Dollar General: Rural America's Retailer

Length: • 35 mins

Annotated by Chris Pavese

You can listen to the Deep Dive here

I am not sure how many of my readers ever set their foot in a Dollar Store in America, but there are more Dollar Stores in the US than Starbucks, Walmart, and McDonald's combined. Dollar General is the leading Dollar Store brand in the US with almost 20,000 locations across 47 states in the US.

The origin of Dollar General was reminisced by Cal Turner Jr. ,who was CEO of Dollar General from 1965 to 2003, in his book “My Father's Business: The Small-Town Values That Built Dollar General into a Billion-Dollar Company”:

J.L. Turner and Son, as it was called then (James Luther Turner was my grandfather), had 36 retail stores, generally partnerships with local merchants, in small Kentucky and Tennessee towns. The business, headquartered in Scottsville, Kentucky, was grossing about $2 million annually, and my dad was always looking for ways to grow. He was a keen observer of both his customers and the competition, and he became intrigued by the “Dollar Days” sales put on by the big department stores in Nashville and Louisville. Once a month, they would take out huge full-color newspaper ads and sell merchandise with $1 as the single price point. My dad knew what those ads cost, and he understood that if they were spending that kind of money, they were selling a lot of goods. Customers obviously loved that $1 price point. Somehow, it made real value seem even more obvious.

“Why couldn’t we simplify all of our operations,” he thought, “by opening a store with only one price—a dollar?” Every day would be Dollar Day. In that flash of insight, he saw any number of benefits. Customers could keep track of what they were spending more easily, and checkout would be simplified.

While Dollar Stores have become quite prevalent in the US, the original idea of a Dollar Store has become somewhat obsolete. Dollar General stopped selling items only for a dollar decades ago; its closest competitor Dollar Tree held onto the original Dollar Store philosophy for far longer before giving up just a couple of years ago. Therefore, today the Dollar Stores mostly evoke a sense of “value” even though they have moved away from the original idea of Dollar Stores.

After Turner family successfully ran the Dollar General business from 1955 to 2003, David Perdue was the first outside CEO and led the company for four years before KKR acquired Dollar General in 2007. When Dollar General first came to IPO in 1968, one share of Dollar General was worth $16.5 which would be $6,555 in 2007, implying ~16.6% CAGR over 39 years.

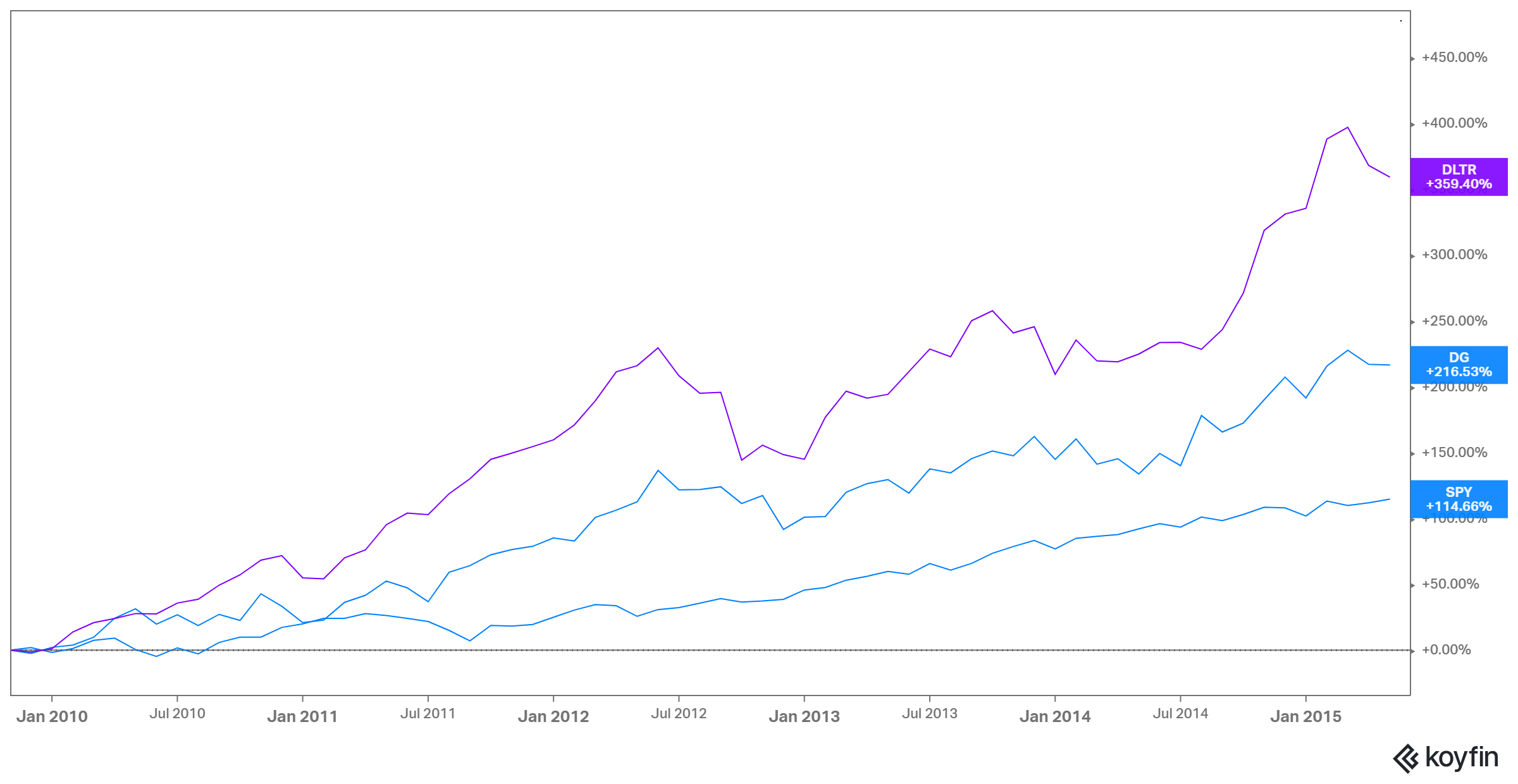

KKR’s buyout of Dollar General was incredibly well-timed. During the Global Financial Crisis while S&P 500 Index went down by 38% in 2008, Dollar Tree was the best stock in the S&P 500 Index with +64% gain in the year. As the recession forced many people to trade down, Dollar Stores proved to be quite countercyclical.

KKR bought Dollar General for $7.2 Bn, but put down only $2.8 Bn equity and the rest was financed via debt. When Dollar General became public again in 2009, its Enterprise Value was ~$12 Bn and the equity was worth ~$8 Bn. Dollar General was a home run for KKR.

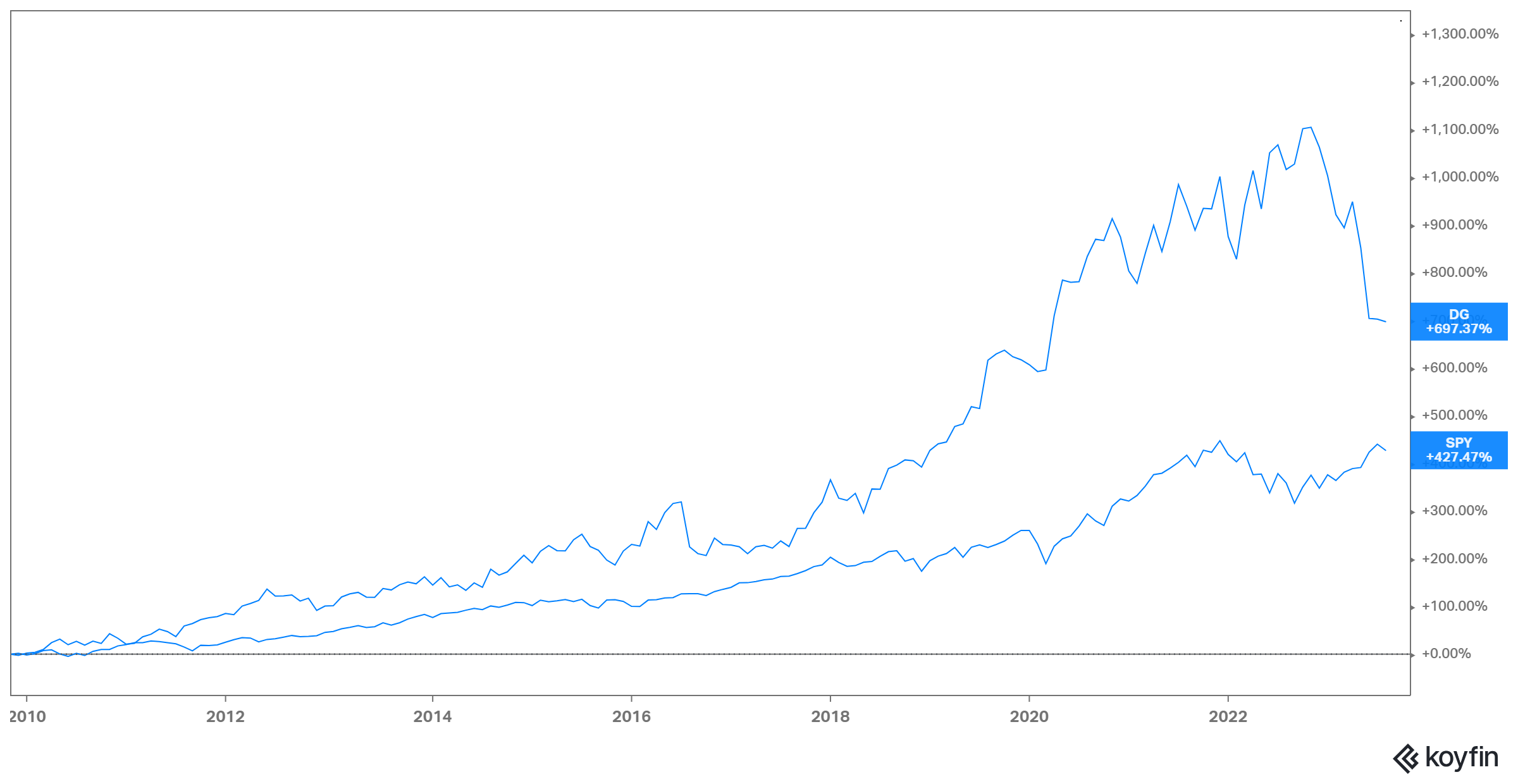

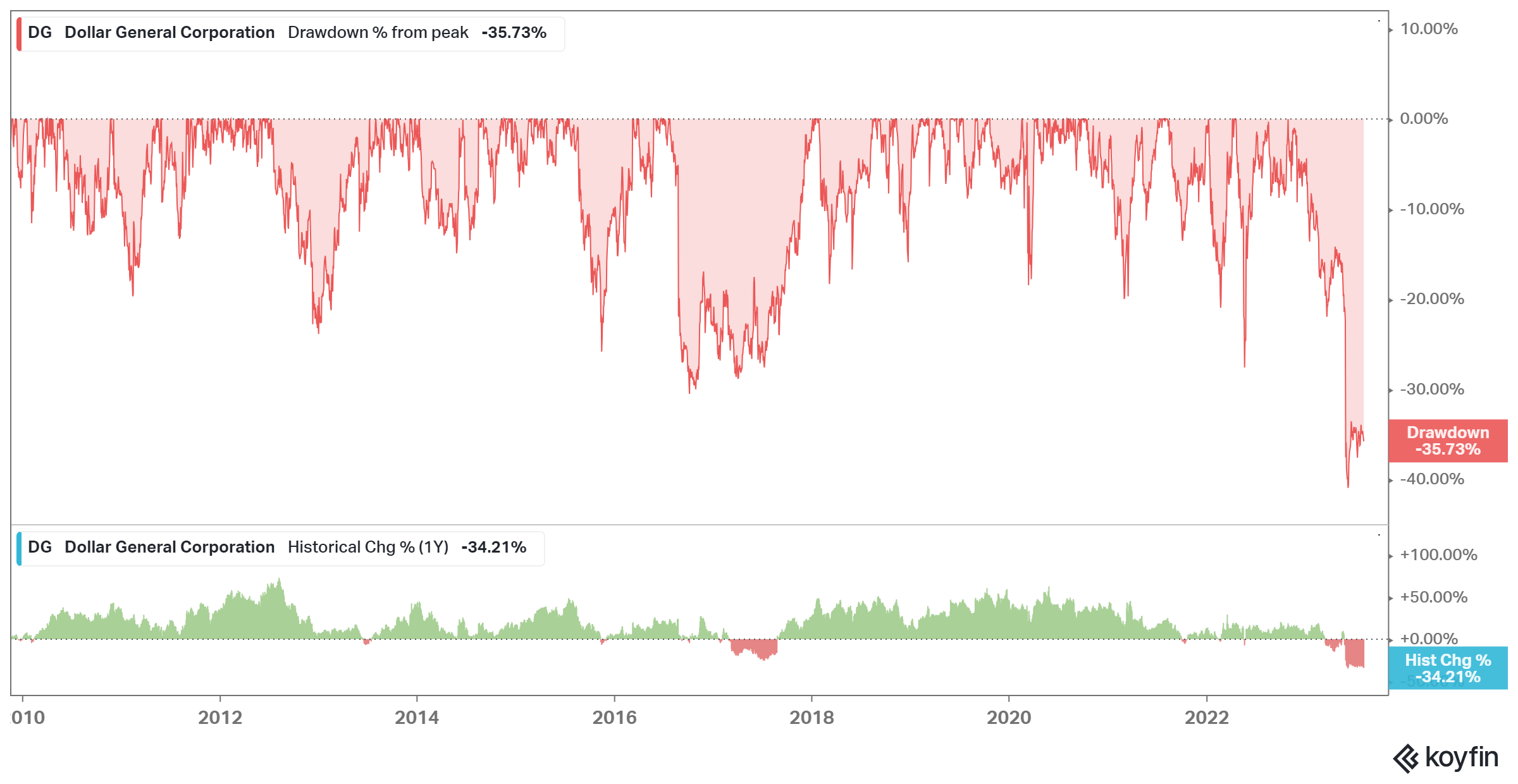

Dollar General handily beat the S&P 500 index even after it recently experienced its largest ever drawdown since becoming public again. The question is, of course, whether the current drawdown is a great opportunity for investors.

Here’s the outline for this month’s Deep Dive:

Section 1 Dollar General’s Business: I start the business overview with three key questions: a) who shops at Dollar General, b) why do they shop there?, and c) what do they buy in these stores? Then I discuss the unit economics of a Dollar General store.

Section 2 Competitive Dynamics and Near-term Challenges: In this section, I explored the rivalry between Dollar General, Family Dollar, and Walmart and some other near-term challenges that have been plaguing Dollar General.

Section 3 Long-term Debates: Beyond the near-term challenges, I mentioned some longer term concerns and what I think about them.

Section 4 Capital Allocation and Management Incentives: I explained on this section why I am a fan of neither Dollar General’s capital allocation nor their management incentives.

Section 5 Model Assumptions and Valuation: Model/implied expectations are analyzed here.

Section 6 Final Words: Concluding remarks on Dollar General, and disclosure/discussion of my overall portfolio.

To discuss Dollar General’s business, I want to talk about a) who shops at Dollar General, b) why do they shop there?, and c) what do they buy in these stores?

Who

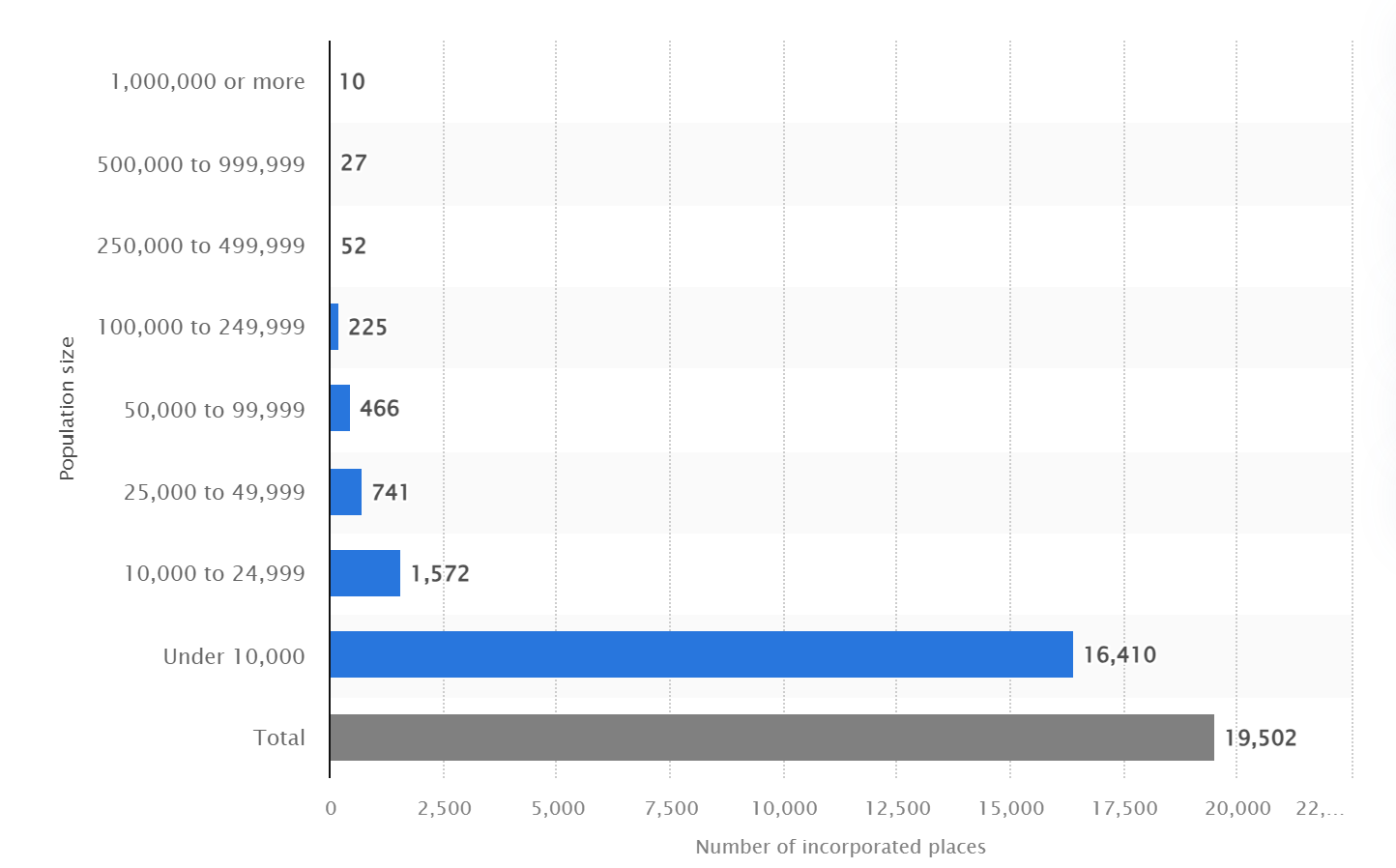

United States is a country of small towns. Nearly half of all municipalities in the US have fewer than 1,000 people living in them. The economics of serving such small towns can be quite challenging for big box retailers such as Walmart, Target, or Costco. Dollar General fully capitalized on this gaping hole and even after launching the concept of “Dollar Stores” in 1955, they continue to open roughly three stores everyday in the US. Today, there is likely one Dollar General store within 5 miles of 75% of the US population.

Dollar General mentions 80% of their stores are located in towns of 20,000 or fewer people (~30% of the US population likely lives in such towns). Interestingly, they mentioned this number to be ~70% in 2015-16, then 75% in 2017-2021, and 80% in their latest 10-K which implies Dollar General had deepened its focus on small towns even more over time.

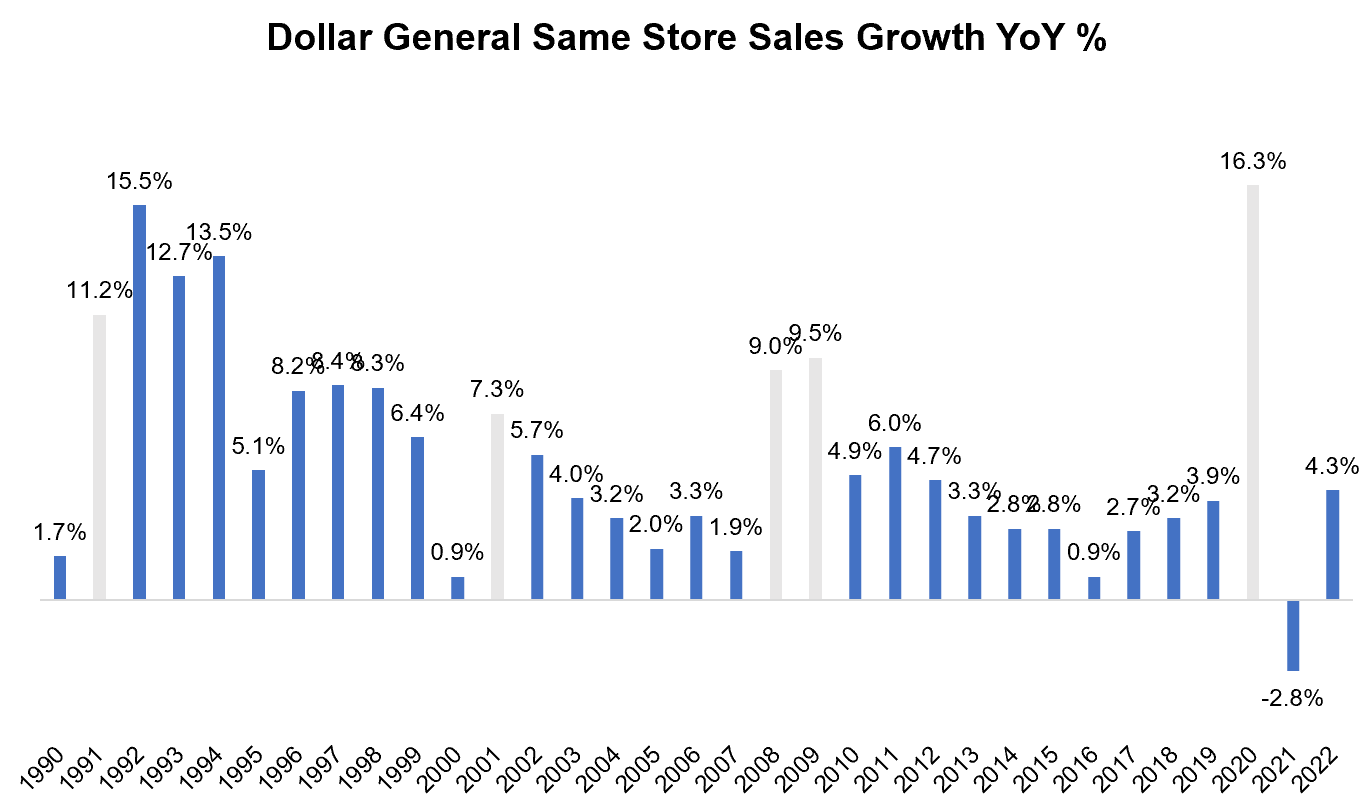

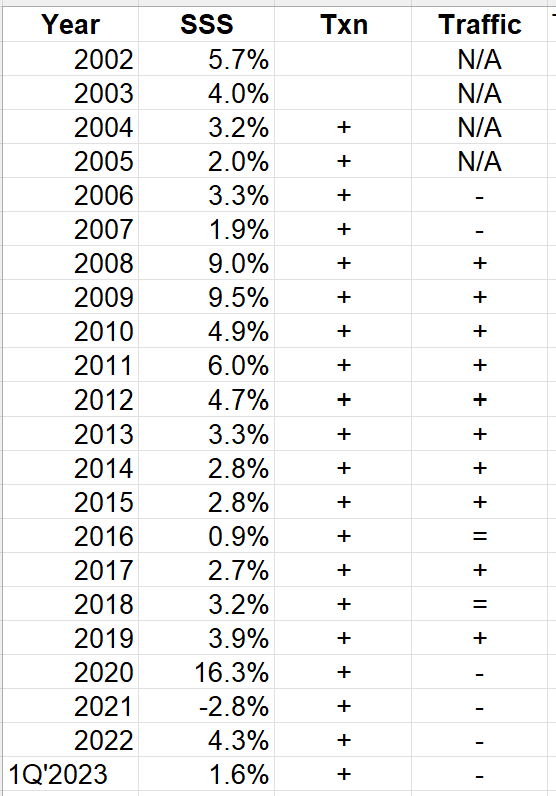

The typical Dollar Store customers make less than $50k a year which is ~36% of the US households. During economic recessions, Dollar Stores tend to benefit from trade downs by middle class consumers trying to curb down their expenses. In the last four recessions in the US, Dollar General’s Same Store Sales (SSS) always enjoyed a considerable boost (recession years shown in grey color). Therefore, there is an element of countercyclicality to Dollar General’s key operating trends.

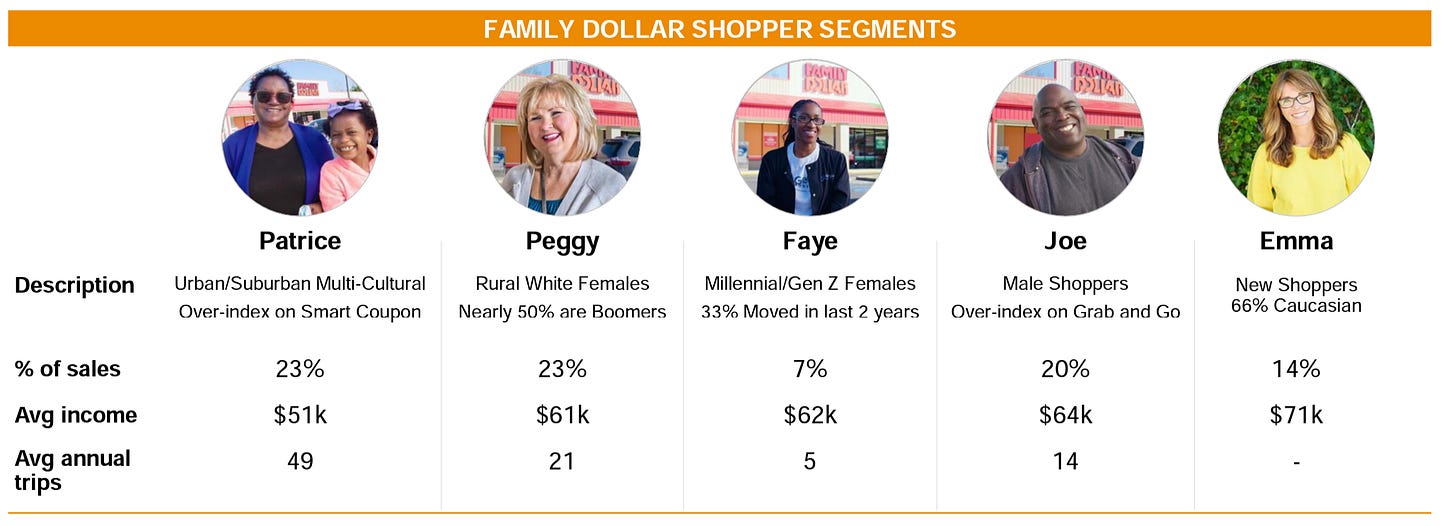

The average basket per trip for these customers is likely between $12-15. The core customer base for Dollar General makes multiple trips per week. On the recent Investor Day presentation, Dollar Tree shared typical customer characteristics of Family Dollar, which is the closest comp for Dollar General. Please note that Family Dollar geographically over-indexes on relatively more urban areas compared to Dollar General; therefore, Dollar General’s typical customer base likely mostly consists of “Patrice” and/or “Peggy”, as shown below.

Why

Why so many Americans shop at Dollar Stores is perhaps already evident to you: convenience. In many cases, Dollar General stores may be the only retailer in town and if you want to go to the nearest Walmart, you may have to drive 10 miles (or more). Not only people can be generally reluctant to drive such miles, price of gas itself can drive consumer behavior. Majority of Dollar General customers are low-income people, so they can be prone to live hand to mouth. As a result, they often need to make multiple trips in a week to replenish their basic needs. The “convenience” value proposition is compelling and likely quite durable.

What is perhaps less compelling is the “value” part of the value proposition for consumers. While Dollar Store items may seem like a bargain at first glance, on a per unit basis it can be often not a great deal for customers. Most of their suppliers provide “cheater” sizes exclusively to Dollar Stores. A chocolate could appear to be cheaper at a Dollar store but could also weigh a few ounces less to make the per unit math less favorable for the customers. In some sense, this is a competitive advantage for Dollar Stores against independent stores in the local towns since those local, independent stores cannot source such exclusive products for their customers.

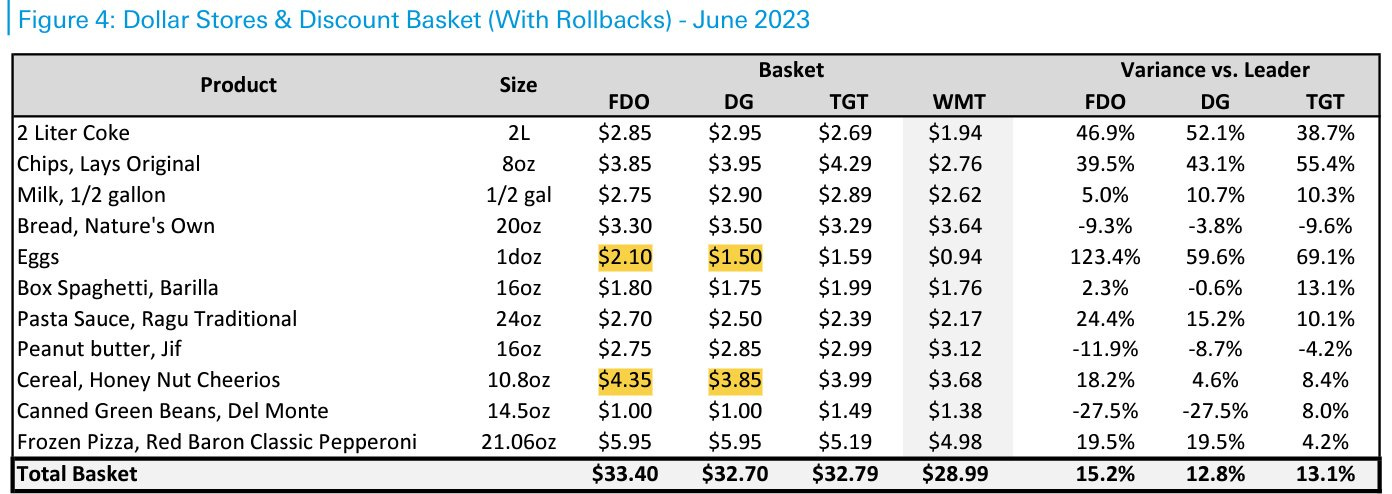

However, even for like-for-like (LFL) products, Dollar Stores often fare poorly against big box retailers such as Walmart. For example, I came across the following table on Twitter (h/t private account) which compared like-for-like (lfl) a basket of products from Dollar General, Target, and Walmart. While the basket costs $33.4 and $32.7 at Family Dollar and Dollar General respectively, it cost only $28.99 at Walmart.

Overall, convenience is the key value proposition for dollar stores and they mostly play with prices to respond to competitive dynamics which I will discuss more in Section 2.

What

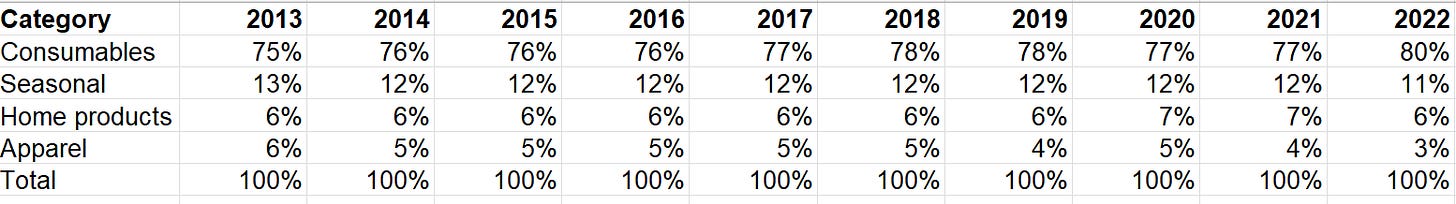

What customers buy at Dollar General can be categorized in four broad categories: Consumables (which I will elaborate more shortly), Seasonal items (holiday items, toys etc.), Home Products (kitchen supplies, candles etc.), and Apparel.

80% of the sales comes from consumables segment. Given consumables is a relatively lower margin segment, Dollar General would certainly prefer to sell the other higher margin segments. In 2018, Dollar General launched Non-Consumables Initiative (NCI) to drive sales in more higher margin products such as housewares and party accessories. Then in 2020, Dollar General introduced another initiative called “pOpshelf”, which built on the lessons learned from NCI and primarily focused on categories such as seasonal and home décor, health and beauty, home cleaning supplies, party/entertainment goods etc. There are both standalone pOpshelf locations as well as store-within-a-store concept within existing Dollar General stores. Management mentioned pOpshelf’s gross margins are 800 bps higher than traditional store.

In 2022, standalone pOpshelf locations was 140 (vs 55 in 2021). Dollar General thinks they can launch 1,000 standalone pOpshelf locations by 2025.

But despite such strategic initiatives, over the last 5-10 years sales contribution from consumables increased from 75% in 2013 to 80% in 2022.

Given supermajority of sales comes from consumables segment, let’s talk about consumables in a bit more detail.

Consumables segment consists of paper and cleaning products, packaged food, perishables, snacks, health and beauty, pet, and tobacco products. Perishable items is more of a recent drive for Dollar General with their launch of “DG Fresh” in 2019. Perishable includes milk, eggs, bread, refrigerated and frozen food, beer, wine and produce etc. Not every store has all these perishable items yet; for example, fresh produce is expected to be available in ~5k stores by the end of 2023 or ~25% of total store base. Dollar General pursued self-distribution model and cut out the middleman for their “DG Fresh” project which may potentially increase margins but also can increase logistics complexities. Dollar General spent $271 Mn, $268 Mn, and $443 Mn on distribution and transportation-related capital expenditure in 2020, 2021, and 2022 respectively. As a result, Dollar General doubled their size of private tractor fleet in 2022 to ~1,600 tractors (and expects to have 2,000 by 2023).

A somewhat skeptical take for their DG Fresh initiative could be that Dollar General may be trying to get ahead of onerous local regulations (even a couple of shareholders I spoke with had sympathy with this take). I will elaborate on this point in Section 3.

Unit Economics

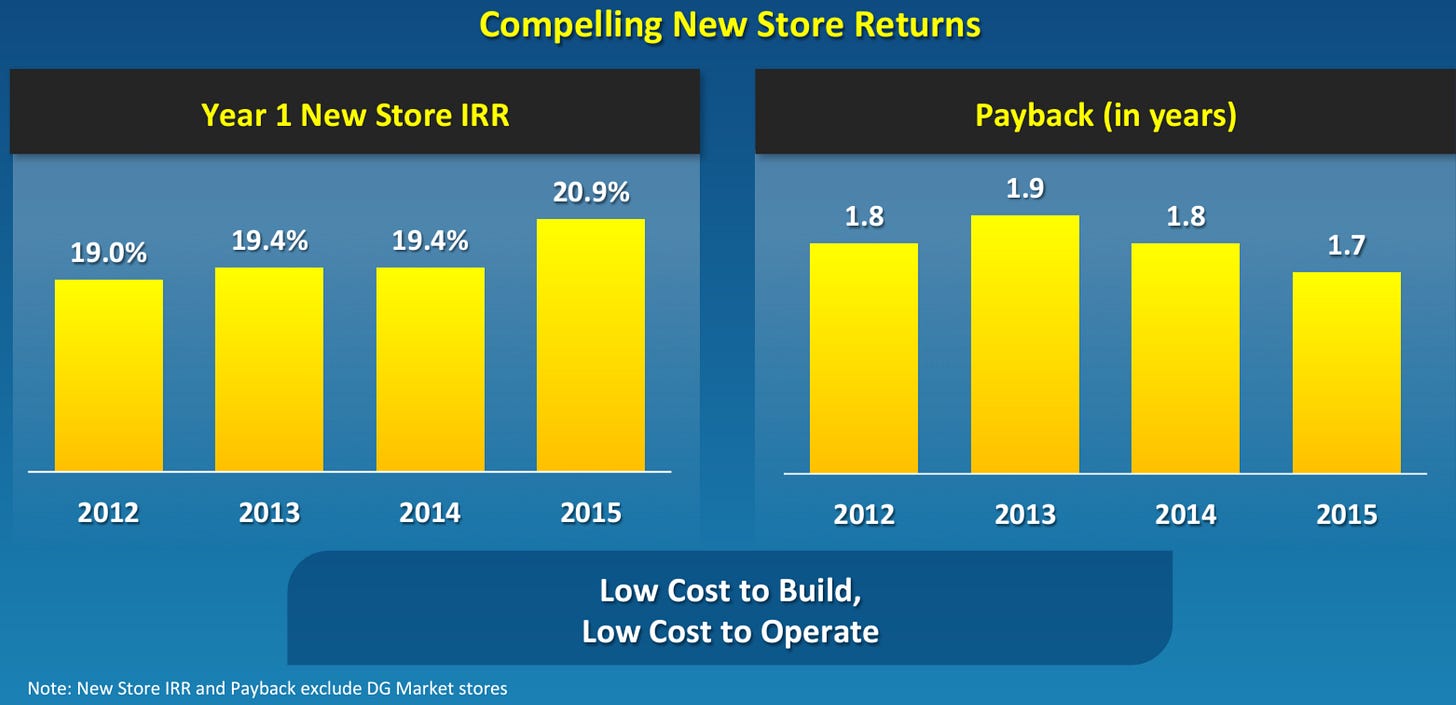

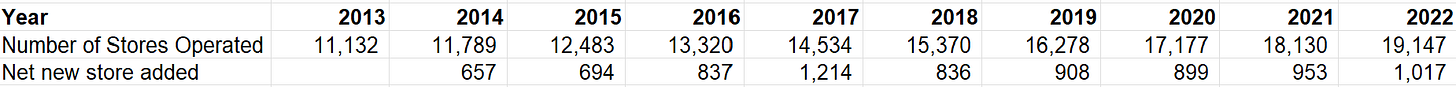

During 2016 Investor Day presentation, Dollar General outlined the unit economics for incremental store. A new store required $250-255k during 2012-15 period and average year 1 sales hovered around 80-85% of Same Store Sales (SSS) base. The new stores typically turn cash flow positive in year 1 and the payback period was consistently less than two years. IRR for the new stores was ~20%. In the last five years, Dollar General opened 4,613 net new stores.

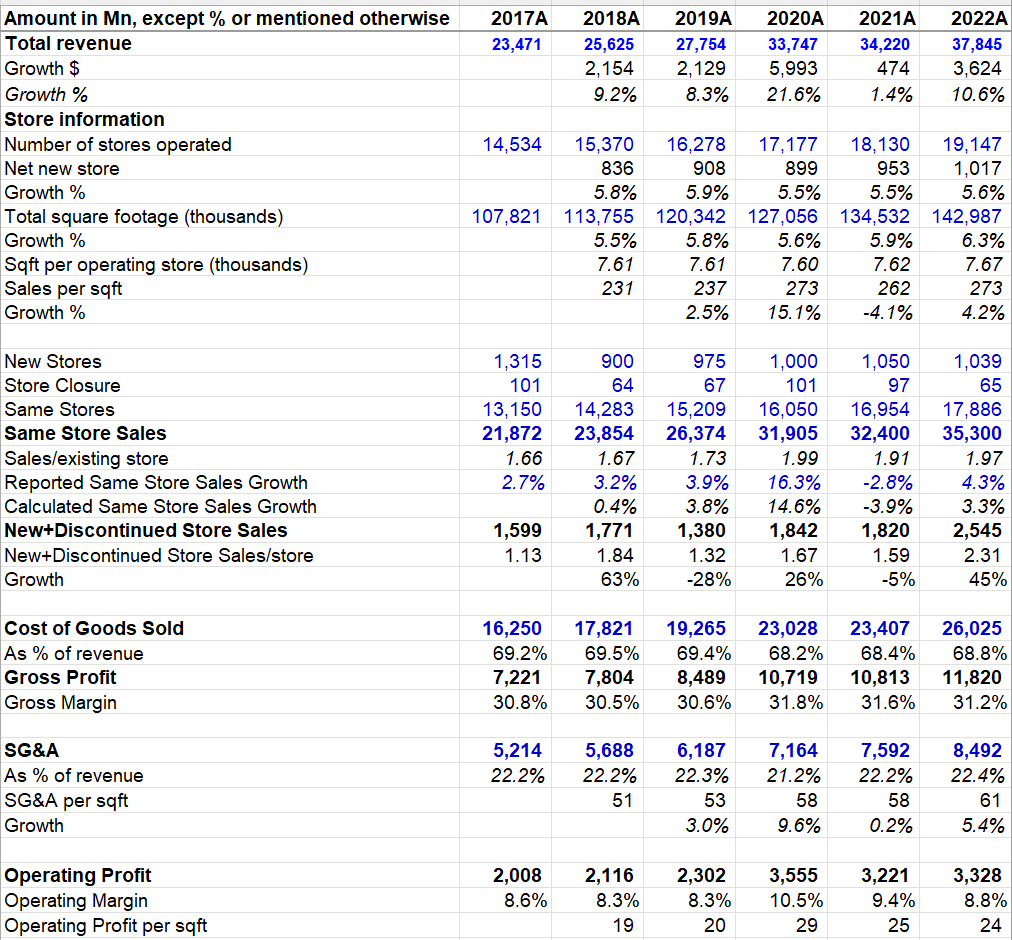

Dollar General’s Sales per sqft increased from $231 in 2018 to $273 in 2022. Given average store size of 7.67k sqft, an average store generated almost $2 Mn in 2022. Dollar General typically had ~11-12k SKUs in their stores with inventory turnover of ~4-5x per year which is similar to Dollar Tree but approximately half of Walmart’s ~8-9x inventory turnover.

Dollar General’s gross margin hovers around 30-31% which is noticeably higher than Family Dollar (the nearest comp) and Walmart both of which post ~24-25% gross margin.

Dollar General has a low operating cost model. Their stores are typically run by one store manager, 1/2 assistant store managers, and 3/4 sales associates. During non-peak hours, in many cases these stores are often run by just the store manager and another assistant store manager (when I visited my local Dollar General store on a Wednesday afternoon, I noticed just two employees). Only the store manager and assistant manager(s) are full-time employees and the rest of the employees are considered part-time employees with max 30 hours per week per person. Operating profit per store for Dollar General increased from $138k in 2017 to $174k in 2022. Operating margin for the company was ~8-10% in 2017-2022 period. In contrast, Family Dollar and Walmart posted ~1-2% and ~4-5% operating margin respectively in the last three years.

Brick and mortar retailing is generally a simple business to understand, but that doesn’t make the business itself easy. Let’s delve into the competitive dynamics and some other near-term challenges Dollar General is facing.

Let’s start with something that perhaps should concern most Dollar General shareholders. The traffic to Dollar General stores is down for the last three consecutive years.

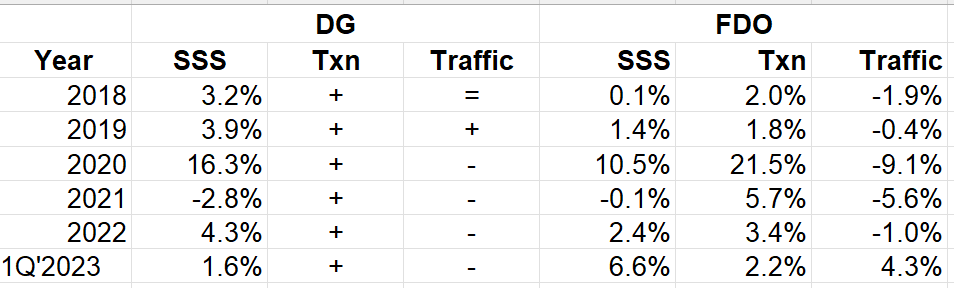

Same Store Sales (SSS) can be disaggregated by two drivers: traffic to the store and transaction amount per customer trip. Dollar General started mentioning about the drivers of SSS in 2004. Ever year since 2004, transaction amount per trip increased which was largely driven by general inflation and selling higher value SKUs. Dollar General started mentioning about store traffic (just up or down, no concrete data point) in 2006. Their store traffic declined in 2006-07 and then increased every year from 2007 to 2015. Since 2015, store traffic trends has been a bit erratic: flat in 2016 and 2018, but up in 2017 and 2019. It is quite understandable that Dollar General experienced decline in traffic during Covid affected 2020. Most customers predictably made fewer trips to the stores but did purchases in bulk during the pandemic. What was perhaps more surprising is continued decline in traffic in 2021 and 2022. Why is traffic declining?

One reason for decline in traffic is the potential cannibalization of sales from newly opened stores. Over the last decade, number of operating stores almost doubled for Dollar General. During 2016 Investor Day, Dollar General mentioned the US market can accommodate ~25k stores. With introduction of initiatives such as pOpshelf in 2020, they later increased the “terminal” number of stores in the US to be ~30k which implies almost another ~10k stores to be opened going forward. If declining traffic is any indication, it is possible that such expansion may lead to some cannibalization of sales from existing stores. If that’s somewhat true, IRR for new stores likely has come down and may fall further. But given ~20% IRR in 2015, even with some downward pressure on IRR, it still is likely quite healthy and may remain so in the future before IRR converging to their cost of capital.

While some cannibalization may not cause insomnia for Dollar General (DG) shareholders, a much bigger concern would be if they lost traffic or market share to competitors. Unlike DG, Dollar Tree discloses Family Dollar’s (FDO) traffic data points. FDO experienced traffic decline in each of the last five years. While DG opened 2,869 net new stores in the last three years, FDO opened only 423 stores during the same time i.e. ~15% of net new stores opened by DG. Because of the wide divergence of store opening cadence, FDO’s store base as % of DG’s store network came down from 63% in 2015 to 43% in 2022. FDO’s ability to effectively compete against DG has waned over time, but there is an ironic history between these two companies.

While Dollar Tree (DLTR) held onto its true “Dollar Store” (everything for $1) promise until recently and hence wasn’t really considered a true substitute for DG where supermajority of products are sold for >$1, FDO was more of a head-to-head competition for DG. DLTR actually acquired FDO back in 2015 for $8.5 Bn ($9.5 Bn including debt) after a bidding war with DG. Despite DG’s higher offer, FDO’s shareholders decided to sell the company to DLTR because of antitrust concerns (for the curious readers, Fortune published a fascinating article on the whole drama).

However, given the bidding war and how things have turned out since 2015, DLTR shareholders perhaps consider FDO acquisition more of a “winner’s curse” at this point. Four years after the acquisition, DLTR had to record $2.7 Bn impairment charge for the FDO acquisition. While it can be tempting to infer DLTR didn’t do a good job with FDO’s stores and may have underestimated the operational challenges of running two separate brands catering to different needs of customers, the recent DLTR investor day presentation also underscored how much underinvestment in IT and general store infrastructure were perpetuated for years at FDO. Even if DG was able to acquire FDO, the chances are perhaps quite high that they too would have a really difficult time in integrating FDO. Given that context, DG shareholders may have been quite lucky to lose the bidding war against DLTR for FDO.

But things may be turning a little in terms of the competitive dynamics between DG and FDO. After five years of declining traffic at FDO, FDO reported 4.3% traffic growth in 1Q’23 whereas DG continued to report traffic decline even in 1Q’23. Thanks to the traffic growth, FDO posted 6.6% SSS vs DG’s only 1.6% in 1Q’23. But it’s only a quarter; is there a reason to think such divergent performance can be persistent?

One reason to think FDO may be finally onto something is the recent management changes at DLTR/FDO. In January 2023, Rick Dreiling, former CEO of Dollar General from 2008-2015, joined Dollar Tree as their new CEO. Just as Paul Hilal convinced the legendary CEO Hunter Harrison to join Canadian Pacific, he did the same with Dreiling to right the ship at DLTR. I do want to note that Dreiling is nowhere nearly as legendary as Hunter Harrison and in fact, during his CEO tenure at DG, DG materially underperformed DLTR. DLTR’s era of waywardness largely began following FDO acquisition which DG took full advantage of over the last decade. Nonetheless, Dreiling certainly understands discount retailing industry intimately and it is interesting to observe FDO’s SSS comp materially improved (vs DG) almost immediately after the leadership change.

Alex Morris has been following discount retailing industry closely for a while and his work has been helpful for me to get up to speed on some of these competitive dynamics in this industry. He outlined how persistent FDO’s issues have been:

The long-term answer for Family Dollar is to run clean and well-stocked stores with competitively priced products (primarily consumables). Despite multiple attempts at remedying the problem over the past eight years (since the acquisition closed in 2015), success has proved elusive; as Dreiling noted in his introduction at Investor Day, “I think Family Dollar is the victim of short-term solutions.”

Alex mentioned a quote by Dreiling from the recent DLTR investor day to explain why management is optimistic that the dog days of FDO may be behind them:

“I don't know if we all remember when I was trying to buy Family Dollar [when he was CEO at Dollar General]; it's interesting, I'm now getting paid to fix something that I said would never work. You go back to 2008, all three of us [DG, Family Dollar, and Dollar Tree] were basically in the same spot... I'm not saying anything bad about anybody, but we [the DG team] knew the reason why we were doing things, and I think Family Dollar was copying us, not understanding what we were doing. I’ll give you all a perfect example. I remember when we made the decision in 2008 to raise the shelf profile to 78 inches. We make that decision, and it took us four years to do it. It took four years because there was absolutely no need to raise the shelf profile unless you had new product to put in it... We went in and redid all the category work, and it took us four years. I remember it like it was yesterday, Family Dollar announces they're raising the shelf profile in their stores. They raised it all the way across, and all they did was spread out what they already had - so what? You just got more inventory. There are repeated, repeated examples of that sort of thing... I think Family Dollar is fixable. I don’t think there's anything that can't be conquered. Now, maybe we're going to have to be a little more persistent than in the past... I’m excited about it, and I believe we've got the right team... In all honesty, the steps we're taking are no different than what I've done in the past [at DG]. The difference is when we did it last time, we were private for two years. A lot of the bumpiness or the grinding, nobody saw, right? We're doing it now in front of everybody...”

Retail businesses can be deceptively simple and intellectually, it can be quite tempting to think none of the problems are unfixable. Yet, Buffett in his 1995 shareholder letter reminded everyone what an unforgiving industry retail can be:

“Retailing is a tough business... I have watched a large number of retailers enjoy terrific growth and superb returns on equity for a period, and then suddenly nosedive, often all the way into bankruptcy... In part, this is because a retailer must stay smart, day after day. Your competitor is always copying and then topping whatever you do. Shoppers are meanwhile beckoned in every conceivable way to try a stream of new merchants. In retailing, to coast is to fail... Buying a retailer without good management is like buying the Eiffel Tower without an elevator.”

Is DG coasting a little bit? There are indeed some indications of that. DG has been recently dealing with some labor issues. As mentioned earlier, apart from manager and assistant manager, everyone working at DG stores are part-time employees who are allocated max 30 hours/week. During my due diligence process, I read a few expert network calls by Tegus and based on these calls, it appears to me that management may have been overly cost conscious to the extent it hurt service levels at the stores. While DG has expanded its offerings by launching NCI, DG Fresh etc, it hasn’t quite kept up in increasing labor hours to maintain service level at the stores. Wells Fargo recently published some analysis on DG’s labor issues and they think that while management is indicating to add 10 hour extra labor hours per store, there may be another 30 hours extra labor hours required in the future. Moreover, Wells Fargo analysts indicated DG pays one of the lowest hourly wages in all of retail which made things challenging for them to attract and retain talent. As a result, while management indicated to invest $100 mn in DG’s existing stores in 2023, these investments may continue well beyond 2023. One of my concerns from reading some Tegus transcripts is management may be targeting certain earnings numbers to hit and adding/subtracting labor hours in a way to meet/exceed those numbers which can often work in the short-term but such underinvestment will catch up with you over the long term and when it does, it can be challenging to determine when things will turn around. When customers experience bad services, they may never come back, especially if they receive satisfactory services at a competitor.

While this remains a concern for me, the good news for DG is they do have some strong competitive advantages that will likely give them some time to turn things around.

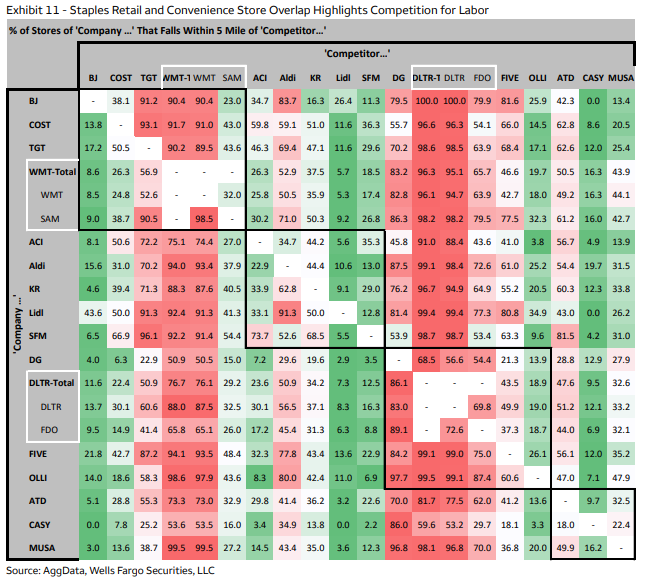

In a sense, a retail store can be a de-facto monopoly in a town if there is no other alternative nearby. I came across the following table on Twitter (h/t private account) which shows for half of DG’s stores, there is no Walmart within 5 miles. Similarly, slightly more than half of DG’s stores don’t have a FDO store within 5 miles. A former VP of DG mentioned on a Tegus call that the DG stores that have no competitor (WMT, FDO, or DLTR store) within 10 miles are usually the most successful stores. Again, FDO’s operational issues and a sluggish pace of store expansion was historically a massive boon for DG.

While Walmart may not seem like a direct competitor, customers do consider the trade-off between convenience and value. Dollar General has recently started talking about “investing” in price which essentially means their prices may be a tad bit expensive than competitors and need to be lowered to keep the value-convenience trade-off more in their favor. Interestingly, Walmart used to have a more direct competitive response to Dollar Stores: Walmart Express which were ~12-15k sqft stores, so almost double the size of typical Dollar Stores but <10% of the typical Walmart supercenters. Then in 2016, Walmart closed these stores which were largely acquired by Dollar General.

As alluded earlier, the local or even regional retailers will always have hard time matching Dollar General’s convenience AND value since they don’t have the purchasing power and negotiating leverage like Dollar General does with suppliers.

Overall, while assessing the competitive dynamics, we have to take into the context of alternatives available. If there is no FDO or WMT stores within 5-10 miles of a DG store, DG stores have a material competitive advantage. Such competitive advantage is quite durable in smaller towns (think ~1k-5k people towns) where the economic case for another dollar store may not be quite attractive for DLTR or FDO. On the other hand, areas that do have an alternative such as FDO or WMT store, there may be very little competitive advantage for DG and hence has to be mindful of matching or at least being very close to prices available in WMT/FDO. DG, of course, can make pricing decisions based on the competitive dynamics; their prices are not uniform across the country anyway.

But over time two things can simultaneously happen which may tamper the economics of DG stores: a) it is highly likely that the next 5k-10k DG stores in the US are going to be in areas that either have existing DG store (so can face more and more cannibalization) and/or there may be already a nearby FDO or WMT store which will necessitate a very tight convenience-value balance; b) FDO or WMT themselves will open new stores near DG stores, especially in relatively larger towns (think 20k or more population towns) which will also create some competitive pressure on DG stores.

Therefore, on the question of competitive advantage, I don’t sense a black and white answer for DG. Today, it seems half of their stores have material competitive advantage while the other half likely enjoy limited competitive advantage (the mix is likely lower than 50-50 since I don’t know what % of Dollar Stores do not have both FDO and WMT within 5-10 miles). Over time, this mix may become more unfavorable if FDO finally figures out their operational challenges. That’s perhaps a big if; but given a new management at DLTR/FDO and DG’s own labor challenges recently, it is a bit tense situation.

Things got a bit more complicated by some recent developments in government’s food stamps or SNAP program which helps feed almost 42 mn Americans, supermajority of whom are likely Dollar Store customers. As government significantly expanded the benefits following the pandemic, SNAP benefits (including the emergency allotments) was12.3% of total at-home U.S. food and beverage retail sales in 2022 vs just 7.1% in 2019 (estimates by HSA Consulting). Congress rolled back some of these benefits in December 2022. CBPP estimates that an average three-person household receiving SNAP will see their monthly benefit go from $759 a month to $592 a month, a 23% reduction for such a family. WSJ reported on this issue back in February 2023:

Net-net, Goldman Sachs expects overall SNAP benefits to decline 7% this year compared with the last—a reversal after at least three consecutive years of growth. Many households will also get smaller tax refunds this tax season compared with last year: After receiving pandemic-era boosts, child tax credits, the earned-income tax credit and the child and dependent care credit returned to 2019 levels for 2022.

Such reversal will likely lead to tough adjustments for many of these low-income households dependent on government food stamps/benefits programs. This may be a double whammy for Dollar General: a) many of their customers simply have their purchasing power slashed, and b) given the tight budget of these households, they will have even lower discretionary income. As a result, DG’s higher margin segments such as non-consumables (which are more discretionary purchases) may have difficulty keeping pace with consumable segment in the near-term.

While these near-term questions are quite relevant today, what about a bit more long term questions for Dollar Stores future? Let’s get to some of those questions.

From 2018 to 2022, DG’s store network grew by Mid Single Digit %. For the rest of this decade, it is perhaps likely that DG’s store network will grow at ~3-4% rate every year. But beyond the current decade, DG’s topline growth may become entirely dependent on SSS growth. DG has started expanding to international markets and opened its first store in Mexico in February 2023, but I don’t think anyone wants to assign much value to the international expansion just yet. Therefore, one of the key questions of paramount importance for terminal multiple is DG’s growth rate in “terminal” state when store expansion theme is (near) complete.

As discussed in section 2, SSS is primarily driven by store traffic and transaction amount per trip. Store traffic has been challenged over the last four years and it remains my key long-term concern for DG.

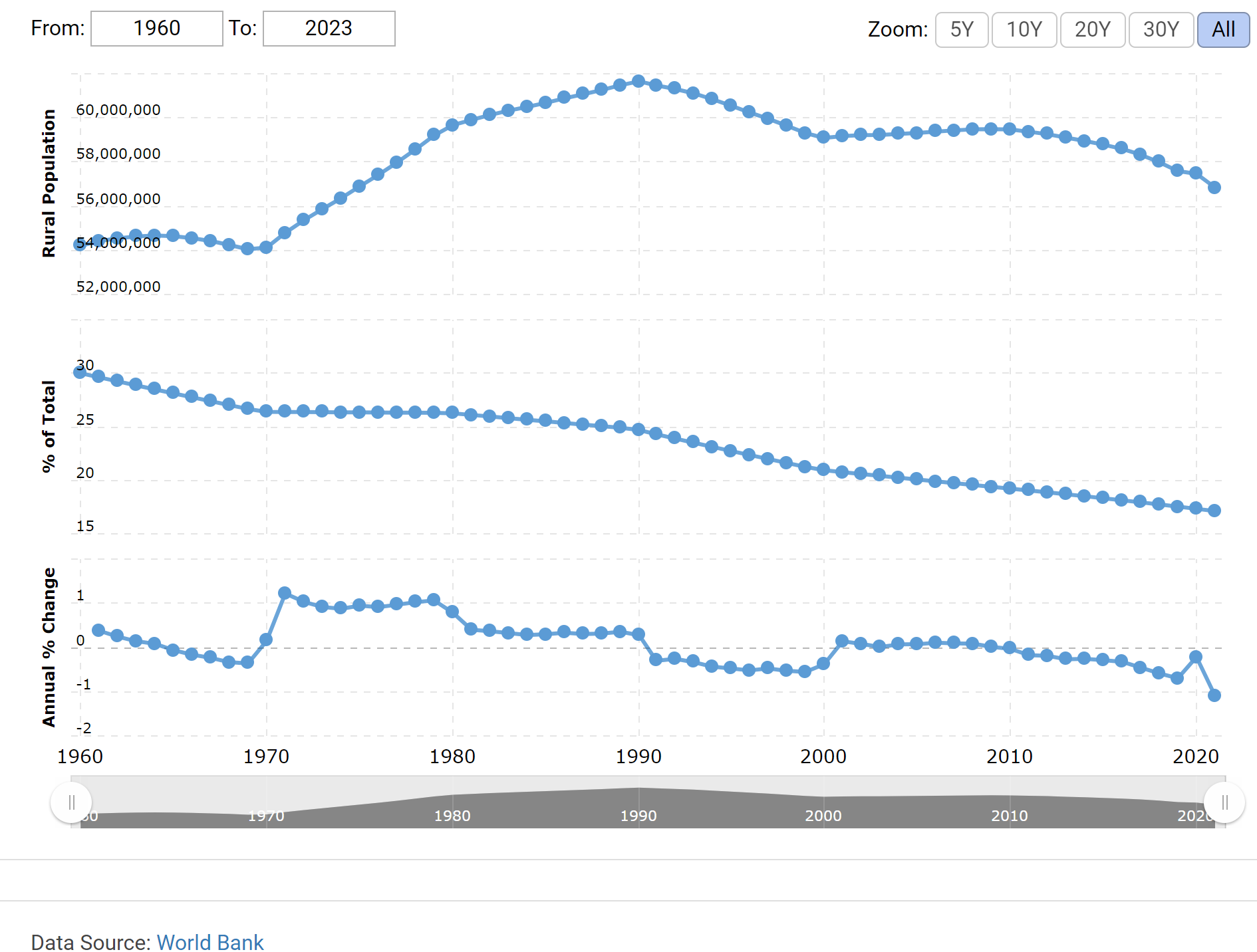

If you look at US rural population, you can see it has been declining since 2010. Given DG’s dominance in rural America, I wonder whether one part of the long-term SSS equation is simply secularly challenged. DG bulls may point out DG was hardly affected in the last 10 -12 years despite such population trend, but it is hard to imagine immunity for DG if this trend continues for the next decade or two. If you are a retailer in an area from where people are moving out, that will eventually pressure your economics. I’m obviously not saying DG stores cannot be profitable; all I am saying the growth algorithm will have big question mark once the store expansion will run its course and if rural population continues its trend. If store traffic is secularly challenged, topline growth will be dependent on transaction amount per trip which can be driven by overall inflation and higher(lower) priced mix of products on the store. While nominal growth can still be positive in the secularly challenged store traffic scenario, real growth can be minimal or even negative.

Of course, DG can open new stores in more urban or metro areas. But FDO may already be in these areas and unlike in rural areas, most urban/metro areas even low-income people have plenty of alternatives. DG may have to dance in a tight value-convenience range to maintain their competitiveness and operating margins and ROIC can be less attractive for these stores compared to what DG enjoyed in the last decade.

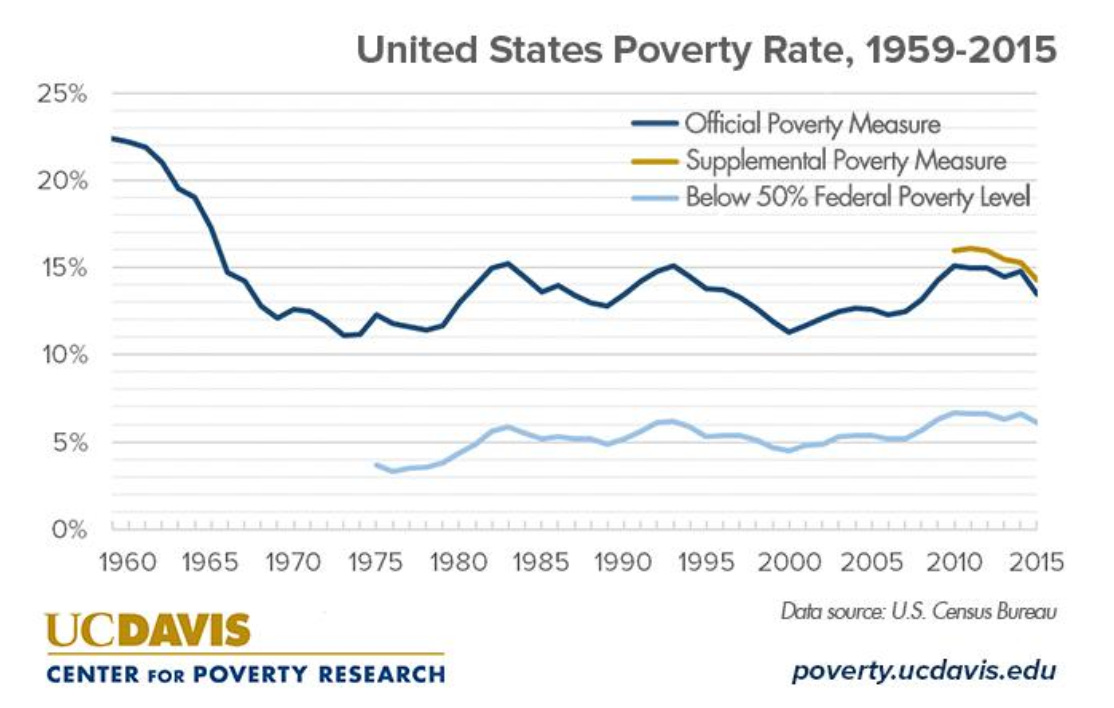

One other long-term concern some may ponder is whether Dollar Stores will have long-term relevance if poverty is largely eliminated in the US. That seems unlikely; while poverty rate rapidly declined from ~20% in 1965 to ~12-15% in 1975-1985, poverty rate has proved to be quite sticky. Whether it will remain this sticky may be more of a political, sociological, philosophical, and technological question that is above my paygrade, but I wouldn’t worry much about Dollar Stores being irrelevant anytime soon.

One thing that does worry me more is potential regulations that can derail the long-term growth plans for Dollar Stores. There has been a growing chorus recently about the potential negative effects of Dollar Stores on rural communities in perpetuating “food deserts”. Here’s one paper outlining what many local governments have done in response:

Since 2018, approximately 50 local governments in the U.S. have passed policies to curb dollar store growth. Among these policies are moratoria on new dollar store construction, as well as novel zoning ordinances to limit dollar store proliferation in specific areas of the municipality. By altering permitted, conditional, or prohibited uses in the zoning code, local governments are aiming to (1) limit the number of new dollar stores within a certain radius of existing dollar stores, (2) impose a temporary moratorium on new construction to gather evidence on the public health implications of dollar stores, and/or (3) ban new construction outright.

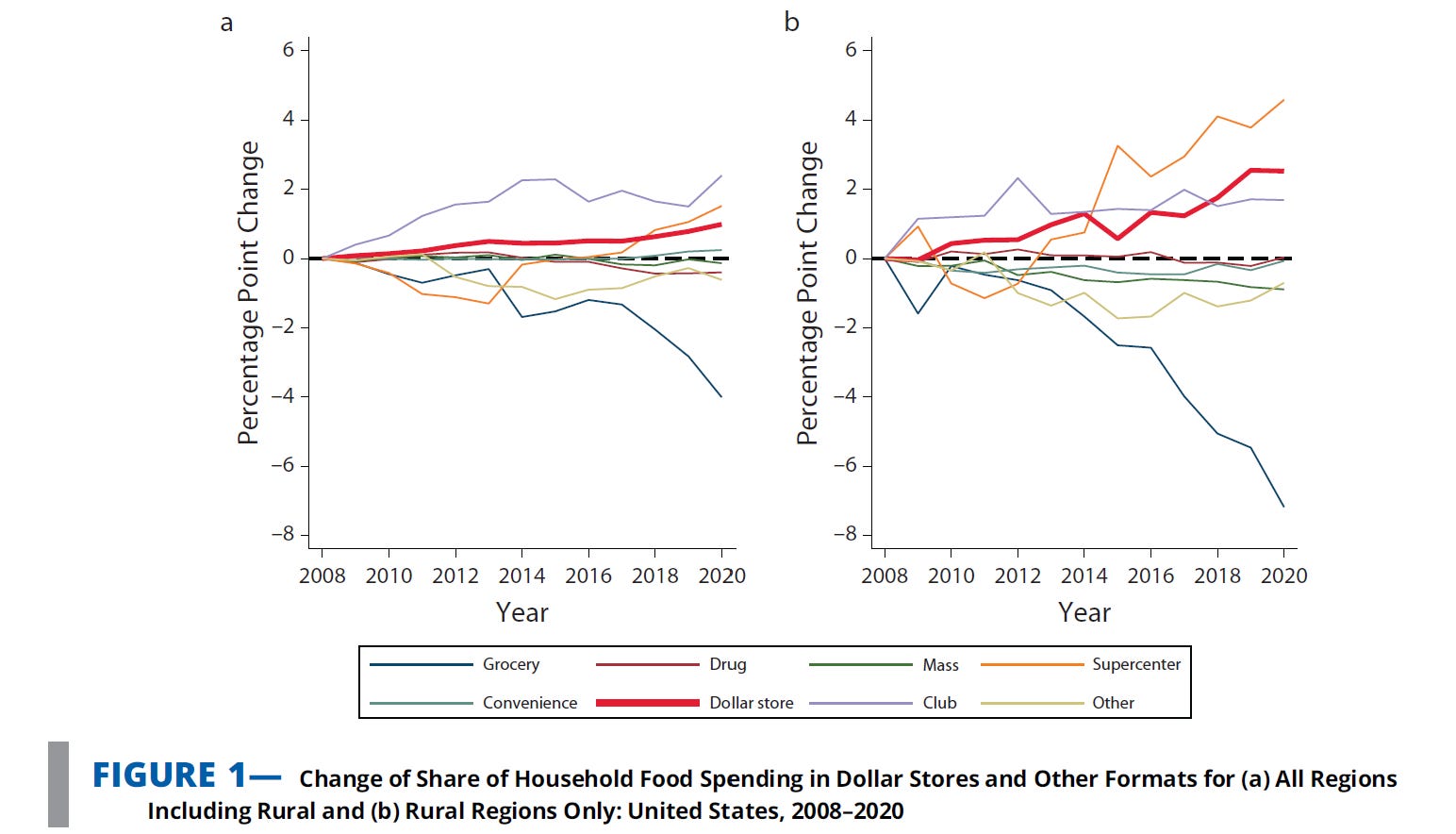

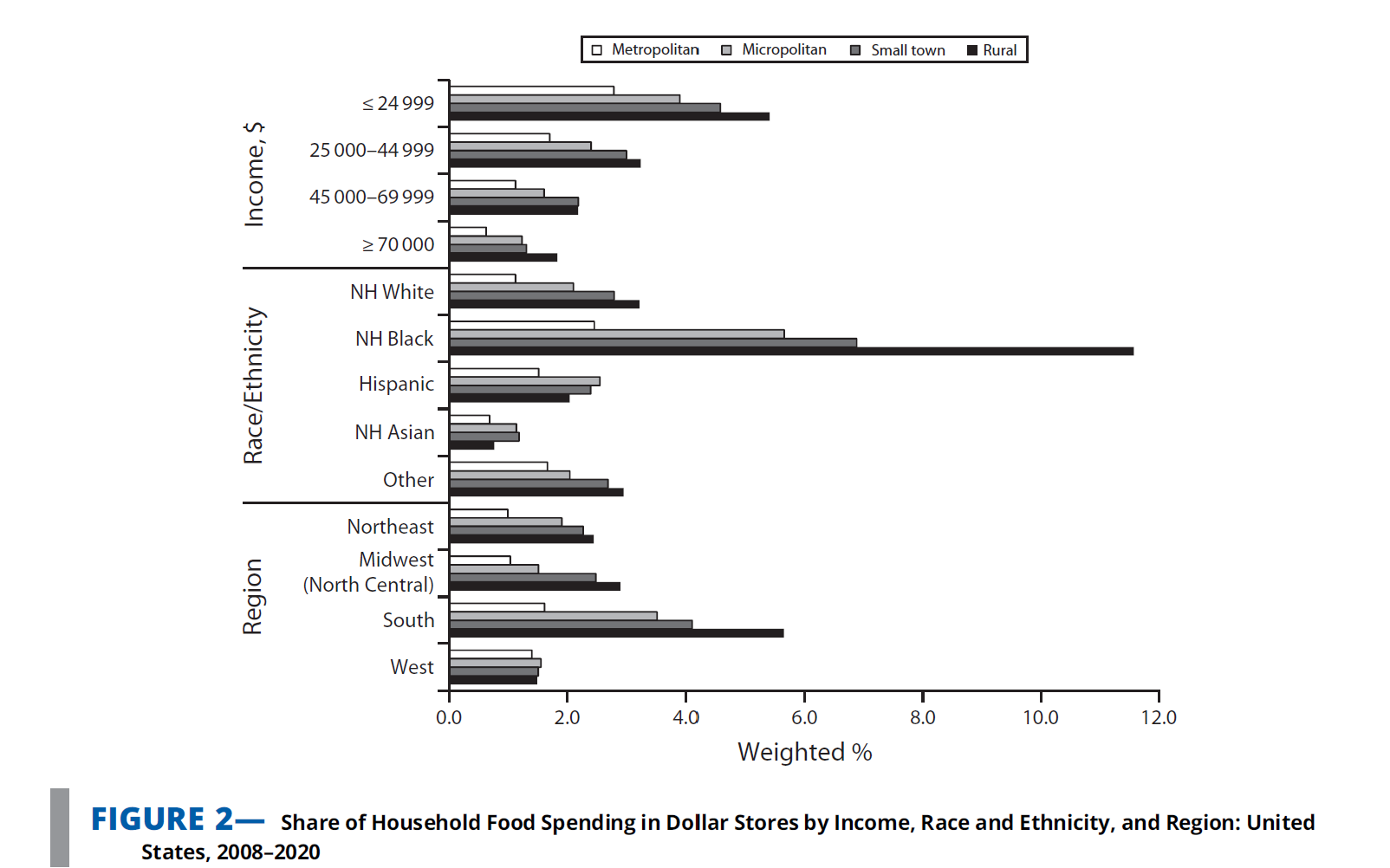

To understand these concerns a bit more, I read another research paper titled “Dollar Stores and Food Access for Rural Households in the United States, 2008–2020”. The paper indicates that while rural households food expenditure on dollar stores remains quite low, dollar stores are gaining share:

In 2008, households spent an average of 62.3% of their food budget in grocery stores. This number declined to 58.3% in 2020. This loss was picked up by club stores (2.4 percentage points), supercenters (1.5 percentage points), dollar stores (1.0 percentage point), and convenience stores (0.2 percentage point). Among households living in rural areas, expenditure shares at grocery stores decreased from 57.4% in 2008 to 50.3% in 2020. This loss was picked up mostly by supercenters (4.6 percentage points), dollar stores (2.5 percentage points), and club stores (1.7 percentage points). Notably, household spending at dollar stores in rural areas increased from 2.5% in 2008 to 5.0% in 2020. In fact, dollar stores were the fastest-growing food-retail channel in rural areas

Even though dollar stores’ share on food budget among rural household was only ~5% in 2020, the share is higher among the lowest income groups, among Black households, and in the South, all of which are core target markets for Dollar General. If the local towns become increasingly hawkish and stringently control dollar store expansions, Dollar General may be most exposed in the long term and they may be forced to revise their store network size over the long term. From the paper:

As income decreased, the share of food expenditures in dollar stores increased. Households in the South also purchased more food in dollar stores; within rural areas, households in the South spent the most, and those in the West spent the least. Perhaps the most notable group was rural non-Hispanic Black shoppers; these households spent 11.6% of their food budgets in dollar stores.

This paper did, however, mention that “empirical evidence is still lacking” in terms of establishing the deleterious impact of dollar stores on rural communities and encouraged more work on this topic. Given these concerns are relatively recent developments, I suspect more evidence may gradually come along to understand the impact of dollar stores. If such evidence turns out to be damning (TBD), more and more local towns can decide to introduce onerous regulations which can hamper store expansion plans for Dollar General. As alluded earlier, Dollar General’s launch of “DG Fresh” may be bit of a response to some of these concerns, so it is possible that instead of being labeled as primary culprit for creating food deserts in the US, dollar stores may end up being part of the solution, However, an expanded grocery offerings could make things quite challenging to maintain DG’s low operating cost strategy; you simply cannot run a store filled with perishable items with one or two employees. The logistics and supply chain of perishable items are also more difficult than what dollar stores have traditionally managed over the last few decades. Therefore, there can be pressure on margins if dollar stores end up being the primary conduit to solve food desert problems in the US.

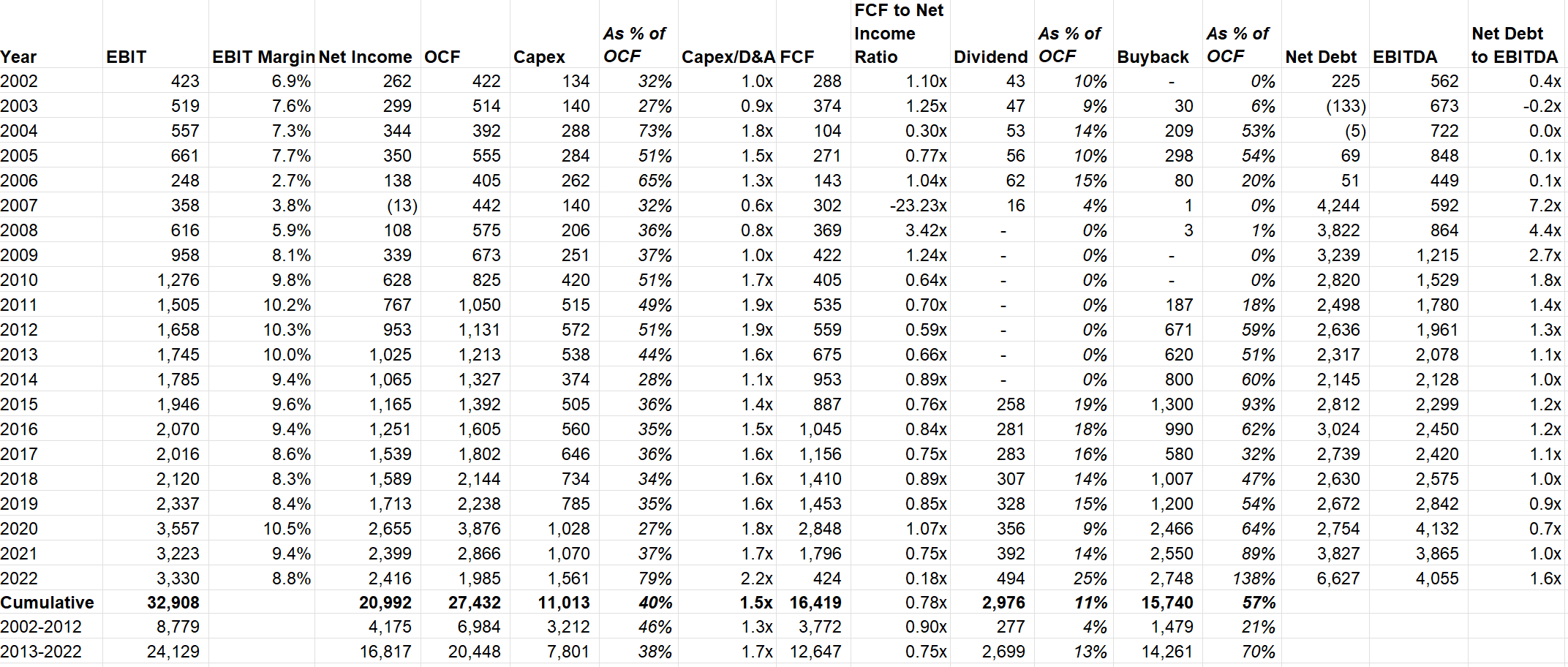

I am a fan of neither DG’s capital allocation nor their management incentive system. Let’s start with their capital allocation.

Over the last ten years, DG generated ~$20 Bn Operating Cash Flows (OCF), 38% of which was reinvested in capex, 13% was used to pay cash dividends, and a whopping 70% to repurchase shares. Why am I not a fan of such capital allocation?

Back in 2016 investor day, DG outlined their total store opportunity in the US to be ~25k. Their store base was roughly half of that at that time, and they told investors their IRR for incremental store was consistently ~20% with payback period slightly less than two years. If you have reinvestment opportunity with 20% IRR potential, I am not sure I can get behind using capital to buyback shares instead of reinvesting more in capex. Sure, they spent ~30-40% of OCF in capex since then, but why not 80-100%?

One way it could still make sense is if their stock was just too cheap and IRR from deploying capital to buyback stock was >20%. You could perhaps make that case during 2016-19 period, but it is difficult to reconcile their capital allocation over the last three years. During 2020-2022 period, DG generated $8.7 Bn OCF and used $7.7 Bn of them to buyback shares at multiples considerably higher than DG ever traded in the last 10 years; much of their buyback over the last three years happened at prices higher than it is trading today. I would be much more forgiving if DG actually didn’t have reinvestment opportunities, but management, in fact, raised long-term US store network opportunity from ~25k to ~30k which implies another 10k stores yet to be opened. So, DG cannot play the “Return Of Capital” card since given their reinvestment opportunity, their capital allocation should firmly rely on “Return On Capital”.

Even if IRR for these incremental stores are lot lower than 20%, it’s still likely ~12-15%? If that’s the case, why exactly is DG waiting to open these stores gradually over time instead of aggressively pursuing this opportunity by reinvesting almost all of their OCF? Even if IRR for these stores is 10-12%, I would still prefer capex over buyback because such expansion would materially entrench DG’s moat.

One would think FDO and WMT are doing the same store location analysis DG has been conducting. If DG identifies, for example, a rural town in Idaho as a good location for a DG store, shouldn’t it open that store there as soon as possible? What if FDO or WMT goes there first? IRR for late entrants in a rural town is extremely likely to be lot lower than early entrant (assuming the early entrant doesn’t fumble too much in their operations). If from 2015 DG reinvested their OCF much more aggressively and got to their full US store opportunity base in 2023-25, DLTR (especially FDO) management would be gasping for air today. You could say FDO is indeed gasping for air even after DG’s somewhat perplexing capital allocation; I may acquiesce but also wonder whether DG has been a bit lucky in this case. After all, they tried very hard to acquire FDO too and it was their failure to acquire FDO that may have shielded them from another bout of misallocation of capital. In any case, it is perhaps prudent not to allocate your capital assuming your competition would be inept. If you have reinvestment opportunity, it is likely just a superior strategy to pursue it aggressively regardless of your competition’s current state.

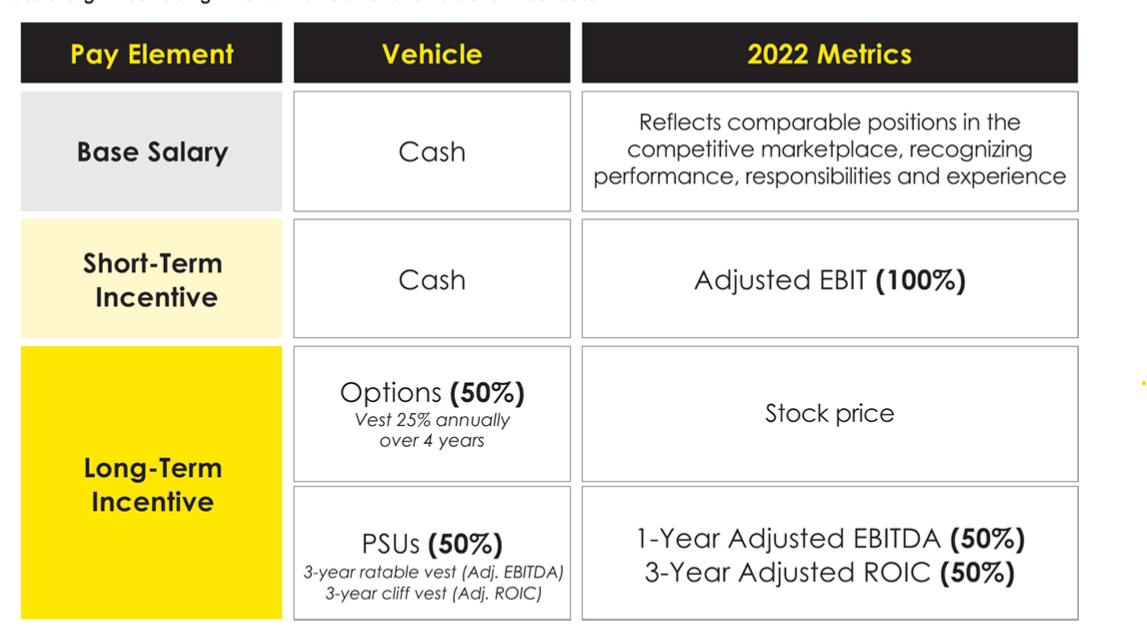

Let’s talk about DG’s management incentives now.

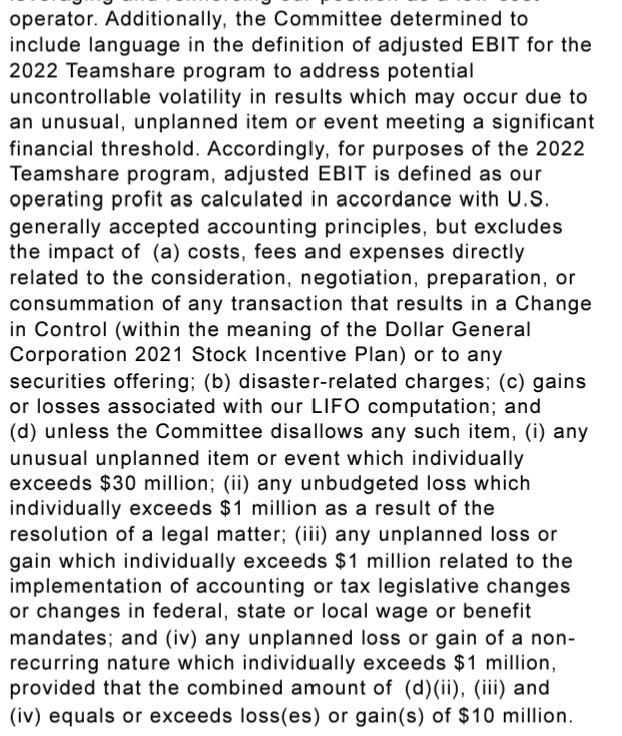

DG management is paid an annual cash bonus based on “adjusted EBIT” metric (more on this soon). It’s the long-term incentive that I find much more problematic.

How does DG define “adjusted EBIT”? While the adjustments are plentiful, they don’t do egregious things such as adding back SBC. In fairness, even though it may seem there are too many adjustments at first glance, these adjustments seem reasonable to me.

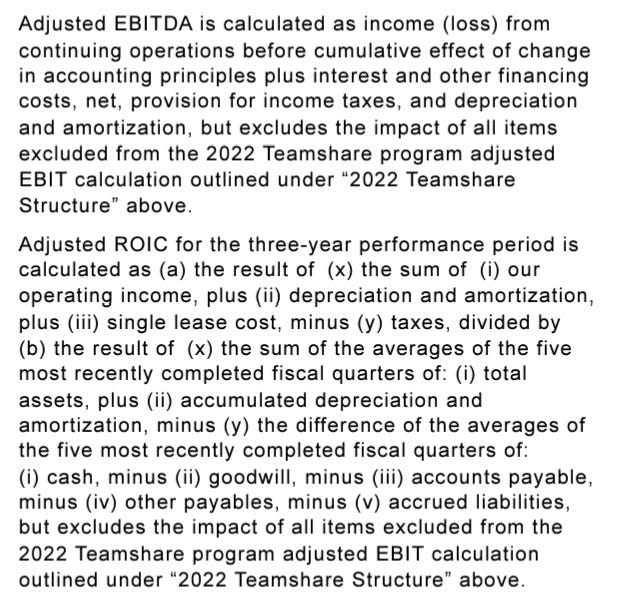

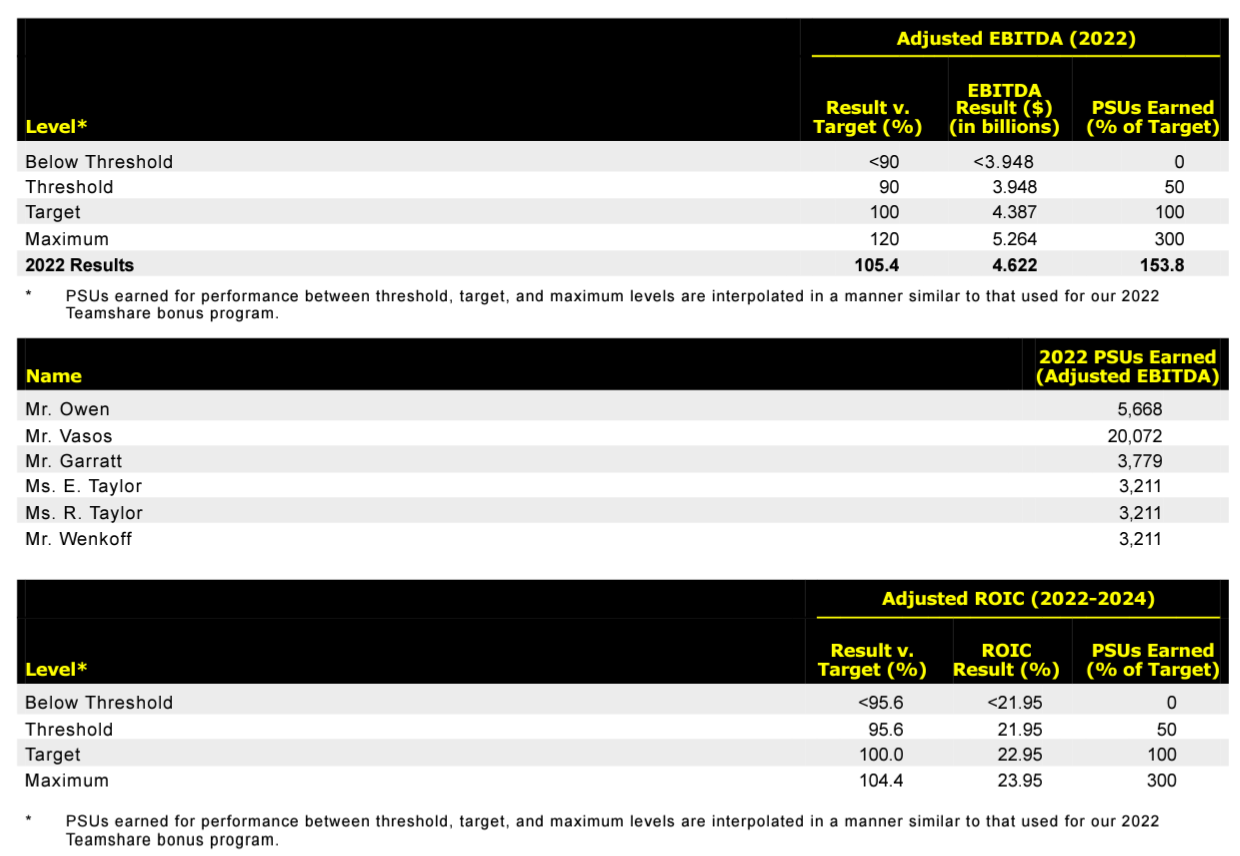

What doesn’t seem reasonable to me is tying half of their long-term incentives to Adjusted EBITDA and “ROIC”. I’m sure even many recent college graduates can explain why EBITDA is not a good metric to use to evaluate a management team running a brick and mortar retail company. But you probably need to hire compensation consultants to help bury the truth of the reality of depreciation expense for a brick and mortar retailer. To calculate ROIC, they use EBITDA in the numerator; at least their denominator is somewhat consistent here given they add back all accumulated depreciation and amortization to total assets. I would, however, prefer to use Net Operating Profit after Tax (NOPAT) divided by average net working capital+ average fixed assets to calculate ROIC.

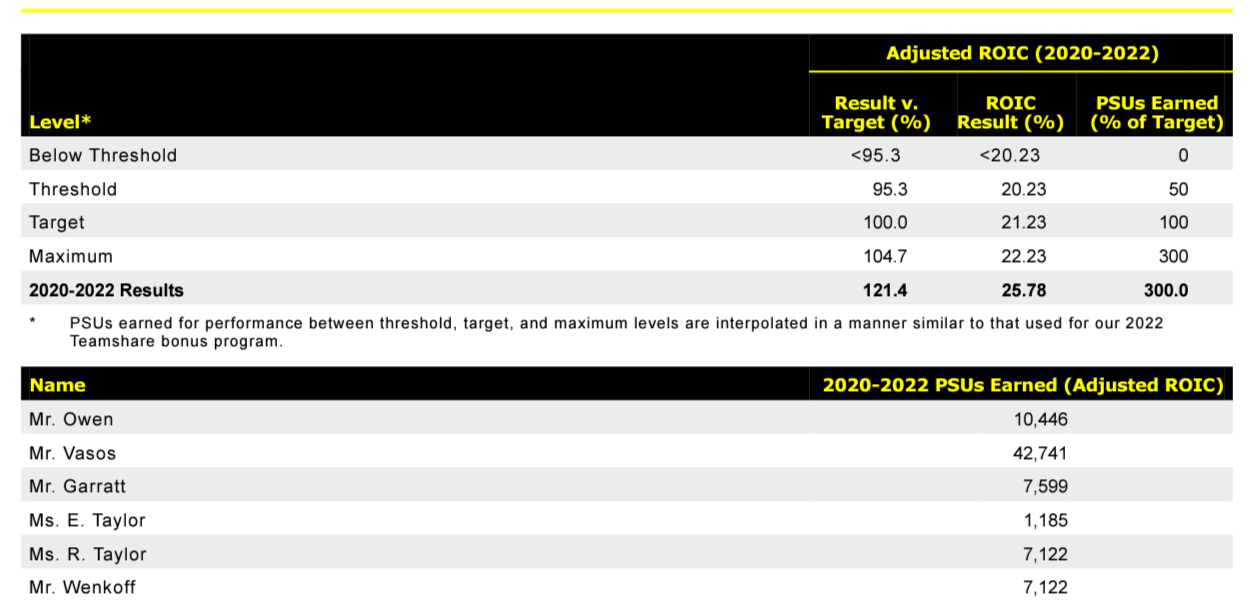

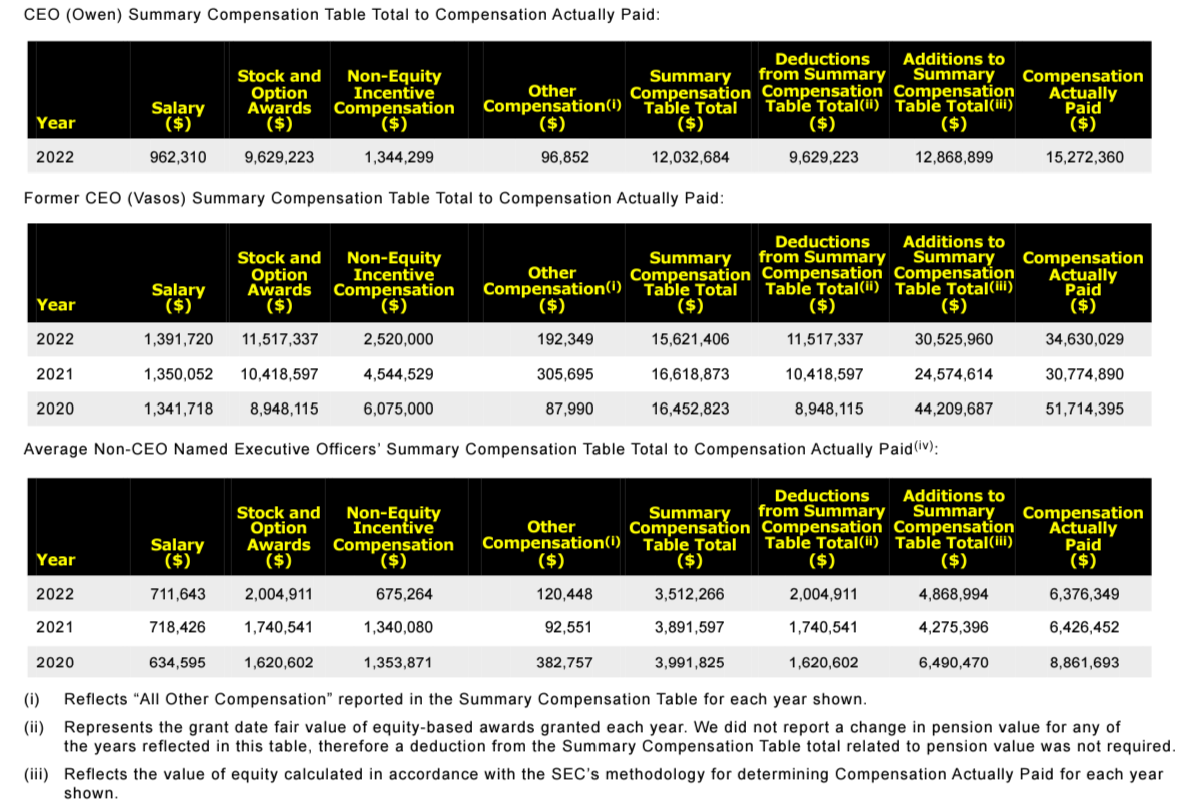

Moreover, the way the incentive is structured is also not quite admirable. While I appreciate that PSUs can be zero if the actual result is below 90% of the target, I am not thrilled at 300% payout for achieving 120% of the target (actual payout is interpolated between target and actual results). Moreover, if you look at “Summary Compensation Table” on DG’s latest proxy statement, you would see the former CEO (DG got a new CEO in November, 2022) received total $49 Mn during 2020-2022 period. The actual compensation paid to the former CEO was $117 Mn during this time. Part of this difference was helped by rising stock price (options are worth much more when stock goes up), but also by the generous target payout related to adjusted EBITDA and ROIC. While regrettably DG’s peer DLTR also focuses on adjusted EBITDA to evaluate management’s performance (I’m staring to appreciate Munger’s deep aversion to compensation consultants), at least their max target payout is capped at 150%. Moreover, some of these target metrics are suspiciously too close to each other; for example, 2022’s ROIC target threshold to receive 100% payout was 21.23% whereas to receive 300% payout, ROIC needed to be just one percentage point higher: 22.23%. The actual result was 25.78% which led to 300% target payout for executives.

If you entice a management team that they can get 300% target payout by posting ROIC just one percentage point higher, there is enough financial engineering available in the world to reach such targets. If shareholders overpay Named Executive Officers by ~$20-30 mn per year thanks to these generous comp structure, it can add up over time, especially for a low margin industry such as brick and mortar retail. Imagine instead of paying the former CEO $117 Mn during 2020-2022, we could pay him ~$50-60 Mn (DLTR CEO got paid ~$54 mn during the same time, and DLTR and DG stock were up both ~60-65% during 2020-2022) and reinvest the $70 Mn in lowering prices for customers or better service by investing more labor hours in the stores. These may seem small things but in a cut throat industry such as retail, these may prove to be consequential in the long term.

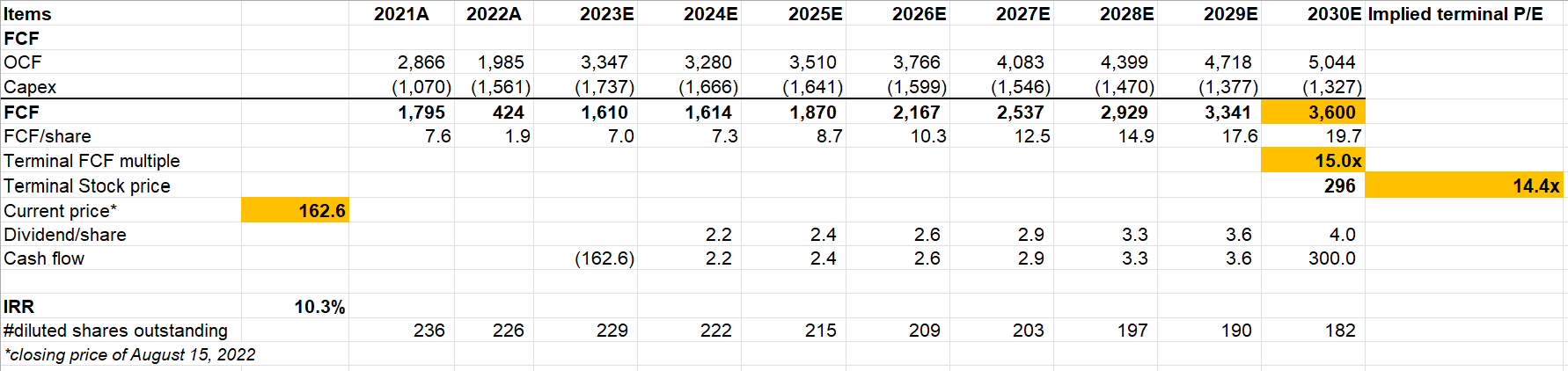

If you are reading my Deep Dive for the first time, I strongly encourage you to read my piece on “approach to valuation”. Please read it at least once so that you understand what I am trying to do here. I follow an “expectations investing” or reverse DCF approach as I try to figure out what I need to assume to generate a decent IRR from an investment which in this case is ~10%. Then I glance through the model and ask myself how comfortable I am with these assumptions. As always, I encourage you to download the model and build your own narrative and forecast as you see fit to come to your own conclusion. None of us have the crystal ball to forecast 5-10 years down the line, but it’s always helpful to figure out what we need to assume to generate a decent return.

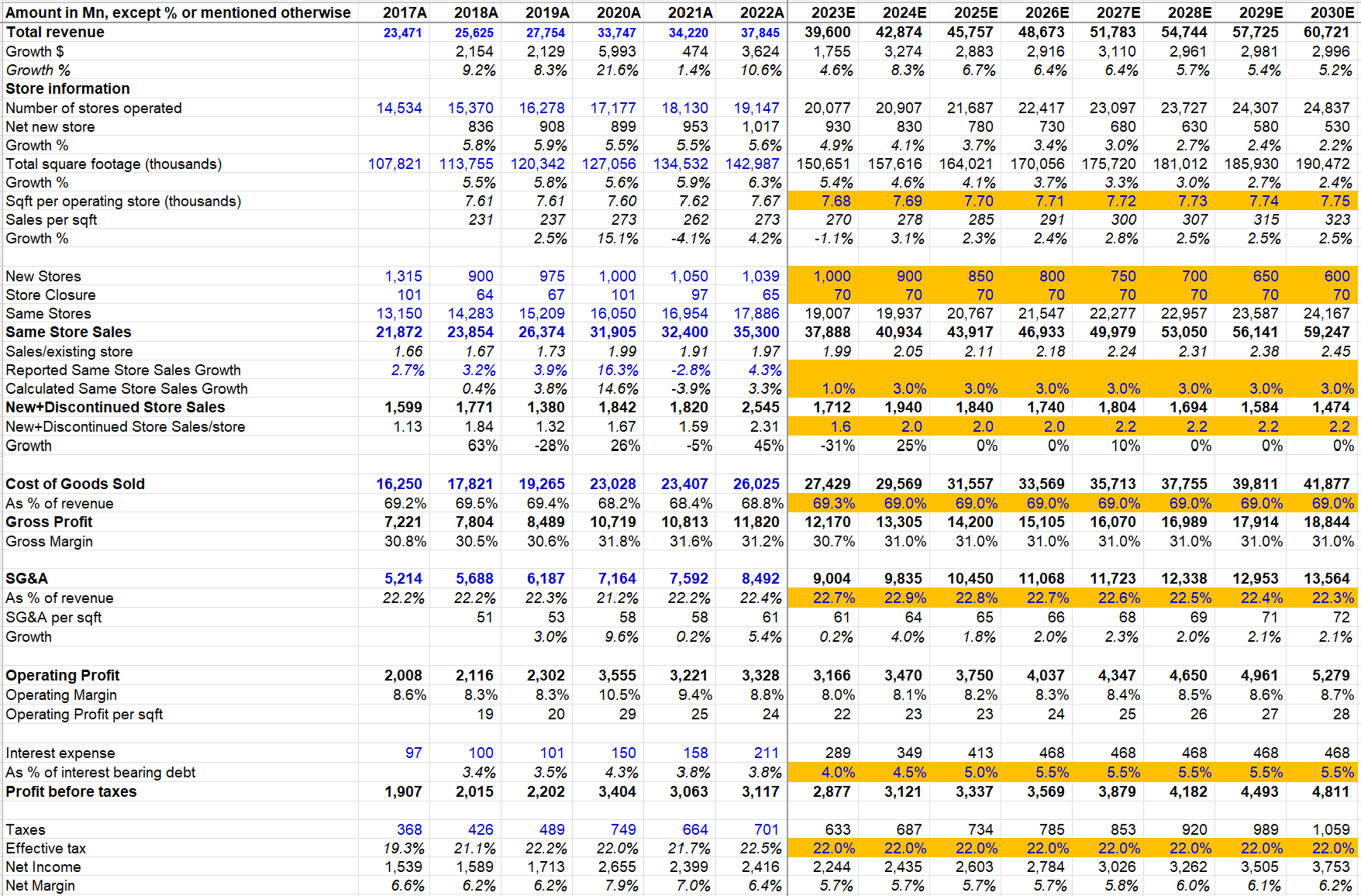

Given the likelihood of increasing regulations in many local towns, I am a little skeptical of DG’s claim of 30k US store opportunity. As a result, I modeled a much slower store growth and reached ~25k store size in 2030. However, considering average store size is gradually increasing, sqft growth is modeled to be slightly higher. Same Store Sales (SSS) growth is assumed to be ~3% during 2024-2030 which was also the average SSS growth during 2012-2019 period before the pandemic bump in 2020. 2020 SSS is such an anomaly that it makes me wonder whether SSS may continue to be slightly weaker than 3% for longer than I modeled here.

SG&A per sqft is modeled to grow at slightly higher pace than sales per sqft for 2023-24 considering DG likely needs to make further investments in labor hours. Beyond 2024, I modeled sales per sqft to grow slightly faster than SG&A per sqft. As a result, operating margin is modeled to increase slowly over time but still 2030 operating margin is modeled to be ~180 bps lower than DG’s peak margin in 2020. For what it’s worth, I’m ahead of consensus in terms or revenue and largely in line (or slightly ahead in some years) in terms of EBIT.

Given rising interest rates, I expect new issuance of debt to be more expensive than it had been in recent years. But this trajectory entirely depends on how interest rate will move going forward. Net debt to EBITDA is kept at ~1.0x which was largely the case for much of 2017-2021 period.

Valuation

To generate ~10% IRR, I had to assume 15x FCF multiple in 2030 (or 14.4x P/E multiple). Is 15x terminal multiple too cheap? Let’s imagine we are in 2030 today and we are looking at DG’s stock. What would an investor in 2030 likely see at DG for 5-10 years beyond that? It’s possible the store base will grow at ~0.5% per year. Given secular decline in rural population and hence long-term pressure on store traffic, I am skeptical that 3% SSS long-term growth is possible to sustain, so it may be more like ~2-2.5%. Overall, topline can grow at ~3% and if we imagine a better incremental operating margin, I can see DG’s operating earnings to grow at ~4% in 2030-2040 period. If that’s the growth profile and you want ~10% IRR from your stocks in 2030, it is hard to see you paying higher than ~15-16x multiple in 2030. A ~6-7% earnings yield is required (assuming all of which will be returned to shareholders via dividends and buybacks given low reinvestment opportunity then) to generate ~10-11% IRR for a company growing earnings at ~4%. Of course, market may deem ~10-11% IRR to be a too steep required return if interest rate comes down a lot, but those things are my (and likely everyone’s) paygrade.

Dollar General has been a beloved compounder until the current steep drawdown. Despite the unprecedented drawdown, I am of the opinion that there hasn’t been a material dislocation from DG’s intrinsic value. While I can see investors make decent IRR from here, it’s unlikely to be very attractive (probably more of ~8-11% IRR than ~15-18% IRR). I am also somewhat wary of brick and mortar retail companies going through bit of an operational challenges as these things almost always take longer than most investors assume it will take. One way DG can surprise to the upside is if we enter a recession soon as it can be potentially beneficiary of trade downs by consumers in a recession scenario. Such countercyclical nature of DG is what truly enticed me to study the company in the first place, but I am slightly underwhelmed by their capital allocation philosophy and the suboptimal incentive structure. I, however, try not to be too dogmatic (at least not yet but maybe eventually once I have much greater breadth of companies under coverage) if stock price compensates for such flaws. Therefore, I wouldn’t quite rule out owning DG ever, but I would need to see a plausible ~15% IRR scenario to get interested.

Portfolio Discussion

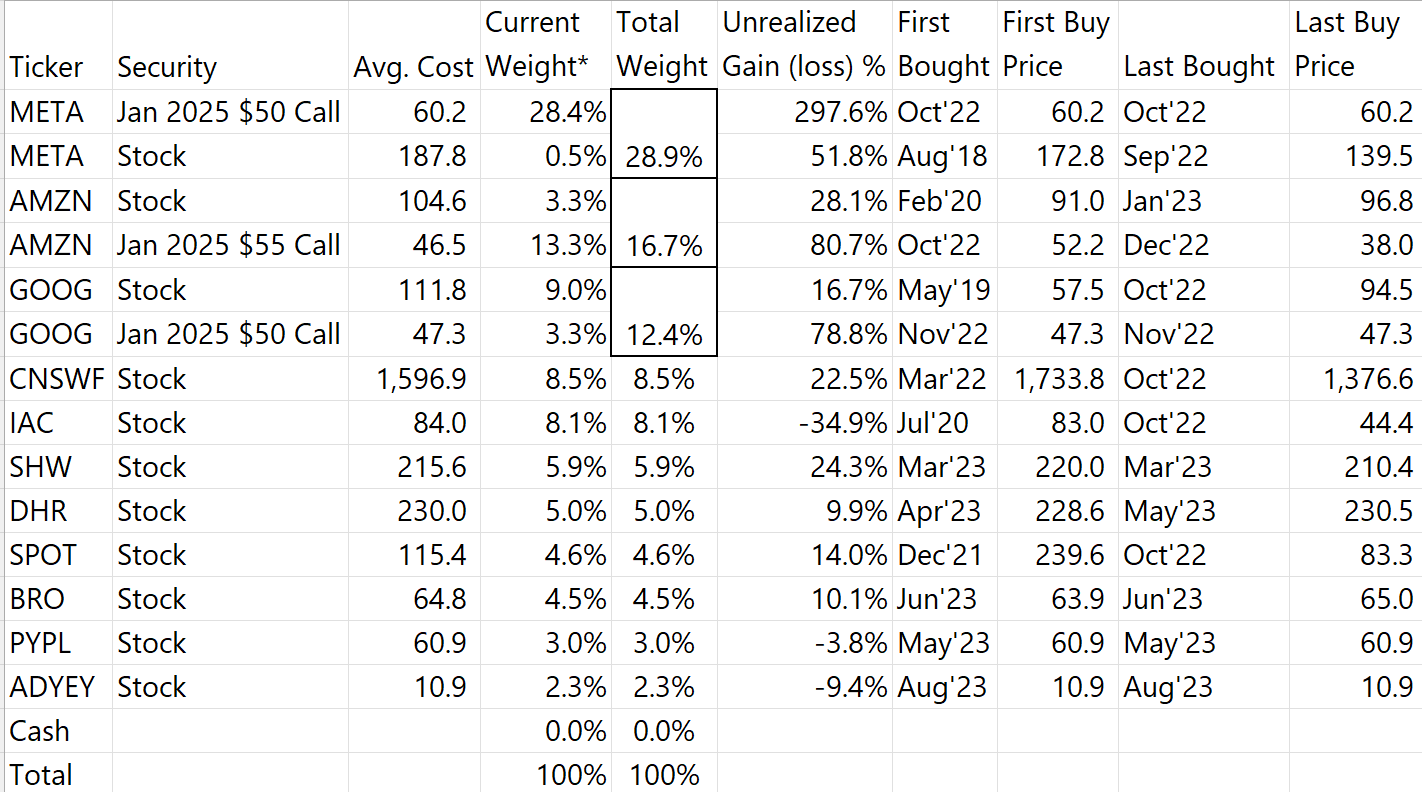

Please note that these are NOT my recommendation to buy/sell these securities, but just disclosure from my end so that you can assess potential biases that I may have because of my own personal portfolio holdings. Always consider my write-up as my personal investing journal and never forget my objectives, risk tolerance, and constraints may have no resemblance to yours.

Since last month, I have trimmed some of my “Google Jan 2025 $50 call options” at $84, Amazon shares (at various prices between $135 and $140), and completely sold out of Autodesk at $216 to fully payoff my student loan.

In my 2022 letter, I introspected and identified three specific mistakes:

a) I considered investing in a company run by Jack Dorsey to be a mistake. I sold Block (formerly known as Square) in early 2023.

b) I thought I acted a bit naively in evaluating Spotify’s advertising segment, especially the podcast business. Such a mistake led me to start buying Spotify in the $240s, but by the time I started to appreciate the nature of my mistake, market already punished the stock to an extent that I thought was a bit extreme. While I decided to average down, I was of the opinion that Spotify likely deserves a lower weight in my portfolio (it was ~9% in Dec’22). Over the last couple of months, I have sold Spotify at various prices between $160 to $180 to lower its weight in my portfolio to 4.6% now.

c) Another persistent mistake I used to commit was to not take into account of SBC from my terminal year FCF which would inflate the terminal value of the companies. I paid for this mistake by starting to buy Autodesk at ~$300 in March 2021 and continued to average down as the stock kept going down to make the average cost $230. After I realized my mistake about SBC, I avoided averaging down on the stock any further. I started selling some at ~$200 in Dec’22 and sold the rest this month at $216. Autodesk remains a moaty business, but the attractiveness of its valuation was significantly misperceived by me. Autodesk may do well from here, but it is unlikely to beat my borrowing rate on student loan.

Here’s another thing that I highlighted in my 2022 letter: “I own Amazon, Google, and Meta. I don’t quite share the market's skepticism about the durability of the supremacy of these companies. Perhaps I am in denial, and there are indeed credible risks against each one of them. But amidst the bearish sentiment when we can suddenly sense risk everywhere, I am very much willing to underwrite certain risks.”

Underwriting those risks proved to be quite fortunate so far in 2023, but I would remind readers that risk is omnipresent regardless of the movement of stock prices; there is no risk-free return in the stock market.

There is a material probability that EU may ban behavioral advertising altogether and if other countries feel motivated to follow EU’s footsteps in the future, it can create a potentially very uncomfortable scenario for Meta (if you are curious about my thoughts on this issue, read this). For Google, there are concerns whether Meta’s impending chat bot launch may affect their overall share in digital advertising and there are still questions on long-term generative-AI enabled search economics. Similarly, Amazon’s foray into shopping discovery and contextual advertising can also potentially make things slightly unfavorable for Meta; it is likely a very smart move by Amazon and sort of TBD for Meta. On the other hand, Amazon’s other bets losses remain bit of a mystery and if Amazon’s stock price keeps rising, one may need to form a more concrete opinion on “other bets”. In the stock market, questions are always evolving and as big tech (Meta, Amazon, Google) remains an outsized part of my portfolio, I will remain a diligent student of these businesses. The valuations for these stocks remain attractive and while there are credible risks, I do not consider them existential and expect each of them to endure through any short-term hiccups.

Some businesses (such as Sherwin Williams, Brown & Brown, and Constellation Software) that I own are quite low maintenance stocks. We probably all have something better to do than reading 20-page earnings transcript of Sherwin Williams from which I am unlikely to learn anything new about the business. For businesses such as this, I mostly read the press release and unless something jumps out to me, I do not read the transcript. For some of these low maintenance stocks, instead of doing quarterly recaps, I will probably do an update on these every two/three years to assess more closely whether the initial evaluation of the business quality largely remains on track. Given the initial work (I have published Deep Dives for all three companies), I have definitive ideas about at what valuation multiples I will be uncomfortable holding them, so I won’t necessarily be asleep if these stocks end up reaching the stratosphere.

That leaves three other stocks in my portfolio: Danaher, PayPal and IAC. I don’t have much to add on Danaher (see section 6 of May 2023 Deep Dive for my latest thoughts on Danaher). On PayPal, admittedly it is not a very high conviction stock for me and while I think upside can be debatable from current stock price, downside is likely limited unless the business implodes from here which I consider unlikely. With almost no leverage and quite profitable core business, the new CEO shouldn’t have a hard time in creating value for the shareholders. Nonetheless, the competitive concerns are real and while I expect secular forces of digital payments to outweigh competitive concerns, I would be patient before adding more here. I will also be patient with IAC even though it certainly seems to be in bit of a disarray. I’m not quite thrilled at how things are going at IAC, but also not as underwhelmed as the current stock price implies.

I also just opened a new position in Adyen yesterday. See my latest thoughts on the stock here.

My current portfolio is disclosed below:

Recommended Content

- Academic papers on Dollar Store impact on communities: here, and here

- Alex Morris’s Substack; no specific link but he wrote several pieces covering discount retailers which was helpful for me during my due diligence.

Disclaimer: All posts on “MBI Deep Dives” are for informational purposes only. This is NOT a recommendation to buy or sell securities discussed. Please do your own work before investing your money.