Goldman CEO David Solomon's Most-Loyal Deputy Tested by Mutinous Part…

Length: • 6 mins

Annotated by ham tarek

Think Bigger:See how we drive impact, create opportunities and power decisions

Wealth|Finance

By Sridhar Natarajan and Sonali Basak

August 16, 2023 at 10:00 AM UTC

The smell of seared red meat — $180 porterhouse, to be precise — hung in the air as bankers and traders from Goldman Sachs bluntly sized up their CEO.

In a once-unthinkable public display, a boisterous crew of senior managers gathered at an upscale Manhattan steakhouse last month and soon veered off their anodyne agenda. The conversation turned to the company’s failings and, in particular, those of its leader, David Solomon.

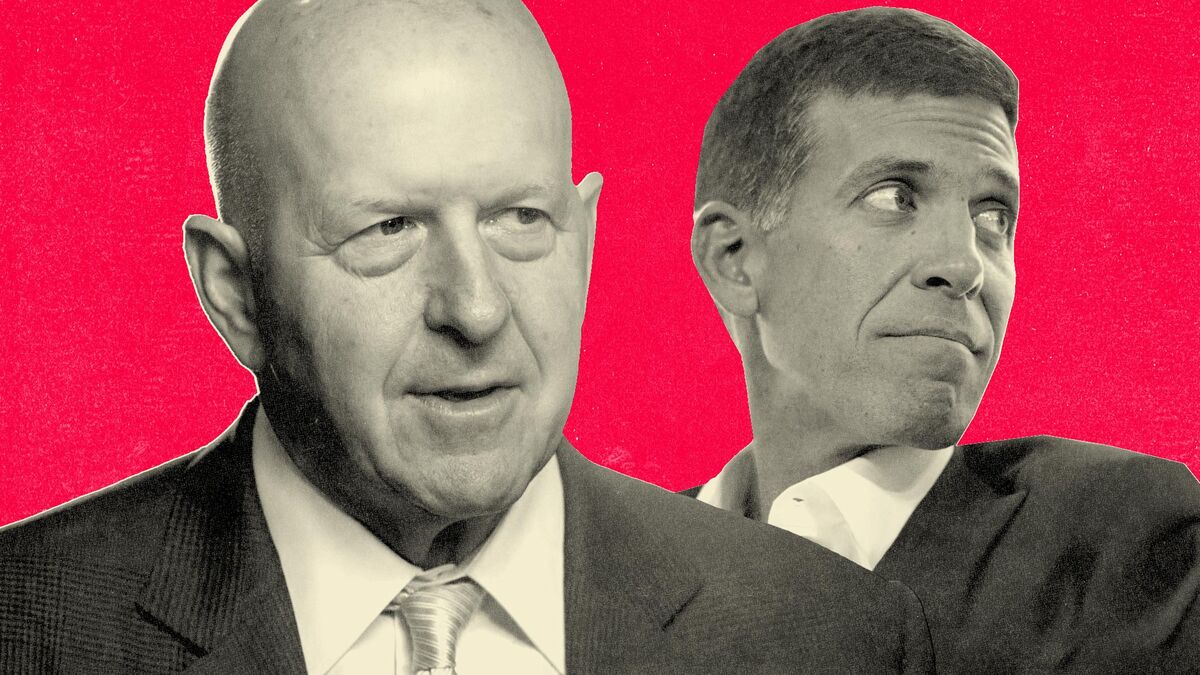

Their audience that evening, Goldman President John Waldron, sat across the white-linen-topped table and listened patiently.

Such dissent has become an alarmingly frequent occurrence at Goldman Sachs Group Inc., creating awkward moments for senior executives — and none more so than Waldron, the bank’s second-in-command.

The 54-year-old dealmaker has spent his three-decade career ascending Wall Street’s rungs behind Solomon to reach the financial industry’s most rarified air as the CEO-in-waiting at the powerhouse investment bank. But as bitterness festers in the ranks this year over Solomon’s leadership, Waldron is being pressed by colleagues to pick a side: Beat his own path to win over disgruntled executives, or risk being seen as an affable clone of the CEO.

And as the frustration spills into public view, many in the firm’s ranks keep wondering: Where does that leave John Waldron?

“What do you do if you’re the No. 2?” said former Goldman partner Robert Mass, who spent 27 years at the company. “Do you distinguish yourself and show you’re different, or do you show support?”

The irritant at Goldman isn’t the usual corporate woe of lackluster performance. Instead, it’s the CEO’s brusque leadership, unpopular changes and bold expansion into retail banking. That expensive and ultimately failed misadventure flamed out right when markets turned, biting into profit and pay.

Solomon and Waldron are known to be in sync on the company’s strategy shifts. But as Solomon, 61, long brushed off critics, Waldron played his foil — the diplomat. Over the past year, he has listened to and acknowledged frustrations without outwardly betraying his boss. The longtime banker to the Murdoch family knows the pitfalls of bruising succession battles.

Waldron has eschewed overtures from other firms, including Carlyle Group Inc. — moves visible to Goldman’s board. Still, in hanging around so long, he risks getting Gary Cohn’d. The former Goldman president waited a decade for his turn in the corner office, only to watch that prize slip away.

What’s striking about the tensions at Goldman is how apparent they have become. In June, BlackRock Inc. CEO Larry Fink — whose firm ranks as Goldman’s second-biggest shareholder — casually opined on television that there’s an obvious “schism” within the bank.

“There are all kinds of alliances that are within firms like this,” said Bruce Heyman, who spent 33 years at Goldman before serving as the US ambassador to Canada. “Those alliances will most likely get tested if publicity continues at this level.”

Talent can start to head out the door, taking a toll on business, he said. “It’s a risk to Goldman that clients become uneasy, and they begin looking elsewhere.”

Under Solomon, the 154-year-old firm has chalked up record annual profits. The stock has climbed almost 50% since he took the helm. The core investment bank has gained ground with clients, and the firm’s fundraising for alternative investments has gone better than expected. But at a trading house where red pens are frowned upon because the color denotes losses, the missteps are put under a microscope.

Executives have been parsing Waldron’s every eye roll or shrug to detect any sign of distance from the boss.

Then in July, he lit up the rumor mill. In a conversation with another set of senior dealmakers in the Hamptons about current business challenges, Waldron observed that whoever is running the shop roughly two years from now will likely sit atop a much cleaner firm. The remark ricocheted around Goldman as bankers wondered whether he was hinting at a planned leadership handoff, a succession timeline or, at the very least, his patience.

A company spokesperson said Waldron's remarks were misconstrued and that he was just talking about when the firm would deliver more stable returns. “The leadership team is focused on executing our strategy and the performance of the business, not on speculation,” said the spokesperson, Tony Fratto.

‘David & John Show’

Waldron and Solomon trace their ties to Bear Stearns in the early 1990s, where Waldron got his start as an investment-banking analyst and Solomon was already hawking junk bonds. Solomon defected to Goldman first, then lured Waldron, eventually taking him up the ladder.

“I was disappointed when he went to Goldman, but with David going, they were very close, so I understood,” said former Bear Stearns CEO Alan Schwartz. It's hard to say who’s going to be a future CEO, he said, but Waldron “has all of the makings of a great CEO.”

In 2018, Goldman’s board named Solomon CEO, and he appointed Waldron sole president.

Goldman CEO's Loyal Deputy Is Tested by Mutinous Partners

At a firm that prides itself as a collective of ambitious, money-making merchants, the new boss quickly made clear he was willing to try a new form of leadership. Solomon said all that mattered was the view of the top two guys, calling it “The David & John Show.”

That has prompted some executives to question why Solomon should shoulder the blame alone when Waldron, who’s also chief operating officer, was in charge of executing the chief’s vision. Such misgivings have gotten airtime as the firm dealt with bloated headcount and repeated culls, the fallout of slotting the wrong executives in leadership posts, and the failed consumer bank that Solomon had vowed to make an industry champion.

Waldron has proactively positioned himself as righting the ship — dismantling the retail bank and owning up to some wrong appointments — while pleading for a little more time to make the necessary fixes.

Losing the `M’

He also cuts a stark contrast with Solomon in other easily visible ways.

Solomon has earned a reputation as a ritz-seeking, jet-setting, hard-charging banker who fine-tunes his image — sending a message to staff last year to ditch the middle initial “M” in references to him. He still uses the DMS moniker for his private LLCs.

In June, Solomon posted a photo of himself from inside the London Tube, praising public transit while wearing his signature wide-lapel blazer with five buttons on each cuff. Not shown was his ensuing weekend getaway to the South of France on the company plane.

Waldron, on the other hand, has stuck to John E. Waldron on Goldman paperwork. The father of six and part-time hockey coach brags about having double dinners — PB&J sandwiches with his kids, followed by steak tartare with corporate CEOs.

“I find him smart, low key, has humility and is not flashy,” said Stan Druckenmiller, the renowned macro investor.

One senior executive praised Waldron’s zeal for pursuing business. If you tell him there’s $12 of extra revenue in a suburb in northwestern Pennsylvania, he will jump in an SUV and go, the executive quipped. He said he much prefers Waldron the client-facing Goldman president to Waldron the in-the-weeds COO.

As Solomon faces more heat, the risk for Waldron is the alarming pace at which the Goldman-verse is floating alternatives not named Waldron. While some are bogeymen, at least some are plausible. None of them would have merited serious discussion just two years ago.

Senior Wall Street executives frequently find themselves at a place where they have to pick a side, according to Jeanne Branthover, who works on succession with companies and has seen many instances when plans go awry.

“Some people would choose loyalty over ambition,” she said. “But I think many people would choose ambition over loyalty.”

— With Max Abelson

Follow all new stories by Sridhar Natarajan

Follow all new stories by Sonali Basak

In this Article

332.21USD

–1.64%

30.43USD

–3.00%

672.82USD

–2.90%

Have a confidential tip for our reporters? Get in TouchBefore it’s here, it’s on the Bloomberg Terminal