Stories are bad for your intelligence

Length: • 9 mins

Annotated by Erik

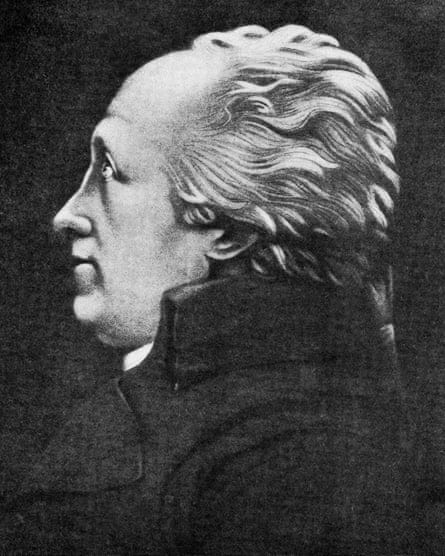

This is Henry Cort. You probably haven’t heard of him unless you’re an Industrial Revolution nerd (I hadn’t until this week). He isn’t as well known as James Watt or Joseph Priestley - he wasn’t one of the Lunar Men - but Cort played a critical part in the creation of the modern world. He invented a method of production which made it much easier and cheaper to turn scrap iron into high-quality iron, ready to build railways, warships, bridges and balconies.

Cort pioneered and combined two innovations. One was an improvement on Peter Onions’s puddling process, which we needn’t dwell on here - really, I just wanted to write out, “Peter Onions’s puddling process”. The other was the use of grooved rollers. Traditional rolling mills used flat rollers to roll hot metal into simple, flat shapes. Cort’s rollers had grooved edges which made for perfectly smooth, welded bars.

The “Cort process”, introduced in the 1780s, led to a quadrupling of Britain’s iron production over the following twenty years, making Britain one of the world’s leading iron producers. Fifty years after his death, the Times called Cort “the father of the iron trade” and today he’s regarded as one of the twenty or so most important innovators of the era.

Now comes a twist in the tale. A lecturer in science and technology at UCL called Jenny Bulstrode has published a paper which argues that what she calls “the myth of Henry Cort” is based on a lie.

In the prestigious journal, History and Technology, Dr Bulstrode argues that Cort stole his innovations from black slaves who had developed them independently in an iron works in Jamaica. Bulstrode traces a complex chain of events by which Cort, who as far as we know never visited Jamaica, ended up claiming credit for a process which was collectively invented by 76 enslaved factory workers (Bulstrode refers to them as “Black metallurgists”).

Bulstrode’s paper centres on a Jamaican ironworks run by an English industrialist called John Reeder. Within a few years of setting up, his foundry became successful and profitable. Reeder’s workforce included slaves trafficked from West Africa and trained by English experts he shipped over. Bulstrode argues that the black workers, drawing on ancient African traditions of ironwork, and from their experience of sugar production (where a kind of grooved roller is used) developed these new methods of their own volition, and that it was this which accounted for the factory’s impressive profits.

So how did Cort find out about it? Well, he ran an ironworks in Portsmouth, which he took over in 1775. Bulstrode notes that in 1781 a man with the surname of Cort arrived in Portsmouth from Jamaica. She describes him as a ‘cousin’ of Henry Cort, although as she notes, that term was often used to mean a distant relative. This second Cort had no connection to Reeder’s mill either, but Bulstrode argues that he must have heard all about the foundry and its innovative process when he was in Jamaica. She says he then met Henry Cort in Portsmouth, and passed on this valuable information.

A few months later, in 1782, Reeder’s factory was razed to the ground under orders from the British government. This was previously thought to have been because the colony was under threat from rival European powers and the British wanted to prevent the foundry from falling into French or Spanish hands. Bulstrode says that the military governor disclosed an ulterior motive: the British wanted to stop the factory from being taken over by black Jamaicans, who might then be empowered to overthrow their colonial rulers (in an interview with a podcast called The Context of White Supremacy, Bulstrode even suggests that Henry Cort instigated the destruction via contacts in the British government). Bulstrode says that components from the destroyed factory were then shipped to Portsmouth, with the implication being that Cort then reverse-engineered the process, and patented the secrets under his own name.

Bulstrode’s paper has made a big splash. It’s been hailed by her academic peers as a major breakthrough, and picked up by big media outlets including the Guardian, the New Scientist, and NPR. If you Google “Henry Cort”, it’s these reports which come up. Wikipedia has already incorporated it into Cort’s biography. Bulstrode’s paper fits the zeitgeist in historical studies - that the economic success of Britain and the West owes much more to the exploitation of black ingenuity and ideas than mainstream historians have hitherto allowed for.

If the story Bulstrode tells sounds incredible, that’s because it is. Right after Bulstrode’s paper made the headlines, Anton Howes, the proprietor of an excellent Substack on the history of innovation, noted the almost total lack of evidence for the paper’s central claims. Last week, he returned to it in a piece sparked by a new paper from Oliver Jelf which examines Bulstrode’s paper in detail and provides the most thorough debunking of it imaginable.

Jelf’s paper is a crisply argued, ruthless demolition job which makes for a gruesomely compelling read (I suggest reading Bulstrode’s paper first). Jelf takes each of Bulstrode’s central claims and finds them to be, not just dubious, but demonstrably false. He draws on his own expertise on the period but often, all he has to do is point us to the very sources Bulstrode cites in order to show that her conclusions are unsupported.

In reality, John Reeder’s foundry used very ordinary (run-of-the-mill?) production processes. No innovations were introduced there, by the workers or anyone else. Its profitability needs no extraordinary explanation; Reeder had the only foundry on the island and supplied the Royal Navy. The elaborate chain of events by which Cort is supposed to have found out about these non-existent innovations simply didn’t happen. Cort’s cousin did not go to Portsmouth, but to Lancaster. Henry Cort lived in complete and blissful ignorance of John Reeder’s factory. The factory was destroyed because of the foreign invasion threat and only because of that; at no point did the military governor or anyone else suggest otherwise. No components from the foundry, which was thoroughly destroyed, were shipped to Portsmouth or anywhere else. I could go on but, simply put, none of the assertions Bulstrode makes in her paper stand up to even cursory scrutiny.

Bulstrode hasn’t yet responded to Jelf or Howes in public, but it’s hard to see how her paper can be creditably defended. I’m left wondering two things: one, how she arrived at her narrative at all, and two, how on earth it survived the review process.

On the first, I suspect Bulstrode fell under the spell of story. Her paper has the feel of a messy and flawed first draft of a historical novel. It begins in Lisbon in the fifteenth century (even here, her assertions seem to be mistaken) before skipping to eighteenth century Jamaica, West Africa, and Portsmouth, weaving a web of vague and tenuous connections as it goes. It is clogged with deadening and risibly anachronistic jargon (“sugar and iron shared much overlapping conceptual space”). Most uncomfortably, there is a strain of quasi-Orientalism to its depiction of the black metalworkers, who are presented as magical figures: exceptionally skilled “metallurgists”, conceptual innovators, custodians of ancient and mystical wisdom, noble freedom-fighters. But it is full of nuggets which fire the imagination; names of forgotten people; dim outlines of dramatic events.

I doubt that Bulstrode set out to deceive. My guess is that she came across a few suggestive fragments in her reading (the ‘cousin’ of Cort travelling from Jamaica to England) and wanted so badly to make them into a story which fitted her ideologically determined prior - that the British stole ideas from those they enslaved - that she got carried away, fabricating causes and effects where none existed.

It’s one thing for a young and passionate academic to make mistakes; it’s quite another for a series of experienced academics to let her make them. The paper had two anonymous peer-reviewers (Bulstrode thanks other historians in an endnote, though they may not have read the paper). Even to an ignorant reader like me, the paper just smells funny - it has the aroma of the fantastical. How on earth did these experts read it without becoming suspicious? Why didn’t they double-check its remarkable claims?

My guess is that they were also seduced by story. It’s not just that Bulstrode’s storytelling mind went into overdrive, it’s that the master-narrative into which her paper fits now exerts such a grip over some historians that they will blind themselves to anything which undermines it. According to this narrative, Britain’s Industrial Revolution was not the product of ingenuity or the free exchange of ideas, but of thievery and exploitation. The British stole, not just the labour and materials of black countries, but their ideas too. If your paper fits that narrative, it’s more likely to get published, even if it has holes in it; even if it is nothing but holes. The discipline, or a sub-set of it, has become helplessly in thrall to one of the archetypal narrative forms: Good vs Evil. Naturally, the academics are on the side of the Good.

Anton Howes argues that, like the field of psychology has done in recent years, history must confront its own “replication crisis”. Errors are allowed to survive and spread throughout the corpus for decades. His solution is widen access to archival sources to make it easier for peer-reviewers to check claims. But if peer-reviewers aren’t motivated to be sceptical, this may not help much. I draw a different moral, which is that historians need to train, or retrain, themselves, to be suspicious of story and narrative.

Historians have an increasingly strong incentive to tell dramatic stories which gain attention and make ‘impact’. But anyone in the business of reporting on reality - scholars, scientists, journalists - ought to be suspicious of narrative, even if they use it. So should those of us who consume these reports. Just because information is conveyed in narrative form doesn’t make it false, but it does mean that it’s going to seem more true than it is.

Stories are reality filters. By definition, they leave out information - all the messy stuff that doesn’t fit - and draw attention to what the storyteller wants us to notice. In that sense they are like ideologies: both are methods of rolling and shaping the hot metal of reality into smooth ready-made shapes. Stories don’t accommodate randomness or structural forces very well; they rely on chains of causation and on individual motive. Covid-19 can’t be an accident and we needn’t bother ourselves too much with biology; it is a plot perpetrated by evil people. Bulstrode’s paper has the flavour of a conspiracy theory. Conspiracy theories aren’t theories; they’re stories.

Stories act like an anaesthetic on our sceptical, questioning faculties. It can be valuable and pleasurable to subdue that part of our brain, and immerse ourselves in an imaginary world; I love reading stories, including non-fictional ones. But if you come across a history book, or a scientific study, or a news report, which tells a great story, or which slots neatly into a master-narrative in which you already believe, you should be more sceptical of its truth-value, not less. Narrative can give an illusion of solidity. When the expert narrative about the world changes, as with China (see below), we shouldn’t just conclude that the old narrative was false, but that all such narratives are unreliable.

In Metahistory, his classic work of historiography, Hayden White argued that historians are always drawing on literary forms, like tragedy or comedy, whether they realise it or not. That isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but if you’re a historian you have to be aware of it; otherwise the story writes you rather than the other way around. Moralising narratives are particularly potent. Historians of the British empire are currently substituting one simplistic narrative for another in popular books.

In a sense, Cort was an easy target for Bulstrode because he didn’t have a story of his own; he was narratively undefended. If Cort is less well known than Watt or Priestley that’s because neither his life or work have been moulded into a story; other than his innovations, Cort left barely a trace behind. He wasn’t a flamboyant character, but one of those diligent, determined, curious tinkerers on whom the Industrial Revolution was built (in my book CURIOUS I call them “thinkerers”). His innovations probably emerged from years of slow, sooty experimentation, without any eureka moments or dramatic breakthroughs.

Stories are indispensable, nourishing and delightful. They are also attacks on the rational immune system. TED Talks are, famously, all about stories, but when the economist Tyler Cowen did one he used it, rather subversively, to warn against “story bias”. Cowen argues that any time someone believes in a story they are effectively subtracting ten points from their IQ (by which he means, broadly speaking, their analytical intelligence). That’s a deal we will often take willingly, since stories can bring pleasure and meaning to our lives and deepen our understanding of the world. But let’s be clear about what the deal is.

The Ruffian depends on its paid subscribers; if you’re a free subscriber, please consider an upgrade. Paid subs get all the best stories.

After the jump, what I’ve been reading; some extremely juicy links and stories: a new take on Barbie (inexhaustible subject), a defence of Oppenheimer, my favourite Wikipedia page, Jimmy Stewart’s theory of film, an investigation of Napoleon’s luck, and more...