioned: it’s going to be about walking, and that’s about it

- It could be as little as 5,000 steps per day every day on relatively flat ground

- And there are so many ways to progress this

- If a person is a little bit more conditioned, Peter likes to put weight on them out of the gate

- He’d like to have the do some rucking, maybe 20 lbs

- Get them moving under a little bit of load

There are lots of other things to consider

- If a person is open to starting with bodyweight exercises, that’s a very helpful way to begin doing things

- Isometric things are safer for individuals who haven’t done much conditioning in the past

- As opposed to isotonic movement-based exercises, meaning strength movements where the muscle is changing length

- Isometric things are safer for individuals who haven’t done much conditioning in the past

Peter has strong thoughts on how to begin cardio training

- We’ve spent a lot of time talking about the importance of VO2 max

Working with a patient who hasn’t done training, we do not do VO2 max workouts ‒ Peter does not believe in starting people with interval training without building an aerobic base

Aerobic base (zone 2)

- Start building in a manner that’s consistent with where they’re coming from

- It might be just walking ‒ incline walking

- Riding a bike

- If the person doesn’t have the lower back flexibility and strength, it could be on a recumbent bike

- Peter explains, “If you forget everything else, remember the following, you want to make sure that in 3 months they feel better, they notice that they are fitter, and their appetite to exercise has grown.”

- That’s the most important thing if you’re viewing this both as a participant or as a trainer

Improving aerobic capacity: the malleability of the system, the importance of consistency, and setting long-term fitness goals [25:15]

What do we know about the ability to improve aerobic capacity? Is that something that can be improved in someone who is older and untrained?

- To Peter, the most amazing part of this is how malleable that system is

- You could make the case that the physical system (aerobic capacity strength) is even more malleable than our cognitive systems

- And we know that our cognitive systems are quite malleable

- You could make the case that the physical system (aerobic capacity strength) is even more malleable than our cognitive systems

One study that really jumped out to our team was looking at percent improvement in healthy older people and healthy younger people

- There was a study that did a 6-week aerobic exercise, they used a cycling training program to assess changes in VO2 max, oxygen consumption, workload, and endurance

- In the older group, these people averaged 80 years of age

- In the younger group, the people averaged 24 years of age

- These groups couldn’t be further apart

- In both groups, there was about a 13% improvement in VO2 max

- A 34% improvement in maximal workload (That’s basically how many watts could you hit)

- A 2.4-fold improvement in endurance capacity

- Peter found this staggering and would not have predicted this prior to seeing this study

- Understand that the absolute levels of all of these things were significantly higher in the 24-year olds (that’s a given)

What we’re talking about here is the malleability of the system. What we’re talking about here is how much could individuals improve in six weeks? And the answer is they both improved dramatically.

Peter points out something else, about deconditioning

- This particular study followed the 6-week training cycle (that he just described) with an 8-week deconditioning period

- The older group declined much faster than the younger group

Both groups were able to see significant gains, but the older you were, the quicker you lost those gains with inactivity ‒ this speaks to consistency

You can’t overstate this analogy of compounding

- If anybody really wants to understand how compounding works, just pull open Excel and build a very simple formula that shows what happens if something compounds at 2% per month or 1% per month

- It becomes so nonlinear our brains can’t comprehend that

- Of course Peter is not suggesting that the gains in exercise will compound at that intensity, but the idea is how much fitter you can be after years of doing something

A lot of the literature in VO2 max training suggests that people are capable of improving their VO2 max by 13%

- Like the study just discussed

- People will hear that and look at the table (shown earlier) and say, “There’s no way I’m going to get to the top 2% of someone two decades younger. That would require literally increasing my VO2 max by 80%.”

- Realize that the study just discussed was only 6-weeks long

When we give our patients these audacious goals, we talk about these as 2- and 3-year goals. So it’s very important to understand that whatever we’re talking about here, we’re talking about over a very long period of time.

- With the long game on VO2 max, the elite category also drops

- In the table shown earlier, the elite category of a 40-year-old is not the same for a 70-year old

- So if you are making that progress and you are increasing just as you age, the categories are also going to decrease, and you’re naturally going to movie up as long as you’re maintaining

- Peter has all of these crazy goals, and one of them is, “What’s the oldest I can be such that my VO2 max in milliliters per kilogram per minute exceeds my age?”

- At some point that will cease to be true: there’s no 80-year-old whose VO2 max is 80

- The question is where does it happen?

- Does it happen when you’re 40? Probably for most people

- Can you push that to 50? 60?

The only way to start to play that game is to basically get in shape and stay in shape

Starting cardio training: base building, starting with low volume, and zone 2 training [30:45]

- Once we’ve established that a person has the basics and they’re not immediately injured, they have the ability to start doing some cardio training

Start with base building

- Even for someone like Peter, who trains a lot, 80% of his training volume is at zone 2

- Only 20% of his training volume is in the VO2 max range

“Understand that I am not training for anything other than the sport of life.”‒ Peter Attia

- If Peter were still training to be a cyclist, he would do something very different than what he is saying

- What he’s stating is far less intensive than someone who’s trying to be a master’s-level athlete in _____ (pick your endurance sport)

For the person who is new to this, Peter would be really happy if he could them them to start 2 days a week, 30 minutes per session

- They’re not going to improve enough

- They’re going to experience no improvement

- If Peter reduced his training volume to that level, he would probably go backwards

- But remember, we’re starting with a person who’s very deconditioned, and they will actually see a training benefit at such a low volume

- Peter is not going to throw them in a 3-4 hour a week training; we’re going to start them much lower

How to determine where your zone 2 is

- When we talk about zone 2, we’re not talking about the same zone 2 that shows up on your Polar heart rate or your Apple Watch or whatever other device you’re talking about

- We’re talking about a very specific mitochondrial level of zone 2, and it’s referring to the highest level of work that you can do while keeping lactate at effectively an indefinite steady state

- Which for most people tends to be below 2 mmol

- Once you’re exercising and lactate gets above 2, you’re probably not going to be able to sustain that for a couple of hours (which is effectively what we’re talking about here)

- Because metabolically you are going to move to an area where you’re generating too much hydrogen along with too much lactate and the muscles are going to be compromised

- If you really want the gold standard for measuring zone 2, you’ve got to be checking lactate levels

- Peter doesn’t really advocate that for people, especially if they’re starting out

- Peter checks it, but he’s probably an outlier here because he enjoys that level of precision

There are 2 ways for beginners to determine zone 2

- 1 – The rate of perceived exertion (RPE)

- 2 – The talk test

- [Peter explains this further on the website]

- You can also use Phil Maffetone’s MAP formula [it’s MAF: maximum aerobic function]

- 180 minus your age is a target heart rate

- And then if you’re really new to the thing, you might even subtract 10 from that

- So a 60-year-old is going to potentially be as low as 110 beats per minute at a target, and as they get fitter, that’s probably going to go a little bit higher

- Peter points out, “You don’t want to be too wed to this as you get more and more involved in your training because the fitter you get, I think the more variability you’ll experience based on recovery.”

- For example, Peter’s Maffetone formula would have his heart rate be 129

- But 129 is never in zone 2 for him, except on the worst day

- His zone 2 is almost always going to be in the high 130s and sometimes in the low 140s

- Realize that as you get more conditioned, the formula may be less and less valuable, and you will rely more and more on RPE

- Or if you really want to take it to the next level, you might even start using lactate

When not to test lactate levels

- If a person is deconditioned, we will not use lactate on them because an individual that’s coming in who’s metabolically unhealthy tends to have very high resting lactate

- There were people walking around with a lactate of 2 mmol at rest

- Clearly in that person, using lactate provides no value and you should rely on heart rate and RPE

After a person has been doing 2 days a week, 30 minutes a day, how long do you like to see that consistency before you slowly increase either the duration or the number of days?

- In part, it comes down to how they feel

- Peter wants to inspire within them an appetite to do a little bit more

- This sounds silly, but when you’re starting out some of this stuff, a lot of it is just the growing pains of being able to sit on a bike and your butt doesn’t hurt

- Or being able to walk on a treadmill and making sure that their knees aren’t aching, or things like that

He would say within 8-12 weeks, he would want to start pushing frequency and/or duration

- There’s not a right answer here

Peter likes to push frequency before he pushes duration

- Go from 2 to 3 to 4 sessions at 30 minutes before you start going to 45-minute sessions

Eventually, he wants the sessions to be at least 45 minutes each

The critical role of Vo2 max in longevity [36:45]

The other side of cardiorespiratory fitness is VO2 max

A few graphs that are helpful in looking at why VO2 max is so important as people age

Figure 3. Relative mortality risk associated with specific clinical characteristics. Image credit: JAMA 2018

- This was a graph Peter was able to get into the book

- He fought hard for this one because nobody wanted it in a book (and he can understand why)

- This is a figure that shows the hazard ratio of various comorbidities and performance subgroup

A hazard ratio gives you an estimate of relative risk

- Let’s start with the comorbidities because that’s easier to understand

- If a person is a smoker, are they at increased risk of all-cause mortality (death from all causes)? Yes

- The question is how much

- If you compare a smoker to a non-smoker and ask the question, what is the probability of that smoker dying in the coming 12 months from any and all causes?

- The answer is, it’s 41% greater than the non-smoker

- What if you take two people, one with coronary artery disease (known CAD) and the other without?

- That’s about a 29% greater risk for all-cause mortality

- What about somebody with type 2 diabetes?

- It’s a 40% greater risk of all-cause mortality in the coming year

- What about high blood pressure (hypertension)?

- 21%

- What about End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD, somebody who’s on dialysis awaiting kidney transplant)?

- A whopping 178% increase in all-cause mortality

Now what we do is we do the same mortality analysis on that massive cohort of people for whom we have VO2 max data

- These are the data that we showed earlier where we looked at people in those quartiles

- What Peter does every time he runs a patient through their first VO2 max test is he figures out where they are

For the person in the 25th to 50th percentile for their age

- Peter explains, “Look... if I were just to compare you from your level at the 25th to 50th percentile to someone who’s in the 50th to 75th percentile, the hazard ratio is 1.41. In other words, you are 41% more likely to die in the coming year than somebody who is that much fitter than you.”

- [see the row in the table above labeled, “Below Average vs Above Average”]

- This puts some numbers to what can be gained by going from a below average VO2 max to an above average VO2 max

It’s not lost on anybody, but that’s the exact same hazard ratio of a smoker to a non-smoker ‒ that’s how big the difference is if you go from below average to high VO2 max

- So now you’re going from the 2nd quartile to the 3rd quartile, it’s a 100% difference in risk [a HR of 2.0]

- It’s a doubling of the risk of death for that coming decade

- Even going from high to elite, there’s a 29% difference in relative risk [the HR is 1.29]

- Peter won’t go through the rest of these numbers here, but they’re all staggering

“When I talk about how VO2 max is the single most important biomarker we have for lifespan, these are the data from which I make that claim.”‒ Peter Attia

More about the value of VO2 max as a biomarker for lifespan

- There are other data that are identical to this on different cohorts, but the point is there aren’t other biomarkers that will give you hazard ratios of this magnitude

- People often ask, “Why is that the case?”

- Peter thinks the answer is that VO2 max is probably a remarkable integrator of work

- It is not a biomarker that changes quickly and easily to the magnitudes required to do this

- You’re not going to take your VO2 max from low to elite in a year

- Peter would argue you absolutely can do it, but it’s not going to happen in a year

- Therefore when it happens, it’s going to reflect an astronomical volume of work that has been done and the benefits of that work are what are being captured in the VO2 max number

A graph that illustrates the value of VO2 max for healthspan

Figure 4. How VO2 max declines with age and its relation to every-day tasks. Image credit: Jayson Gifford

- This is another figure that Peter shows patients all the time

- We’re probably building another one because there’s a couple issues he has with this figure

- Namely, it stops at the age of 75

- Peter wants to see this data extended to another 2 decades

- He realizes that it’s harder and harder to get those data, but he thinks we can estimate them

What this figure shows is really the other bookend of why we want a high VO2 max

- The figure above and the discussion we had a moment ago makes it abundantly clear that if you want to live a long life, you better have a high VO2 max

- This figure says if you want to live a good life, you better have a high VO2 max

This gives you a very clear all-in-one view of what actually happens as your VO2 max declines: you lose capacity

- The graph has a lot of information on here, but it can basically be distilled down into the following

You have 3 curves for the purpose of illustration

- 1 – People in the top 5% (shown in green)

- 2 – People right at the middle of the pack (shown in black)

- 3 – People in the bottom 5% (shown in red)

- For anybody paying attention, these data are pulled from a different data source than the previous data

- Peter doesn’t think this is as rigorous a data set, and therefore the numbers don’t line up completely

- So the 50th percentile here is not the 50th percentile elsewhere

- But for the purpose of illustration, it’s not important

- The x-axis is time; so as age marches along, you are watching a reduction in VO2 max (which is the y-axis for all curves

Observations

- 1 – It doesn’t matter how fit you are, your VO2 max is going down, down, down

- The problem with this graph stopping at age 75 is that it deprives a patient from seeing that the curve doesn’t continue along the trajectory of what came before it

- It actually gets steeper

- 2 – What you realize pretty quickly is that depending on where you want to be (and that’s demonstrated by the activities on the right), you’re going to need to be pretty high to avoid the fall

- 3 – It’s showing you that if you want to be able to run 10 miles an hour on flat ground, you need a VO2 max in the mid to high 50

- 4 – If you want to be able to run 6 miles an hour (which is a 10-minute mile), up a very steep hill, you need to have a VO2 max of 50

- 5 – As you walk down this list, you see that the VO2 max requirement goes down as the aspiration goes down

The point that isn’t really clear on this curve is at what point does the VO2 max become rate limiting for activities of daily living? And that’s in the high teens approximately

- Having studied these types of data for a very long time, Peter knows that for himself personally, he has to be way above the top of the green curve at the outset if we wants to be completely unencumbered in the last decade of life

- You need to have a very high level of fitness when you’re in midlife

- By the way, this tends to be true for most of his patients when we put them through the Centenarian Decathlon exercise

- Most people, at least based on what they’re telling you they want to be able to do in the last decade of their life, are going to require a VO2 max of about 30 (so high 20s to 30) in the final decade of their life

“You need to have a very high level of fitness when you’re in midlife. And if you don’t, that’s okay. You have time to do it, but don’t wait too long.”‒ Peter Attia

How to introduce VO2 max training to older or deconditioned individuals [46:15]

When do you start training for VO2 max?

- Start in zone 2 a few days a week

- Obviously, 2 days a week of zone 2 (30 minutes a session) is a lot different than a VO2 max exercise

Peter wants to build a reasonable aerobic base before he starts punching VO2 max

- He explains, “The wider the base, the higher the peak.”

- [Peter is referring to the Fitness triangle, explained most recently in the Quarterly Podcast Summary 1

Figure 5. The size of the fitness triangle relates zone 2 to zone 5 training.

- You do experience increases in VO2 max just from base-building aerobic activity

- So if you take a person who’s completely deconditioned, and you put them into just a zone 2 program, and you slowly add duration and frequency to that, and then you retest their VO2 max, it’ll be higher even if they have never done a single interval

But ultimately to really start to boost VO2 max, you are going to need to add more intense movement

The easiest way to do that is just to add a little bit of interval training to the zone 2 workout

- This is the way we typically do it with our patients, in a really detrained individual or untrained individual

- For example, if a person is doing their zone 2 on a treadmill, and let’s say you’ve got them walking 3 miles an hour

- After a few months, they can handle 3 miles an hour at 4% or 5% incline

- Finish the workout doing 5, 1-minute “bursts” where you increase the slope from 5% to 10%

- And you’re just going to do it for a minute

- You do a minute on and take a minute off; a minute on, take a minute off

- It’s going to really tire them out

- You start to get them used to increasing the intensity

- This also becomes a chance to assess if this is going to be something that they can do safely or are they going to completely deteriorate in form?

Peter used to do some really stupid things for VO2 max training

- He’s lucky he never got injured

- He used to do deadlift Tabatas [don’t try this]

- He would put 225 lbs on a bar and see how many reps he could do in 20 seconds, then take 10 seconds off

- Repeat that 8X

- He did a lot

- He would put 225 lbs on a bar and see how many reps he could do in 20 seconds, then take 10 seconds off

- But when he thinks about the risk he was putting himself under from a movement perspective

- Being under that much fatigue in the 7th and 8th round of that where you’re trying to push harder and harder

- It just doesn’t makes any sense in someone like him who has a lot of training background

Peter wants to make sure people are doing these intervals (which we’ll talk about in a second) in an activity where the form isn’t going to deteriorate to the point of injury

The gold standard for how to train VO2 max

- This is something we have discussed at length [see the “Selected Links” section]

The sweet spot for that energy system is 3-8 minutes of work, and is you do as much work as you can at a steady state in that period of time

- At the low end of that is 3 minutes, meaning how hard can you push for 3 minutes such that it’s roughly the same level of work output?

- For example, you can track watt, if you’re on a bike

- But by the end of three minutes you’re truly spent

- At the upper end of that, it would be 8 minutes long

- Obviously it’s going to be far less wattage but the same physiologic response

- Which is by the end of it you are truly gassed

- Obviously it’s going to be far less wattage but the same physiologic response

- Personally, Peter tends to gravitate to 4-5 minutes

- But it’s great to mix it up

Gauging how hard to work

- When Peter’s doing a 4-minute interval, he barely notices the first minute

- So if at the end of the first minute of a 4-minute interval, you’re dying, you went out way too hard

- It’s okay, try it the next time

- So if at the end of the first minute of a 4-minute interval, you’re dying, you went out way too hard

- At 2 minutes, he’s still feeling pretty darn good

- And believe it or not, sometimes he’s wondering if he shouldn’t be pushing a little bit harder

- At 3 minutes, he’s truly wearing it

- That last minute is brutal

- And that’s again assuming he’s largely holding power constant for the 4 minutes

- So that’s a general rule

- The way Peter describes it is 3/4th of the way into the interval, you should be at the 50% level of your pain

- At 3 minutes if it’s a 4-minute interval

- At 6 minute if it’s an 8-minute interval

Once a person is ready to graduate into a dedicated VO2 max session, Peter wants to see them doing that once a week

- If you’re training to be an elite level cyclist, you’re going to have to do it more than that

- But if you’re training to just minimize risk and maximize gain, Peter wants to see people start to push those

- Maybe the first time they do it, they can only do 4 rounds of that, but eventually you’ll get up to 5, 6, 7, 8 rounds

- If we’re talking about 4-minute intervals, and when you put in a warm-up and a cool-down, then we’re talking about a 60 to 75 minute workout here

- You’re doing that at a 1-to-1 work-to-recovery ratio (4 minutes of work and 4 minutes of very, very passive recovery, not a hardcore active recovery).

Even though VO2 max is so important, if you’re in an older population who maybe is deconditioned, it’s important to get an aerobic base before starting VO2 max training, and when you do start, it’s important to take it slow and build that over time so you can enjoy it and not get hurt

“The older and less conditioned you are, the less I want you to hurt during those VO2 max intervals.”‒ Peter Attia

- Peter can speak from experience, the level of pain he is in today when he does his VO2 max sets is nothing compared to what it was 10 years ago

- 10 years ago, he was truly pushing to the point of vomiting

- He does not push that hard anymore

- And in 10 years, when he’s in his early 60s, it will be even less of a push than it is today

The name of the game is play the game and stay in the game forever. And so we are really looking to minimize injury here and we’re looking to minimize burnout.

- The first few times a person experiments and dabbles with these 4-minute intervals, Peter actually wants them to come away thinking, “That wasn’t too bad.”

- Great; try a little bit harder the next time, but we’re not here to wipe you out after the first session or even the first couple of rounds

Options for performing zone 2 and VO2 max training [53:45]

Zone 2 training

- For zone 2, believe it or not, you’re kind of limited because of the steady state nature of it

- For Peter, zone 2 is always on his stationary bike, so on a trainer (if he’s not traveling)

- If he’s traveling, he will usually do it on an inclined treadmill ‒ he goes to what he considers a normal brisk walking speed (which is 3.4 to 3.5 miles per hour) and then he just takes the incline up

- He might warm up at 10 degrees (or 10% grade)

- He usually winds up at about 15% grade

- So 3.5 mph at 15% grade, that’s his zone 2

- If he’s traveling, he will usually do it on an inclined treadmill ‒ he goes to what he considers a normal brisk walking speed (which is 3.4 to 3.5 miles per hour) and then he just takes the incline up

- You can do zone 2 on a rowing machine if you’re a really good rower

- But for most people, they’re not efficient enough on a rowing machine, so that you typically end up blowing up and through their zone 2 ceiling

- Peter can do it on a StairMaster, but he has to be careful about it

- Peter points out, “When you’re using StairMasters and treadmills and all these things, remember, you probably don’t want to have your hands on the device because there’s too much variability in how much of the stress you’re taking away.”

- If you’re in a treadmill and you’re holding onto it, there’s so much variability in how much of the load you’re alleviating that Peter prefers to just go hands off the machine and settle in at a steady state that’s going to be consistent

VO2 max training

- The good news is for VO2 max is you have many more options

- This is where Peter rides his bike outside

- You could be doing almost anything provided that there’s enough space for you to do it for at least 3 minutes

- Swimming is a great way to do VO2 max training because you don’t have the impact

- You could do it on a treadmill if you wanted to and you could run or you could again just walk at a steeper incline if your zones permit it

If someone is older (65+) and they haven’t done zone 2 before, is it better to start on a treadmill or a bike?

- All things equal, if this is the only exercise a person is going to be doing, Peter might lean a little bit towards the treadmill if they were truly agnostic

- Just because at the end of the day, walking is a more valuable skill than cycling

- Cycling has no application beyond cycling

- Whereas walking is a very important part of who we are

- Just because at the end of the day, walking is a more valuable skill than cycling

- It’s our superpower to be bipedal; so the more time you can spend doing it, the better you are

- For someone like Peter, it’s kind of moot because he walks a lot anyway

- He’s forcing that system to work elsewhere; so he might as well do something he enjoys the most

- Which is probably riding a bike

The ability to make gains in strength and muscle mass as we age [57:00]

What do we know about the possibility to gain muscle mass as we age?

- This is not dissimilar from what we talked about on the cardio front

Research is very consistent here in demonstrating that resistance training can increase muscle strength and muscle hypertrophy at any age

- You tend to get into very small studies here, but when you look at large pooled analyses, you can see that even if you limit your analysis to people over the age of 80, training can offset losses and in a deconditioned individual, can actually make gains

- These are people who are clearly in that area of being on the downhill for strength and hypertrophy

Just as Peter made a case for why you can’t overstate the importance of cardio training (both at low and high intensity), he doesn’t think you can overstate the importance of strength training

“I just don’t think there’s anybody out there who shouldn’t be lifting weights. I can’t think of a case.”‒ Peter Attia

- You have to be lifting weights, regardless of age, regardless of sex, regardless of injury

- You have to work around all of those things

There’s a similar study to the one Peter cited earlier that is so illustrative of this point

- This study looked at people in their late 70s and early 80s and people in their 20s

- At the outset, they measured 3-rep max for leg extension

- They put them on a 6-week resistance training program

The people in their late 70s and early 80s had a 78% increase in their strength, which is almost identical to the 83-84% increase that was found in the younger individuals

- It’s important to understand that yes, these people were significantly different in the absolute strength that they had

- The average leg extension in the people who were in their late 70s and early 80s was only 22 kilograms versus 178 kilograms for the young participants

- Nevertheless, everybody has the capacity to improve and therefore everybody needs to be doing this (a very important point)

The importance of type II fibers

- We’ve talked about this in previous podcasts, most notably with Andy Galpin on a couple of occasions [episodes #239 & #250]

- One thing that Andy discussed that really stuck with Peter was the atrophy of type II fibers ‒ he almost described it as a hallmark of aging

- Type II fibers are the glycolytic fibers, they are more powerful, they have more contractile force

- They are the ones responsible for power

- They are not responsible for endurance

- Type II muscle fibers peak when we’re in our 20s

- Peter shares, “Every day I’m sort of thinking about what am I doing to preserve them and minimize their loss.”

- Another study demonstrates that type II muscle fiber cross-sectional area were increased by 27% in men aged 60 to 73 with 13 weeks of resistance training

You have to train relatively heavy for your level of strength (you have to push to make those results happen), but this can be done very safely

How to implement strength training for older individuals [1:01:00]

For the hypothetical patient who is older, has not been strength training, and DEXA shows low muscle mass, how do you start to incorporate strength and resistance training?

- There’s a parallel here with what we talked about on the endurance side, and Peter always starts from the same vantage point: if you’re new to strength training, he wants to make sure that in 2-3 months you will look back and think, “I enjoyed that. Wasn’t as bad as I thought it was.”

- If someone hasn’t lifted weights before, there’s a reason

- There’s something about it that they are either intimidated by, afraid of

- Or they didn’t think it was valuable enough

- 1 – Peter wants to undo that reason

- 2 – He wants them to feel something is different

- Maybe they could only do this many pushups when they started and now they can do that many

- Or maybe they started at this weight on leg extensions (or leg presses) and now it’s 50% higher

- First principle is increasing weight over time

- Second principle is we are going to start with volume more than we are going to start with load

“Muscular resistance matters more to me than strength at this point.”‒ Peter Attia

- Peter is not going to lead in with, “Let’s go after those type II fibers.”

- It’s going to be, “Let’s work on the type I fibers.”

- [type I and type II muscle fibers are discussed extensively in episode #250 with Andy Galpin]

- He doesn’t care if you need to do 15 to 20 reps on every exercise

- At this point, he’s not even concerned with all the nuances of RPE

- We’ve talked about this on many podcasts, including not just the podcast with Andy, but with Layne Norton [listed in “selected links”]

- The data are that the number of reps you do for hypertrophy and strength (especially for hypertrophy) don’t really matter provided you get to within 1 or 2 reps of failure

- We’re not even really going to push that out of the gate

- We might prescribe, “Pick a weight that you fail at about 12 to 15 reps”

- We’re less concerned as to whether that’s an RPE 2 or an RPE 4

In parallel to this, you’ve got to be working on stability

- Stability stuff is not necessarily weight-based

- This is where you’re working on intra-abdominal pressure exercises, really making sure that they can kind of pressurize the cylinder as we stay, breathing exercises, so a lot of the stuff we borrow from DNS and PRI

- [Discussed in episodes #131 with Beth Lewis and #152 with Michael Rintala]

- We want to make sure that they can move their ribs correctly

- And you want to make sure that they have the ability to even recruit muscles correctly

- A lot of those things are kind of hard

Peter will never forget an example Beth Lewis had him do of the the early times he met her

- She had him lay on the floor, on his back, his knees are up but his feet are flat on the ground (in a very relaxed position)

- It was an exercise around being able to sequentially recruit hamstrings one leg at a time and put the foot down into the ground and pull it back

- That’s a pure hamstring isolation exercise, and despite having very strong hamstrings, Peter really struggled to do that exercise while keeping his pelvic floor stable

Those are the types of things where you’re not going to get injured, but you’re going to have to learn to start recruiting and controlling a muscle; and, once you do that, you’re much safer lifting

How do you think about resistance training for people who are in the even older category (65+)?

- You just have to do everything a lot slower

- You’ll do TRX, but you want to be much more stable in the positions you’re doing

- Start by only using machines

- Peter wouldn’t want them using dumbbells (outside of maybe doing carries)

- No picking up dumbbells to do lunges or thing like that (save that for phase II)

DNS (dynamic neuromuscular stabilization) positions are very important for people of any age

- Teaching an older person, especially a person who’s new to physical activity, some of those positions is very valuable because

- 1 – It’s doing all the stuff Peter talked about a second ago

- 2 – The person is also getting comfortable with being on the floor and moving on the floor

- Peter explains, “This is something that you and I will take for granted, Nick, for some time, but people 20 years older, 30 years older than us, can’t take it for granted that being on the floor, moving on the floor and getting up on the floor unassisted is something that they should be able to do easily.”

For someone who is 50+ and they walk into their local gym, would you encourage them to start on machines at first, at lower weights, and slowly work up the weight before grabbing free weights/ dumbbells?

- Everybody is going to be different

- If this person happens to have a trainer who’s really good then they may be able to push things a little bit quicker

If this person is going to be doing a lot of this stuff alone in a gym, then yes, stick with the machines

- Peter wouldn’t advise trying to do dumbbell presses or kettlebell exercises or anything like that

You really want to build your strength and stability with body weight and with machines before you progress

Advice for avoiding injury when strength training [1:07:30]

A lot of older people may be concerned about resistance training due to potential injury. How do you speak to them about how they should think about this?

- You always have to think about this because you’re always balancing providing enough training stimulus to get the benefit

- Remember, training is a hormetic activity

- It has to create a stimulus, whether that be on the aerobic system, whether that be for the type I fiber, the type II fiber

- There has to be a stimulus that comes from pushing outside of a comfort zone

We have to have that training stimulus, but we know that if we do too much, we’re going to get injured

- By now Peter has made the case for why injury must be avoided at all costs because injury means time to decondition

- And the older we get, the more problematic that gets

Peter thinks back to the injury he sustained when he was 27-years-old

- It left him unable to walk for 3 months, and unable to do much of anything for 9 months

- If you look at him today, there’s really no lasting effect of that

- But imagine if that had happened when he was 70

- That’s it; his life is over

- He would never get back to where he was

It’s probably safe to say that the most common reason for injury when you’re starting out is progressing along the intensity axis too soon

- We talked about how you push frequency, you can push duration, you could push intensity.

Peter’s advice: move the frequency, then the duration, lastly the intensity

- That’s clearly true on the cardio training side, but it’s also true on the strength training side

Lack of neuromuscular control is another important part of injury

- That accounts for many things from why people fall more frequently as they age to how people get injured

If we limit it to: why are individuals getting hurt when they’re lifting weights?

- A lot of it is maybe they’re moving a weight that they can’t control

- We’ve talked a lot about the importance of being able to control the eccentric phase of a movement

- We’ve all seen someone in the gym who’s just throwing weights around and getting away with it, but you’re going to stop getting away with that the older you get

We want to really make sure that people have the coordination, they’re doing the types of drills, like agility ladders, hand-eye coordination exercises, ball tosses, such that they’re generating neuromuscular control in addition to strength

The other big area where we see injuries is due to a lack of movement variability

- Do you need to squat and deadlift and bench press? No

- You can accomplish many of those goals using single-leg variants that are far less weight

- Even something like a bench press with a bar, Peter would much rather substitute in (once you’re ready for that) floor presses and single arm floor presses

- You’ll be laying on the floor with knees up, feet flat on the ground, one arm straight up the other arm doing the presses

- What’s nice about that is on a floor press, your range of motion is nowhere near what it is on a bench because you’re obviously not going to be able to bring the elbow below your back, which you could on a bench

- So you lose a bit of range

- It’s clearly not “as good a pec exercise,” but there’s also a very good margin of safety there

Think about how much harder it is to hurt yourself doing a floor press than a regular traditional bench press

- These are just some slight examples of ways that you can think about minimizing injury

When Peter was coming back from shoulder surgery

- He spent probably a year of just doing floor presses before he proceeded to go back onto a bench

Risk of falls: the devastating consequences and the factors that increase fall risk [1:12:15]

- Fall risk is important not only for people in this age category, but anyone listening who’s younger

- It’s motivation to train at a younger age

- It’s like saving for retirement at a much earlier age

- Peter thinks back to all the failures of traditional medical training

- In 4 years and $250,000 of education at Stanford, how many hours of lecture did he have on exercise? Zero

- When was this discussion about falling presented to us as medical students? Never

In the United States, over 14 million (or 25% of people over the age of 65) will fall each year

- Now, to be clear, that’s people who report it

- We believe that that number is significantly higher

This risk goes up quite non-linearly

- By the time we’re talking about octogenarians and nonagenarians, the annual incidence of falling is at least 50%

Recall that the risk of death from that fall, depending on the series you look at, will be somewhere between 15-30% of those falls, if they result in a broken hip will result in fatality within the 12 months that ensue

- The graph below was in a newsletter a couple years ago

Figure 6. Death rates from falls in the US from 2007-2016. Data from: MMWR 2018

- You don’t really need any statistics to understand this; you just need to look at the graph

- This is the normalized death rate per 100,000 people over the last 15 years

- These are data from the CDC

You can see that just from 2007 to 2016, we’ve seen a 30% increase in fall deaths

- To put it in perspective, the projection is that by 2030, we’re going to expect to see 7 fall deaths every hour in the US

- Again, it’s very difficult to wrap our minds around this problem

Figure 7. Falls and injuries in older adults in 2018 and projected data for 2030. Image credit: CDC

- If you look at the data in 2018 [in the figure above], we’re talking about 36 million falls reported to 8 million injuries

- That looks like it’s going to very quickly become 52 million falls with 12 million injuries in about 5 years for people over the age of 65

Peter’s takeaway: it’s safe to say that falls pose not by magnitude, but certainly by severity, as significant a threat to an aging individual as the typical “horseman” that we’ve spoken about so often

What do we know about the reasons for falls? What makes a fall worse than the others?

- There’s 2 ways to think about this

- 1 – What is it that increases our susceptibility to fall? Why is that going up as we age?

- 2 – The severity of the fall also goes up as you age

- In Outlive, Peter included a figure that shows death rate of falls by decade

- [This figure was also discussed in AMA #37: Bone health]

Figure 8. Cause of accidental deaths in the US by age. Image credit: CDC database 2019

- Peter adds, “If you’re trying to explain to somebody what exponential growth looks like, you just show them that graph.”

- 2 things are compounding non-linearly and you put them on top of each other

Let’s talk about why this is happening

Why are there more falls?

- It’s going to be lower limb weakness and we should double-click on specifically the role of the toe there

- We had a recent podcast with Courtney Conley that discussed that

- Difficulty with walking and balance: remember vestibular changes kick in around the age of 65, so all of us become less visually capable and we have less just innate vestibular capacity, visual difficulties, foot pain, poorly fitting footwear as we age

- Then, of course there’s medications that people take

- The older we get, the greater we see the incidence of hypertension, which does need to be treated

- Hypertension is an enormous risk for stroke and heart attack, but sometimes we over treat it and people become orthostatic and when they stand up, they get lightheaded and fall

- That can be devastating

- Things that are not necessarily age related: just having uneven steps around, clutter, all of those things play a role

The more of these factors you check off, the more likely you are to fall

Why are falls more catastrophic as age goes up?

- An amazing statistic is that the leading cause of traumatic brain injury in people over the age of 65 is falling

- 95% of hip fractures are driven by falls

Clearly, frailty is the leading cause of this

- Frailty means poor muscle mass, poor reactivity, and low bone density

- Those are probably the things that are driving the severity of the fall, which are so much higher in a person who’s older than a person who’s younger

- Back in the podcast with Andy Galpin, where we talked about the atrophy of the type II muscle fibers, Andy used that as the great example of another reason why falls go up as people age

- If you or I step off a curb we weren’t expecting to be there or when you’re stepping from one level to another and the level is different than you expected, that immediately destabilizes you

- The ability to react to that very quickly and get a firm footing, that is a very power-driven movement

- That’s not really about how strong you are

- It’s actually about how explosive and powerful you are

- That is a type II muscle fiber phenomenon

- And as you watch the atrophy of those type II fibers, you have far less reactive speed in your feet, and therefore, you’re more likely to fall in response to that

Again, the more we can train these systems, the better we are going to be able to resist falling

Mitigating fall risk: the importance of foot and lower leg strength, ankle mobility, and balance [1:19:45]

Courtney Conley talked about the role the foot plays in fall risks, in particular toe strength

- That is a great episode, absolutely worth going back to if you haven’t listened to it

- Courtney and Peter put together videos

- Courtney explained that toe strength was the biggest predictors of falling in people over 65

- In that podcast, Courtney ran Peter through a bunch of tests to determine toe strength

- 1 – One of those tests was a little card that you put under your toes (it’s a dynamometer), it measures the force that you can push each toe down as the card is trying to be pulled out

- The rule of thumb was your great toe should be able to push down with at least 10% of your body weight, and if it can’t, it’s too weak

- Toes 2-5 collectively should be able to push down about 7% of your body weight

- 2 – Another great test was the lean forward test ‒ this was when you’re standing up straight, you have this little laser device and you shoot it against a wall and you get a distance, and then you lean forward and without catching yourself

- Just letting your toes basically do the work to see how far they support you

- You should be able to move at 4.5-5 inches

- 1 – One of those tests was a little card that you put under your toes (it’s a dynamometer), it measures the force that you can push each toe down as the card is trying to be pulled out

- This episode added so much more to how Peter thinks about the importance of this stuff

- He’s always thought of the foot as important

- But in the past 5 years, the importance of toe strength and feet has been relevant to him for other reasons

- He never appreciated the role it plays in falling

Exercises to build toe strength

- Big toe banded exercises: 40 reps in each direction, if you can’t do the little toe, just focus on the big toe and then the 4 toes

- Training for the Anterior Fall Envelope: 20 reps. 3-5 second holds

Calf strength

- Courtney goes through the benchmark tests for both gastroc and soleus test

- Peter explains, “Virtually nobody I’ve ever seen has been able to pass these tests out of the gate. These are very difficult tests and that tells us that most of us are heading into older age with underdeveloped strength in our lower leg.”

Peter’s takeaway: It’s actually changed my training and I have added much more soleus and gastroc training. And frankly, it’s been at a much heavier weight than I’ve trained in the past because of my understanding of how those fibers work.

Additional exercises for calf strength:

- Any type of calf raise: double leg standing, double leg seated

- To specifically target the soleus, seated is better since the knee needs to be bent >60 degrees

- Do a single-leg calf raise using something as simple as a container of laundry detergent on your knee at home (a full detergent container weighs about 17 lbs)

- The aim is to feel fatigued after about 3 sets of 6-8 reps

- For a challenge, you can slow down the tempo and really squeeze at the top

Ankle mobility

- Courtney put Peter through another set of tests around dorsiflexion and tibial rotation

- He was surprised that he did not pass these with flying colors

- He thinks he passed on 1 side but not the other

- He always remembers something someone told him many years ago, which was if you can’t walk down a flight of normal height stairs, so call it a 7 or 8 inch step (whatever normal is) and keep your toes perfectly pointed forward, you don’t have enough dorsiflexion

- If you think about it, a lot of people when they’re walking downstairs have to turn their toes somewhat out to accommodate the tibial or the shin angle with the foot

- Peter would encourage everybody the next time they’re walking downstairs to actually see if they can walk with feet perfectly parallel and pointing forward

- And if that’s difficult on your lower shin and upper foot, you probably don’t have enough dorsiflexion

Additional exercises for ankle mobility:

- Active dorsiflexion ROM coupled with tibial rotation

- Slant board, this exercise uses the ToePro slant board

Exercises for general balance:

- Lift Spread Reach, this works on activating the extensions of the toes and works on toe splay

- Do 20 reps then try to balance; ideally start with 10 seconds on each side, working up to 30 seconds

- It takes lots of practice

- McHugh Protocol

- Balance on an Airex pad for 3-5 minutes a day for each foot

- This work foot strength and hip strength

Improving bone mineral density through resistance training [1:24:30]

- We talked about bone mineral density in AMA #37

What do we know about resistance training for bone mineral density in older adults?

- This is something that as people get older, they’re much more worried about and looking at

- BMD (or bone mineral density) is one of the 4 pieces of data you get from a DEXA scan

- It’s typically reported as both a Z-score and a T-score

- Now, it’s really important if you are getting a DEXA scan because you want this information, you need to make sure that it’s reported segmentally

- A lot of places that do a DEXA scan don’t give you the hip and lumbar spine readings

- They’ll just give you total body T-score and Z-score, and unfortunately that is not sufficient to understand your risk

- So, you need a T-score for the lumbar spine and you need a T-score for at least one, if not both of the hips

- Some places will just do one, because the concordance between hips is pretty high

Peter explains what a T-score is

- A T-score is the difference between your bone mineral density and the mean level for a 30-year-old of your sex divided by the standard deviation

- If the T-score is below -1, that is defined as osteopenia

- If the T-score is below -2.5, that is defined as osteoporosis

How bones work from a density standpoint

- A lot of this is covered in AMA #37, Peter is just giving the TLDR here

- We basically are in a net bone building phase until our early 20s

- We sort of hit bone peak, and then it’s mostly a decline from that point on

- For women, the decline becomes quite precipitous once they hit menopause, if they are not placed on estrogen therapy

- It has to do with the fact that estrogen is potentially the single most important hormone when it comes to regulating bone health, and the reason for it is that bones respond to load

- This gets to the question, “Why does strength training matter so much?”

- It’s because it is a load

- The bones need a compressive force on them to grow, and the compressive force comes typically when the muscles around them are contracting

- The on thing Peter recalls from that podcast that stood out as even a greater impact on bone strength was wrestling and jiu jitsu

- What happens is when the bone is placed under load, think of it as a strain gauge that measures the deflection of the bone

- And that strain gauge has to communicate through a chemical signal to the osteoblasts and osteoclasts, which are the bone building and bone decaying cells respectively

- The mechanical signal is transduced into a chemical signal, and that’s done via estrogen

- That’s why estrogen is so important because it’s the chemical messenger that says, “Hey, I’m under load. I’m being deformed. Please give me more bone building material here.”

Unfortunately, this is another one of those things that declines precipitously with age and it’s non-linear, meaning the rate of decline goes up by decade

- Loss of bone mineral density is not a constant rate of decline