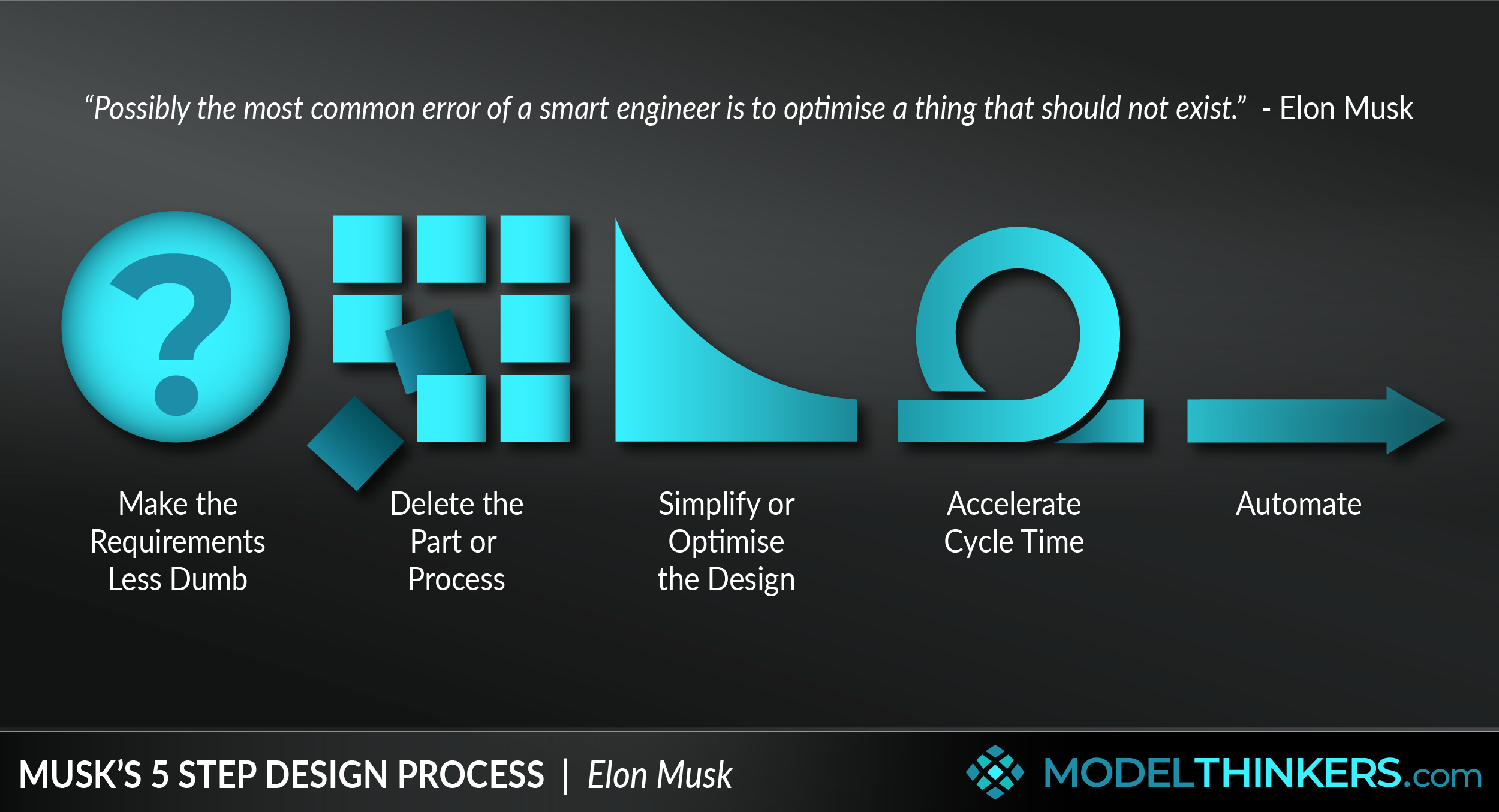

Musk's 5 Step Design Process

Length: • 3 mins

Annotated by Reed Wise

Reed Wise: Elon Musk revealed his 5 Step Design Process that his company, SpaceX, uses to design, build, and launch a rocket into space. The steps are: making the requirements less dumb; deleting the part or process; simplifying and optimizing the design; accelerating cycle time; and automating. This approach is based on challenging assumptions, questioning the question, and rejecting the idea of including more and more features 'in case'. It is reminiscent of Occam's Razor, Lean Startup, and Minimum Viable Product.

How do you design, build and launch a rocket into space in a radically different way from past attempts? That’s the question that faced Elon Musk’s SpaceX, and he recently revealed the process he has embedded into the organisation to make it possible.

Musk’s 5 Step Design Process consists of making the requirements less dumb; delete the part or process; simplify and optimise the design; accelerate cycle time; and automate.

THE 5 STEPS.

This model was revealed by Musk in an interview after he was asked whether the grid fins of his latest rocket design fold in (see the Origins below for the full interview with Everyday Astronaut).

Musk explained that they didn’t, but then expanded by outlining the 5 step process SpaceX was aiming to “apply rigorously”, and which led to the grid fin decision. See the Origins tab below for the original video interview and view the following points for each step in more detail:

- Make the requirements less dumb.

Musk notes that “your requirements are definitely dumb, it does not matter who gave them to you.” Similar to Framestorming and its reminder to ‘question the question’, Musk uses this step to test assumptions, pointing out that requirements from a ‘smart person’ are often the most dangerous since you might not question them enough.

- Delete the part or process.

“If you’re not adding things back in at least 10% of the time, you’re clearly not deleting enough.” Musk suggests starting lean and building up when and if required, but warns that the bias will be to add things ‘in case’, “but you can make ‘in case’ arguments for so many things.” He goes further, arguing that each requirement or constraint must be accountable to a person, not a department, because you can ask that person about its relevance and purpose, rather than having a requirement that nobody owns and persists for years despite being redundant.

- Simplify or optimise the design.

“Possibly the most common error of a smart engineer is to optimise a thing that should not exist,” Musk explains, emphasising the importance of working through the first two steps before trying to optimise. To do this effectively, Musk argues that each engineer needs to take a holistic view of the project, pointing to previous mistakes where engineers had invested enormous resources into reducing the weight of the rocket’s engine but hadn’t adequately addressed the equivalent problem of reducing payload weight.

- Accelerate cycle time.

Musk embraces the drive to go faster but warns against pointing your efforts in the wrong direction, saying “if you’re digging your grave, don’t dig faster.” He seems to recommend an accelerated Agile approach, but only after the first three steps of his process are satisfied to ensure that you’re moving faster in the right direction.

- Automate.

Musk warns against automating before the earlier points are addressed. He relates the story of streamlining a robotic process to build battery mats in the Tesla Model 3. He describes investing massive time and effort to automate and streamline that problematic process before he finally asked what the mat was for. He discovered that it had been created to reduce sound but was no longer required.

IN YOUR LATTICEWORK.

Musk’s design process stems from an engineering perspective to streamline and rethink rocket design but can be applied to almost any design project from UX, a marketing campaign, or product design more broadly.

Elements of Musk's process reflect his championing of First Principle Thinking, and consistently challenging assumptions. We’ve already identified links with Framestorming, and the idea of questioning the question, and his approach is also reminiscent of Occam’s Razor.

The rejection of including more and more features ‘in case’ counters the Redundancy/ Margin of Error model, and Musk’s approach of building ‘good enough’ is very aligned to Lean Startup and Minimum Viable Product, in fact he refers to a ‘Minimum Viable Rocket’ in the interview.

Some content could not be imported from the original document. View content ↗