Signaling as a Service

Length: • 12 mins

Annotated by Ömer Uzun

01 Intro

One of the best books I have read in the last few years is The Elephant in the Brain by Robin Hanson and Kevin Simler.

The book makes two main arguments:

a) Most of our everyday actions can be traced back to some form of signaling or status seeking

b) Our brains deliberately hide this fact from us and others (self deception)

So we think and say that we do something for a specific reason, but in reality, there’s a hidden, selfish motive: to show off and increase our social status.

You may have heard about a similar concept before called conspicuous consumption. Conspicuous consumption describes the practice of purchasing luxury goods (or services) for the sake of signaling the buyer’s wealth in order to attain or maintain a certain social status.

A classic example of this would be a luxury watch: A Rolex isn’t better at telling the time than a cheap Casio – but a Rolex signals something about its owner’s economic power and thus their social standing.

This is not a new theory, but Simler and Hanson argue that a lot more human behavior can be explained by signaling. Here are a few examples from the book:

- Consumption

Signaling does not only explain luxury purchases but also consumption of all sorts of other goods: “Green products” are more about signaling a prosocial attitude than actually helping the environment. Other consumption signals include loyalty to a specific subculture (e.g. band t-shirts), athleticism & health consciousness (athleisure clothing) or intelligence (e.g. Rubik’s Cube). - Charity

There are several indicators that suggest that giving to charity isn’t really about improving the well-being of others: The lack of effective altruism demonstrates that we don’t care much about the actual outcome of our donations and studies show that our charitable behavior is heavily driven by visibility (hardly any donations are anonymous), peer pressure (95% of donations are solicited) and mating motives (donations are higher and more likely when observed by a member of the opposite sex). Charity is about appearing generous rather than actually doing good. - Education

You would think that going to school is about learning and acquiring skills, but then why do students pay tens of thousands of dollars for Ivy League schools when all of the learning material is effectively available online for free? Why do we use grading systems when we know that students learn worse when being graded? The answer, again, is signaling: Education helps with credentialing and signaling to potential employers.

There are many more examples in the book (and I recommend reading the whole thing), the point the authors are trying to make is clear: Almost everything has a signaling component – we are just not aware of it. In fact, Hanson believes that “well over 90 percent” of human behavior can be explained by signaling.

Whether or not you agree with that exact number, I think it’s an interesting thought experiment to look at a specific behavior and think about what the hidden signaling subtext of that behavior might be.

Ever since finishing the book, the signaling behavior I’ve been thinking about the most is the adoption – and more importantly the monetization – of software products and services.

This is what this blog post is about.

02 Components of Signaling

Let’s take a closer look at signaling first.

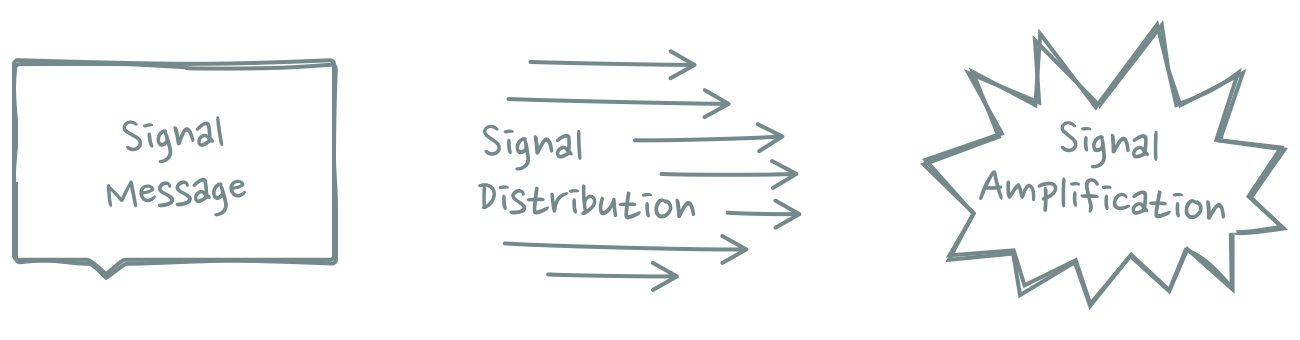

The way I see it, signaling can be broken down into different components:

- Signal Message

- Signal Distribution

- Signal Amplification

To better illustrate what I mean let’s take a pair of sneakers as an example.

The first component is what I call the signal message. This is whatever (hidden) subtext you are trying to convey. In the case of our sneakers this is probably something along the lines of “I can afford to spend $100 on a pair of shoes” and “I live an active, healthy lifestyle”.

In order to get your signal message across to other people you need some form of signal distribution. This is the second component of my signaling taxonomy.

So how are you going to distribute the signal message of your sneakers? You simply wear them where other people can see them. The obvious constraint here is that your signal distribution is limited to things you can display in public. This is why people are willing to spend hundreds of dollars on shoes but not on socks.

The third component is signal amplification: If everyone is wearing cool sneakers .. how do you make sure yours stand out? You could buy the pair with the most noticeable design or the one with the flashiest colors, for example. These signal amplifiers help you to better compete against status rivals.

Let’s recap: Signaling can be broken down into signal message, distribution and amplification. “Real world” products are great at visualising a signal message due to their physical nature. However, as a consequence there are also physical boundaries to distribution because there are only so many people you can signal to at once.

But what about software?

03 Software’s Signaling Limitations

Digital products have one crucial disadvantage over atom-based products and services: Intangibility. Apps live on your phone or computer. No one can see them except for you.

The signal message of a fitness app is the same as that of a gym membership or athletic wear (strength & fitness display), but the signal is much weaker because you can’t distribute it to anyone.

I believe that this is the main reason why consumer software companies have a harder time monetizing than their physical counterparts.

Here’s another example: eBooks have never caught up with paper books despite being more convenient. On the contrary, physical book sales have remained stable (and in some markets even increased) in recent years. Interestingly though, people spend less time reading them. Their value seems to stem from lying around the house to impress visitors (see also coffee table books) – a benefit digital books simply can’t offer.

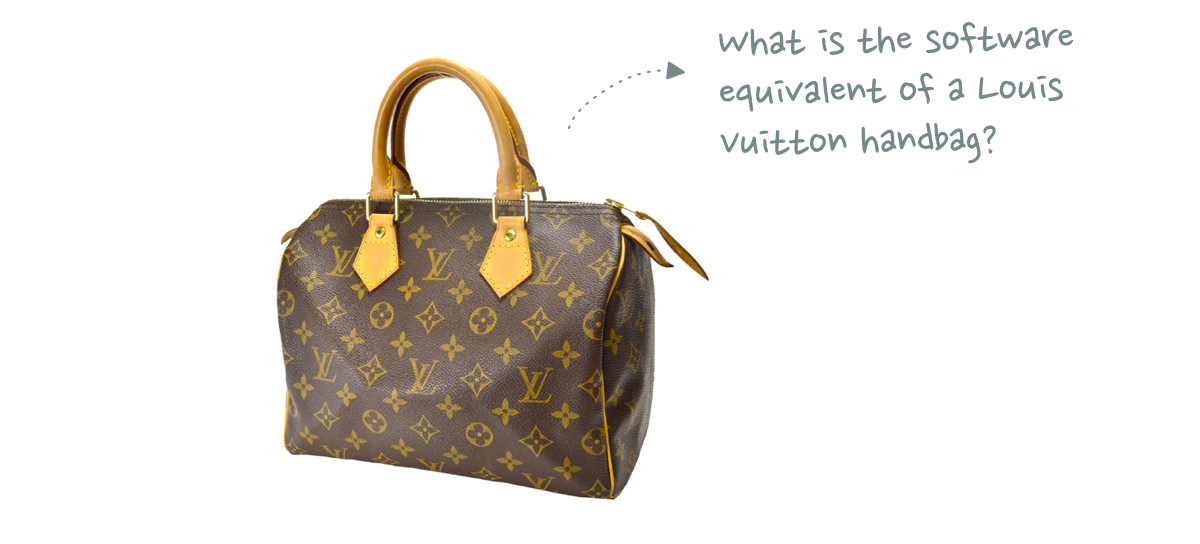

Another point of evidence is the lack of luxury software products. People spend absurd amounts of money on jewellery, handbags and cars, but I can’t think of a piece of software with an even remotely similar price tag. Sure, people have tried to sell $999 apps but those never took off.

The app that comes closest to a luxury service that I can think of is Superhuman, which charges its users $30 a month for an email client (which you could also get for free by just using Gmail).

But there’s a difference to other software products: Superhuman has signal distribution built in. Every time you send an email via Superhuman, your recipient will notice a little “Sent via Superhuman” in your signature.

In a similar fashion, apps like Strava use their built in social networks as a signal distribution channel for their premium subscriptions. Users who have upgraded get a little premium badge and appear in exclusive premium leaderboards.

Another interesting way to solve the signal distribution problem is to add a physical product to a software’s premium offering, which allows signaling via casual contact (like fashion products).

Neobanks such as N26 or Revolut reward their premium users with a fancy metal card which doesn’t just look nice but is also noticeably heavier than normal credit cards. There aren’t a lot of other benefits that justify the hefty €17/month price tag these banks charge for their premium tiers – clear evidence that the primary monetization driver is in fact signaling.

04 Signal Distribution as a Service

While many digital products struggle to monetize as well as their real-word counterparts, the Internet has created a whole new kind of signaling utility: Distribution as a service.

Physical products are limited to the amount of people you see in public – but the Internet allows you to reach a virtually infinite number of people at once.

This is the primary value that social networks like Facebook, Snapchat and Instagram provide. These services don’t contain a hidden signal message. All they do is provide signal distribution at scale. Want to increase the number of people who can see your sneakers? Just take a photo and post it on Instagram.

A positive feedback loop of views, likes and comments helps you to quantify how successful your signal distribution has been.

Eugene Wei calls this Status as a Service:

By merging all updates from all the accounts you followed into a single continuous surface and having that serve as the default screen, Facebook News Feed simultaneously increased the efficiency of distribution of new posts and pitted all such posts against each other in what was effectively a single giant attention arena, complete with live updating scoreboards on each post. It was as if the panopticon inverted itself overnight, as if a giant spotlight turned on and suddenly all of us performing on Facebook for approval realized we were all in the same auditorium, on one large, connected infinite stage, singing karaoke to the same audience at the same time.

It’s difficult to overstate what a momentous sea change it was for hundreds of millions, and eventually billions, of humans who had grown up competing for status in small tribes, to suddenly be dropped into a talent show competing against EVERY PERSON THEY HAD EVER MET.

Social networks are subject to network effects: The more users join a network, the more valuable the network becomes. Your incentive to use Facebook increases with the number of people you can distribute your signal message to. This is why social networks are free to use – in order to maximize their signaling potential they need to acquire as many users as possible.

A social network like Path attempted to limit your social graph size to the Dunbar number, capping your social capital accumulation potential and capping the distribution of your posts. The exchange, they hoped, was some greater transparency, more genuine self-expression. The anti-Facebook. Unfortunately, as social capital theory might predict, Path did indeed succeed in becoming the anti-Facebook: a network without enough users. Some businesses work best at scale, and if you believe that people want to accumulate social capital as efficiently as possible, putting a bound on how much they can earn is a challenging business model, as dark as that may be.

While Path did indeed fail as a distribution provider, I would argue that keeping the network’s size small can still have benefits in line with my signaling theory: Deliberately limiting the number of people who can join a network (e.g. by charging a membership fee) creates scarcity which in turns makes the network more interesting. Network membership becomes the signal message. Users pay a membership fee to signal to other members that they are part of the tribe.

Some examples:

These social networks still rely on some critical mass and network effects, but need to set an artificial limit to the amount of people who can join. If membership isn’t scarce, the membership loses its signal message. The same applies to physical products: Apple will never offer a cheap iPhone to compete with low-end Android devices – it would destroy the company’s signal message that the iPhone is a luxury product.

In contrast to iPhones, there is another limitation that social networks with this strategy face: Like in the before mentioned software examples, signal distribution is limited to the in-group. Signaling however is strongest when you can signal tribe affiliation to both in-group members as well as outsiders. This is also the reason why luxury car manufacturers don’t limit their advertising campaigns to potential buyers but deliberately extend it to people who will never be able to afford the car.

But as we’ve discussed earlier, the intangibility of software makes signaling to the out-group difficult: You would instagram a photo from your Equinox gym, but would you share a screenshot of your MyFitnessPal Premium subscription?

Instead of monetizing network membership, the software products that monetize most successfully have chosen another strategy: Make memberships free and monetize signal amplification instead.

05 Monetizing Signal Amplification

Earlier, we defined signal amplification as product features that help users to increase the strength of the signals they want to convey to stand out of the crowd. In the example of our aforementioned sneakers, flashy colors help to amplify our signal message.

Similar amplifiers exist in the software world, but they often come in the form of a set of tools. Take the Instagram photo editor for example: Applying filters to your photos makes them look nicer and hopefully more noticeable in the app’s status arena – aka the newsfeed.

Eugene Wei calls these amplifiers Proof of Work:

Almost every social network of note had an early signature proof of work hurdle. For Facebook it was posting some witty text-based status update. For Instagram, it was posting an interesting square photo. For Vine, an entertaining 6-second video. For Twitter, it was writing an amusing bit of text of 140 characters or fewer. Pinterest? Pinning a compelling photo. You can likely derive the proof of work for other networks like Quora and Reddit and Twitch and so on. Successful social networks don’t pose trick questions at the start, it’s usually clear what they want from you.

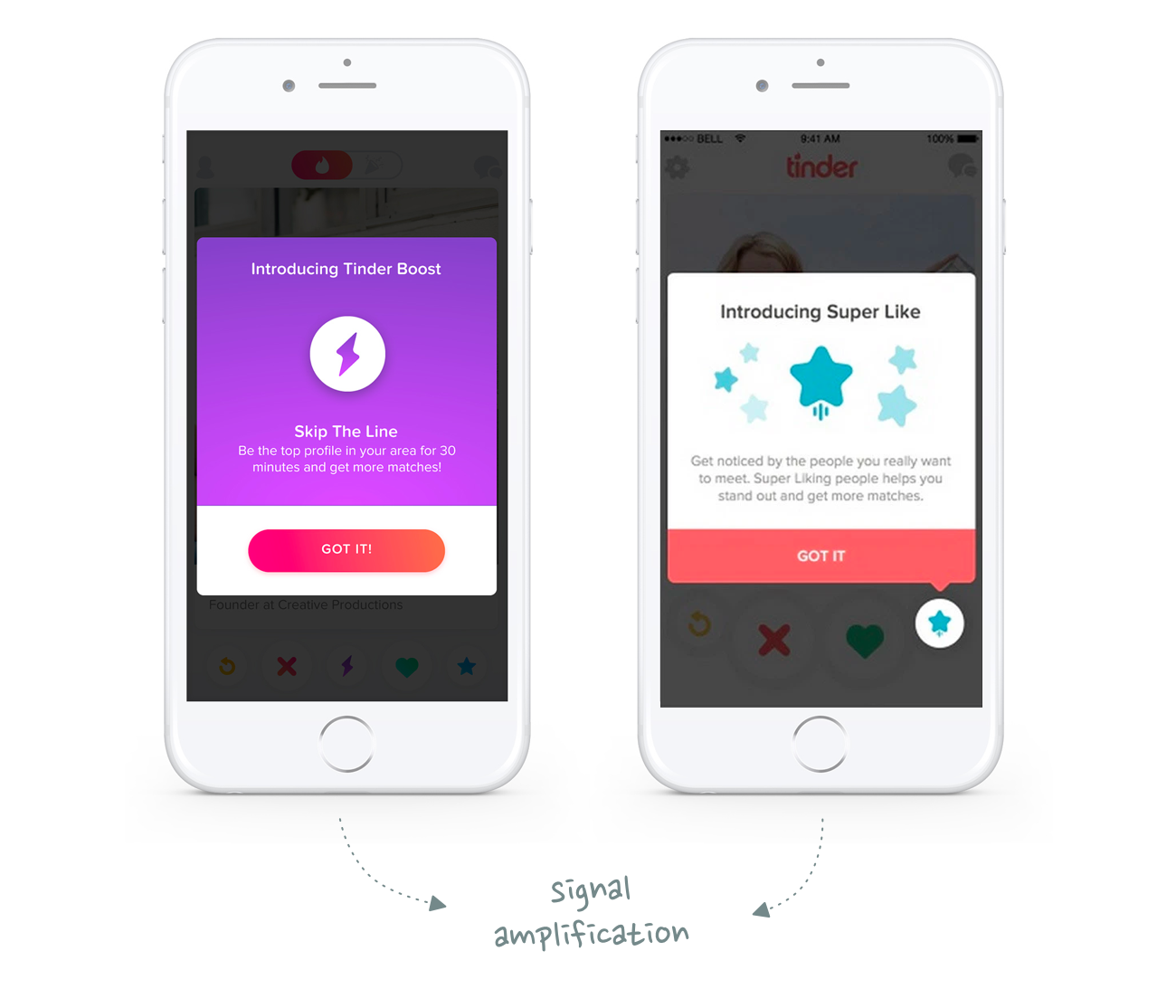

While Instagram, Twitter and the other above-mentioned social networks are free to use, other companies have figured out a clever way to monetize their signal amplifiers. The two companies who have done this most successfully are Tinder and Fortnite.

Let’s start with Tinder.

06 How Tinder Monetizes Signal Amplification

Tinder is a social network for dating – or in other words, a signal distribution network to display your mating worthiness. Like other social networks, Tinder is subject to network effects: The value of the network increases with its size. The obvious strategy therefore is to make memberships free so that as many people as possible can join. (Technically, dating apps are two-sided networks. The value for female members increases with the number of male members and vice versa.)

Tinder’s primary proof-of-work mechanism is to optimize one’s profile picture for a maximum number of swipe rights. But with millions of rivals on the same platform, competing for status with just a few pixels of profile picture real estate becomes a really hard task.

Luckily, Tinder offers a variety of additional signal amplifiers that help you to stand out. The sole purpose of features like Tinder Boost and Super Likes is to outcompete status rivals by giving you preferential signaling treatment. And guess what – they come with a price tag.

Tinder’s entire business model is built on the assumption that people are willing to spend money on signaling. That assumption seems to be correct: Tinder made a staggering $1.2 billion in revenue last year making it one of the most successful apps world wide.

07 Fortnite – The Ultimate Status Battleground

Fortnite has seen even greater levels of financial success: In the last two years combined, the game has brought in more than $4 billion in revenue – and like Tinder, it too monetizes primarily with signal amplification.

For the longest time, the monetization model of games used to be – and for many still is – one-time upfront payments which then allowed you to play the game for as long as you wanted to.

That business model changed with the emergence of mobile games on iOS and Android. Instead of charging players upfront for access, mobile games are typically free to play. However, in order to progress faster and win the game, users will eventually have to pay for small upgrades with in-app purchases.

Similar to these traditional mobile games, Fortnite is also free to play. As a multiplayer game that many play with their real-life friends, this strategy makes a lot of sense – the network becomes more valuable the more people join.

In contrast to mobile games however, Fortnite is also free to win. None of the in-app purchases available impact the core gameplay. You can’t buy more powerful weapons or stronger armor that give you an advantage over other players.

That’s because the core gameplay isn’t the core signaling layer – and thus also doesn’t offer the greatest monetization potential.

Fortnite is more than just a game. It’s more like a giant virtual theme park, or the closest thing we have to a metaverse even. People don’t just come for the battle royale game – they come to meet and hangout with friends.

But if The Elephant in the Brain has taught us anything it’s that you don’t just meet people for fun. You are engaging in a constant battle for attention and status. Signaling is the meta game that Fortnite provides – and monetizes.

Fortnite’s monetization model is based on cosmetics: The skin your character wears; the looks of your glider and the tools you use; the way your character dances (emotes) – all of these are signaling amplifiers with different signal messages to uniquely express yourself in the game. And you have to purchase them.

Fortnite has pulled off what so many other software products have been struggling with – monetizing a purely digital product whose value is not based on utility or entertainment but solely on the one thing we all secretly care so much about: Signaling.

08 Summary

While the physical nature of material goods and services is perfect to visualize hidden signaling messages, there are natural limitations to distribution and amplification.

Software perfectly complements physical goods by distributing their signal messages at scale. Maximizing scale, however, prevents it from monetizing said distribution. This is why social media services are free to use. The added signaling value is solely captured by the physical products that are being shared.

The intangibility and fungibility of software also makes it difficult to create and share (and monetize) software products that contain hidden signal messages of their own. This explains why there are no software equivalents of luxury products such as Rolex watches or Louis Vuitton handbags.

The financially most lucrative strategy for software companies is to provide distribution for free and instead monetize users who want to stand out of the crowd with paid signal amplification.

A closing thought: I tell myself that I write these blog posts “just for fun”, but let’s be honest ... all I really want is to signal how smart I am. So if you could head over to Twitter and give me a Like or a Follow, that’d be great. Thanks!

Thanks to Gonz Sanchez, Jan König, Max Cutler and Robin Dechant for reading drafts of this post.