The cult of Obsidian: Why people are obsessed with the note-taking app | Obsidian崇拜:为何人们对这款笔记应用如此痴迷

Length: • 11 mins

Annotated by howie.serious

The indie darling rejects everything you know about modern software. And its strategy is working.

这个独立游戏宠儿拒绝了你所知道的所有现代软件。而且,它的策略正在奏效。

[GIF: Obsidian] [GIF: 黑曜石]

A few years ago, Nick Milo was using a folder full of plain text files for notes when he found out about Obsidian.

几年前,Nick Milo在使用一个装满纯文本文件的文件夹做笔记时,他发现了Obsidian。

The app had just launched in beta, and was getting some buzz on a productivity forum that Milo liked to frequent. Obsidian gave structure to text files in a way that resembled more popular apps such as Notion and Evernote, and it didn’t take long for him to get hooked on the app.

这款应用刚刚在测试版中发布,并在Milo喜欢的一个生产力论坛上引起了一些热议。Obsidian以一种类似于Notion和Evernote等更受欢迎的应用的方式给文本文件提供了结构,他很快就对这款应用上瘾了。

“Immediately, I recognized that they had cracked the code,” he says.

“我立刻就认出他们已经破译了这个密码,”他说。

Milo has since become one of Obsidian’s most outspoken users, with a popular YouTube channel and e-course that calmly explains not just how to use Obsidian, but why. (A popular comment on his first video: “This wasn’t a product walkthrough. This was a guided meditation.”)

自那时以来,Milo已经成为Obsidian最直言不讳的用户之一,他拥有一个受欢迎的YouTube频道和电子课程,不仅平静地解释如何使用Obsidian,还解释了为什么使用。 (他的第一个视频上的一个热门评论:“这不是一个产品演示。这是一次引导冥想。”)

He’s not alone in seeing the light: Obsidian estimates that it has one million users, and its Discord channel has more than 110,000 members, who use the app for everything from task management and bookmarking to organizing their daily thoughts. On Reddit, Obsidian ranks in the top 5% of communities, with 94,600 members. All this happened without any venture capital backing or outside investment.

他并不是唯一看到希望的人:Obsidian估计它有一百万用户,其Discord频道有超过110,000名成员,他们使用这个应用程序进行从任务管理和书签到组织每日思考的所有事情。在Reddit上,Obsidian位于社区的前5%,拥有94,600名成员。所有这些都在没有任何风险资本支持或外部投资的情况下发生。

Obsidian’s grassroots success is all the more remarkable given that the app isn’t especially inviting to nontechnical users. While apps like Notion put all your notes in the cloud so you can instantly access them from anywhere, Obsidian gives users a folder full of files and puts them in charge of managing it. Using Obsidian also requires some familiarity with Markdown—a text-editing language with its own unique syntax—and leans on third-party plug-ins for features that are table stakes in other note-taking tools.

Obsidian的草根成功更加显著,因为该应用并不特别吸引非技术用户。虽然像Notion这样的应用将所有的笔记放在云端,以便你可以随时随地访问它们,但Obsidian给用户提供了一个充满文件的文件夹,并让他们负责管理它。使用Obsidian还需要一些对Markdown的熟悉——这是一种具有其独特语法的文本编辑语言,并依赖第三方插件来提供其他笔记工具中的基本功能。

But that nerdiness is also part of its allure: Once Obsidian endears itself, it’s hard to imagine using much else.

但是,那种书呆子气质也是其吸引力的一部分:一旦Obsidian让人喜欢上,就很难想象使用其他的东西了。

[Photo: Obsidian][图片:Obsidian]

Building the grassroots打造基层

Erica Xu and Shida Li started working on Obsidian in 2020 while quarantining during the pandemic. The two engineers had met at University of Waterloo, and had previously developed a task management app called Dynalist.

艾瑞卡·许和李诗达在2020年的疫情隔离期间开始研发Obsidian。这两位工程师在滑铁卢大学相识,并曾共同开发了一个名为Dynalist的任务管理应用。

In an interview with Ness Labs, Xu said she was scratching a personal itch. She had tried to create personal wikis for herself, but other tools such as MediaWiki and TiddlyWiki never clicked, and with note-taking apps, there was always one particular feature that wasn’t available or didn’t quite work as intended.

在接受Ness Labs采访时,徐女士表示,她正在解决一个个人问题。她曾试图为自己创建个人维基,但是其他工具如MediaWiki和TiddlyWiki从未引起她的兴趣,而且在使用笔记应用时,总是有一个特定的功能不可用或者并未按预期工作。

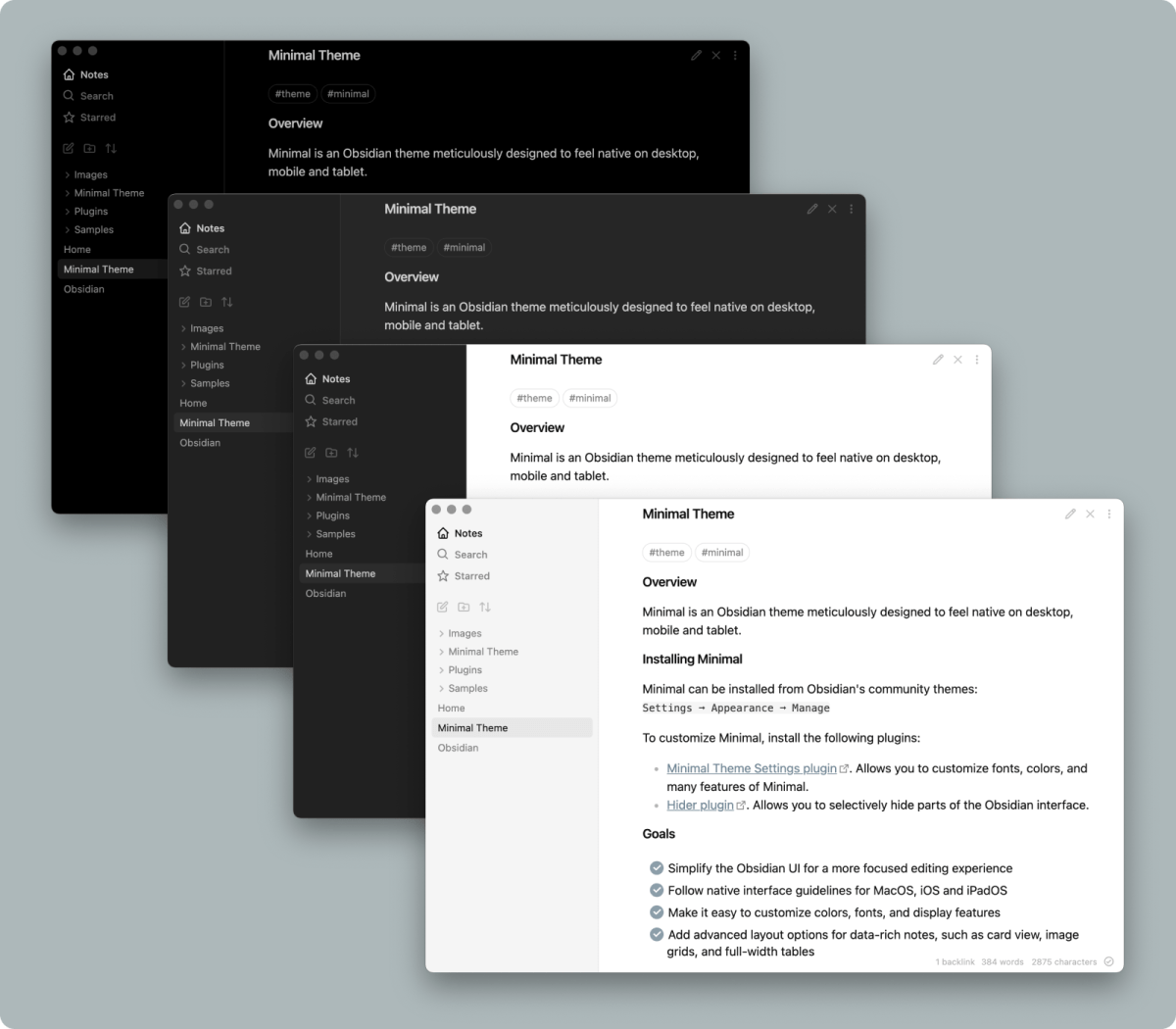

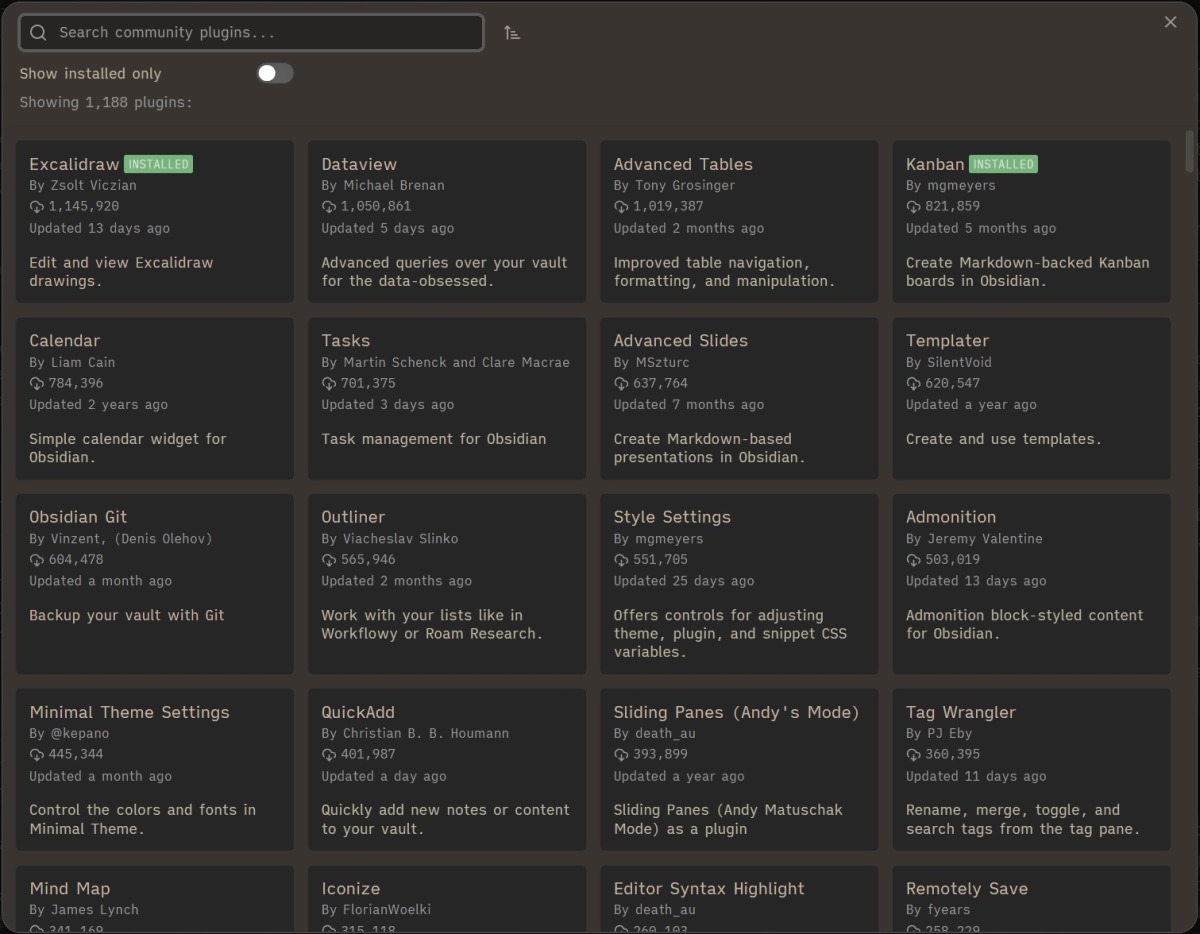

In a nod to extensible code editors, she came up with the idea of a plug-in system that Obsidian even uses for its core features. This allows users to replace elements such as the word count with third-party alternatives, or even bolt on new features such as kanban boards and freeform drawing.

她借鉴了可扩展代码编辑器的思路,提出了一个插件系统的概念,Obsidian甚至用它来实现其核心功能。这使得用户可以用第三方替代品替换诸如字数统计等元素,甚至可以添加新功能,如看板和自由绘图。

Xu and Li then turned to Discord, both to distribute early betas and spark the plug-in system. Speaking to Robert Haisfield, Li said he drew on his past experience as a gaming community moderator to set up Obsidian’s community as a welcoming space, with mods acting as role models.

徐和李然后转向Discord,既用来分发早期的测试版,也用来启动插件系统。李在接受Robert Haisfield的采访时表示,他利用过去作为游戏社区版主的经验,将Obsidian的社区建设成一个欢迎的空间,版主们充当了榜样的角色。

Eleanor Konik, a fantasy author who helps moderate the Obsidian Discord and writes a popular newsletter about Obsidian updates and plug-ins, says the result feels something like a mentorship program for aspiring JavaScript programmers. Especially in the early days, the developers would spend a lot of time not just making sure plug-ins worked properly, but that people were learning along the way.

奇幻作家Eleanor Konik,她帮助管理Obsidian的Discord,并撰写了一份关于Obsidian更新和插件的热门通讯,她说结果感觉像是一个针对有抱负的JavaScript程序员的导师计划。尤其在早期,开发人员不仅会花很多时间确保插件正常工作,而且还会确保人们在过程中学习。

“You just don’t get the kind of dudebro, single, angry, San Francisco, bent-on devouring-the-world kind of aggressiveness and posturing that you get from a bunch of 22-year-old hotshot developers,” Konik says.

“你根本无法理解那种来自于单身、愤怒、身处旧金山、一心想要吞噬世界的那种傲慢和炫耀,这种情绪通常来自于一群22岁的热门开发者。”科尼克说。

When the time came for Obsidian to expand its team, Xu and Li hired from within. For CEO, they brought on Stephan Ango, who co-founded and sold the packaging startup Lumi, after he developed Obsidian’s Minimal theme and helped out with their version 1.0 release last year. They also hired several other plug-in developers as engineers.

当Obsidian需要扩大其团队的时候,徐和李从内部招聘。他们聘请了Stephan Ango作为CEO,他是包装创业公司Lumi的联合创始人,并在去年帮助Obsidian开发了Minimal主题并参与了他们的1.0版本发布后,将其卖出。他们还雇佣了几位其他的插件开发者作为工程师。

“They’ve been slowly expanding the team, but they’ve been expanding from the userbase, which gives them more of a force multiplier, because the people they’re hiring really know the community,” Konik says.

“他们一直在慢慢扩大团队,但他们是从用户群中扩展的,这给了他们更大的力量倍增器,因为他们雇佣的人真正了解社区,”Konik说。

[Photo: Obsidian][图片:Obsidian]

Making it their own让它成为自己的

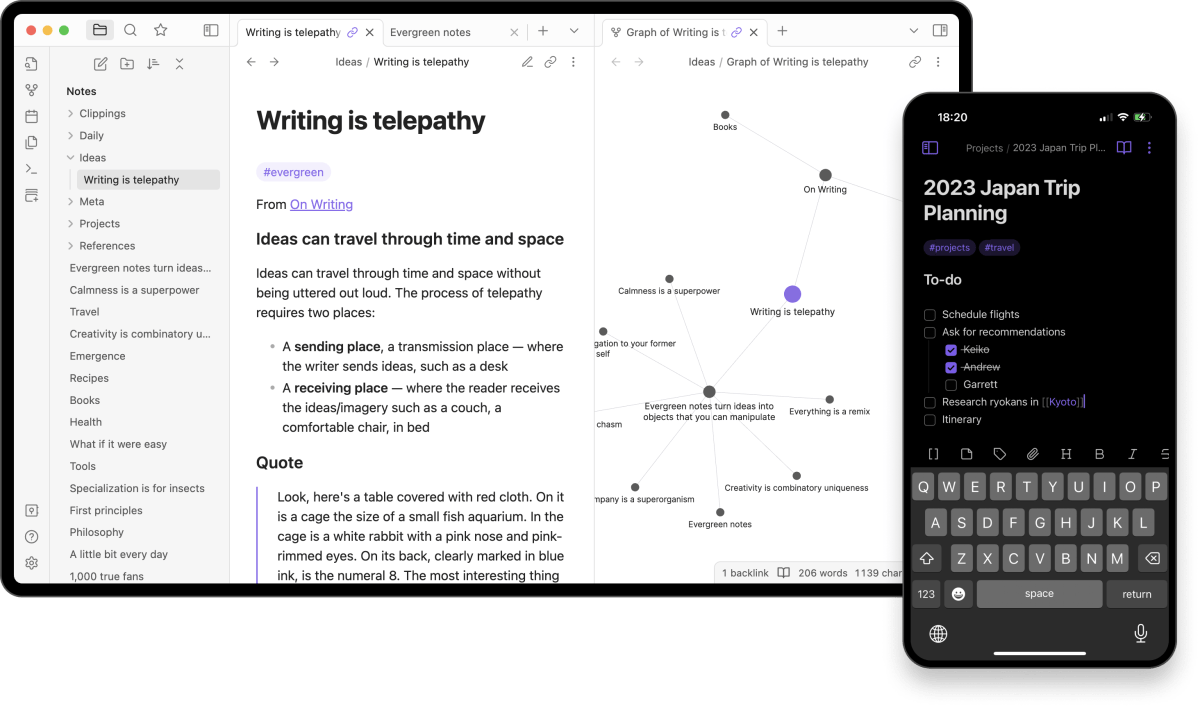

The bottom-up nature of Obsidian is also reflected in the app itself. Milo says one thing that drew him to Obsidian is how it’s not prescriptive about organization. In addition to a traditional folder structure, users can view a graph that shows all the links between their notes. They can also use the Bookmarks section arrange notes independently of their file system, Another recent feature called Canvas lets users arrange notes on a pinboard, alongside comments, images, and embedded web pages.

Obsidian的自下而上的特性也反映在应用本身。Milo说,吸引他的一点是Obsidian并不规定如何组织内容。除了传统的文件夹结构,用户还可以查看一个图表,显示他们的笔记之间的所有链接。他们还可以使用书签部分独立于文件系统来整理笔记。另一个最近的功能叫做Canvas,让用户可以在一个图钉板上整理笔记,旁边还可以放置评论、图片和嵌入的网页。

“With Obsidian, you can still have folders, you can do all that, but it allows a looseness, more of a bottom-up chaotic energy, where you can connect things even if you don’t know where that’s going,” Milo says.

“使用Obsidian,你仍然可以拥有文件夹,你可以做所有这些,但它允许一种松散性,更多的自下而上的混乱能量,即使你不知道这会通向何方,你也可以连接事物,”Milo说。

Obsidian’s approach has also made for some surprising converts.

Obsidian的方法也吸引了一些出人意料的转变者。

John Voorhees, the managing editor at MacStories, started using Obsidian a couple of years ago after being drawn to its local file structure, and both he and MacStories founder Federico Viticci have written extensively about their Obsidian setups since then.

MacStories的管理编辑John Voorhees在几年前开始使用Obsidian,他被其本地文件结构所吸引,自那时以来,他和MacStories的创始人Federico Viticci都对他们的Obsidian设置进行了大量的写作。

Obsidian is on some ways the opposite of a quintessential MacStories app—the site often spotlights apps that are tailored exclusively for Apple platforms, whereas Obsidian is built on a web-based technology called Electron—but Voorhees says it’s his favorite writing tool regardless. He and Viticci have even commissioned some bespoke plug-ins for their Macstories workflows.

Obsidian在某些方面与典型的MacStories应用程序恰恰相反——该网站经常突出显示那些专为Apple平台定制的应用程序,而Obsidian则是基于一个名为Electron的网络技术构建的——但Voorhees说,无论如何,它都是他最喜欢的写作工具。他和Viticci甚至为他们的Macstories工作流程定制了一些专属插件。

“No matter what your writing needs are, there’s probably a plug-in to satisfy them,” he says.

“无论你的写作需求是什么,可能都有一个插件可以满足你,”他说。

Staying small保持小型

About a month ago, Ango went on social media to draw some lines in the sand about Obsidian’s future. On X and Mastodon, he declared that Obsidian has no plans to grow beyond a dozen employees and would never raise venture capital.

大约一个月前,Ango在社交媒体上明确了Obsidian的未来规划。他在X和Mastodon上宣布,Obsidian无计划扩大到超过十二名员工,也永远不会筹集风险投资。

Ango is clear-eyed about the limitations of that approach. It means Obsidian can’t develop new features as quickly as other apps, and it can’t chase growth by offering its paid services below cost. But the self-imposed limits, he said, are a way to uphold the company’s values. (Ango has also written an impassioned defense of the computer file, at a time when cloud-based apps are increasingly moving away from the idea.)

安戈对这种方法的局限性有清晰的认识。这意味着黑曜石不能像其他应用那样快速开发新功能,也不能通过低于成本的价格提供付费服务来追求增长。但他说,这些自我设定的限制是维护公司价值的一种方式。(安戈还在一个时期写了一篇对计算机文件的热情辩护,当时基于云的应用越来越多地离开了这个想法。)

“We want to build Obsidian as a team with a flat hierarchy and few meetings,” Ango says via email. “We want everyone to be a contributor, and have a high level of craftsmanship and focus. We want the files our users create with Obsidian to be durable, and not locked into proprietary platforms.”

“我们希望构建一个层级扁平且会议少的Obsidian团队。”Ango通过邮件说。“我们希望每个人都能成为贡献者,拥有高水平的技艺和专注。我们希望用户使用Obsidian创建的文件能够持久,而不是被锁定在专有平台上。”

Keeping the team small and spurning outside investment is Obsidian’s way of avoiding incentives that might lead the company astray.

保持团队规模小且避免外部投资,是Obsidian避免可能使公司偏离轨道的激励的方式。

“We are lucky to be building Obsidian at a time when it is possible to build a complex, multi-platform app with millions of users — while remaining a very small team,” Ango says. “We want to find out how far we can take that experiment.”

“我们很幸运能在这样一个时代建立Obsidian,那时我们可以构建一个复杂的、多平台的应用程序,拥有数百万用户——同时仍然是一个非常小的团队,”Ango说。“我们想要看看我们能把这个实验进行到何种程度。”

Obstacles ahead前方的障碍

Obsidian doesn’t collect usage data, so it doesn’t know exactly how many people are using it. Based on the number of downloads from its GitHub page, Ango estimates that Obsidian has roughly 1 million users. Notion, by comparison, boasted of 20 million users in 2021 (though it hasn’t updated that figure since).

Obsidian并不收集使用数据,因此它并不确切知道有多少人在使用它。根据其GitHub页面的下载次数,Ango估计Obsidian大约有100万用户。相比之下,Notion在2021年宣称有2000万用户(尽管自那时起它并未更新这个数字)。

Even Obsidian’s most dedicated users don’t expect it to take on Notion and other note-taking juggernauts. They see Obsidian as having a different audience with different values.

即使是Obsidian最忠实的用户也不期望它能与Notion和其他笔记巨头竞争。他们认为Obsidian有着不同的受众和不同的价值观。

“The people who are sitting around hacking on the incredibly flexible, but kind of difficult-to-use and not immediately intuitive and beautiful Obsidian, are not the same kind of people making Notion databases,” Konik says.

“那些坐在那里研究极其灵活,但有点难用,不立即直观且美观的Obsidian的人,并不是那些制作Notion数据库的人,”Konik说。

Still, there’s a desire—even within Obsidian—to make the app a bit less intimidating. The software has improved in this regard, most notably by removing Markdown syntax from its main editor (in favor of a “Live Preview” mode) in late 2021, but users are still expected to know Markdown for formatting. Some creature comforts from other modern note-taking (such as Notion’s handy pop-up formatting menu) are absent.

尽管如此,Obsidian内部仍有一种愿望——让这款应用程序显得不那么令人生畏。在这方面,该软件已有所改进,最明显的是在2021年底,它从主编辑器中移除了Markdown语法(改为“实时预览”模式),但用户仍然需要了解Markdown来进行格式化。其他现代记事本(如Notion的便捷弹出格式菜单)的一些舒适功能却缺失了。

That’s one reason Jean-Pierre Cen started building Make.md about a year ago. It’s an ambitious plugin that tries to smooth some of Obsidian’s rough edges—for instance by adding a pop-up formatting menu for selected text—and its Folder Note feature is similar to Notion’s system of branching subpages.

这就是让-皮埃尔·森大约一年前开始构建Make.md的一个原因。这是一个雄心勃勃的插件,试图平滑Obsidian的一些粗糙边缘——例如,通过为选定的文本添加弹出格式菜单——而它的文件夹注释功能与Notion的分支子页面系统相似。

“I just want more people to be able to use Obsidian,” Cen says.

“我只是希望更多的人能够使用Obsidian,”岑说。

Such statements might not seem contentious, but within the Obsidian community there’s a wariness of tools that deviate too much from the core Markdown file structure. Cen calls it “Markdown maximalism,” and says it can sometimes be self-defeating.

这样的声明可能看起来并不引人争议,但在Obsidian社区中,人们对过于偏离核心Markdown文件结构的工具持谨慎态度。岑称之为“Markdown极度主义”,并表示它有时可能会适得其反。

“I don’t want to say gatekeeping, but sometimes it feels like that to people who are coming in,” he says.

“我不想说这是门户把关,但有时对于那些刚刚加入的人来说,确实有这种感觉,”他说。

Still, Nick Milo, who’s somewhat skeptical of ambitious plugins such as Make.md, says he’d like to see Obsidian absorb the functionality of more plug-ins and turn them into core features. And even Obsidian recognizes that its learning curve could be gentler.

尽管如此,对于Make.md等雄心勃勃的插件持有一些怀疑态度的Nick Milo表示,他希望看到Obsidian吸收更多插件的功能,并将它们转化为核心特性。甚至Obsidian也承认,它的学习曲线可以更为平缓。

“Our goal for Obsidian is to continue making the app even more approachable for new users, while retaining an infinite level of depth that you can explore through advanced features and plugins,” Ango says.

“我们对于Obsidian的目标是继续使应用程序对新用户更加友好,同时保留无限的深度,您可以通过高级功能和插件进行探索。”Ango说。

There’s also the question of making money. Obsidian is free for personal use, and while it requests $50 per user, per year for teams of two or more, it has no way of enforcing its licensing rules give that it doesn’t track users. (Individuals can also show support with a $25 one-time contribution, which also opens up access to beta releases.)

还有一个关于赚钱的问题。虽然黑曜石对个人用户是免费的,而且它要求每个用户每年支付50美元给两人或更多的团队,但由于它不追踪用户,所以无法执行其许可规则。 (个人也可以通过一次性贡献25美元来表示支持,这也会开放对测试版本的访问。)

Beyond the software itself, Obsidian offers a couple of paid services, each costing $10 per month or $96 per year: Sync offers end-to-end encrypted vault storage, while Publish lets users put their notes on the web.

除了软件本身,黑曜石还提供了几项付费服务,每项服务每月10美元或每年96美元:同步服务提供端到端加密的保险库存储,而发布服务则让用户将他们的笔记发布到网上。

At the same time, Obsidian allows users to assemble their own alternatives for free or cheap. You can use your own file sync system instead of Obsidian’s, for instance, and a quick search of Obsidian’s plug-in store reveals plenty of options for publishing notes to the web. Even Obsidian’s most passionate users note that it’s not an ecosystem geared toward making money.

同时,黑曜石允许用户自行组装免费或低成本的替代方案。例如,你可以使用自己的文件同步系统,而不是黑曜石的,快速搜索黑曜石的插件商店会揭示出许多发布笔记到网上的选项。即使是黑曜石最热情的用户也注意到,这并不是一个以赚钱为目标的生态系统。

“You can almost always find something for free, because some guy will get pissed off that somebody is charging money for something he views as trivially simple,” Konik says.

“你几乎总能找到免费的东西,因为总有人会对别人为他认为微不足道的简单事物收费而感到愤怒。”Konik说。

But maybe that’s okay. Obsidian’s low overhead and ambivalence about growth allows those money-making limitations to be sustainable, and the idea that Obsidian’s own users can compete on some level with the company’s paid offerings is part of why people love the app. It’s a rejection of how modern software is supposed to work, and it’s slowly gaining momentum.

但也许这没什么。Obsidian的低开销和对增长的漠不关心使得这些赚钱的限制变得可持续,而Obsidian自己的用户能在某种程度上与公司的付费产品竞争,这就是人们喜欢这款应用的部分原因。这是对现代软件应有工作方式的拒绝,而且它正在慢慢获得动力。

“Why would I pay a cloud service to work slower? Just because it looks nice?” Milo says. “There’s a huge silent majority of individuals who have a similar sentiment.”

“我为什么要付费给一个运行速度更慢的云服务?就因为它看起来不错?”米洛说。“有一大批默默无闻的人们,他们的感受与我相似。”

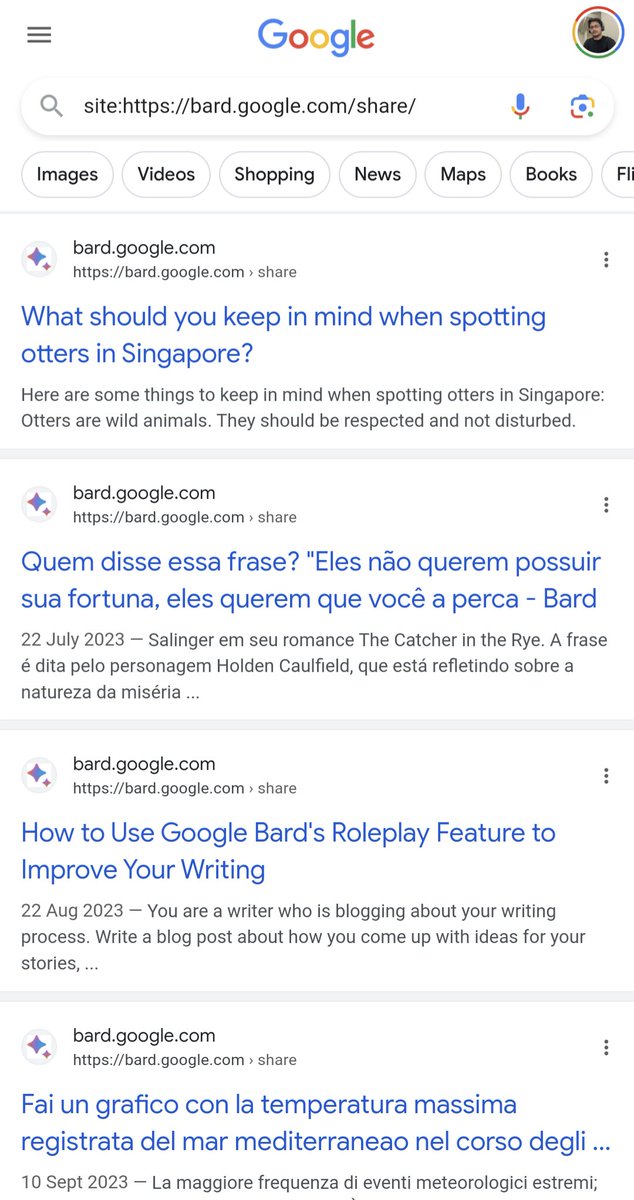

Conversations with the Google chatbot turned up in search results for common queries—an issue the company says was an error.

与Google聊天机器人的对话出现在常见查询的搜索结果中——该公司表示这是一个错误。

[Images: arthobbit/Getty Images; blacklight_trace/Getty Images]

[图片:arthobbit/Getty Images; blacklight_trace/Getty Images]

AI-powered chatbots are designed to be the always-available advisors that will power the next era of productivity. But they have a privacy problem—as evidenced by a recent misstep by Google.

AI驱动的聊天机器人被设计成始终可用的顾问,将推动下一个生产力时代的发展。但是,他们存在隐私问题——正如Google最近的失误所证明的那样。

The search giant, which developed its Bard AI chatbot in response to the arrival of OpenAI’s ChatGPT late last year, has been inadvertently leaking conversations into its search results—an issue that is now being remedied after having been made public.

这家搜索巨头,为应对去年晚些时候OpenAI的ChatGPT的到来而开发了其Bard AI聊天机器人,不经意间将对话泄露到了其搜索结果中——这个问题现在正在被解决,因为它已经被公之于众。

SEO consultant Gagan Ghotra first raised the issue that URLs linking to conversations users had with Bard were showing up in Google’s search index, the database of websites that the search engine crawls in order to provide answers to users’ queries.

Haha 😂 Google started to index share conversation URLs of Bard 😹 don't share any personal info with Bard in conversation, it will get indexed and may be someone will arrive on that conversation from search and see your info 😳

Also Bard's conversation URLs are ranking as snippets for some queries as well 🤣🤣

Ghotra shared a screenshot showing users’ private conversations with Bard asking for tips about how to spot otters in Singapore, and how to use Bard to improve your writing. Clicking on those links would take users to the historical record of a conversation another user had with Bard on the topic. Peter Liu, a research scientist at Google DeepMind, quickly clarified that chat conversations appearing in search results had previously been shared with another user using the Share functionality common in AI chatbots—which allows users to provide links to people of their choosing.

Liu was criticized for what some saw as an attempt to downplay the seriousness of the breach in user confidence in privacy. Critics suggested that users who shared links to their chats were doing so with only a small circle of people they chose, rather than all and sundry on the internet. “It’s a pretty subtle point, but it’s actually really important,” says Simon Willison, the AI critic and creator of Datasette.

“This is fundamentally a privacy feature,” says Willison. “Everything you say to Bard is private by default, but there’s a feature that lets you share that conversation.” Willison suggests that users would expect their conversations only to be shared with whomever they choose. He points to the text used in the user interface for the Share functionality with Bard. “’Let anyone with the link see what you’ve selected’,” he says. “That implies that only people who you send the link to will be able to see the conversation.”

That wording, Willison says, suggests that there is a limit to where the conversation will go. “Your shared link showing up in random searches is a breach of your expectations when you used the share feature,” he says. Willison points out that ChatGPT has a similar Share button on its service. “But ChatGPT sharing, as it should do, includes code in the HTML to block the shared content from being indexed by search engines,” he says. “Google Bard evidently forgot to include that, and as a result Google Search started sweeping up those conversations.”

The issue is compounded by the fact that the inclusion of chat conversations in search results—which Google DeepMind’s Liu seemed to imply was by design, and an example of the Share functionality working normally—is contrary to what has gone before. “This is very different from what Google does with products like Google Docs and Google Drive,” says Margaret Mitchell of AI company Hugging Face, who points out that on those other products, for Enterprise users, share options will warn you about the risks of sharing content with people outside your organization’s domain name.

That inconsistency between what Google has previously done and what it appears to be doing now is confusing for everyday users, she reckons. “For users who have an expectation of consistency, or an assumption of basic privacy aligned with the norms Google has already established in its products, this is creepy and underhanded,” she says. “Whoever approved this is way out of sync with what is already known about privacy at Google. Or intentionally overriding it, which is a pretty intense move for something Google admits is an experiment.”

Mitchell’s initial reaction when shown by Fast Company what had happened was shock. A Google spokesperson declined to comment on the record for this story, but pointed to a tweet from Danny Sullivan, the company’s public liaison for search, who seemingly admitted this was an error. “Bard allows people to share chats, if they choose,” Sullivan wrote. “We also don’t intend for these shared chats to be indexed by Google Search. We’re working on blocking them from being indexed now.”

The issue is such a concerning one because of the way users have adopted AI chatbots as the 21st century confession booth. Recent research shows users are willing to share private identifying information with ChatGPT, while Lilian Weng, a worker on OpenAI’s own AI safety team, this week suggested that users might want to try using her company’s chatbot as an alternative to a therapist. The risk of those conversations becoming public appears not to have been taken into consideration.

Google’s quick action to fix the breach is commendable, says Willison, but highlights a broader issue about the race for AI supremacy that Google, Microsoft, OpenAI, and a clutch of other companies are currently engaged in. “It’s a good illustration of how all three companies are moving at a breakneck speed to compete with each other,” he says, “which makes it more likely that mistakes like this one will slip through to production.”