Engineering Leadership Tactics: Circle of Influence

Length: • 4 mins

Annotated by JMP

How to achieve change with less effort?

When working as an Engineering Manager (EM), a significant part of your time is spent attempting to improve the status quo. Continuous improvement is part of the day-to-day in tech companies, and more likely than not, there is much to improve.

While we have discussed high-level tools that an EM has at their disposal, I want to touch on a few tactics and principles I have consistently used in my career. One of them is the concept of your circle of influence.

The Focus Challenge

A consistent challenge for managers is where to put their energy. There is always too much going on, and there are no clear rules about what to focus on. Ultimately, time prioritization is part of the role.

Besides the lack of clarity, there are endless ways to get distracted. Any company will have many improvement opportunities (i.e., things that are not going as well as possible), and it’s pretty easy for someone to get lost while trying to do a good job. Ironically, this situation can worsen if an EM is good at implementing successful improvements. The success will lead to people reaching out and asking for help, creating even more chances for distraction.

Spreading Thin and Burning Out

This happened to me a while ago when joining a new company. As a new manager, I was keen to demonstrate results and soon had a few wins within my teams. I was able to improve how they worked, and that led to recognition by different people within the company.

All of that was positive. However, I was eager to continue and started being asked to look (and volunteer) into more team and organizational problems, some of which were outside my role’s purview. I was soon becoming a fixer for many issues and excited about the opportunities for impact.

It didn’t end up well. With more items in flight, it wasn’t long until I stopped being effective, and the usual response of working harder wasn’t effective anymore. I ended up failing at many initiatives and burning out simultaneously.

Your Circle of Influence

The situation above looks evident in hindsight, but it’s harder to navigate when you are in the middle of it. I believed I could achieve everything I aimed at and forgot to think about a very useful practice in my career as a consultant: thinking about your circle of influence.

The Circle of Influence & Concern is not a new or original tool, but it was instrumental when I was consulting. The main rule was that it was beneficial to focus on the areas I could control, especially when a consultant has limited or no authority in their work environment.

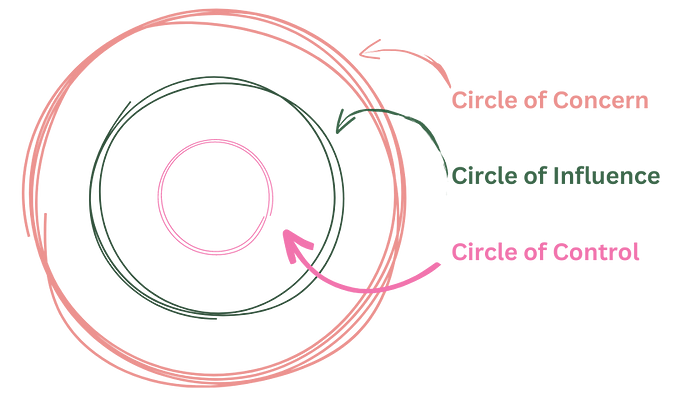

The summary of it it’s pretty simple. There are three main areas someone should be aware of:

- Circle of Control: what you have authority on. As a manager, this would be their team, for example.

- Circle of Influence: areas where your opinion is part of the decision-making. That could be your broader division or how product managers work with your team.

- Circle of Concern: areas you are concerned about but have limited capacity to influence. How the broader organization runs would be an example of that.

With that in mind, if someone wants to increase their chances of success, they should work within areas they have more control and influence.

Influencing as an EM

As an EM, acting outside your area of control is tempting. There are many opportunities for it, and making a broader change is an impact everyone likes to have. “Can we improve the way we do X at the company? That would have really positive consequences!”

The advice I regularly give to myself and others is to consider your circle of influence when approaching any problem. It is easier to improve areas where you have authority and go broad from there than the other way around. In other words, if someone wants to achieve a broader impact, they should act within their area of control first.

That’s because the best path to extending the circle of control and influence is to increase the confidence that others have in their capacity to deliver results. To obtain that, they should show what they can do when they have control of a situation. For example, if an EM’s next growth step is to manage multiple teams, they can demonstrate the results they can achieve within the team they are managing first, and then an increase in responsibility should follow that.

Aren’t there exceptions?

This doesn’t mean managers should never act in areas outside of their control. There are certainly situations where aiming for broad changes is the best approach. But they should consider how acting in that manner will consume more energy and take more time, and consider it when deciding to take action.

Ultimately, an EM should be mindful of where their focus is and at which level they are trying to act. It will lead to less work and more results.

If you have found this content interesting, this post is part of a series on Leading Software Teams with Systems Thinking. More broadly, I write about leading effective software engineering teams. Follow me if you are interested in the area.