What jury duty taught me about product management What jury duty taught me about product management

Length: • 8 mins

Annotated by omar

Some content could not be imported from the original document. View content ↗

Unexpected parallels and hidden lessons about leadership and product management from my experience on a jury

Apr 25, 2023

∙ Paid

👋 Hey, I’m Lenny and welcome to a 🔒 subscriber-only edition 🔒 of my weekly newsletter. Each week I tackle reader questions about building product, driving growth, and accelerating your career.

So, I had jury duty last week. Like everyone ever, I expected to get dismissed at some point in the process—until I was juror #1 on a weeklong criminal case.

The experience was equal parts disruptive, rewarding, and fascinating. Being the product nerd that I am (and because we had a lot of time to sit around and think), I started to notice parallels and hidden lessons about leadership and product management. Trials, I realized, are a great lens for studying important soft skills. In both litigation and PM, you’re trying to convince a group of people to do what you believe needs to be done. And facing decades in prison is much higher-stakes than getting button copy wrong 😵💫

Here are five lessons I took away from my jury duty experience:

1. Be super-selective about who’s in the room

The trial lasted a total of three days, including one whole day for jury selection. A third of the trial was picking the jury!

Think about all the time attorneys put into laying out their case, interviewing witnesses, cross-examining witnesses, opening and closing statements, etc. The prosecution and the defense spent as much time picking who they were pitching as doing the actual pitching. I know this timeline isn’t the case for every trial, but from my research, it’s typical.

What’s the product lesson?

- Projects: Think carefully about who you want on your next team. Who’s going to help you align, make decisions, and ship—and who’s going to derail everything?

- Meetings: Think carefully about who you want in that upcoming meeting. Who’s going to help you get to the outcome you want—and who’s going to create confusion?

- Leadership team: Think carefully about who needs to be on your leadership team. Who’ll do real work and push the team forward, and who just wants to be involved?

- Success criteria: Think carefully about how success will be judged for your project. How could you set your team up for success before you even start the project?

- Career: Think carefully about who you want to spend your days with. Is the place you work full of people who are better than you, or do you constantly need to pull everyone along?

2. Tell them what you’ll tell them → tell them → tell them what you told them

Here’s how a trial unfolds:

- Jury selection.

- Opening statements by the prosecution and the defense, each laying out what you’ll hear during the trial. ←(Unexpectedly important)

- The prosecution makes its case by bringing up witnesses and asking them questions to lay out the facts as they see them.

- The defense makes its case by bringing up its own witnesses and asking them questions to lay out additional facts and dispute the prosecution’s facts.

- Closing arguments from each side.

- The jury deliberates and shares their verdict.

What surprised me most was how impactful the opening arguments were on my mindset throughout the trial. Each side started by telling us exactly what their case was going to be—including who we’d hear from, what each person would tell us, and what evidence we’d see. There was no mystery. As a result, as the prosecution (who went first) laid out their case, I always had in the back of my mind, “This sounds damn convincing, but I know the defense will have someone later tell me this wasn’t how it happened at all.” Knowing the key points up front helped me avoid jumping to conclusions too early.

What’s the product lesson? The effectiveness of this simple presentation flow when trying to make an argument to an executive:

- Tell them what you’ll tell them.

- Tell them.

- Tell them what you told them.

This framework is often referred to as the Aristotelian triptych (though it’s not clear whether it actually came from Aristotle), and it connects nicely with the Minto pyramid principle, which teaches us to start a presentation with your conclusion, instead of saving it for the end.

Here’s Daymond John (from Shark Tank) sharing this lesson in 30 seconds—using the actual technique within the video:

3. Don’t go into important meetings not knowing what key stakeholders will say

Most people imagine a trial going like this:

When they’re really mostly like this:

Trials are very low-drama for one simple reason: lawyers are taught never to ask a question they don’t already know the answer to. To accomplish this, they spend a lot of time behind the scenes, pre-trial, deposing witnesses, doing research, and preparing. Most of the work they do to win their case happens before the trial even begins.

What’s the product lesson? Don’t go into important decision meetings not knowing how key stakeholders will feel. Meetings should be low-drama and full of non-surprises. To accomplish this, do the pre-work:

- The meetings before the meeting: Schedule 15-minute pre-meetings with key stakeholders ahead of the meeting, to convince them of your case, and if nothing else, to get a sense of where they stand.

- Get alignment outside of a high-pressure room: Aim for one-on-one low-stakes discussions vs. letting one loudmouth sway everyone.

- Think like a Jedi: Be less Tom Cruise, passionately arguing your case, and more Obi-Wan, pulling strings behind the scenes.

4. Hunt for misalignment, and quickly push everyone back into alignment

Although attorneys try to avoid surprises, surprises do happen. Particularly in cross-examination, when the other side tries to create doubt in a witness’s testimony.

In my trial, the case revolved around a DUI—specifically, whether the defendant drank before he left a party (because the breathalyzer results weren’t conclusive). The defense brought up a witness who was at this party, who claimed he never saw the defendant drink. This witness even told a story of offering the defendant a drink that he declined, because he said he was a designated driver that night and wasn’t drinking. If true, this would create a big problem for the prosecution, whose case rested on the fact that the defendant drank heavily at the party. A serious misalignment for his case!

So what did the prosecuting attorney do? He looked for ways to bring the jury back into alignment (with his story). He drilled into where the witness was throughout the party, and whether he always had eyes on the defendant. It turned out the witness was upstairs for some meaningful period of time making out with his girlfriend 🤣

What’s the product lesson? An important habit of highly effective product managers is to be endlessly hunting for misalignment—and quickly pushing everyone back into alignment. For example, rooting out misalignment between designers and engineers, researchers and PMs, and executives and the team. It’s some of the highest-leverage work you can do.

Some ways to build this habit:

- When reviewing new designs, always bring people back to “What problem are we trying to solve here?”

- When you get a hint that team members are misaligned (e.g. quoting data not everyone has seen, optimizing for different goals, shifting priorities), just say, “We may be misaligned on this. What’s your understanding of X?”

- Create, and keep coming back to, a source-of-truth document that crystallizes the goal, the succinct problem being solved, key assumptions, and key decisions.

- Listen carefully in standups for anything that sounds like misalignment, and ask questions.

- Revisit priorities, plans, and assumptions with your manager in 1:1’s.

5. Influence = evidence + trust

A trial really boils down to which side is better able to influence you. It’s maybe the purest display of influence—with real stakes.

In our deliberation process, before we actually headed into deliberation, the judge specifically gave us instructions to base our decision solely on:

- Evidence (e.g. a mark on a car)

- Expert testimony (e.g. from a breathalyzer technician)

- Witnesses’ firsthand accounts, and how much we trusted them

She told us to ignore:

- What the attorneys told us happened

- Speculation or hearsay from witnesses

- Our own sympathy, or emotion, for the victim or defendant

- What we believe the judge thinks, based on how she interacts with both sides

Essentially, we were told to focus on just the evidence and how much we trusted people. As one example of this in action, the defense attorney was not...great. The judge kept getting angry with him, he kept making mistakes with simple procedures, and he kind of annoyed everyone. But he won. His witnesses were trustworthy, and the evidence we did have pointed us to an acquittal. Many of us joked about how bad the defense attorney was, but that didn’t impact our conclusion.

What’s the product lesson? I previously wrote a post on how to improve your influence, and looking through it again in relation to this trial experience, I’m reminded of how much of your ability to influence others really boils down to two things: (1) how convincing your evidence is and (2) how much people trust you, your evidence, and others on your side. If you’re having a hard time influencing someone, instead of assuming they have something against you, double down on evidence and trust.

Other parallels and lessons that I didn’t have time to explore because jury duty f’d my week

- Getting a jury summons letter in the mail = Getting an invite to a meeting you didn’t want to be in

- The amount of resources spent on small crime = This meeting should have been an email

- The judge setting expectations that she wants the jury deliberation by end of the week = Great example of timeboxing

- Getting dismissed = An upcoming meeting getting canceled

- Proving something beyond a reasonable doubt = Statistical significance

- Hoping they don’t call your name when they’re calling out potential jurors = Hoping they don’t call on you in a big meeting

- Random jurors deciding your fate = An uninformed exec making the call on your project’s future

- Decision by consensus = 😵💫

Finally, I’ll leave you with this clip from a new reality show called Jury Duty:

Some content could not be imported from the original document. View content ↗

Have a fulfilling and productive week 🙏

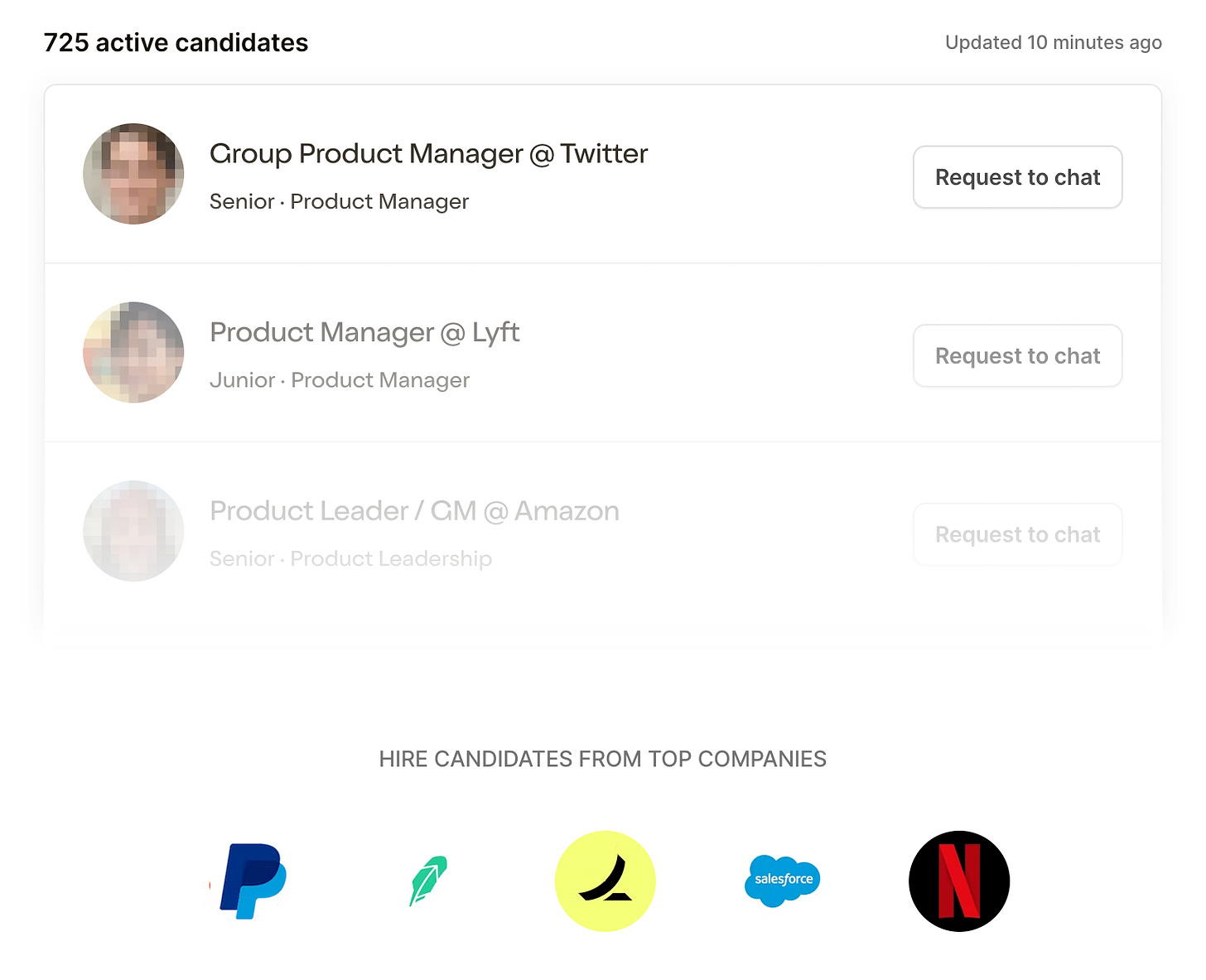

📣 Join Lenny’s Talent Collective 📣

If you’re hiring, join Lenny’s Talent Collective to start getting weekly drops of world-class product and growth people who are passively open to new opportunities. I hand-review every application, and accept less than 10% of candidates who apply.

If you’re looking for a new gig, apply to join! You’ll get personalized opportunities from hand-selected companies. You can join anonymously, hide yourself from companies, and leave anytime.

🔥 Featured job opportunities

- Fitmate Coach: Product Leader (Menlo Park, CA, or remote)

- Wingspan: Product Marketing Manager (NY, remote)

- Wingspan: Senior Software Engineer (Remote)

- Wingspan: Technical Account Manager (Remote)

🧠 Inspiration for the week ahead

- Read: Five big trends that have changed in the last few years by Noah Smith

- Watch: Michael Jackson on Fire Diorama via Tim Ferriss

- Read: The Difficulty Ratio by David Sacks

If you’re finding this newsletter valuable, share it with a friend, and consider subscribing if you haven’t already. Check out group discounts and gift options.

Sincerely,

Lenny 👋