It is time for a thread on traditional urbanism, or...

Length: • 10 mins

Annotated by Pepijn

It is time for a thread on traditional urbanism, or town planning 13th century style. I will dispel some myths of modern dis-urbanism.

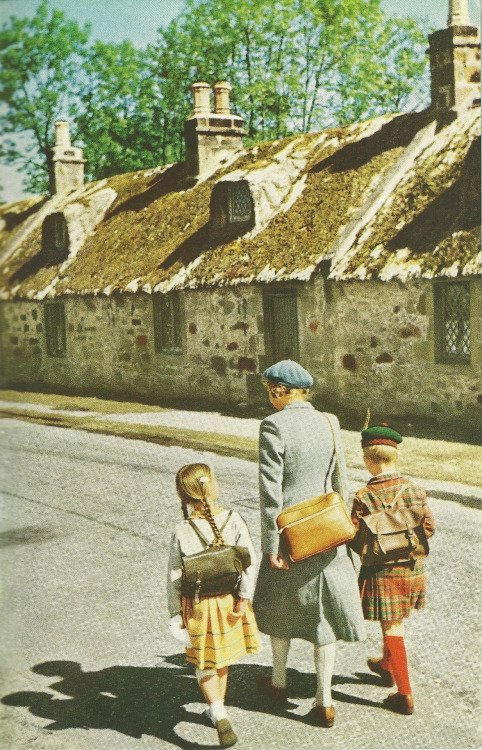

Traditional urbanism has short blocks. No building takes more than 3-4 seconds to walk past, providing interesting colors, shops, textures.

Modern dis-urbanism means massive buildings, long block: takes minutes to walk past with nothing to distract or relieve the tedium. (Zürich)

Traditional towns built with terrain: hills, valleys, stairs, steps, corners, odd squares. Landscaping unnecessary/uneconomical. (Stockholm)

Modern dis-urbanism has buildings/houses separated, apart, at best standing-off across wide streets, making community impossible. (Hamburg)

Traditional urbanism means buildings are tight, close, interlocking and over-looking, often built right into their neighbors. (Colmar)

Traditional urbanism naturally limited the number of floors rather than the height: variation. More sun means possibility of denser cities.

Warning: Introducing "social housing" into your town = injecting cancer in your body. Only to be attempted with strict rules (Fuggerei 1516)

Traditional urbanism means a multitude of transport systems, not the monoculture of modern dis-urbanism. Canals open up and connect (Fyn).

Traditional urbanism means building on street level, right out into the street. No wastage! Can't get more bang for your rigsdaler. (Aarhus)

Lower buildings and tight front streets means opportunity for small back gardens, inner yards: use for economic, gardening or recreation.

Bonus: Traditional urbanism is a boon for local economy, instantly recognizable and a magnet for tourists. Can this be anywhere but Irkutsk?

Street layout is important in how a town is experienced. In fairness I use only photos from Stockholm Old Town, pop. 3000. Sweden. Let's go!

Long streets that go on and on without any obvious end feel un-focused. These are only defensible as boulevards, towards a monumental bldg.

Long streets are best when slightly turned or twisted, combined with interesting ground floors they become attractive rather than corridors.

The best long streets are not straight, and always focused on something: in this case a parish church provides an interesting focal point.

Combine turning streets with interesting ground floors and focal points, and you get that most sought after and magical thing: a real place.

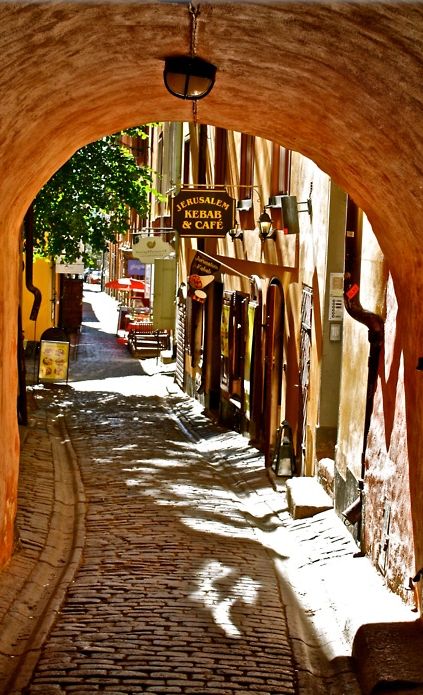

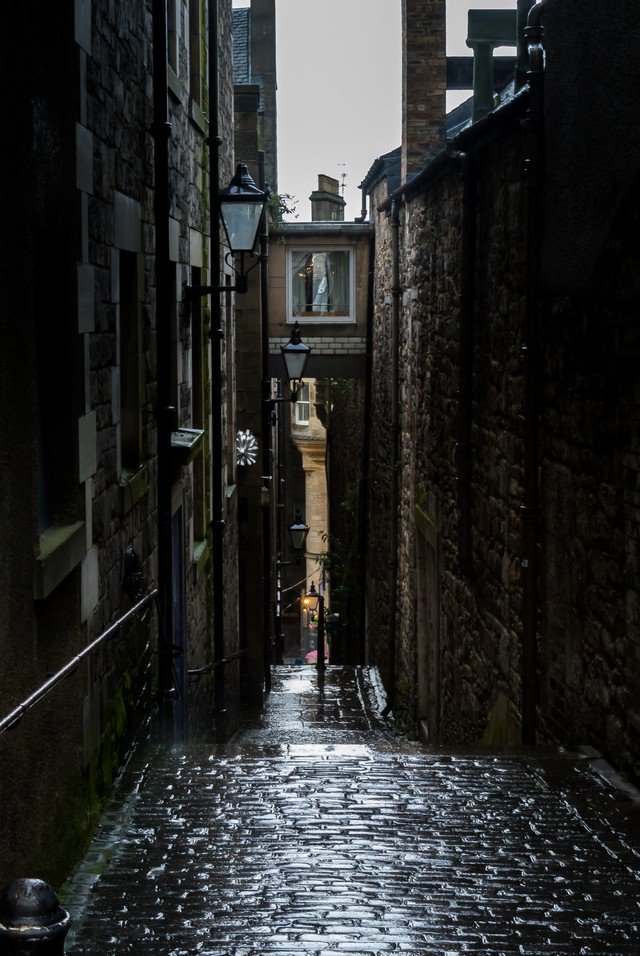

To continue: not all streets need to be run of the mill streets. Some streets can be tunnels...

...others can be stairs.

Traditional towns require almost little or no public transport. Stockholm Old town has one single subway station connecting it to the City.

Like many old towns it is located on an island (others are built like islands). Two ferry lines service it, with boats from picturesque...

...to downright gorgeous.

With 3000 inhabitants, you can walk to any point in less than 12 minutes, making cars useless (there are less than 400 parking spaces).

When we try to make good cities we go for universals, not particulars, obsessed with 1 sizefitsall, we look up when we should look down. 2/2

So far I have covered how we experience traditional urbanism (streets, layout etc.), let's have a look at how it evolves, grows up: plots.

Modern urbanism builds from the center of the plots and builds only fully realized structures, like with fossils, no evolution is possible.

Traditional urbanism starts right at the edge of the street, eventually only the center will be "open" (see Visby: mature 13th c. plots).

The buildings grow together, in shape, form, material, height, usage, organically over the centuries. No plot or bldg. is out of place.

Individual bldgs can be started small, grow towards the back, up. This bldg. in Siena was added to, improved, enlarged, from 13th to 21st c.

Modern Urbanism relies on bldgs like the “Shard”, there is nothing you could do to add or improve on this; it can only decay from here on.

Traditional Urbanism means an unruly but captivating organic mix of eras, densities, purposes and material: ecological and sustainable.

(It is really hard to illustrate plot evolution using photos of existing cities but this model of medieval Copenhagen does the job well.)

Traditional architecture is timeless: regardless of size, material and era, it is always human scaled and made by hand.

Traditional urbanism is always human scaled. It is the most energy efficient and human view of living together in civilization.

An important difference between traditional and modernist cities are the usees of color. Let's have a look! (This is Bergen, Norway)

Modernists abhorred colors for ideological reasons, and built only in the "honest" grey, white, black, beige.

Wolfe deftly explaining how it came that Modernism became architecture without roofs and eaves, breaking most fundamental rules of building.

The result we can see here, in two Dutch waterfronts: modern Amsterdam, Holland and traditional Willemstad, Curaçao, in the Lesser Antilles.

Colors contribute to creating a town harmony, both visually and in terms of materials, as in the many red tile roofs of Europe. (Dubrovnik)

Certain regions and places have become known for certain colors, for spiritual, economical or practical reasons. Here, just a few examples:

Edo Black. In old Japan, rich merchants used black lime, hand polished to a mirror sheen to protect against fire, to show their prosperity.

Falu Röd. From the 17th c. onwards, many Swedish houses were coated with a copper based pigment, durable and extremely easily maintained.

Habsburg Yellow. In a multinational central European empire, all official buildings used the same color, to create unity & visual identity.

Haint Blue. Or "Haunt" blue, is common in the US South, especially entrances, porches, windows: believed to repel insects as well as ghosts.

Color could also be aspirational: Chinese green tiled roofs are made to look the ancient bamboo rods, but today meaning longevity, youth.

But maybe the greatest use of color in architecture was achieved in medieval stained glass windows, colors that still can't be replicated.

culture we ought to build just like we did in the 13th c. (at least the Europeans). More walls, guilds: less cars, party politics. (2/2)

A present day analogy would be to cluster around factories, hospitals, universities. Build densely, farm, as close as pos. Abandon rest. 2/2

It is time to talk about the materials which define traditional urbanism: wood, earth, brick, and stone, as opposed to modern: steel, glass.

Traditional towns were sustainable, in durable easily sourced local materials, leaving no waste and fully recyclable, from source to ruin:

Near forests, making your own log houses was cheap, easy, ecological. Fire resistant, earthquake proof, naturally insulated: carbon sink!

With a bit of stucco you could even turn the humble log cottage construction into a proper neoclassical chateau, as this Swedish loghouse.

If you had less wood, half timbered houses were relatively easy to raise. The infill between the timber posts could be mud, brick, stone.

If you were successful in your business or workshop, you could just add a couple of floors: its the most flexible architecture imaginable.

In stony terrain you can use fieldstone to put up proper stone buildings, walls etc. Farmers will thank you. And its easy: just...

...pile them up! No need to use mortar if you have lots of time and space. Or...

...you can apply a bit of mortar for stronger, taller, slimmer walls. More effort but still a local product. Roofs can be made of slate.

Of course the fanciest buildings use cut stone, but looks great anywhere. These walls will last virtually forever with a bit of maintenance.

No wood, no stone, no problem! If we live in a drier climate we can make an entire town in simple dried mud brick, like Abyaneh in Iran....

...but the easiest (especially in wetter climates) is of course fired brick (this is Pennsylvania). And just as with log houses...

....they can be made to look like anything you want. Palladio made his name and fortune in the 16th c., by rediscovering brick, stucco, Rome.

Or skip the brick making part and just dig earth up and ram it in place. Like the Church of the Holy Cross (Stateburg, South Carolina, USA).

...or this gorgeous 17th c. chateau in France, Vaugirad. Rammed earth dug from the very spot it stands on. How's that for local/ecological?

...that we can build & maintain by ourselves, for ourselves, and pass on to generation after generation of our children, with good conscience.

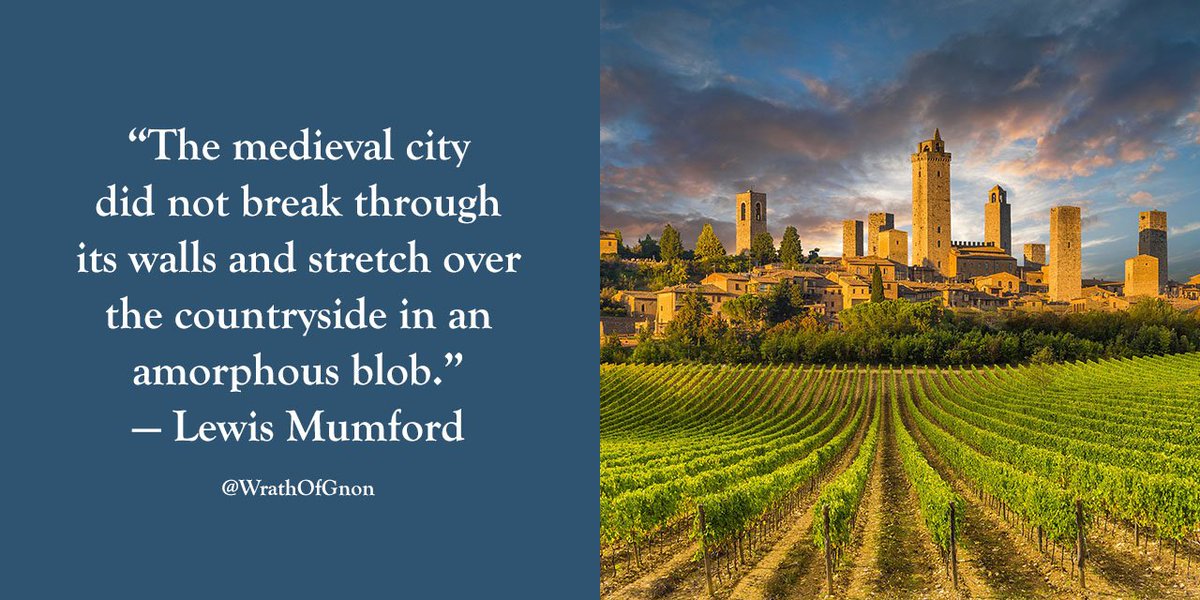

“The medieval city did not break through its walls and stretch over the countryside in an amorphous blob.”

— Lewis Mumford

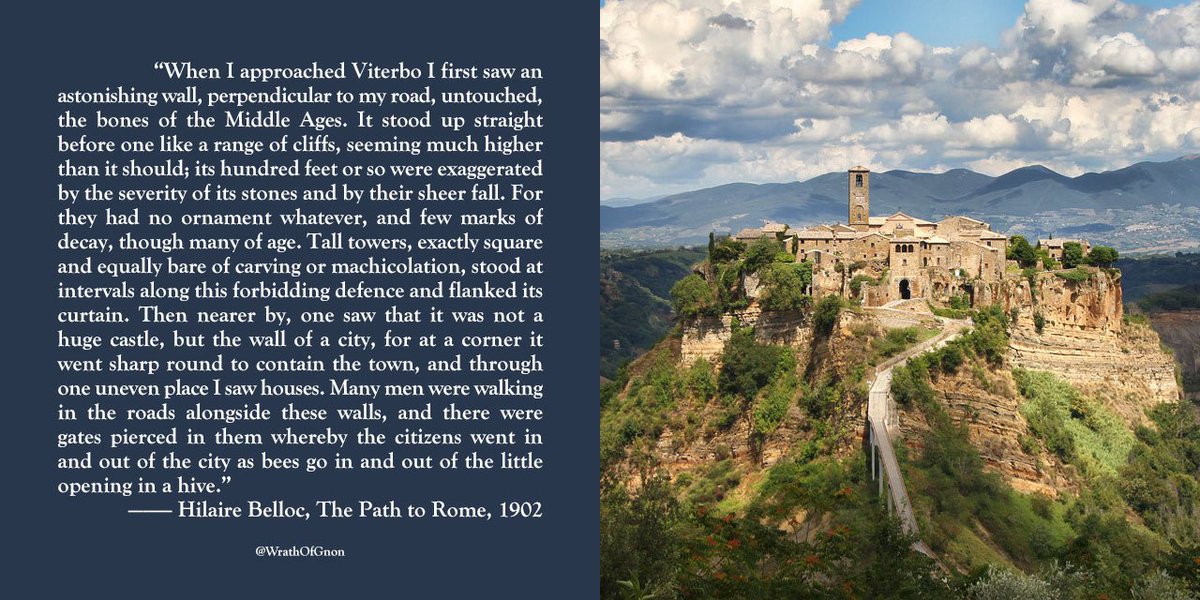

“When I approached Viterbo I first saw an astonishing wall, untouched, the bones of the Middle Ages.”

— Hilaire Belloc, The Path to Rome

Traditional Urbanism also makes use of trees and plants in a way that modern dis-urbanism completely ignores. Let's have a look.

In modern dis-urbanism, we are used to seeing "trees" like this, useless "urban parsley" that only a cynical real estate developer can love.

Even futurists get in on the game, building "gardens in the sky", like Milan's 2014 Bosco Verticale. Greenwashing has never looked so good...

...all the trouble, ecological impact of a normal concrete skyscraper, plus a bunch of new ones! (Hint: Don't walk near this on a windy day!)

In the town where I grew up there was an old tradition of public fruit trees, like here in Seville. The streets were lined with fruit trees

Traditional urbanism was gradual/organic, everything had to be both useful (to be planted in the first place) & beautiful (to be preserved).

Some towns draw world-wide interest (and tourist money) from their urban trees. The cherry trees of Kyoto is maybe the most famous example.

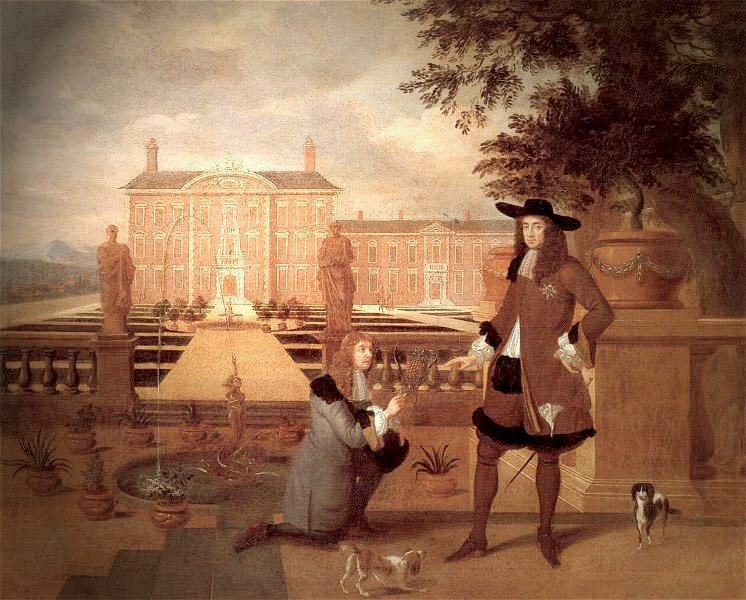

In the 17th c. it became fashionable to grow fruits and trees in purpose built "orangeries", where trees were kept inside during winter.

(Bonus: Have you heard of Pineries? A building developed in 17th c. Britain to grow pineapples. Sustainable: no electricity, no chemicals.)

Even super dense, medieval style towns can grow tons of fruits in any climate, for little or no cost. Espalier trees on south facing walls...

...while potted trees can be moved around to best suit the seasonal weather and even kept indoors at night or in winter, take out to see sun.

There's even bonsai fruit trees that produce edible fruits: the ultimate in low time preference cuisine! Delight your future grand children!

In Germany medieval towns often owned nearby forests: a dependable, stable source of income, nature conservation and access to vital wood.

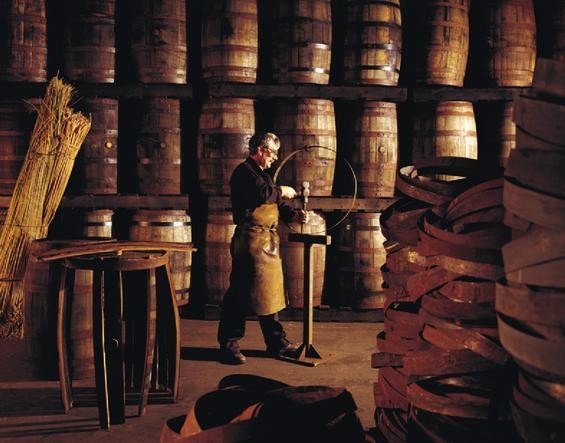

Besides fruit and edibles, town trees can provide timber and resources for buildings, artisans, craftsmen, even export...

...or be pollarded (cutting leaf bearing branches to store and use for winter feed of animals and cattle, the woody bits for kitchen fuel).

In conclusion: One quick and easy step to achieve better towns is to grow better trees in them. Trees that people can own, use, and love.

INTERLUDE: Here's a dead mall in Toledo, Ohio. Looks horrible. But what if a a group of locals decided to turn it into a traditional town?

Let's build a town just like Venice. Hundreds, thousands, could live there, with no cars. Gondolas are nicer and you can fish in the canals.

The neighbors could be persuaded to move in and the Town could acquire their land to rewild it. We'll need the wood in the future!

Let's devote the other side to agriculture. The old kind with small plots, many tiny farms. Permaculture even. But there's one big problem...

Those freeways got to go. Let's dig them up. Visitors can arrive by sail boat or barge. And why not top it up with a local currency? END.

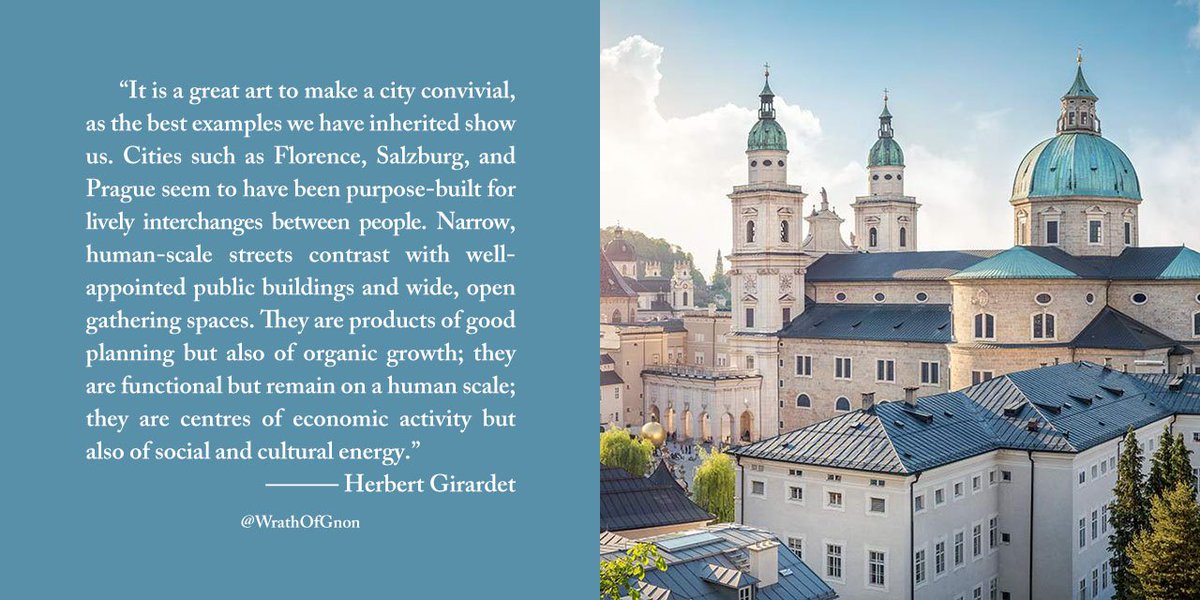

“It is a great art to make a city convivial, as the best examples we have inherited show us.”

— Herbert Girardet

Let's get serious: how did our ancestors manage to create all these charming streets? Let's look down instead of up, at what we step on.

Let's leave Europe for a while and look at Japan. In any given town, pavement material varies. Tarmac dominates, but alleys often in stone.

Big flat stones are expensive but last forever. Smaller flagstones are a cheap solution and just as charming.

Some materials are unique to one town only: Obuse is famous for its chestnuts, so they paved their streets in blocks of chestnut wood.

Not all streets need to be paved with one material, you can mix and match for maximum charm: dirt, gravel, river stone, cut stone, tarmac...

Some alleys can be left completely to nature, others can be meticulously cared for, matching the look and feel of the neighborhood itself.

Just paving a street with stone is usually enough to cut down on traffic speed, but the bicycle bravados might need even more of a nudge.

Charming streets also mean mixed use streets. Even trains and foot traffic mix in Japan, allowing for dense towns and public rail transport.

But the King of charm (and real estate value!) is water. Combine narrow streets with canals and drains for unbeatable charm.

Clean water drains help manage excess rain water, cool down towns in summer, create excellent city wide fish ponds. No pollution tolerated.

Better yet, proper canals allow for efficient noise free environmentally correct local transport and attracts tourists like nothing else.

The recipe for charming urbanism: cars ruin towns, so ban them. Move traffic out, move people in. Vary pavement to match the neighborhood...

...and above all, whatever else you do, make sure to add water to your town: canals, rivers, drains, streams, ponds. The more the better.

Our ancestors loved their cities. They loved them so much they built walls, dug ditches, raised defensive works, not only to stop invaders...

...but also to define the sustainable limits of the city in terms of space, population, sustenance.

The walls helped to create a natural hierarchy in the city, of main streets vs. alleys, gardens vs. squares, orchards vs. open fields.

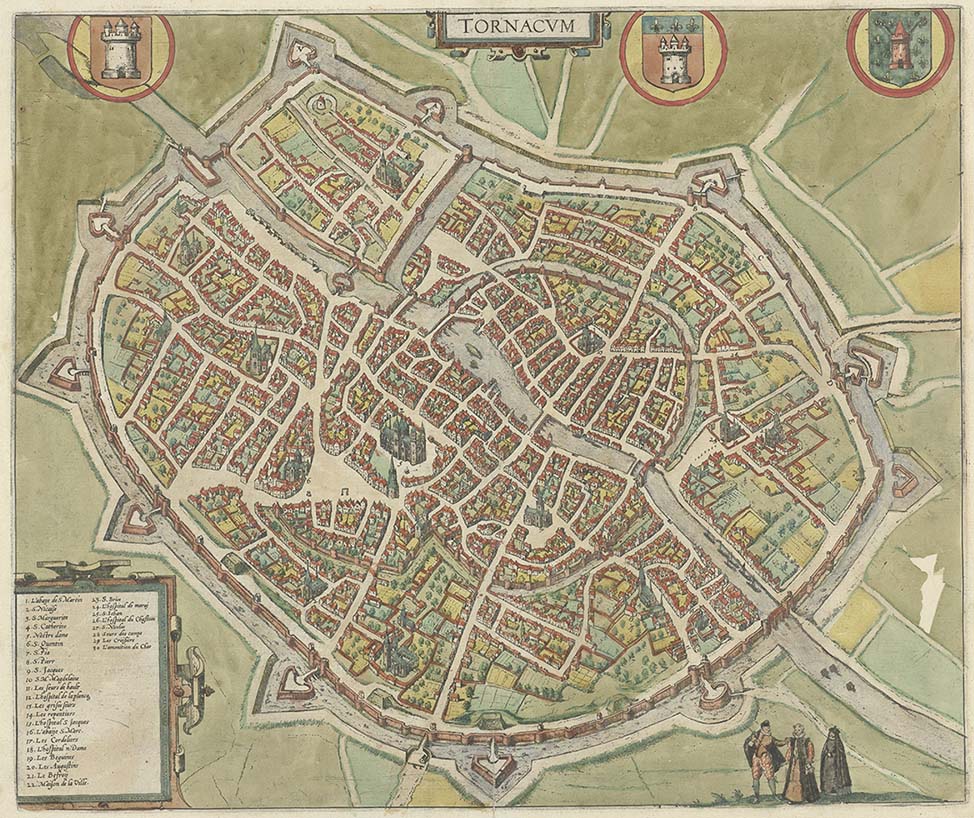

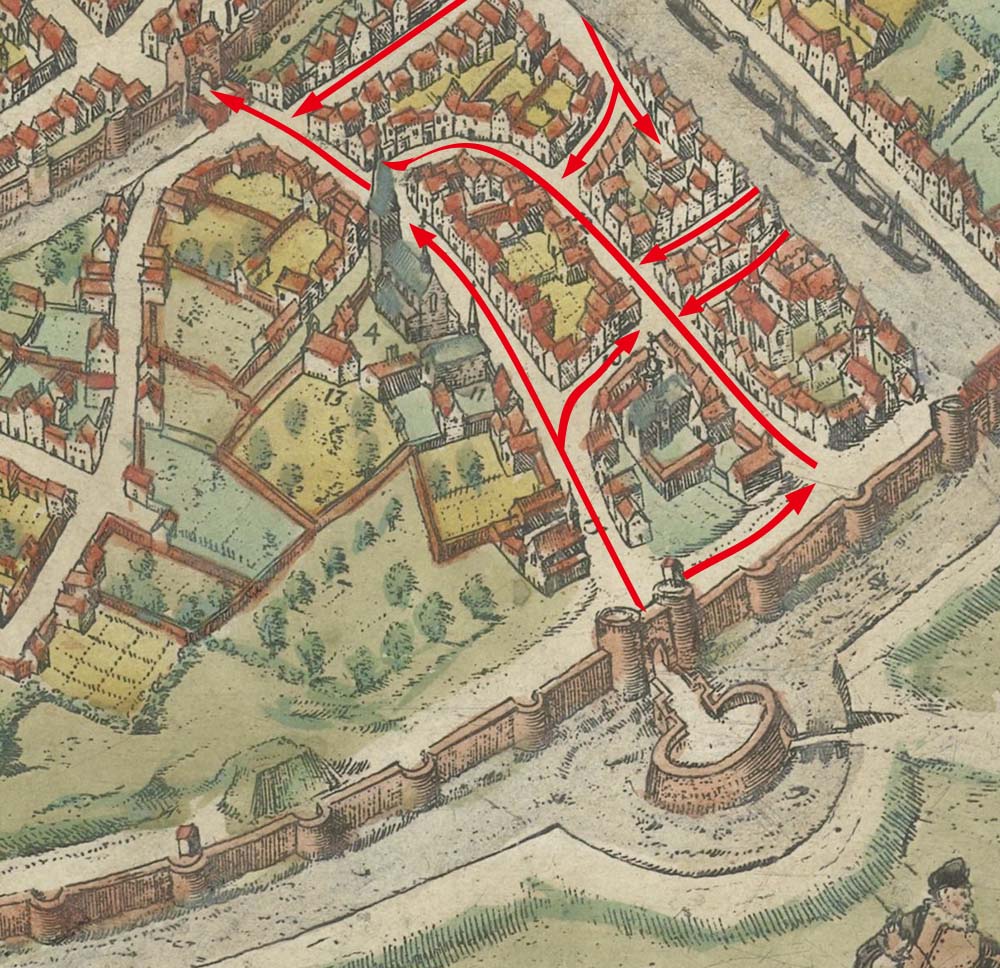

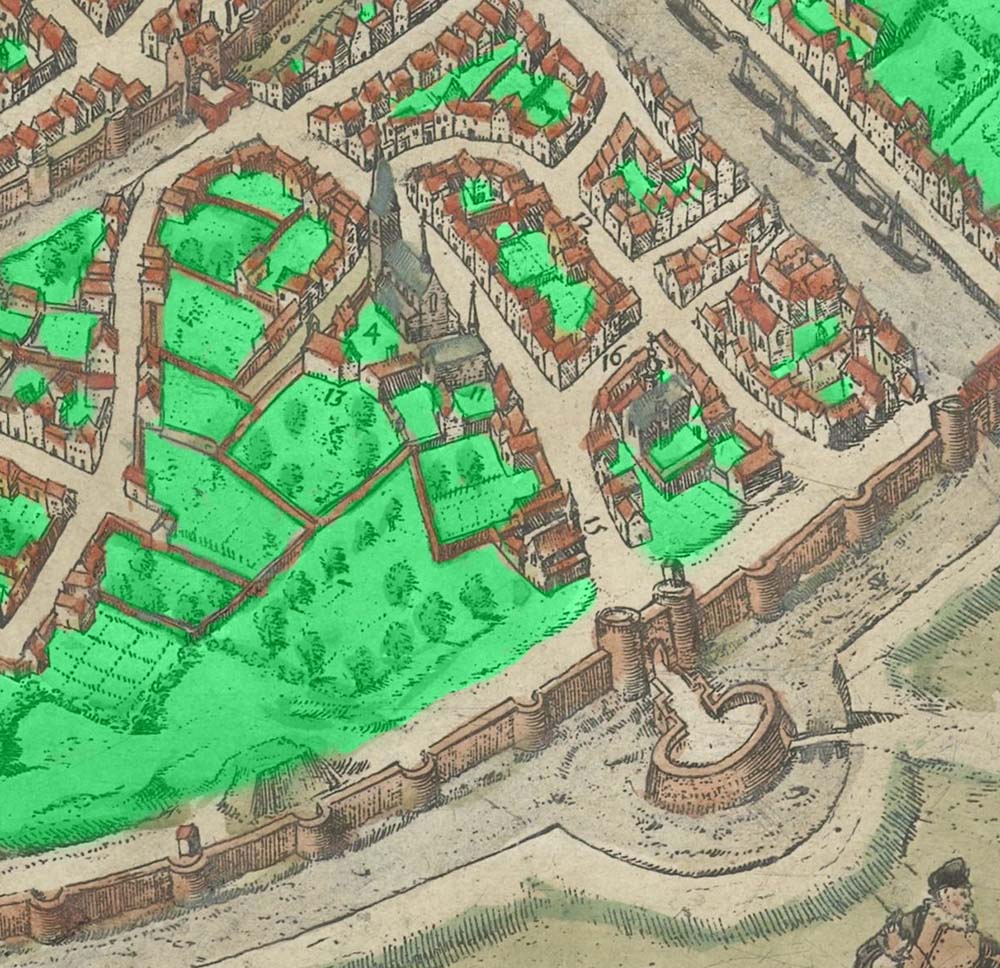

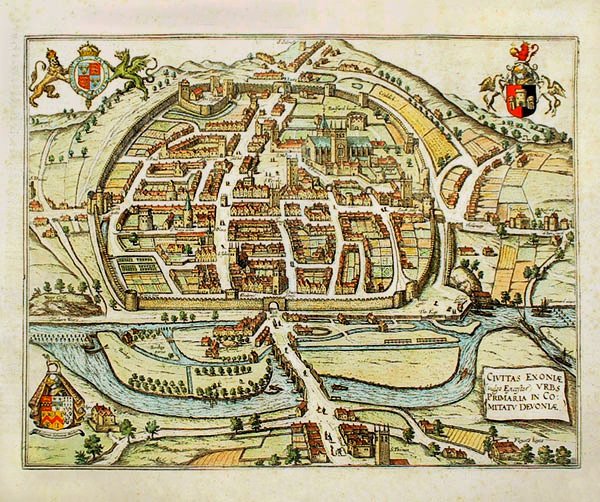

Take the ancient city of Tournai for example, in modern Belgium. It had two sets of walls. You can easily see how the main streets...

...formed naturally along the main routes (rivers) into the city. Leaving "wedges" of green space between gates and along the walls.

The green spaces (to keep animals, to grow food) gave a natural order to the city that allowed all levels of craft and commerce to develop.

Even 13th c. walled towns had suburbs, called "Forsbourg" (vl, foris-burghum), "Faubourg" (fr), "Vorstadt" (de), centered on the city gates.

Originally inns where traders, farmers, would wait for gates to open, they grew into villages of their own, invisible today but in names.

It is theoretically possible to build a great city without walls, but evidence shows us that it is very nearly impossible. So why risk it?

In order to let towns be towns and not spill into and ruin the countryside I say it is high time we start building walls again. Sustainable.

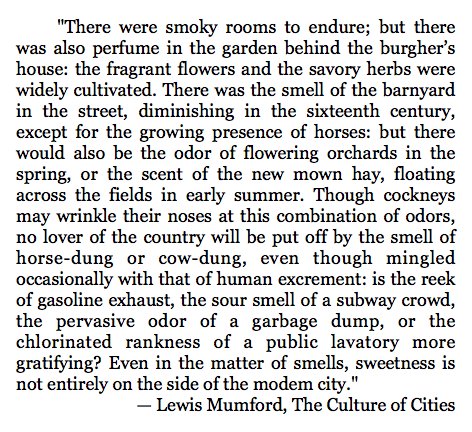

Time for some light reading: Lewis Mumford on what your senses would encounter in a medieval town. First, the nose...

Then, the ears. (From Lewis Mumford, The Culture of Cities, 1948)

Finally, the eyes. (From Lewis Mumford, The Culture of Cities, 1948)

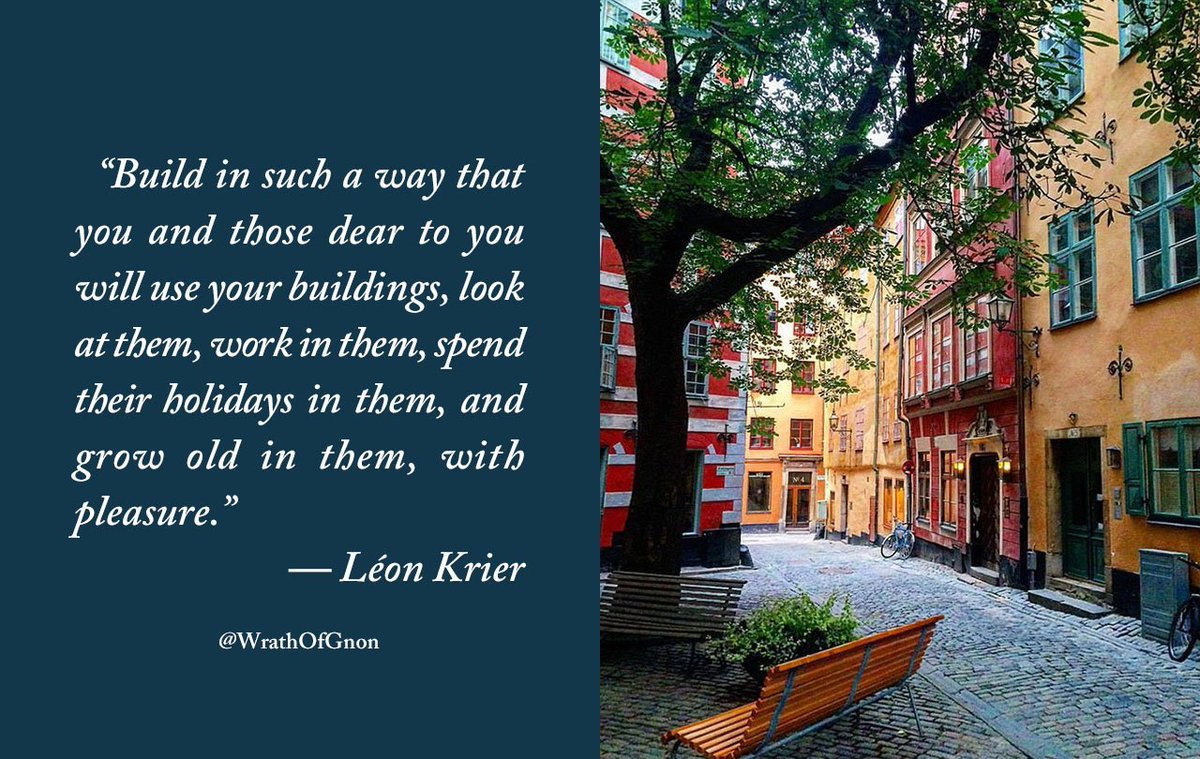

“Build in such a way that you and those dear to you will use your buildings, look at them, work in them, spend their holidays in them, and grow old in them, with pleasure.”

— Léon Krier

A few weeks into this thread the best comment/observation/mention was @jahskillen's:

Thousands of people depositing garbage for a thousand years; it all fit inside two plastic buckets.

By having tax funded social housing you guarantee that you now have a growing underclass and that the people who profit from it will make sure their numbers keep increasing. Everything you subsidize you will get more off. Good charity is qualified. Unqualified charity is poison.