Looking for Clarence Thomas

Length: • 27 mins

Annotated by Mark Isero

Gullah translation by Alphonso Brown, owner of Gullah Tours in Charleston, South Carolina; gullahtours.com.

They would call him Boy. Deb bin call um Boye.

Boy was born in low country on a one-dirt-road-in, one-dirt-road-out patch of mainland just an eleven-mile jaunt from Savannah, Georgia: Pin Point. Boye bin bohn een de loh kuntri on uh one dutt roh’d een uh one dutt roh’d out patch ob de may’n land jess uh leh’bin my’l fum Suhwannuh, Gorgee: Pin Py’nt.

Boy born on a humid, big-moon night in a shanty near the salt marsh. ’E bin bohn on uh hot big-moo’n night een uh shant’ ner’ry de salt masch. Born in a home with a single room of electricity, no running water or inside toilet. Dah boy bohn een uh hoow’s wid dis one room uh lec’trik. Boy coaxed from his mother’s womb by a midwife from another part of Chatham County, and per his mother’s mythology, Boy was too stubborn to cry. Boye slip fum ’e mama to uh midwi’f wha’ lib een uh pah’t ob Chat’um Cun’ty, ’n ’codd’n tuh ’e mah, ’e bin too stubb’n fuh mek wah’tuh come fum ’e yeye. Outside the ramshackle abode where Boy was born: the constant chorus of Moon River; birds rustling the branches of the live oaks and pines; possums, deer, raccoons darting through the woods. Outdoh de mix-up shanti weh Boye bin bohn: de repeet’n music of Moon Ribbuh; de buh’d dem shuff’lin shru de bran’ch ob de ly’b oak ’n pine; poss’um, day’uh, ’koon, dash’n shru de wood. Yonder, the seafood factory, run by the paternalistic boss of almost everybody around—including Boy’s mother and including, for a time, Boy’s soon-to-be-absent father. Ohbuh yonduh, de se’food fat’ry, wha’ run by de ol’ boss ob ’most ebbybohdy ’round yah—’kloo’d Boye mudduh ’n ’kloo’d, fuh uh little time, Boye soon fuh be ab’sent fadduh.

Boy was born the night of a wedding at the community church, Sweet Field of Eden Baptist Church, the worshipping hub once known as Hinder Me Not, a name conceived as an attestation: We will endure. Boye bin bohn de night ob uh weed’s at de town chutch, Sweet Fe’l ob Eden Baptist Chutch, de wer’shup wha’ kno’ as Hinder Me Not, uh nay’m mek up as a ’testation: We gwoi ’dure.

The moonlit night of Boy’s birth, several of his people celebrated the new union in Pinpoint Hall with drink and food and dancing. De moonlight ob Boye bir’t, sum’ ob ’e pe’pull cel’brayt de new knu’un en Pin Py’nt Hall wid drink ’n supp’n eat ’n dan’cyn.

Unbeknownst, as those denizens drank and ate and danced, they also honored the arrival of a newborn who’d go further than any of them. Unb’knownst, as dem pe’pull drink ’n grease ’e ’mout ’n dance, day also on’uh de comin’ of uh newbohn who go fer’duh dan enny ob dem.

Boy grew. Boye gro’ up.

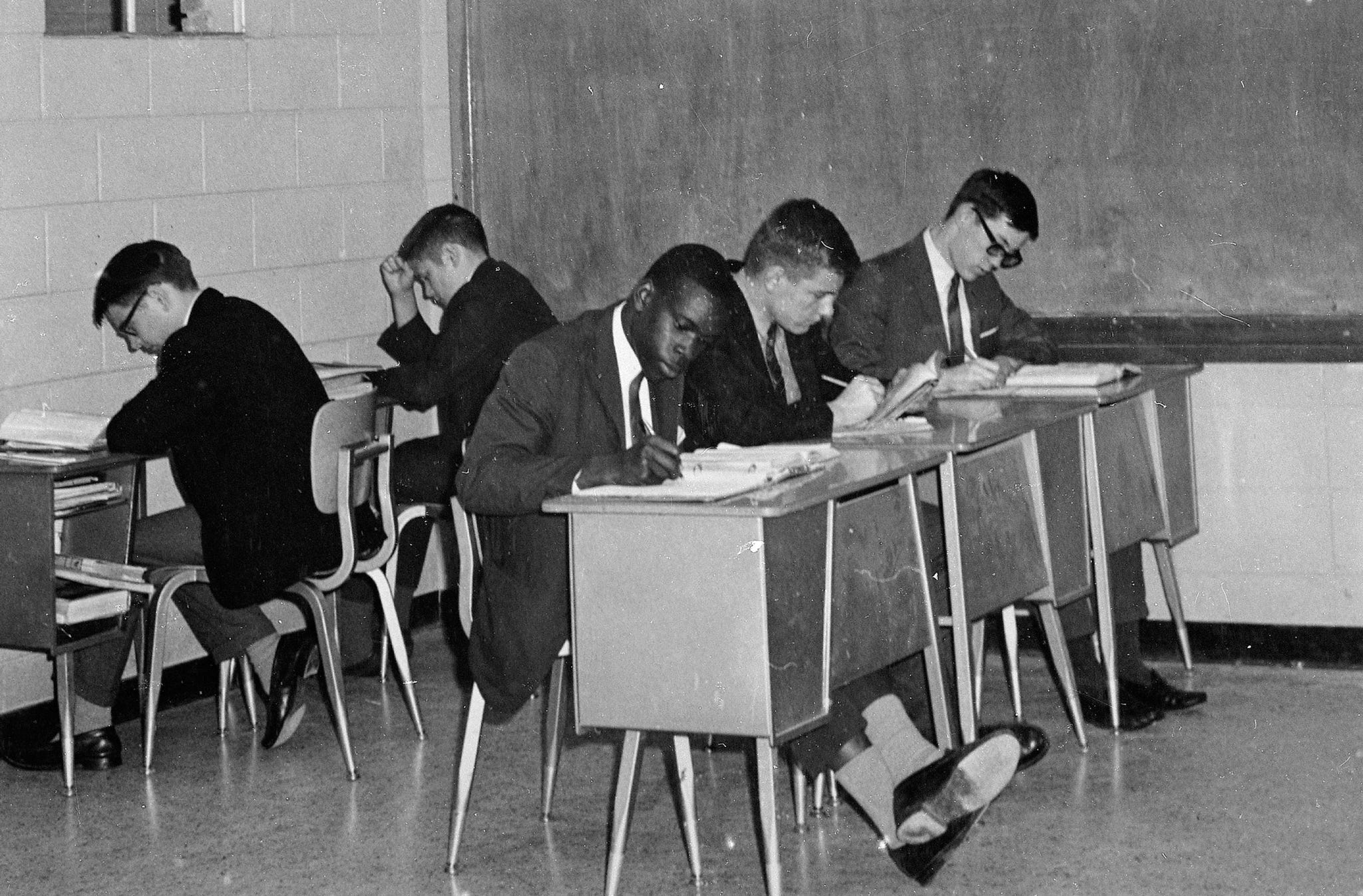

He also attended St. Pius X high school, where other kids called him “ABC—America’s Blackest Child” when the teacher couldn’t hear. A former schoolmate, now seventy-seven, quotes from memory a line from Julius Caesar he learned at St. Pius: “O Judgment! Thou art fled to brutish beasts. And men have lost their reason.”

Ike Edeani

His skin darkened to the hue of the woods at night. ’E skin duh dahk to de culluh ob de wood at night. His lips grew full. ’E lip duh full. His forehead and nose spread broad. ’E fore head ’n nose stay broh’d. His eyes set far apart. ’E yeye sit faah pah’t.

Became the features Boy would not love. Come de few’chuh Boye ain’ gwoi like.

The features of his people: the Gullah/Geechee. De look ob ’e pe’pull: de Gullah/Geechee.

Boy’s people—the Gullah/Geechee—descended from the West Africans captured and enslaved on the Sea Islands and in the low country of Florida, South Carolina, Georgia, a people who worked crops of cotton, rice, indigo. Boye pe’pull—de Gullah/Geechee—come fum de West African wha’ tek way ’n mek slave on de Sea Island ’n de loh kuntri ob Fler’duh, Sout’ Kuh’lina, Gorgee, uh pe’pull wha’ wuk fe’l ob cut’n, rice, indigo.

As freedmen and -women, those industrious folks founded Pin Point in 1896. When den bin free man ’n um’mun, dem haa’d wuk pe’pull find Pin Py’nt een 1896. Worked the land and the river. Wuk de lan’ ’n de ribbuh. Rooted themselves. Plant demself.

Boy not only bore the visage of his people but spoke their language: Gullah. Boye not only carry de fay’s ob ’e pe’pull but tawk the tongue: Gullah.

A native tongue that would shame Boy for years to come. Uh nay’tub tongue daht Boye bin sha’em fuh long time uh come.

During Boy’s less-shamed Gullah-speaking boyhood in Pin Point, he frolicked barefoot and shirtless in the fenced-in yard with his older sister and younger brother. Do’rn Boye less-shame Gullah-tawk’n boyhood een Pin Py’nt, ’e play ’round bayf’t ’n noshirt een de fence-up yaah’d wid ’e old’duh sistuh ’n young’uh brudduh.He skipped oyster shells on the river’s high tide, shot green chinaberries out of a gunlike toy called a pluffer, fished creeks for minnows, hunted the sandy marshes for fiddler crabs. ’E skip’ os’tuh shell on duh ribbuh high ty’d, shoot green chay’uh berry out ob gun-lookin’ toy call’ a pluffuh, fish krik fuh minnuh, hunt on de sand’ masch fuh de fid’la crab. Boy grew sturdy on crabs and rice, oysters and rice, butter beans and rice, shrimp and grits, stewed crab, fried crab, chitterlings, pigs’ feet, rabbit, possum, coon. Boye gro’ up skrong on de crab ’n rice, os’tuh ’n rice, de butt’uh be’n rice, skrimp ’n grits, by’l crab, fry crab, chit’lyn, pig foot, rabbit, poss’um, ’koon.

Boy, a dark, Gullah/Geechee, Gullah-tongued incipient scholar, happy-footed a long dirt road with his sister to catch the bus that would carry him to the Haven Home School, his first taste of formal learning. Boye, uh dahk, Gullah/Geechee, Gullah-tongue who ste’dy ’e head plen’ny uh time, happy-foot ’long a dutt roh’d wid ’e sistuh to fuh catch de bus wha’ carry ’em to de Hay’bn Home School, ’e fun’ taste ob straight learnin’.

One day, returning from Haven, Boy witnessed a sight that set his life on another path, that would impact the lives of untold others. One day comin’ fum Hay’bn, Boye yeye tie up on sup’in dat set ’e life on uhnudduh paah’t, dat would change de life ob untold udduhs. The tiny home where he’d been born was—the result of his little brother and a cousin playing with matches—a smoldering heap of ashes and singed tin. De little shanti weh ’e bin bohn ’n bin—de ’cause ob ’e little brudduh ’n cousin dem playin’ wid mat’che—uh smol’dren stack ob ash’ ’n sin’jup tin.

Boy’s mother moved him and his brother with her to Savannah, Boy’s forevermore goodbye to full-time living in Pin Point. Boye mama moo’b ’em ’n ’e brudduh wid she to Suhwannah, Boye fohebbuhmoh goodbye to full-time libb’n en Pin Py’nt.

He wasn’t the first Supreme Court justice to speak a native tongue other than English. Felix Frankfurter, appointed to the court by Franklin Roosevelt, was an Austrian Jew born into a long line of rabbis and spoke no English when, at age twelve, he Ellis Islanded into New York City with his family.

There’s no mention in the historical record as to whether Frankfurter hated himself for growing up speaking German, or whether the experience had so scarred him in childhood that he spent the rest of his days training his tongue to erase his past and his people.

But no other member of the high court grew up speaking a language at risk of being forgotten like Clarence Thomas did—the Gullah/Geechee man they once called Boy (the genesis of those Pin Point nicknames, and why his was Boy, is beyond anyone’s memory), who decades later would write what may be the most important thing there is to know about him: “You hate yourself for being part of a group that’s gotten the hell kicked out of them.”

You want to understand Clarence Thomas? That sentence is the Rosetta stone. Hatred directed not outward but inward, where it does the oppressor’s work for him. The man’s a human being, so his self-hatred couldn’t have been a conscious choice. But be that as it may, my concern for a single suffering human ain’t the purpose of this writing. My purpose is to try to understand Clarence Thomas not because of what the world did to him but because of what he’s doing to us.

We are on the precipice.

If you are Black if you are brown if you are Asian if you are Middle Eastern; if you’re a woman, disabled, gay, trans, nonbinary; if you are poor, a Muslim, a liberal; a returning citizen or the wrong kind of immigrant; or if you consider yourself some intersection of any of those identities, you are standing at the edge of the Grand Canyon with one foot slipped off the ledge, the other foot planted on hella loose gravel, a strong wind gusting up behind you.

We are as disunited as a country defined (or so they say) by its union can be, are a shaky democracy cleaved into camps, each living in its own alternate reality, and our ability to endure is very much in doubt. And at just such a moment of upheaval, Clarence Thomas, who for thirty years was a radical outlier on the court of courts, has won. He and his almost unfathomable view of what is just and what ain’t have prevailed. His time has arrived.

Which is to say, as much as anyone, Clarence Thomas, the most powerful Black man in America, has ushered us to this grave place.

The question is: How—and how could he?

The question is: Why?

The question is: What then is Clarence Thomas to this Black man?

To that, the man himself may well say, “Black man, all you see is race. You’ll never get anywhere that way.”

Nah. All America has ever seen is race. To pretend otherwise is to deny the truth of your and my life. Ain’t no amount of Federalist Society cant or jurisprudence dressed up in novel and abstruse legal theories or self-serving advice cautioning Black people to cease talking about race is gone change that. How can we stop talking? It boggles my mind that you fetishize a document that held in its original form that women were not and wouldn’t ever be citizens, that your/our people were not and wouldn’t ever be humans.

Like you can’t see that there were many things that document held to be true that were not true, many things that the framers, no few of them our enslavers, got incontrovertibly, manifestly wrong. Like in your “textualist” or “originalist” or “natural law”—or whatever term you apply to give a good account of your work—reading of it, you failed to divine that one of their main intents was for no Black person to set foot in a courthouse less it be in chains. Come the fuck on; that document in its best, most pristine, unblemished, unamended form is a Greatest Hits, circa 1788.

Ain’t that when they had us, Clarence? Ain’t that where they want us?

Easy for you to say, make it on your own, stop talking about race. Did you make it on your own? And of the things that fill that prodigious mind of yours, name one larger than race, Black man. I dare you.

My god, dude, what the hell happened to you?

Thomas and I are two generations apart, but I’ve been seeing versions of him all my life: dudes who never code-switch from extra-extra proper, who favor the Ivy League look and business casual, who bad-mouth Black culture like it’s a nine-to-five and exalt anything with European roots. These are often dudes who’ve been deemed exceptional, plucked up to receive elite educations, and in that Talented Tenth proximity to whiteness favor white friendships, choose a white partner.

Thomas is familiar to me in particular because, in the story of his grandfather—the man he called Daddy and who raised him and molded him—I see my great-grandfather, a fellow bootstrapping southerner. Because in Thomas’s determination to King’s English his way to respectability, I can hear my grandfather, chiding me to use “isn’t,not ain’t.” Familiar because I, too, carry the primal wound of a boy whose biological father deserted him.

But he’s also alien.

Foreign because we’ve never seen a Black man this powerful this bent on harming other Black folks. He’s alien to me because I love my people and I can see in his hardened heart he’s against us.

The question is: How—and how could he be?

The question is: Why?

The answers I’ve discovered source back to a place so small you can’t even call it a town.

“He was born right over there.”

John Henry Haynes, age of eighty-three, points a bony finger toward a ragged copse.

He peeps my raised eyebrows and doubles down, louder: “Right over there!” He tells me that was the night of the wedding—Haynes’s first cousin, Virginia, over at Sweet Field of Eden. They had a reception down the road at Pinpoint Hall—not the cinder-block building it is today, no. Back then it was wood. “They didn’t have regular paint, so they would mix limestone and water. That was the paint,” he says. Some men built a wooden arch, and the women decorated it with Spanish moss and crepe-paper roses.

“They didn’t have no band.”

There weren’t many houses then. “Nothing was here when he was born,” says Haynes. “We had a path that come through here, go from up the street to down the street. See ’cause that side of Pin Point is higher land, and this side slopes down. So that’s Up-the-street, and that’s Down-the-street,” he says, gesturing.

Go figure, everybody had a nickname growing up in Pin Point then. Haynes’s handle was Pig. Pig remembers that in the weeks and months after Pigeon had Clarence—Pigeon was what everybody called Leola Williams, Clarence’s mother—the older kids would run in and look at him cooing or sleeping. If Pigeon asked them to, they would pull a thin curtain from a window and drape it over his crib just so, to keep the flies and mosquitoes off.

There were no diapers—no one had the scratch for such opulence. Instead, they tore up sheets, washed and reused them. The moody Spanish moss hanging from the trees—their toilet paper. There were two water pumps—one on the slab down at the crab-picking factory, one over at the edge of Miss Harriet’s property.

“It was some hard times,” Pig says. “You had to be disciplined. In those days, you couldn’t walk by a person’s house and not say, Good morning, good evening. Yes sir, yes ma’am. You walk by them and you don’t say nothing? ‘What’s wrong with your mouth, boy?’ We were seeking the Lord, man. I was baptized in this creek right here.”

At high tide, Clarence and the younger boys would skip oyster shells across the surface of the water.

“We made our own toys,” Pig says. “We made scooters.” He retrieves a Bic pen and some white paper from the glove box of his truck, sets the paper on the hood, and starts drawing—precise, old-man drawing with straight lines. “We had these gallon cans, like a paint can, from the oysters. You take the tops of the cans, those your wheels . . . . We put a nail here, right there . . . . Put a string right there, okay, right there . . . . We cut another board . . . .” His aged hands pull the pen across the paper, and a scooter is taking shape. “Then that’s the string there. You wanna nail this down tight . . . . Okay? You take half of this, half of that, and put it there—see, this is the bottom . . . . Then you just get on, and you push it!”

He straightens and looks at his drawing. “We made a lot of these.”

Hard times, yes, but good times, too, if you didn’t know no better. “We raised up on oysters and crab,” Pig says. “We was blessed. We didn’t know how rich we was, man. Going to school, kids would call us crab pickers. ‘Here come the crab pickers.’ But we had a good life here, man. A good life.”

Pig was working for a roofing company in the early 1990s, forty years after Boy moved away. “When I came back off a break, it was change-of-shift time,” Pig says. “Guy named Herbert Sanders, out of Rincon, Georgia, he come running and said, ‘John Henry! Your homeboy’s appointed to a judge, man!’ I said, ‘Who?’ ‘Clarence!’ I said, ‘What?’ He said, ‘Yeah!’ I went home and seen it on the news. Mm-hmm.”

If he saw Clarence today, I ask, would they hug, would they catch up?

“You can’t get near him,” Pig says.

Thomas writes in his memoir of a life-changing moment at one of the Catholic schools he attended: “Father Coleman told me matter-of-factly that I didn’t speak standard English and that I would have to learn how to talk properly if I didn’t want to be thought ‘inferior.’ ”

Can you imagine the curriculum of those fine parochial schools? What you think they taught young Clarence about the Civil War? What are the chances they educated him on the Gullah/Geechees’ rich West African heritage? How many stories about Black life do you think they assigned? What color was the savior that hung in his chapel?

James Baldwin wrote, “A child cannot be taught by anyone whose demand, essentially, is that the child repudiate his experience, and all that gives him sustenance, and enter a limbo in which he will no longer be black, and in which he knows that he can never become white.”

The older Thomas got, the further and further he absconded from his Blackness. The more Thomas revealed his anti-Black sentiments, the more and more bigoted white people propelled him in his career.

The further and further he drifted into that limbo.

After dabbling in a couple of seminaries, Thomas gave up on the Catholicism of his upbringing, which got him damn near excommunicated from home. He attended the College of the Holy Cross, in Worcester, Massachusetts, starting in 1968—Father Brooks, who would soon become the head of the school, drove hundreds of miles in search of Black students to help diversify the campus. Thomas hung with Black Panthers and even helped start the Black Student Union, though he wrote later that he half-wished he hadn’t been a part of Black students’ cleaving from the rest of the student body. (“Did we really want to do to ourselves what whites had been doing to us?”)

He met Kathy Ambush, a coed from a nearby school, and they married the day after he graduated. Thomas’s grandmother, Aunt Tina, and his mother made the trip, but not Daddy. A few years later, he and Kathy had a child: Jamal Adeen. Thomas had chosen Yale from a trio of Ivy League law-school acceptances, a decision he swears to this day was a mistake off the belief, as evidenced by the lack of job offers on the other side, that people thought he got in only because he was Black. He ended up working for the Missouri attorney general, an old-money midwesterner named John Danforth, who—surprise—also went to Yale Law. He followed Danforth to Washington, D. C., when Danforth was elected to the United States Senate. In both roles, Thomas refused to work civil-rights issues.

Then, in 1980, he accepted a gig to speak at a conference for conservatives and met a young writer for The Washington Post, Juan Williams. Williams wrote about Thomas, and as lore has it, the story caught the eye of the new Reagan administration. President I-don’t-owe-Black-folks-nothin’-y’all-didn’t-help-me-get-elected offered Thomas a job: the Department of Education, but (joke was on us) working civil-rights issues. Thomas balked but took it, though it was short-lived because something bigger opened up: running the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. That’s right, a government agency charged with combating workplace discrimination.

Over the next few years, he divorced Kathy and met the love of his life, Virginia “Ginni” Bess Lamp, at a conference on affirmative action. As EEOC chairman, Thomas did everything he could to nix the commission’s role in resolving class-action lawsuits against employers. Would you believe he refused to recognize mass discrimination, that he instead favored cases in which an individual claimed discrimination—person by person, that was all he was interested in. Fuck helping whole groups who had been targeted by prejudice. That’s not what government’s for.

Safe to say, the Republicans found their guy.

In 1990, George H. W. Bush made him a federal judge. Sixteen months later, he was standing on the lawn of the president’s Kennebunkport estate as Bush called him “the best qualified at this time” to succeed civil-rights icon Thurgood Marshall on the Supreme Court.

It was obvious to anybody with eyes and ears and a mustard seed of sense that Thomas had been chosen as a blunt instrument of Black oppression. Thomas could’ve been a Black hero, could’ve extended the legacy of the paragon he replaced, could’ve inspired generations of young Black kids to bend America’s arc toward justice. Instead, he’s taken it upon himself to forge a legacy from the negation of Marshall’s work.

Adecades-old sedan sits curbside on a Pin Point street. It’s missing tires and caked over with so much dirt and grime that its windows are opaque. The car moves as if there’s someone inside it, but I ain’t about to stare. We huff through muddy grass past one manufactured home and mount the steps of another. We knock and wait, knock and wait, and nothing. All around us there’s the detritus of old things, furniture, household items, this-and-thats. Someone has turned a chicken coop into a kennel for a barking dog. We knock again, wait, wait, and when we don’t hear anything beyond the door, we decide to leave.

The man we’re hoping to talk to is kin to Thomas and a close childhood friend, still living in the old neighborhood.

To our luck, on the way back to the car, a truck pulls up with furniture and who knows what else. My editor tells the man that he came by the day before and that a woman told him to return. He asks if the man has a few minutes to chat about his old friend Clarence. The man pauses from hauling items off his truck and tilts his head at us.

“Nope, I don’t think I can do that for you,” he says.

“It would just be a few minutes,” my editor says. “We know you’re busy.”

The man, who is tall and wiry with salt-and-pepper stubble, grabs a chair off his truck and places it before him. “You know, people always coming around here asking about Clarence, wanting an interview about Clarence. And then they go off and do their thing and make money. Everybody else getting rich, and I’m still right here,” he says. “I’m still right here struggling. I like money. What’s in it for me?”

My editor and I shoot each other a glance. Who can blame the man for wanting compensation for his time? This scene leaves little to no doubt that he could use it. In fact, if you asked me to describe rural poverty, it would be something like this.

This is the poverty that Thomas left behind, that he escaped. And I can’t help but wonder how the world would look now if instead of this man hefting used furniture off his truck into his manufactured home, it was Thomas.

“We hear you,” I say. “We just want to get it right.”

“Gentlemen. I can’t be of service to you. I won’t be able to help you,” he says, and there’s a stern period in his voice.

My editor asks if the man needs help unloading the couch from his truck.

Call it pride, but he declines.

If you look back at Thomas’s life, almost every one of his achievements has been tainted by deep disappointment and/or hurt. From his early days in Catholic school, where he was shamed for speaking Gullah and looking African. To St. Pius X high school in Savannah—when the teacher wasn’t in the room, kids would call him ABC, “America’s Blackest Child.” To when he entered the seminary and the shock of his bigoted peers disaffected him into quitting his pursuit of the priesthood. He lost his grandfather Myers Anderson when he left the church, a man who saw over the horizon to a future he could not abide. “I’m finished helping you,” his grandfather told him. “You’ll probably end up like your no-good daddy or those other no-good Pin Point Negroes.” Thomas’s grandfather spited him for the rest of his days—which suggests something about how long Thomas might harbor a grudge over a disappointment or perceived wrong—and punished him for quitting the seminary and the life of service that would have kept him in Savannah and with his people, instead of highfalutin up north to school, learning the King’s English, and adopting a foreign system of beliefs. His grandfather made his disapproval clearer by skipping Thomas’s graduation from both Holy Cross and Yale, as well as his first wedding—a trio of hurts.

Thomas’s incredible gifts were always in service of something. He’s shared that he was excited about school from the get-go, back when he and his sister, Emma Mae, caught the bus to the Haven Home School in Pin Point, but if he was ever a textbook philomath or creative for the sake of being creative, that’s unclear. His intellectual gifts, from the time his grandfather enrolled him in private schools, were in service of making proud the most important person in his life—or, rather, not disappointing him—but soon and since, Thomas’s gifts have been used as a means of proving to white people that he could compete with them, that he could succeed by their standards, that he was worthy of their acceptance.

The most searing moment of Thomas’s public life—and the most notorious words that will ever come out of his mouth, more famous than any sage concurrence or dissent that will ever be attributed to him—came at almost the very minute that America and the world learned his name: the watershed of watersheds.

By 1991, Thomas was a professed conservative, one subject to concerns of whether he’d adopt a more complex view on the bench. At the time, he railed that Anita Hill’s sexual-harassment claims were a fiction, which was itself a backlash against his heterodoxy; that the hearings were a plot by liberal Democrats to defame him and keep him off the Supreme Court; that the scandal was yet another instance of the man working to keep a Black man in his place, even as he prepared to replace a Black man on the Supreme Court; that all of it was a crucible that amounted to “spiritual warfare.”

In his memoir, Thomas describes having an epiphany before testifying later that day in front of the judiciary committee. He is lying across a couch in the office of his mentor, Senator Danforth, with only Danforth and Ginni as company.

“The thoughts that had been running through my head for the past half hour crystallized into a single phrase.

“‘Jack,’ I said, ‘this is a high-tech lynching.’”

“‘If that’s what you think,’ he replied, ‘then say it.’”

Thomas goes on to describe entering the caucus room of the Senate building and delivering the following rebuke as if the Holy Ghost itself were speaking through him:

“This is a circus. It is a national disgrace. And from my standpoint, as a Black American, as far as I am concerned, it is a high-tech lynching for uppity Blacks who in any way deign to think for themselves, to do for themselves, to have different ideas, and it is a message that, unless you kowtow to an old order, this is what will happen to you,” he said. “You will be lynched, destroyed, caricatured by a committee of the U. S. Senate, rather than hung from a tree.”

Nevernohow does what happened to Thomas compare to Nat Turner hanging from a tree in 1831, to doctors flaying his corpse to make a coin purse or boiling the rest of him for grease. Never ever should what happened during the hearings be analogized to the fate of Mary Turner (no relation), who in 1918, for criticizing the lynching of her husband, was hung upside down from a tree, doused in motor oil and gas, and set ablaze; who, eight months pregnant, had her unborn baby sliced out of her belly and stomped to death; and who, after those odious tortures, was riddled to a quicker death by hundreds of bullets. It mustn’t slip your mind: Nobody murdered Thomas, shaved his head, and used his hair as part of the macabre stuffing of some southerner’s chair.

That, that, that is what it meant to be lynched.

“High-tech lynching” will be the most famous words Thomas ever utters in his life, words that opened him a gateway to this very point in time. And a sad paradox is that he workshopped those words with a powerful white scion. Matter fact, said it to Danforth as if the senator were at all capable of commiserating. He makes no note that his in-person audience was a Senate judiciary committee composed of fourteen white men. Not to mention he has described spending most of his life up to that point refusing any kind of preferential treatment on account of his Blackness, attacking the very affirmative-action-esque policies that propelled him at many junctures in his life.

For all his railing against those policies, for all his opposition to civil rights and to expanding rights for more and more Americans through a living Constitution, for all his “I’m a free Black man who wants to be judged on my merits alone,” in a moment of supreme crisis, Thomas played a Black card, a near unimpeachable tactic.

That was about the last Black card that Thomas played. With it he entered that nether realm where, as Baldwin describes, he was no longer Black but in which he could also not be white.

Been to D. C. umpteen times, but this is my first time visiting the Supreme Court. For hours I’ve wandered the grounds, harboring the wispy hope that I might see somebody Black or welcoming entering or leaving, that by some stroke of fortune I might meet a person who knows the strength of his handshake, who can confirm if his purported rapport with the people who work in the building goes both ways.

No such luck.

Instead I find the marble palace surrounded on all sides by an eight-foot black fence; find people jogging along First Street; three young women with access badges on lanyards laughing bright as the sky, a man posing a little boy in front of the fence for a photo, a Capitol police officer standing under an umbrella with a handheld electric fan angled at his face.

On another circuit around the grounds of the court and Capitol Building, I see a group passing the side of the Russell Senate Office Building, chanting, “Abort the court! Abort the court!” The ragtag group of seven looks weary—it’s so hot it seems the sun’s sole purpose is wringing sweat—which is understandable, but in truth they also appear defeated.

And none more so than the lone Black woman among them, slim with a nose ring and short Afro. She sits on the edge of a concrete wall and holds her signs for me: a small homemade one that reads "forced pregnancy is torture" and a printed placard that says "enough is enough: end gun violence." The Supreme Court is over her shoulder, just behind some maple trees. Not to mention, we’re right across the street from the building in which Anita Hill testified and Thomas denounced her as a bald-faced liar. The young woman and I do not speak a word to each other, but her signs and solemnity remind me, as if I need reminding, how Black women so often have suffered the brunt of Thomas’s decisions.

Here I’ve come to the place where the man does his work, a place he might be inside right now, and I couldn’t be more distant from him.

John Danforth shares a story about a time a few years ago when Thomas spoke at a luncheon of the Bar Association of Metropolitan St. Louis. In the midst of being hustled from the luncheon to the reception, he stopped to engage a janitor and, while U. S. marshals stood by and event handlers urged him to leave, kept right on chatting with her. “When you talk to Clarence Thomas,” says Danforth, “it’s as though you are the only person in the world.”

Paul Pressly, director emeritus of the Ossabaw Island Education Alliance, recounted a story about witnessing Thomas’s kindness after he had given a speech at the Savannah Country Day School. “At the end of it, he did something nobody had done,” said Pressly. “The head of the school was going to present the diplomas and [Thomas] said, ‘No. I don’t want you to do that. I want to present the diplomas.’ And he called out their names individually and embraced each child.”

At a recent conference of the American Constitution Society, Justice Sonia Sotomayor said of the colleague she admits to disagreeing with the most, “Justice Thomas is the one justice in the building who literally knows every employee’s name . . . . He is a man who cares deeply about the court as an institution, about the people who work there.”

Make it make sense that a man who cares for the individual seems to care so little for them when they comprise a group—for their rights, health, safety. His preference for the power of the state and nullifying rights for the individual has been profound—in the past few months alone he’s helped knock down the constitutional right to privacy (Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization), remove the ability to sue police for failing to Mirandize suspects (Vega v. Tekoh), expand the reach of the Second Amendment and make it even more difficult for local governments to regulate guns (New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen), roll back environmental protections (West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency). And how do you think he’ll vote this fall when the court has the chance to gut more voting-rights measures with its approval of state gerrymandering (Merrill v. Milligan)?

Dr. Cornel West once said, “Justice is what love looks like in public.” Thomas’s actions say he can love someone in private but that that capacity doesn’t extend to the public. Not only does his vision of justice not look like love of the masses; it often looks like hate. Far as I can tell, a part of Thomas’s hate is knowing his hypocrisy is so obvious. That the slightest scrutiny reveals that, for all this talk about the importance of Black families and nuclear households, he divorced his first wife (their son later came to live with him and Ginni); that for all his criticism of affirmative action, he’s been its incontestable beneficiary; that in his recent concurring opinion targeting unenumerated rights as errors to be corrected, he failed to mention Loving v. Virginia (1967), which established the right for him and his dear wife to interracially marry. As I see it, an elemental part of Thomas’s rage is living with the empirical truth that, by and large, the people who should be his people despise him; that the white people for whom he has risked so much only pretend to love him; and furthermore, that to nurse the succor of that facade, he must do more harm to vulnerable people. The sacrifices he’s made for power and the compromises he’s made to salve his primal wounds have left him a man without a country or a true tribe.

It’s a mere 580 miles but also a universe between Thomas’s mythologized-to-the-hilt birthplace of Pin Point and the Fairfax, Virginia, suburb where he now lives. On a humid July morning, I pay a visit to Thomas’s doxed address, not because I think I’ll coerce an interview, catch him out for a stroll, or spy him pulling out of his driveway but because I’m keen on what his home and his neighborhood suggest about him.

Just inside the subdivision, there’s a small "no trespassing" sign and a larger sign that announces the road as private. Past those warnings, an island planted with crape myrtles divides a two-way lane. Three-story brick estates sit back from the lane with small national parks of towering beech and alder and sweet gum and birch trees for front yards. While I’m still weighing the odds of a misdemeanor charge, I see a couple (or, rather, they spot me) dressed in all-white athletic gear walking my way. They wave and smile the broad smiles of people who believe they’re safe, and I wonder how they feel about their neighbors, if they attribute any of that sense of safety to Thomas, if they judge him and Ginni as noble or ignominious.

For the trees and how far back it sits from the road, I can’t see Thomas’s home, but I’m convinced I’ve reached it for the tinted black Suburban parked in its driveway and another conspicuous black Suburban just to the side of it. With my heart beating a gavel in my chest, I wary a glimpse of the officers and keep right on driving until I reach a cul-de-sac. Parked, I see recycling bins teeming with cardboard, see an antediluvian rocking chair on somebody’s porch, see a cat slink from one yard to another as if he owns every square inch beneath his paws.

This is the idyllic place Thomas returns to from a job that, of late, needs securing by that eight-foot fence, the place he retires to on days he and his colleagues announce the usurping of more rights; this is where he catches shut-eye while, because of his actions, a ten-year-old rape victim must travel from Ohio to Indiana for an abortion. Indeed, this is where Thomas has ended up—the culmination of a life that saw him broken and twisted, then given unimaginable power, power he has used to project that brokenness on the world, again and again, with horrific consequence.

On my way out, I notice a little flag flying from Thomas’s mailbox. It’s insignificant until it dawns on me that, though several neighbors fly stars and stripes from poles above their porches, his home is the only one with a mini version jutting out of a mailbox.

What’s Clarence Thomas signaling about his Americanness, about his America?

It makes me none in the moment, because in the end, what I find when I find Clarence Thomas is the sad, solitary existence of a man turned so inside out that he looks for comfort in the worst possible places and finds what he thinks is solidarity with the people who most detest what he might have become were he still Boy, were he still living down there with Pig and Pigeon and the man unloading the couch from his truck, all of them gettin’ along day by day, with no help from anybody.

1948

Clarence Thomas is born in the Gullah/Geechee community of Pin Point, Georgia, to M. C. Thomas and Leola Williams. M. C. doesn’t stick around long.

1954–55

Thomas’s brother accidentally burns down their home. The family moves to Savannah, where Leola leaves her sons with her strict parents, who raise the boys.

1964–68

Thomas spends his final three years of high school and his first year of college preparing to be a priest. After a year at Immaculate Conception Seminary in Missouri, he transfers to the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, which was trying to add Black students.

1970

Thomas, who frequently wore combat fatigues in college, marches in a protest from Boston Common to Harvard Square, where a riot breaks out—fires, looting, mass injuries.

1971

Thomas marries Kathy Ambush just after graduating from college.

1973

Jamal Adeen Thomas, Thomas’s only child, is born.

1974

Thomas graduates from Yale Law School. His grandparents do not attend, citing too much work to do back home.

1974

John Danforth, Missouri attorney general and a fellow Yale Law grad, hires Thomas—and in 1979, as a U. S. senator, hires him again, as an aide.

1980

Washington Post writer Juan Williams praises Thomas after meeting him at a conference. The story is credited with introducing Thomas to the Reagan administration.

1982–90

As chair of the EEOC, Thomas is criticized for ignoring class-action suits. He also says Black civil-rights leaders “bitch, bitch, bitch, moan and moan, whine and whine” instead of trying to work with the administration.

1984

Thomas divorces Ambush.

1987

Thomas marries Virginia “Ginni” Lamp, whom he met at a conference on affirmative action. Soon after they met, she asked him how he coped with the EEOC controversy. He showed her a prayer he recited daily.

1991

President George H. W. Bush nominates Thomas to the Supreme Court. After a ninety-nine-day confirmation process that included accusations of sexual harassment from former colleague Anita Hill and accusations of racism from Thomas, the Senate confirms him, 52–48.

2006–16

In a remarkable streak, Thomas does not ask a question from the bench during arguments before the court.

January 6, 2021

On the day of the riot at the Capitol, Ginni Thomas cheers demonstrators on via social media, later saying that the posts were written before the violence began. Her connections to right-wing extremists spur calls for her husband to be removed from the court.

June 24, 2022

In a 6–3 decision overturning Roe v. Wade, Thomas writes, “In future cases, we should reconsider all of this Court’s substantive due process precedents.” Some commentators opine that, given his power and influence, Clarence Thomas has essentially become the de facto chief justice.