When Your Profession is On Fire

Length: • 11 mins

Annotated by Mark Isero

When Your Profession is On Fire

On Industrial Burnout Machines

Do you find yourself consistently opening these emails? Do you come back to them or forward them or think about them over the weeks to come? If you value the work here, if you send it to your friends or revisit it, consider subscribing.

You’ll get access to the weekly Things I Read and Loved at the end of the Sunday newsletter, the massive links/recs posts, the ability to comment, and the knowledge that you’re paying for the stuff that adds value to your life.

Plus, there’s the threads: like Tuesday’s The Article, Profile, or Interview That STICKS WITH YOUand Friday’s resource and commiseration-filled Everything You Know (And Need To Know) About Eldercare. A weird combo, but what can I say, Culture Study subscribers contain multitudes.

The comments section of last week’s guest interview about “the trouble with passion” was quintessentially Culture Study. It was the kind of comments section that makes this work feel great — especially because I didn’t even conduct the interview, I only edited it! If you haven’t read the interview yet, it’s snappy and will turn a few screws in your head.

One reader comment turned an additional screw in my head and took me on a mental voyage that I’m probably still only halfway through. That comment came from Lily, who wrote:

I work in climate policy so definitely see some of this at play. For 'purpose' jobs, I think, resisting the pull to work endless hours is as much about keeping ourselves able to sustainably do the work (which both makes the world a better place — we hope — and puts food on the table) as it is about leaving space in life for other sources of fulfillment.

Working in climate policy is a “purpose job,” as Lily notes — a term that is often used interchangeably with “passion work.” Passion work is doing work you feel “called to,” a job that makes you feel very obviously “fulfilled,” a job that announces itself clearly as “making a difference.”

Teaching is passion work, regardless of level. So is a lot of medical work, and non-profit work, and social work. Political organizing, for most people, is passion work; so is religious work (or any vocation to which you feel “called”) and artistic production. Working at a summer camp for pennies is passion work but working as a waitress at a dude ranch (both jobs I have had) — not so much.

In this way, passion work is like obscenity: you know it when you see it. Usually it involves exploitative pay practices (save in the fields with union protections, who are often told that solidarity with their union is evidence of a lack of passion, e.g. “If you actually cared about kids/patients/those in need, you wouldn’t be on strike”).

Passion jobs are often but not always dominated by women, in part because many of them are in “caring” fields where there’s a historic expectation that people (read: women) would and should do this work for free. Alternately, the industry or organization built itself on the free labor of bourgeois married women, so when it did start paying people, there was an understanding that their employees would 1) have a second salary supporting them and/or 2) come from a modicum of wealth, which meant the organization could get away with paying very, very little.

Passion jobs are usually salaried, because there is always far more work to be done than 40 hours a week. Give a passion worker a salary and the additional hours become a testament to their dedication. Passion jobs — at least jobs that aren’t related to the government in some way — also rarely have good or even decent benefits, because naturally your husband has them. (Before you point out that your non-profit is relatively new and didn’t set its benefits with this understanding in mind — they absolutely set them with the industry standard in mind, which is rooted in historical precedent).

Passion jobs often ask workers to pay their own way for conferences and other forms of training, or share rooms if they do foot the bill. Sometimes it’s because the managers at these places are mindless or cheap (Nicole Daniels is particularly skilled at lampooning this type of non-profit boss) but often it’s because line items like development (or benefits, or compensation) have always been conceived of as afterthoughts to the mission, not central to its sustainability.

●

To be fair, some passion-based organizations are trying to move beyond this thinking. If you’re serious about DEI, you have to be — otherwise non-profits are just going to keep hiring the same middle-class educated white ladies. Unions, many of them newly formed, have been a massive part of this reformation movement — and provide models of how you can love your work and also want to be paid fairly for it, with more equity and transparency. (I’m invigorated by the Art Institute of Chicago Workers United — as well as the unions at graduate schools across the country, at podcast studios, in digital media, in political campaigns, in early childhood education, in eldercare, and more).

Some of what these unions are fighting for is pay. And some of what they’re fighting for is the ability for workers to do their job well. That’s what unions have always done! Advocated for working conditions that don’t kill, maim, or injure people (physically and psychologically) for workers to be compensated for that work with a fair and living wage. And that’s what unions are doing now. It’s just the work itself that often looks different.

Even if you don’t have a union, your organization should be asking itself: What does a sustainable workload actually look like? How many hours does it require, and what portion of a person’s whole self should it demand? The ideology of passion work tells us that the answer to that question should be as much as possible, because more work means more benefit (for the kids you’re teaching, for the climate crisis you’re addressing, for the public health problem you’re fixing, whatever). But as much as possible often makes the work itself impossible in the long term.

●

Here, we return to Lily’s comment: “resisting the pull to work endless hours is as much about keeping ourselves able to sustainably do the work [...] as it is about leaving space in life for other sources of fulfillment.”

Guardrails on the work day — on the work week! — make it possible for you to do the work for longer. Not longer hours, but, like, longer in life. It makes passion sustainable. But most passion fields aren’t geared this way. Instead, they implement laissez-faire practices that allow the worker to decide for themselves how much work is appropriate, or enough, or “good” — and allow the workers’ fears (of not being passionate enough) and guilt (of not doing enough) to discipline them.

Within this disciplinary logic, working all the time begins to feel right because it feels like the only way to be right: to be a good and moral person. This thinking holds even if you also feel like you’re constantly falling short, which just leads you to work more — even when your body, your peers, and your family are begging you to work less.

These passion job organizations are burnout factories. Every year, a new crop of eager recruits comes in, grateful to have landed a job doing work “they love” — and every year, a significant percentage of the existing workforce churns out. Some have been there that single year, others for five. They leave not because they’re not good “fits” for the job, but because they can no longer face a life subsumed by it. It’s a massive loss of potential, of institutional and industrial knowledge, and of mentorship opportunities.

As for those who stay and rise through the organization? They’re either so wed to their way of working that they can’t see why others would want another paradigm, think their own trial by fire should be replicated for others.....or they lack significant secondary pulls on their time and energy. They’re often men, and almost always white. (Hence: the notoriously snow-capped passion org).

●

The Passion Job Burnout Machine is different than the burnout machines of, say, Big Law, or investment banking. With those jobs, you know who’s burning you out and why. It’s a very transparent trial by fire: a means to see if you can hack it with a very time-greedy job (that rewards you with very high pay). Passion jobs let you do the dirty work yourself. That’s why it’s so much harder to recover from the damage: it can feel like there’s no one else to blame.

Writing Can’t Even: How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation was my way of processing that blame and shame. I wanted to understand how this sort of thinking became normalized, both societally and personally. Out of Officewas my way of imagining a way of working, in and out of the office, that would allow people to do the work they liked, whatever it was, for longer. Not, like, work til I die because the idea of retirement is a farce longer — more like I don’t want to burn out of my industry at age 37 longer.

You want to get that sweet sweet professional wisdom — the invaluable, textured understanding that comes from doing a job (maybe in different ways, in different places!) for many years, and helping people new to the profession to do the same. But working in a burnout machine takes that sort of gratification off the table.

●

When an industry fails to address the societal and structural factors that make this type of work harder, and relies on workers’ passion to power the whole industry through a snowballing crisis....in those cases, not even a strong union can protect the worker from the burnout built into the system. You go beyond burnout to demoralization, which is the current base temperature of every public educator I know. It’s what happens, according to education philosopher Doris A. Santoro, when “teachers cannot reap the moral rewards that they previously were able to access in their work.”

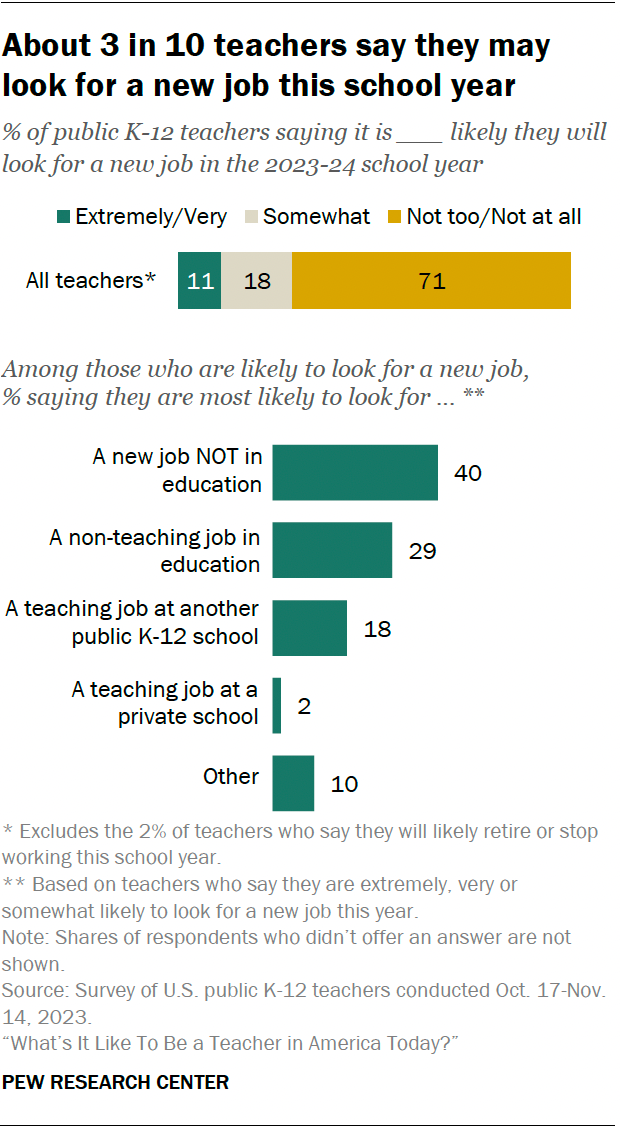

Teacher demoralization was growing before the pandemic, it metastasized during it, and now, according to new survey data from the Pew Research Center, 30% of the K-12 public school teachers are considering leaving the field in the coming year.

The rest of the survey paints a stark picture of the current sentiment of public educators in the U.S. They don’t feel trusted by parents; legislators with little knowledge of what they do are trying to control them; their students are chronically absent, have significant behavioral issues, and are grappling with largely unaddressed mental health issues. If you’ve paid attention to education over the last twenty years, you’re familiar with the contours of this new reality: teachers are expected to be social workers, counselors, politicians, educators....and proficient in strategies to protect themselves and their students from a mass shooter. We don’t train teachers to do that sort of work. We certainly don’t pay them for it.

●

When Pew asked teachers about the biggest roadblock to student and educational success, three answers stood far above the rest. It wasn’t WOKE BOOKS. It wasn’t phones in the classroom. It wasn’t bullying or social media. It’s poverty, and chronic absenteeism, and anxiety and depression.

Those aren’t classroom problems. Those aren’t educational problems. Those are societal problems. When we think about what’s fueling teacher demoralization, we have to start there: we’ve given educators a problem they cannot even begin to solve on their own.

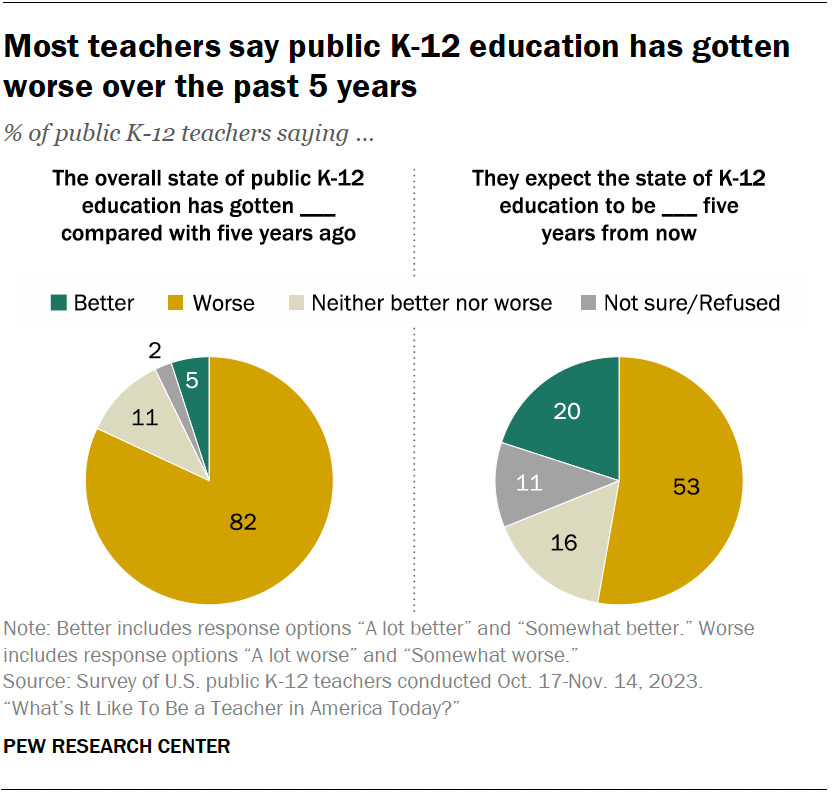

And yet, that’s what we’ve done — while also asking those same teachers to, well, teach. No wonder 82% of K-12 teachers think the educational system has gotten worse over the last five years — and 53% think it will be even worse in five years. Those are the stats of a profession on fire.

The refusal to grapple with these structural issues has led us to the charter school movement, to bourgeois parents taking their kids out of public school even when they philosophically support it, and to ongoing attempts to defund public education. But that understanding of how we’ve arrived at this current moment of educational crisis is too passive for me. The fire is spreading because the fire was set intentionally. In red states, in court cases, in state legislatures, in anti-union messaging, in messaging against local school levees, but also in general pushback against “entitlements” and all manner of policies, passed by both Democrats and Republicans, that exacerbate the wealth gap and exacerbate poverty.

The goal — sometimes explicit, sometimes implicit, sometimes accidental or unintentional — has always been to privatize education. To control the curriculum, of course, but also to wrest control away from the unions and the educators themselves.

Even if the fire wasn’t deliberately set where you live, that doesn’t mean it hasn’t spread there. It’s in its late stages of destruction in Idaho, in other words, but already making significant inroads in the most liberal parts of Washington. And I don’t know if the profession can come back from it, just like I don’t know if higher ed or journalism can come back from the fires consuming them. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t fight back, it just means the amount of already scorched earth is significant.

This is the point where I could take an obvious metaphorical turn: scorched earth produces new life! Fire is regenerative! But these industry-engulfing fires, like the work practices they enforced, were extractive in ways we’ve yet to fully understand. They left a trail of burned out, disillusioned, demoralized workers behind, sure — but they also left a bleak landscape, deeply hostile to innovation, with the vast majority of jobs precarious ones.

So how do we keep doing all this passion work that needs doing? How do educate, and make art, and create spaces to enjoy it? How do we comfort the infirm, and protect the vulnerable, and agitate for a better world? We can agree that the outcome of this type of work is valuable and venerable. It is essential. But the we value the people doing the work, and their capacity to keep doing it — is equally so. ●

Further Reading:

- The Trouble with Passion

- Miya Tokumitsu, Do What You Love: And Other Lies About Success and Happiness

- What Demoralization Does to Teachers

- Claire Cain Miller, Women Did Everything Right. Then Work Got ‘Greedy’

- How I’ve Changed My Thinking On Burnout

- Pooja Lakshmin, The Tyranny of Self-Care

For today’s discussion, I’m curious about the state of your own industries and employers, passion-job or not. How are they protecting against becoming burnout machines? Alternately, how are they exacerbating the situation? And if you’re in one of the professions already on fire — do you see a way forward, or are you too deep in the firestorm to see anything clearly at all?

Subscribinggives you access to the weekly discussion threads, which are so weirdly addictive, moving, and soothing. You can find all previous threads here, if you need that enticement.

Plus! Subscribing is how you’ll get the Weekly Subscriber-Only Things I’ve Read and Loved Round-Up, including the Just Trust Me. It’s also a very simple way to show that you value the work that goes into creating this newsletter every week.

As always, if you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. (I process these in chunks, so if you’ve emailed recently I promise it’ll come through soon). If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Instagram here — and you can always reach me at annehelenpetersen@gmail.com.