Unplug the Classroom. Or Reboot It. Just Don’t Do Nothing.

Length: • 24 mins

Annotated by Mark Isero

Some content could not be imported from the original document. View content ↗

The pandemic transformed multiple aspects of K-12 education into political gasoline. Since 2021, books have been banned by the thousands from school libraries. Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, a former teacher, burnished his national profile by capitalizing on his state’s “Don’t Say Gay” legislation, which limited what teachers could say in class about sexual identity. Glenn Youngkin unexpectedly won the governorship of Virginia by promising parents more control over what children get taught. Textbooks and curricula are under hectic scrutiny. School board elections—usually the sleepiest backwater of American democracy—have frequently become a matter of widespread interest. Yet many of these conflicts are curiously out of sync with the actual experience of kids—who, as digital natives, have ready access to many more kinds of information than happen to be sanctioned by school syllabi. The moral panic about whether Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved is too disturbing to be allowed in school libraries comes at a moment when most American children play violent video games and are exposed to online pornography by the age of 12.

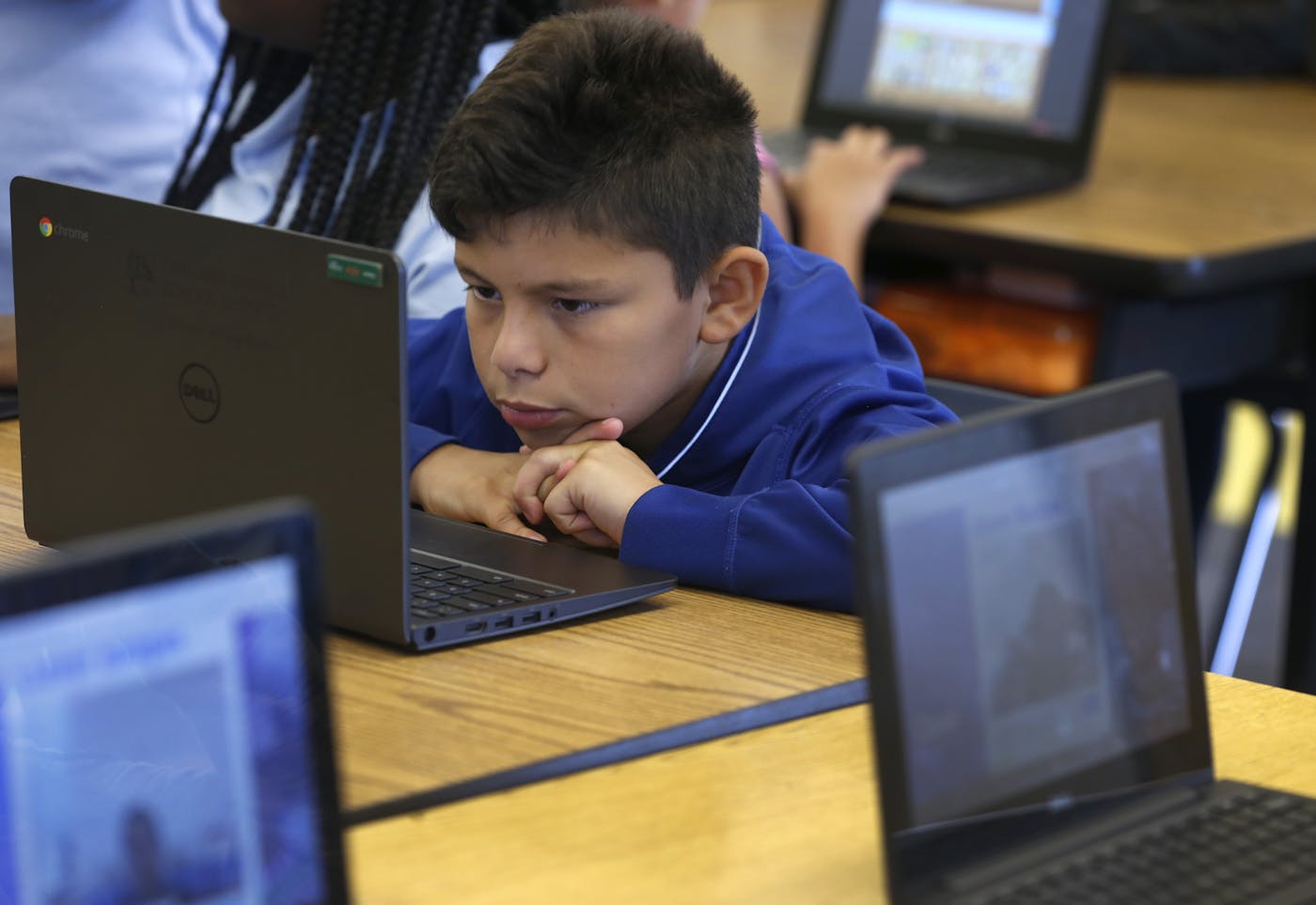

These flashpoints are but symptoms of a much larger collision between the digital revolution and our basic expectations of what is good for young people. If it put an end to the fantasy that children can be educated by just a tablet and an internet connection, the pandemic also introduced near universal access to and acceptance of online screens in schools. Ninety-four percent of school districts provide students with digital devices; well over half of all U.S. classrooms have a digital display in them. At the same time, an accruing body of research links screen time to depression, anxiety, stress, poor sleep, deteriorations in physical health, and other effects adverse to kids’ well-being. American teens spend an average of eight and a half daily hours on some screen or other, even as pediatricians recommend no more than a quarter of that. Ninety-five percent of American teens aged 13 to 17 use social media, despite 46 percent of them feeling the worse for it. We are fond of saying that tools and technology are neutral; a hammer may be used for good or ill. But, in the face of evidence about their addictive character—the World Health Organization, for example, now recognizes “gaming disorder” within its International Classification of Diseases—certain digital devices call to mind not so much hammers as hits of cocaine.

Indeed, it’s becoming apparent that the use of these devices is at odds with education itself. A slew of research has measured the effects of cell phones and other screens on children’s capacities to comprehend what they read and to concentrate in general. In one study, Arnold Glass, a professor of psychology at Rutgers, showed that classrooms in which students divide their attention between their studies and a screen used for fun do worse as a whole—that is, sheer proximity to distracting screens lowered grades for all students, whether they happened to be the users of a device or not. In another study, Glass demonstrated that doing well on one’s homework has yielded diminishing returns for digital natives. Over the course of 11 years, he measured an increase of about 40 percentage points in the portion of students who did well on homework assignments, but poorly when tested on the same information—presumably because they are helping themselves to digital aids to complete their assignments. “If you have a question, and you look up the answer” on the internet, Glass told me, “a week later, you will remember neither the question nor the answer.”

Schools and lawmakers have made some gestures toward addressing these problems. Tennessee, Indiana, and California have passed legislation allowing schools to limit or ban cell phone use during class hours. Florida and Utah legislators have advanced or passed bills that would restrict children under a certain age from having a social media account; Florida also now requires public schools to forbid students from using cell phones during instructional time and to teach “how social media manipulates behavior.” New York City has designated social media a “public health hazard” and sued the largest platforms for their effect on children’s mental health. More than 200 school districts have filed lawsuits against social media companies for their role in exacerbating teen mental health crises. The White House recently designated a new task force to protect youth mental health, safety, and privacy online. There is near consensus among both parties that cell phones and social media pose a grave threat to young people: the equivalent of a bipartisan unicorn.

The trouble with these expedients is that they don’t come near to addressing the scope of the challenge the digital era poses to education as a whole. Social media and cell phone use during class are just two components of a culture saturated with screens. More than 90 percent of American teens have a smartphone by age 14. Banning the devices from class might be an achievement approximately as momentous as prohibiting students with a fully fledged cocaine habit from consuming it while in the presence of a teacher.

Meanwhile, despite the fundamental shifts in our information environment, K-12 pedagogy and curricula have changed relatively little. School still takes the same number of years and covers most of the same disciplines. Much as they have for decades, teachers still mostly stand at the front of a classroom of 20 to 30 students and still mostly explain information from textbooks, comprehension of which is still mostly evaluated by means of the 112 standardized tests that the average American student will take by the end of high school. Kids equipped with state-of-the-art tech are still called on to memorize content and to perform the three “r’s” on tests—all in a world in which automation, search engines, and data exchange take the edge off the need for reading, writing, and arithmetic at high levels of proficiency. (When was the last time you performed long division by hand?) An education that asks children to sit obediently at their desks, absorbing facts or competencies they are then called on to produce on standardized tests, makes sense for the training up of a nineteenth-century bureaucracy. It is wholly inadequate today.

Either school should take seriously the ways in which ordinary digital practices are a threat to mental health and learning and teach children how to genuinely pay attention, or it should fully optimize for the digital world and prepare students who are suited to the digital economy. While it would be nice if school could achieve both objectives, it is doubtful that it can: Screens are either a wholesale threat to how kids think or they are not; school should either prepare students for the digital future as thoroughly as possible or develop another mission. The aims of attention and economy are incompatible, the trade-offs incommensurable. It is a question of choosing the best of one world or the worst of both. School must become tech-wary or tech-forward—or collapse into irrelevance.

Tech-Wary

A tech-wary education might proceed in a few different directions. For instance, rather than ignore digital realities, it could introduce students to them gradually, delaying the arrival of screens in order to provide some haven for the development of emotional and attentional capacities. The point would be to help students become moderate and mindful users. Or curricula might be organized around providing students with manual and domestic skills not available in digital terms. The point would be to teach students to work with their hands and to attend to material reality of the sort that would help them be makers and doers (rather than virtual users). Or—in the face of concerns about the influence of social media on teens’ mental health, about cyberbullying and online harassment, and about whether social media platforms lend themselves to the sexual exploitation of minors—curricula might focus on fostering offline socialization and habits of mind. The point would be to give children the chance to grow up buffered from the withering gaze of followers, trolls, and creeps, on the theory that young people are readier to reckon with their digital predicaments once they have figured out some baseline of face-to-face civility.

Not all these objectives are compatible. It’s hard to see, for instance, how one would prepare students to be mindful users of technology while also teaching them to ignore it. But a few schools are beginning to work out these lines of thought in practice.

Waldorf schools—founded in the early twentieth century on the inspiration of the Austrian esotericist Rudolf Steiner—long predate the digital age. They do not offer a uniform curriculum, but some have started to adapt their educational philosophy to address contemporary concerns about attention and mental health. The Waldorf School of the Peninsula in Santa Clara County, California, for example, offers a moderate, “slow-tech” approach. It has been of periodic interest to the media as a tech-cautious private school that serves a high-tech population in Silicon Valley. (Roughly three-quarters of the students at the school come from families who work in tech.) While the K-12 school cannot control what happens at home, parents receive guidance about delaying kids’ use of digital media until seventh or eighth grade, at which time screens are gradually worked into the curriculum with well-defined instructional purposes. Beginning in sixth grade, a program called Cyber Civics introduces students to general conversations surrounding the uses and abuses of tech. In twelfth grade—once students are up to speed with all kinds of digital media—a class on digital literacy addresses how technology changes us as human beings.

The Waldorf approach presumes that children who are given the space to develop at their own pace—through play, offline socialization, and hands-on activities—will gradually learn how to be responsible users of technology. “We are not trying to educate children who will be misfits,” said Monica Laurent, a faculty member at the school. “Little children really learn by doing things, by experiencing things, by sensing things, by imitating other children or adults.” In Laurent’s experience as a teacher, children who wait longer to use screens are more emotionally and socially mature, better able “to interact with people and to face challenges when they come to them.” Neurologically speaking, the rationale is solid: A brain less accustomed to easy dopamine hits may be better primed to tolerate discomfort or hard work. But it’s unclear whether this curriculum is powerful enough to inform students’ extracurricular uses of technology, or whether its main benefit is to secure a semblance of wholesomeness that most appeals to their parents.

The Clear Spring School, a small private, K-12 school in Eureka Springs, Arkansas—an artsy but by no means affluent town—offers a second kind of response to the question of how school should work today, with an emphasis on crafts and labor. Students take classes in sewing and art; they prepare meals; they build things in the woodshop; and they go on semiannual camping trips. “You understand things a lot better if you’ve done something,” explained Doug Stowe, a woodworker and author who taught at Clear Spring School for 20 years. While students have subject teachers, the curriculum does not proceed along disciplinary lines. Crafts are occasions for students to learn the underpinnings of what they are doing: A woodshop project is used as the means of working out math and geometry problems; a meteorology class integrates literature; a field trip teaches students about geology and economics; and so on.

There is no long-standing technology policy here, nor is the curriculum consciously anti-tech—students might use software to map the location of certain kinds of trees in the neighborhood, for instance. The point is not to oppose or take time off from digital technology, but to orient students toward kinds of learning powerful enough to be actually preferable to virtual experiences. It’s easy to put cell phones away, Stowe added, “when you have real things to do.”

This prepares students for the kinds of work they will likely do—filling out Excel spreadsheets and quarterly HR reports—not by accustoming them to it early but by showing them what else there is. “The best way to prepare for the dismal life is to have a life of joy at the side,” Stowe quipped. If a screen is addictive, the goal is to bring students into contact with a reality nourishing enough to inure them to it. There’s been a proliferation of other similar “portable” programs, like Maplewoodshop in New Jersey, Building To Teach in Virginia, and All Hands Boatworks in Wisconsin, which teach math and science skills through craft projects. Such curricula aim to answer to the digital age by trying to change the subject altogether.

Of course, these schools do not have a monopoly on after-hours or socialization. Some pockets of Christian parents have accordingly started taking a “Postman Pledge” (named for technology critic Neil Postman) to delay or limit their children’s use of smartphones and social media, on the theory that the problems are steep enough that they can only be addressed by whole communities of like-minded skeptics. But the only educational institutions in a position to control students’ attention whole hog are those as absorbing and totalizing as digital technology itself: boarding schools.

At Midland School—a 90-year-old private boarding high school set in bucolic Los Olivos, California—students perform various forms of manual labor, play sports, ride horses, and spend a lot of time outdoors, in addition to a standard curriculum. The campus buildings have a log cabin, summer-camp aesthetic. The school is not organized around the uses of technology, but it has inevitably had to make decisions about how to limit or monitor devices so as to minimize disruption to its program. Students may not bring their own cell phones to school. (Cell phone service on campus is scant, for that matter.) Phil Hasseljian, the director of IT, oversees their internet use. TikTok and other sites are blocked altogether; Facebook, Instagram, and Pinterest are blocked only during the school day. The internet is shut off at night. “There is a built-in 10-hour pause every day,” explained Christopher Barnes, the head of school.

The students I encountered there—flushed with the exertions of building an outdoor shower and unloading a truck—were basically very happy with these arrangements, which they compared favorably to previous experiences. E.Z., a sophomore, said that at the school he used to attend, “it felt like kids were less connected to each other.” (Midland doesn’t share students’ full names with the press.) Annika, a senior, agreed. “Everybody would use their phones.... It felt very dystopian.” No one seemed to miss their phone.

Plenty of anecdotal evidence suggests that graduates have a more conscientious relationship to technology than average. On the other hand, students expressed some ambivalence and anxiety about their own position. Z. said that because adults at the school aren’t subject to any digital restrictions, it could feel as though the students were watched over by “wardens” who weren’t “subject to the same rules” that the students were. Annika admitted that she binges on screen time whenever she leaves the school on a break; she worries about not knowing how to moderate her use of tech after graduation. Hasseljian—who is in charge of keeping tabs on students’ internet access—“is like God,” she joked.

These are the grouses of young people who are bound to push against established (and in loco parentis) limitations. But the dependence of low-tech schooling on high-tech surveillance is a telling one. Hasseljian uses an algorithm to block illicit searches and—in cases of students who are repeat offenders or are struggling with academics—occasionally deprives them of recreational internet access altogether.

If screen time really is more like cocaine than like a hammer, it’s conceivable that responsible use is just not possible without centralized, authoritarian intervention. It is hardly an accident that the country that most thoroughly limits kids’ screen time is China, which is expressly concerned with the demoralizing effects of what a regulatory agency called “minors’ internet addiction.” Chinese children are forbidden from bringing cell phones to school; classroom time spent on screens is limited to 30 percent of the whole. Since 2021, strict limits govern when and for how long children may play video games each week. Regulations put in place in 2023 require children’s smartphones to operate in “minors’ mode,” which monitors the quality and quantity of permissible screen time according to the child’s age and the time of day. Access is shut off at night. If any of these parameters are infringed, the device automatically closes all apps but those specified as necessary or as exceptions by parents. The ambition and fastidiousness of these regulations are fairly breathtaking. Parents everywhere may view this regime with more envy than they are willing to admit. With a big brother like this, who needs Phil Hasseljian?

Tech-Forward

So much of the hype surrounding tech in schools concerns smartphones and social media that it’s easy to forget the other devices that come into play in the classroom. A tech-forward education might have several priorities in view. It should actually prepare students for the digital workforce from a young age, accelerating the pipeline from K-12 to a professional vocation, wasting less time on irrelevant subjects, and making digital professions accessible to students from all backgrounds. It might be pursued not simply for economic ends, but to liberate students by making their digital world more legible to them. If automation is about to render all kinds of rote tasks obsolete, digital technology should provide students with a way of expressing authentic human aims. And technology might be used to provide much more nuanced and tailored feedback to students than teachers are ordinarily in a position to give. The point would be to use digital technology to serve a pedagogical end by doing what it does best: measuring, quantifying, and aggregating data so as to engage each student’s capacities precisely where they are.

As in the previous cases, it is doubtful that all these priorities are compatible with one another. For instance, while just about everyone—tech-wary and tech-forward—touts the value of childhood creativity, there is a clear difference between making it a goal of education and paying it lip service as a talking point subordinate to other aims. And none of the tech-forward options I looked at expressed particular concerns about the compatibility of screens with attention spans or mental health. But it’s also worth noting that, while most tech-wary schools are private, many tech-forward institutions are in contact with the brute realities of the digital divide and the U.S. public school district.

Burlington school district (in the greater Boston area), an early adopter of the national Computer Science for All initiative, provides computer science education from pre-K through twelfth grade. The district was the first to give iPads to all high school students; now students of all grades get one. Children who do not have internet access at home are provided with Wi-Fi hot spots that connect to the district’s internet service provider. “The goal is to get kids ready for an environment that they’re going into,” Dennis Villano, the director of technology integration for the district, told me. The district, unusually, has no cell phone ban and does not block YouTube or social media. When kids start using technology at a young age, Villano argued, they are more likely to treat it as “just a tool” rather than as “something for fun.”

Technology is introduced into the K-12 curriculum in a graduated manner. In elementary school, a team of digital learning coaches teaches lessons meant simply to get the kids excited about technology and computational thinking. Every middle school student takes three years of computer science, when they are introduced to data science and programming languages like Python. Once they reach high school, students are encouraged to join the Innovation Career Pathways program—a grant-funded program started by the state of Massachusetts that supports high school students who want to focus on a high-demand industry, like data science or cybersecurity. More than two-thirds of the seniors at Burlington High School sign up for it.

While this curricular emphasis carries a hint of the indoctrinatory, Villano insisted the goal is not to force people into a narrow range of careers—“a computer scientist could be an artist, a musician, or someone in the medical field,” he pointed out. But the Innovation Career Pathways program has a clear vocational purpose, culminating in an internship at a tech company like iRobot or Adobe. When it comes to advancing more equitable outcomes for students of color, from poorer backgrounds, or those for whom English is a second language, the confluence between school and industry can seem largely beneficial.

Still, not all parents are likely to be keen on the idea that their children should be trained to be cogs suitable to a tech juggernaut’s machine. Any decent educational program should speak to concerns about its instrumentalization. Mitchel Resnick, a professor of learning research at the MIT Media Lab, offers one answer to the question of how a tech-forward education might develop children’s expressive capacities. Resnick is one of the creators of Scratch, a visual programming language that is designed to introduce kids between eight and 16 to the elements of coding in a playful way. Widely adopted by schools and other institutions, the free program has a pool of about 128 million registered users. He is also a co-founder of the Clubhouse Network, a series of 148 free, out-of-school learning centers, in which children from lower-income communities can creatively explore technology with guidance.

Resnick’s approach rests on the premise that digital technology is one means of opening up the world for children. While he sees some value in learning coding as a marketable skill, this is not the point of Scratch. Coding is more than that, “a way for people to be able to express themselves.” And all children should have the opportunity to engage with it. In other words, Resnick sees digital technology as one medium among many. Excessive use of it is harmful in the way excessive time spent on any childhood activity might be: “If kids spend all day looking at picture books and never go outside, that’s not a good thing” either. He insisted that we “focus less on minimizing screen time and focus more on maximizing creativity time.”

A central principle of Resnick’s thinking is that the nature of work is itself changing so quickly that new kinds of capacities will be necessary to succeed. Because there is no specific body of knowledge that would remain relevant during the time it takes to raise a child, education, he argued, should focus on teaching children to be creative and collaborative under all circumstances. “Providing people a chance to design, create, experiment, and explore leads to a meaningful, fulfilling life,” he said. “Those same traits will be the core of thriving in the workplace as well.” This might seem like an awfully happy coincidence, and Resnick’s idealism sometimes seems so unblinking as to be dewy-eyed. But he admits that this best-case scenario is not inevitable. “A lot of the education system,” he acknowledged, “is not being set up that way.”

Whichever way this goes, and beyond the question of what children learn, technology is already altering how they learn, with digital personalization. The purpose of this personalization need not be to replace teachers, but rather, as at Quest Academy, a K-9 charter school in West Haven, Utah, it can be to optimize their oversight of students.

Animated by its charismatic middle school principal, Nicki Slaugh, Quest offers computer science from first grade; it’s required in sixth through ninth, where students learn coding, digital media arts, and gaming. Students are asked to leave their cell phones or other devices in pockets at the door for the duration of each class period. In each of the half-dozen classrooms that I visited, kids sat facing different directions, doing their own thing on a Chromebook. There is no “front” of the room, though a big-screen monitor on each classroom wall announces the day’s general topic. Students start each period by identifying where they are on a rubric of learning objectives, which vary in level from “emerging” to “mastering” and “extending.” The teacher and teaching assistant move around the room, working with individual students or in small groups.

The setup allows teachers to scrutinize data about students’ performance in real time and allows students to move through some parts of the curriculum at their own pace. “With technology ... I’ve been able to customize and personalize my lessons to meet the needs of kids,” Slaugh explained. Seventh graders with higher aptitudes might already be working on ninth-grade math (which will, in turn, free up their trajectory through high school). Conversely, students who struggle are easily identified as needing more remedial work and attention. While Slaugh insists that no shame is attached to this, it’s clear that personalization has the consequence of sorting the highest from the lowest achievers much more efficiently; it makes disparities between students more visible. Each teacher also has discretion over how they program technology into their classroom. Martin Ji, a newish history teacher, explained to me that MagicSchool AI lets him summarize the readings, as well as calibrate those summaries to different levels. Brylee Nelson, an English teacher, uses Nearpod to let students write out their learning objective and then vote on the best version of it. Quest has handily beat state testing averages year after year.

Quest’s successes likely have something to do with the school’s relentlessly upbeat atmosphere: Teachers greet their students at the door for each period, and students who reach proficiency on an educational standard are applauded by the whole school as the fact is announced over the intercom. The optimizing of technology relies on an ethos of cheer that seems borne of both real human connections and an extensive amount of monitoring and data surveillance. Cameras installed throughout the school can zoom in on every sight and sound—which Slaugh says makes disciplinary disputes rarer. Students report on their mood each class period; their report card includes both academic grades and “citizenship” scores for behavior. Parents have online access to their child’s progress. And the predominance of digital assignments means that teachers have instant access to how students are doing and—with a software called GoGuardian—to what they are looking at on-screen at any given moment. Nelson showed me the panopticon of student screens during class. When one of the students opened a tab for non-scholastic reasons, she simply shut it down from her own device. That was that. While students work on their assignments, they will also ask her questions over a chat. “Some of them would rather chat than walk over to me,” she added, smiling. “It’s a generational thing.”

The Choice

My aim here is not to call a winner between tech-wary and tech-forward alternatives. The way the wind is blowing is clear, in any case—tech is one of the most valuable industries in the United States and computer science one of the fastest-growing majors. It is also unlikely that all students would benefit from a single answer to the question. But it would be dangerous to ignore the magnitude of what is at stake.

One obvious area of difference between tech-wary and tech-forward concerns the status of childhood. Tech-wary schools tend to see childhood as a stage of growth at once essential to human development and in need of a protective enclosure from online sexualization, socialization, and commercialization. “A cell phone in many ways is a portal to an echo chamber,” said Joy McGrath, head of St. Andrew’s School, a Delaware boarding school that limits students’ cell phone and tech use. Being educated offline allows kids the freedom not to grow up quite so quickly. At St. Andrew’s, she pointed out, teenagers still play. Play, she argued, “is incredibly important for high schoolers,” and its loss is a significant factor in teen mental health.

It’s notable that the leading tech-wary institutions I examined are inspired by pedagogical models formulated a century or more ago. They are also private, as a rule. Boarding schools like Buxton in Williamstown, Massachusetts; Midland; and St. Andrew’s—as well as the other tech-wary schools I looked at—recruit and offer need-based aid to students from all backgrounds but nonetheless are ultimately available only to a tiny fraction of the population. It’s somewhat strange to score the matter of their privilege, since the cost of these schools’ technical apparatus is likely insignificant compared to those of a tech-forward education. The privilege is one of the close oversight that students receive from adults, as well as of what tech tycoon and guru Marc Andreessen has recently dubbed “reality privilege”—the privilege of those whose offline lives seem better to them than those they access online.

Besides the mission of preparing students for the future, higher-tech options usually come with the justification that they will provide equitable outcomes for more students. And on the one hand, such an education does offer the possibility of feeding students into the digital workforce, thereby providing them with professional opportunities that are still mostly taken up by white men from college-educated, English-speaking backgrounds. Perhaps childhood (like reality) has become an optional privilege, such that students should avail themselves of the opportunity to skip grades and—labor laws permitting—to take a job earlier than 18. Once kids in his district start meeting with industry leaders, Villano said, “they could easily be given a job in high school.”

On the other hand, the pandemic made it clear that access to gadgetry unaided will actually increase inequality. The gap between test scores in low-poverty and high-poverty elementary schools grew by about 20 percent in math and 15 percent in reading during the 2020–21 school year alone. The inescapable reality remains that students most benefit from school with extensive and capable adult attention, which is itself scarce. The 2024 National Educational Technology Plan distinguishes between “access” (i.e., whether students have a device available) and “use” (i.e., whether they are taught how to best employ it) for this reason. More than just putting devices into schools, it is a matter of changing how the devices are taught. “Human development at any kind of scale is incredibly difficult and complicated,” said Justin Reich, director of the Teaching Systems Lab at MIT. “Improvements come through a real shoulder-to-the-wheel, long-term, committed approach, rather than silver bullets.” In other words, there is no hack for good teachers.

Nevertheless, some districts have pulled off significant digital transformations. Over 15 years, Talladega County Schools in Alabama drastically improved graduation rates by introducing technology programs and training teachers to use them. But comprehensive data is lacking about just what computational skills used under which conditions can make a measurable difference to students’ socioeconomic mobility. And when you consider the tremendous economic incentives that tech companies have in the educational industry—in selling schools billions of dollars’ worth of hardware and software (which require periodic upgrades) and in training up future users of Apple or Google products—the question of who currently benefits most from the highest-tech arrangements looks different.

But the single starkest difference between a tech-wary and a tech-forward education might be the place and purpose of the book. Neither of the English classes I observed at Quest involved any books. In Nelson’s class, some students were working on analyzing two different articles, as well as on a Sprite ad featuring Drake. “We provide rigor and relevance,” Slaugh said. In Gigi Zavala’s English class, students were reading three different online articles—one on McDonald’s, one on malls, one on solar pizza ovens—but there was no group discussion or deeper hermeneutical engagement. “We’ve killed the novel as a group [activity],” Zavala told me.

The boarding school teachers I spoke to, by contrast, commented on how greatly cell phone bans improved the quality of classroom discussion. John Kalapos, co-director of the Buxton School, described the marked improvement he observed in his seminars on literary texts after the school banned smartphones. “Now we have the ability of engaging in more long-form discussion and ideas,” he said. It is very hard to quantify, standardize, or put a price on such discussions.

No matter where you stand on the role of screens, the evidence is incontrovertible that school is not going that well. More than half of American adults read below the equivalent of a sixth-grade level. Fewer than half are able to name the three branches of government. Only a small minority think that high school graduates are well prepared for either work or college. Eighty-six percent of schools report difficulties in hiring personnel. The number of people completing teacher prep programs has dropped by about 35 percent over the last decade. The United States spends far more per student than other countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, while its proficiency levels are only about average for that group.

But our current crises in education are not of resources, but of purpose. So long as we fail to answer the question of school’s meaning for the digital age, education—and public education in particular—will continue to lurch haphazardly between technological innovation and curricular inertia. Indeed, the question is each day being answered for us, heedless and regardless.

Tech-wary and tech-forward are not simply pictures of two educations but of two kinds of human beings and two kinds of Americas. How we evaluate their successes will depend on what we care to make count: If the privilege of reality is the source of a new digital divide, shouldn’t we be doing everything in our power to afford it to everyone? Can we simply concede that big tech has wrecked the possibility of mental health, attention, and childhood per se? Conversely, if our tech race with China has existential stakes, shouldn’t we do everything in our power to ensure that school is training up the most efficient digital workforce in the world (just as the launching of Sputnik galvanized public education with a new STEM emphasis)? Shouldn’t we make sure that children’s formative years set them up to succeed in the world they’ll live in, instead of wasting so much of their time along the way with origami cranes and information they don’t recall?

It’s worth acknowledging the partisan divide that roughly maps on to these two pictures. The states and public school districts with the most stringent restrictions on kids’ social media access and with the greatest emphasis on parental control tend to be more Republican and culturally conservative. Progressive criticisms of digital technology, on the other hand, tend to focus on the plutocracy of Silicon Valley and uneven access to technology as a source of disparities of opportunity and equity. These political alliances make sense, if one considers that the conservative impulse to limit access to screens is often connected with the desire to limit kids’ exposure to ideas deemed upsetting or dangerous, often connected to gender and race. But the alignment is not fully warranted. Limiting access to screens is not necessarily limiting access to ideas; if an onslaught of screens degrades their capacity to think cogently and consecutively about complicated questions, then it matters very little whether kids adopt the right opinions or encounter transformative views, since they will not be able to adequately evaluate or expand on them. The fact that so much of our discussions are about “exposure” to ideas rather than about thinking through them is itself a symptom of this mistake. Why is there no tech-skeptical left to take up this issue?

All parents should be troubled by the worst implications of the digital attention economy for their children. But if, as a nation, we can agree that the protection of childhood should trump the imparting of a digital edge in public schools, then we should also acknowledge that children from some backgrounds will bear the economic cost of this decision far more than others. And if we agree that equity is our highest goal and should be pursued in digital terms, then we should concede that it will be paid for in some children’s mental health and capacity to read attentively. It is a cruel choice to have to make.

Yet so long as we do not make it, it will be so much the worse for all of us. Even if their answers are incomplete, the schools I’ve discussed are nonetheless in better shape than the rest: At least they’re attempting to provide a satisfactory answer to the digital revolution, which goes on anyhow. If school is to be anything more than part-time childcare, we must either unplug our children’s education or reboot it. Not choosing at all will mean surrendering our minds and our kids’ to the lie that characterizes so much of our technological sleepwalking: that it is too late, that we must follow along behind technological development instead of stepping up to shape it. Are we ourselves still able to wake up and pay attention to what our kids most need?

Antón Barba-Kay is a humanities professor at Deep Springs College in California and the author of A Web of Our Own Making: The Nature of Digital Formation.