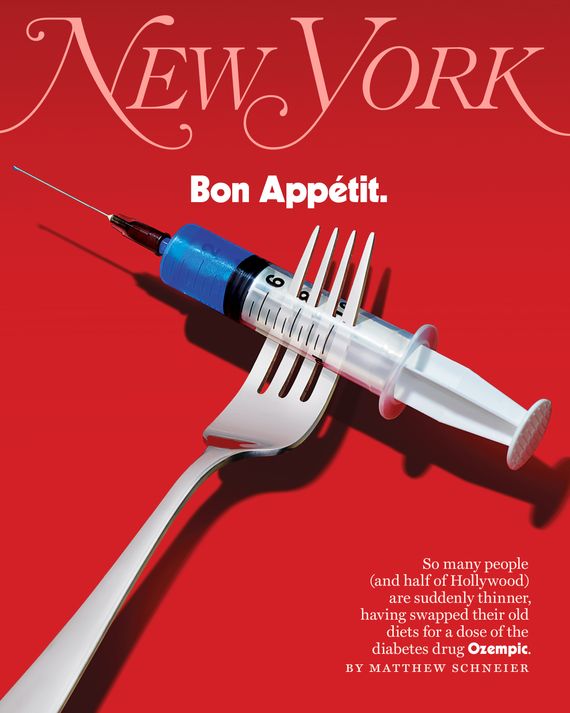

Life After Food?

Length: • 19 mins

Annotated by Mark Isero

Allison is an actress. When we meet up for coffee — she has an almond-milk cortado — in midtown, something’s different about her, but I’m not sure what. She looks like an Instagram version of herself but in real life.

It turns out she’s down about ten pounds and happy about it. “Somebody once told me I had a size-zero personality, and they assumed that I was thinner than I was,” she tells me. “We don’t talk about it, but everybody knows it. Thin is power.”

Allison isn’t alone in seeming to be suddenly, unaccountably slimmer of late. She admitted to me — with the provision that I not use her real name — the reason, one that is increasingly common if still not quite openly discussed. For the past month, she’s been jabbing herself every week with Ozempic, the heavily advertised (“Oh, oh, oh, Ozempic,” to the tune, none too subtly, of the ’70s classic-rock hit “Magic”) diabetes miracle drug, which works by mimicking a naturally occurring hormone, GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide one), to manage hunger and slow stomach emptying.

For diabetics, it lowers blood-sugar levels. It also subdues the imp of appetite. The pounds fly off. That’s why Allison, who is not diabetic, prediabetic, or even overweight, is on it. Doctors have wide latitude to prescribe drugs off label for anyone they think may medically benefit, and many patients have found doctors — or, failing that, nurse practitioners or medi-spas — ready to certify that they would. Or some, like Allison, find it through a peddler not particular about a prescription or in the web’s dark morass.

To get hers, Allison calls up a Los Angeles–based provider she has never seen or met, sends over $625, and is shipped a monthly supply. What she calls Ozempic is not the brand-name product pre-packaged in a sky-blue injector pen by Novo Nordisk, the Danish pharmaceutical company that makes and markets the drug. She receives generic semaglutide, the active ingredient in the medication, and has to mix and prepare it for injection herself, which — since semaglutide is under patent by Novo Nordisk until 2032 in the U.S. — suggests her meds are likely coming from a compounding pharmacy or a vendor selling research-grade ingredients. The lower price is also a tell: Ozempic retails for about $900 a month if your insurance doesn’t cover it.

There are side effects for many Ozempians. Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation are the most common. “I heard somebody say all the gays at CAA are on it and they’re all shitting their brains out,” Allison says. “But no, that wasn’t my experience. It’s kind of like being on a very low dosage of Adderall without that crack feeling.” She’s adjusted. “There have definitely been moments early on where I felt side effects of fatigue,” she says. “But they were temporary, and as my dose has gone up, I’ve been feeling the benefits more.”

She’s just not as hungry, which makes her not as anxious. During busy periods, when she may not be able to closely monitor or prepare her food and get to the gym daily, the Ozempic takes the nearly full-time job of body maintenance off her mind. Before Ozempic, she’d hole up in her hotel on film shoots, juice-cleansing to fit into her costumes. Now, she says, “you can eat one and a half meals a day and then you’re kind of hungry at night, but it’s not terrible. You can drink some tea with magnesium and maybe take a Xanax and get to sleep.”

The appeal of an effortless, near-instant fix proved irresistible to many, especially in the corridors of fashion and entertainment where looking a certain way is a professional requirement. In September, Variety quoted a “top power broker” who said “half of her call sheet last week was full of friends and clients wanting to discuss the risks of Ozempic.” “I was talking to somebody from a project that I will be promoting, and we both kind of confessed that we were about to start it, both of us knowing the visibility that was to come,” Allison tells me. “We just kind of laughed. And I bet we’re not the only ones.”

Ozempic and its cousin drugs, Wegovy and Mounjaro — all, medically speaking, GLP-1 receptor agonists — are reshaping more than just waistlines. In tweaking appetites, they tweak our whole relationship to food, to bodies, and to ourselves and the psychology that links all three. When she was growing up, Allison says, in “my household, we lived to eat. Food was an excursion, food was a reward, food was everything. You’re eating one meal and talking about what you’re going to eat the next meal. I almost feel like this drug allows me to be casual about food in a way that always felt culturally alien to me. I can just have one bite, or two bites, or three.”

A profound and possibly unprecedented change, in other words, might be taking place. Isn’t appetite, after all, what makes us us, for better or worse? “Subdue your appetites my dears, and you’ve conquered human nature,” as Dickens’s philosophical schoolmaster, Mr. Squeers, told young Nicholas Nickelby. Of course, his mouth was “very full of beef and toast” at the time.

Weren’t we supposed to have moved on from this? The discourse on bodies has changed since the days when a slender figure could be blithely and uncomplicatedly celebrated, sought, or advertised. The days when, as Linda Wells, the founding editor of the beauty magazine Allure, says, “we ran cover lines all the time about ‘How to Lose the Last Five Pounds,’ ‘Diets That Don’t Feel Like Diets.’” Getting-skinnier discussions have become fraught; we profess admiration instead for wellness. Everyone laments the ghouls of body dysmorphia and eating disorders and the pressure social media exerts on teens. No one longs to go back to the days when Lucky Strike could advise, “To keep a slender figure no one can deny, reach for a Lucky instead of a sweet,” or when Louis B. Mayer kept Judy Garland on a diet of chicken soup, black coffee, and amphetamines to stay starlet ready. Ours was supposed to be the feel-good era of Lizzo and Ashley Graham and Adele.

Then Adele lost all that weight.

As did countless other celebrities. A flood of gossipy media coverage followed. Which celebrities are or aren’t on Ozempic became a new blind-item staple. The drug’s breakout moment was the discussion of whether Kim Kardashian used it to fit into Marilyn Monroe’s dress for the 2022 Met Gala. (She denied it.) Only a few admit it openly, as Elon Musk did about using Wegovy. Rumors flew of Hollywood “Ozempic parties,” and there were passionate denunciations by Real Housewives who swore they’ve never touched it. Chelsea Handler attempted to split the difference by claiming, on the Call Her Daddy podcast, that she had been on semaglutide, didn’t realize it was akin to Ozempic, and stopped when she found out. #Ozempic has racked up hundreds of millions of impressions on TikTok. Meghan McCain, the former co-host of The View, wrote an angry op-ed for the Daily Mail about being “urged” to take it to lose her baby weight. (She refused.)

Although it’s been approved and prescribed since 2017, the buy-in of Hollywood, openly or not, took Ozempic from medicine to status symbol. The message that dramatic weight loss is now readily, effortlessly available for those who can afford it spread across text chains and friend groups along with referrals to willing prescribers. Not since Botox, and before that Viagra, has a drug brand become so well known so quickly.

“I heard about it from a client, and when I asked, she was like, ‘You haven’t heard about this? Do you have friends?’” a fashion stylist I know tells me. She raised the topic in one of her group chats, where a doctor pal reported it was safe, effective, and impossible to get in New York because of demand. “That got everybody cooking,” she says. “This was probably in early summer. By the fall, I knew five people on it. And now I feel like everybody’s on it.”

Laila Gohar, whose surreal food sculptures and installations have convinced New Yorkers they need to invest in egg chandeliers, had never heard of Ozempic until a friend called her from California two months ago. “Everyone in L.A. is skinny now,’” he told her. Wasn’t everyone already? she wondered. “Well, the last few people who weren’t,” he said, “now are.”

About a year ago, the contemporary artist Joel Mesler realized that Ozempic was sweeping New York and the art world. “I would come into the city, and every time I would see old friends, they were half the size,” Mesler, who lives in East Hampton, tells me. A friend put him up at the Park Hyatt in midtown for the night, and in exchange, he gifted her a stack of Ozempic-themed drawings on hotel stationery. “That was literally every conversation I had during the day all the way through the evening.”

Now, the drugs are popular everywhere among anyone who’d like to be a little skinnier, whether their careers depend on it or not. At the city’s restaurants, they’re ordering less. “I obviously don’t know when someone is taking drugs,” says Anthony Geich, director of guest relations at Priyanka Chopra’s haute Indian restaurant, Sona, but over the past couple of months, “I’ve definitely noticed the trend of salads being ordered more, or people who are boxing their food up at the end of the night.” Ozempic patients report diminished interest in drinking, too; a glass of wine, tops, one told me. Another said she had to remind herself even to drink water.

Sales figures bear out that the GLP-1 drugs are going gangbusters. Novo Nordisk’s operating profits are up 58 percent since 2017, the year it introduced Ozempic, and sales of the GLP-1 agonists grew 42 percent last year, accounting for 98 percent of the company’s overall growth. According to IQVIA, a health-care data-analytics company, 1.2 million prescriptions for Ozempic were filled nationwide in December 2022, a 64 percent increase from the previous December. And while the company is careful to note that it does not encourage anyone to take Ozempic but diabetics — “As a company, we do not promote, suggest, or encourage in any way off-label use,” says Dr. Jason Brett, executive director of medical affairs for Novo Nordisk — it’s quite clear not just diabetics are getting their hands on them.

Komodo Health, a firm that tracks health-care data for 330 million patient files, notes an uptick in people with no prior record of diabetes receiving these drugs — a fourfold increase in California alone. They’re younger, too: Of all nondiabetic patients who have been prescribed Ozempic or Mounjaro, almost 40 percent are between 25 and 44. (For all patients, the majority are between 45 and 64.) While increases are to be expected when drugs are new to market or undergo label expansions, says Dr. Tabby Khan, Komodo Health’s medical director, “I have never seen this kind of magnitude. I don’t really see a lot of ads for drugs on TikTok or Instagram, but whenever I log on to either of those platforms, I think by virtue of being a woman in her 30s, I am just inundated with information about these drugs.” (Eighty-one percent of prescriptions for these new drugs are written for women.)

At NYU Langone Health’s Weight Management Program, they have eclipsed all the competition. “The last six months, I’ve written 1,400 prescriptions for semaglutide,” says Dr. Holly Lofton, the program’s director. These medications are “hands down the most common prescription since they came out.” Patients ask for them by name, and even the need to inject the medicine, which for previous drugs had scared some off, has taken on an appealing aura. “They come in begging for it,” she says. “If I give them pills, they’re disappointed.”

Let’s be clear: For those who need them — medically rather than cosmetically — the drugs are a godsend. The primary indication for Ozempic and Mounjaro — and the only condition they are currently FDA-approved for — is the treatment of type-2 diabetes (the lifestyle-contingent, typically adult-onset diabetes, as opposed to the congenital, early-onset type-1). Diabetes is an American epidemic; according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 37.3 million adults in the U.S. are diabetic and another 96 million prediabetic. Obesity, an associated chronic disease, affects millions, too.

The basic mechanisms of these drugs are not new. The first GLP-1 drug, exenatide, was approved for diabetes in the U.S. in 2005. It was greeted as a revelation. Improvements came quickly. “There were just gasps” at the American Diabetes Association’s scientific meeting when results for liraglutide, another GLP-1 drug and a forerunner to Ozempic, was announced, says Dr. Robert Gabbay, the organization’s chief scientific and medical officer. “Cheers and some standing ovations. It was dramatic.” But the earlier GLP-1 drugs were shorter acting, requiring more frequent injections and offering much less in the way of weight reduction. Then came Ozempic, soon followed by Wegovy, a higher-dose semaglutide formulation from Novo Nordisk — and the only one of the three actually approved for weight loss — in 2021, and then Mounjaro, from Eli Lilly and Company in 2022.

From a medical perspective, their effectiveness is thrilling, and patients welcomed them with practically religious reverence. Paul Ford, who has always struggled with his appetite, wrote in Wired that “where before my brain had been screaming, screaming, at air-raid volume — there was sudden silence” once he was on one of these drugs. “At an office I observed the stack of candies and treats with no particular interest,” he wrote. “The sin” — gluttony — “is washed away ... Baptism by injection.”

Even off-label, for those who have struggled for years to shed, and then keep off, a few or many pounds, these medications have felt worth whatever sacrifices — ethical, financial, gastrointestinal, or otherwise — that they require. “I have tried every single thing,” says Anna, a New York woman in her early 50s (who, like all the patients interviewed, wasn’t eager to use her real name). Nothing worked — until Mounjaro. The desire to nosh evaporated; emotional eating on Ozempic is a recipe for making yourself sick. “I’m now one of those people who’s just, like, not that hungry,” she says. “And I feel better than everyone.”

No miracle cure is without risk. Dieters of a certain age will remember the fen-phen craze of the ’90s — a drug cocktail of fenfluramine and phentermine — that seemed like a revolution until it turned out fenfluramine caused cardiac-valve damage, leading to death in some patients. Belviq, a more recent addition to the diet-drug pharmacy, was recalled several years after its approval when the FDA determined that the “potential risk of cancer outweighs the benefits.”

In the case of the Ozempic, an FDA warning alerts users to the development of thyroid tumors in rodents, and it can be dangerous for those who have (or have a history of) pancreatitis or a certain type of thyroid cancer. For nondiabetic patients, there might be other issues — or there might not. “The truth is we really don’t know,” says Lofton, the NYU doctor. “We don’t have enough evidence in those people because we never studied it in those people. So we have to find out.”

But given under proper supervision — and in conjunction with diet and exercise, as these drugs are meant to be used — the GLP-1’s are, so far, thought to be safe and well tolerated, at least in those for whom they were intended. “It worries me,” admits Anna (who is not diabetic). “I hope this ends up not being like thalidomide, you know?” (Thalidomide was a 1950s morning-sickness treatment that notoriously caused flipperlike birth defects.) I wonder if that concern would be enough to make her stop taking the drug — though, given that she confessed to driving an hour into Jersey to find a pharmacy that stocked it, I suspect I know the answer already. “If they said it’s an increased chance of lung cancer, I wouldn’t take it,” she says. “I mean, this is so humiliating, but I’m like, Thyroid cancer’s not that bad?”

The bigger worry is not finding it. Since Ozempic, Wegovy, and Mounjaro took off, pharmacies have struggled to keep them on hand and patients have struggled to find them. Lofton says her patients have been emailing frantically, nonstop, and are cutting their doses in half to stretch them out. “Don’t even bother calling,” says Adrienne, a mother and Upper West Sider who was prescribed the drug for her prediabetic condition and shunted from pharmacy to pharmacy in search of it. “They’ll tell you it’s out of stock.”

Even Novo Nordisk seems a little surprised by its own success. “We should have forecasted better,” CEO Lars Fruergaard Jørgensen told The Wall Street Journal late last year by way of apology. The company says it expects continued, if intermittent, supply issues for some dosages through mid-March. Eli Lilly says there may be disruptions and delays of Mounjaro deliveries, too.

In these conditions, even legitimate purveyors have taken on an air of indecency. “My local drugstore just called me and said, ‘We have some’ — it’s a bit like contraband,” says Arthur, who was prescribed Ozempic for diabetes. “People are swarming their doctors, like, ‘Give it to me, give it to me.’”

But for Arthur, a longtime gourmand, getting it has been a relief. “It’s a bit of a pleasure to not be so hooked to this stuff,” he says — meaning food, not Ozempic. “You’re suddenly a normal human being. I don’t need to eat this giant haunch of dead flesh.”

The tension between those who need it — and may not be able to get it — and those who want it but don’t, in the eyes of the larger culture, necessarily need it, is one of the defining qualities of the Ozempic moment. The whole shaky edifice of wellness rested on the rickety foundations of body acceptance: Everyone was beautiful; it was the standards, not the bodies themselves, that were wrong. Which is true, of course — it just turned out we only sublimated the standards, hid them behind vagaries of looking good, feeling good, and being so much more buoyant without dairy, or gluten, or whatever. How quickly we’ve abandoned our contortions and commitments to acceptance as soon as a silver bullet comes around, and how fulfilling some seem to find it to be the thing they swore they’d overcome. Which may be the reason that among those who are winching themselves tighter and tighter, it’s still whispered rather than shouted. If that. “Should anyone suddenly appear svelte, I just assume it’s Ozempic,” says Lauren Santo Domingo, the social fixture and chief brand officer of Moda Operandi. “However, if they elaborate unprompted on their new diet, then I know it’s Ozempic.”

The most dominant body isn’t even the body that walks around with us all day; it’s the one photographed and disseminated. “It’s like everyone is so psychologically damaged from living a two-dimensional life,” Alissa Bennett, who writes and lectures about art and is a director at the Gladstone Gallery, tells me. She’s found herself talking about Ozempic all the time; everyone takes it, and she considers it bizarrely accessible. It’s like Facetune injected into real life. “Do you read the Daily Mail ever?” she asks me. “They’re like, ‘Look at these Photoshop fails!’ and people have waists that have a circumference of four inches. And so when it sort of happened” — that everyone’s real waists were whittled down to skewers, too — “the weird thing is I didn’t really notice it.”

Wells, the former Allure editor, notes a strain of opprobrium that surrounds Ozempic’s use, at least for the skinny interlopers. “It’s kind of an accusation,” she says. “And it’s an accusation that people are denying.” If thin is an unspoken virtue, then part of its virtuousness comes from having worked for it, earned it. “I think everyone’s always been wary of weight loss that isn’t a struggle and a result of hard work and denial.” Ozempic is a diet that’s not a diet, wellness that’s only wellness for the person you’re taking it from, whose ease feels like a cheat. She worries rather than solving the conundrum of what weight is healthy and attractive for you, these drugs merely move the goalposts of acceptably slender. “Now, if you don’t take Ozempic, are you by comparison overweight?” she asks. “I always used to think that when you travel from New York to Los Angeles, you gained ten pounds when you landed because everyone else was so thin. Now what does that mean? Did I just gain 20 pounds?”

It doesn’t help that it’s the kind of women who claim to “never really have to diet” who seem particularly enthralled with the new drug. “Especially for women who have been thin their whole lives — but not skinny, not fashion thin — the idea of touching that without having to sweat is really fun,” my stylist friend says. “It’s really fun for them to have their jeans hang off of them like they’re a Hadid. There is an addictive quality to it.”

They are also the women most susceptible to what Dr. Paul Jarrod Frank, a New York dermatologist, first called “Ozempic face,” meaning the aging effects sudden weight loss can have; Frank specializes in treatments to smooth and contour the newly wrinkled and the use of injectable fillers to replump the newly sunken. (He also offers referrals to planar-face-lift specialists for those who need heavier treatment: “There’s only so much I can do. I’m not going to overfill a balloon.”) “Anyone who thinks they’re gonna take a shot of Ozempic and it’s gonna cure all their problems, then they’ll eat and do whatever they want, those are the people that are gonna be very disappointed in life,” he says. “No matter how skinny you get, you may still have your mother’s outer thighs. That’s where I come into play. We happen to live in a society where people — particularly the top one percent — have greater access to not only the medicines but also the trainers and the nutritionists and the cosmetic dermatologists to try and make all their dreams come true.”

In his offices on Museum Mile and in the West Village, Frank estimates he sees half a dozen patients on “weight-loss journeys” every day, many on Ozempic, Wegovy, or Mounjaro — of whom, he estimates, about half were previously overweight and half “just kind of riding the bandwagon of never too rich, never too thin.”

Those who advocate body positivity, naturally, see an even darker message in the medications or, at the very least, the press coverage around them. It boils down to “Can we finally be rid of fat people?” as Aubrey Gordon, author of “You Just Need to Lose Weight”: And 19 Other Myths About Fat People, put it to Slate’s The Waves podcast. “‘Can we finally stop having fat people around so I don’t have to look at them anymore?’ ... I’m trying to find a way to soften this, and I can’t,” she added. “It feels, like, really morally bankrupt to me to say, ‘It’s more important to me that I look the way I imagined looking in a swimsuit than that you have what you need to stay alive.’”

That sentiment is mostly drowned out by a medical community that sees diabetes and obesity as the bigger problem — and a drug industry that sees them as a bigger opportunity. To hear Novo tell it, its success just indicates that there’s more to be done. “Less than one percent of patients who are eligible for bariatric surgery get it,” says Brett. “I think we’re up to maybe about 2 percent of patients who are eligible for an anti-obesity medication actually get one. So, yes, there’s growth and improvement” in the category, he adds. “But when you look at the scope of the problem and how many people are being treated appropriately, there’s still a lot of room for growth and improvement.”

Novo is in a race for the obesity and weight-management market, the next big prize, and it’s got a good head start: The approval of Wegovy in 2021 was the first for a weight-loss drug since 2014; in less than a year, more physicians were prescribing it than Saxenda, Novo’s previous weight-loss drug — and with 70 percent of America now overweight or clinically obese, the potential profits are huge. The company crowed to investors last year that it hoped to “strengthen obesity leadership and double current sales,” aspiring to surpass $3.5 billion in sales of its obesity products, including Wegovy, by 2025. Just before Christmas, the FDA approved Wegovy for adolescents 12 and older, and just after New Year’s, the American Academy of Pediatricians issued its first clinical guidance on the treatment of chronic obesity, recommending the use of weight-loss drugs in coordination with lifestyle and diet changes (not without pushback from fat-positive activists).

More developments are on the way, and the competition is likely to ramp up. Novo is in phase-three trials of a semaglutide pill for obesity and a new compound medication, known as CagriSema, that pairs semaglutide with another drug and may deliver even more weight loss than its predecessors. The FDA is fast-tracking its investigation into tirzepatide, the active ingredient in Mounjaro, for weight management, though soon enough it may be joined by another Lilly obesity drug, currently in phase one. Amgen is working on a still-unnamed drug in early trials where the sample size is small but the results are encouraging. Pfizer, ERX, and Otsuka all have clinical tests registered with the government in active or recruiting stages. The next three years, says NYU Langone’s Lofton, will be pivotal for obesity medicine: “We have lots of things in the pipeline looking really promising.”

A few months back, April, a school counselor from Detroit, was prescribed Ozempic to manage her diabetes. She’d never even heard of it when her doctor suggested it.

When she came to New York recently for the birthday of her cousin, who works in fashion, he and all his friends noticed a difference immediately. As soon as she strode into Dumbo House wearing a secondhand python-print Roberto Cavalli dress — “I can’t afford brand-new Cavalli,” she says, laughing — she felt noticed, like she stood out. Not easy to do in that room. Later, over drinks, she credited Ozempic. Some of her cousin’s friends inquired as to whether she had any extra to sell: The gays were planning ahead for Fire Island this summer.

“People were asking me, ‘How did you get it? How did you get it?’” she says. “I got it because I’m diabetic. It’s not a recreational drug for me.”

These drugs are all intended for long-term use. In other words, they’re only fixes for however long you take them. Stop taking them and your appetite returns, and the weight usually follows. (“Everyone is suddenly showing up 25 pounds lighter. What happens when they stop taking #Ozempic?????” tweeted Andy Cohen.) A recent study funded by the company acknowledged that cessation of semaglutide treatment led study participants to regain most of the weight they had lost within a year.

April’s side effects have been unpleasant — she was nauseous, occasionally threw up, and had awful headaches. She’s hoping to go off it as soon as she can. Smoothies are the only thing she seems to be able to tolerate, and she misses her favorite foods: pasta Alfredo, Brussels sprouts, strawberry ice cream. “I can’t wait to eat my ice cream again,” she says. But the upside of her ten-pound weight loss — from 172 pounds to 162 — has given her pause. The New Yorkers’ approval boosted her confidence, and when she posted her Cavalli look on Facebook, everyone said she looked fabulous.

“It’s almost like a gift from the curse,” she says. “I don’t want to gain the weight back.”

And so our fraught but fulfilling relationship to the table continues, one that no shot, lifehack, or Soylent can has yet been able to dissolve.

Arthur, the former gourmand, admits that living without appetite, “It’s a bit of a shock.” But he’s come around. “You know what I got for Christmas?” he asks me. “A giant microwave so I can warm up burritos. I’ve become addicted to Japanese sweet potatoes. I like them. They’re fine. I don’t need that fancy shit.”

Surely he misses it? Not really. “The old enjoyment, or dread, or whatever you felt is gone,” he says. But sometimes, he adds, tossing a crumb of concession, if he has a big eating week coming up, something he’s looking forward to, he’ll skip the week’s shot.

“You know, you do miss food a little bit,” Arthur admits. “But not that much.”