The Crow Whisperer

Length: • 19 mins

Annotated by Mark Isero

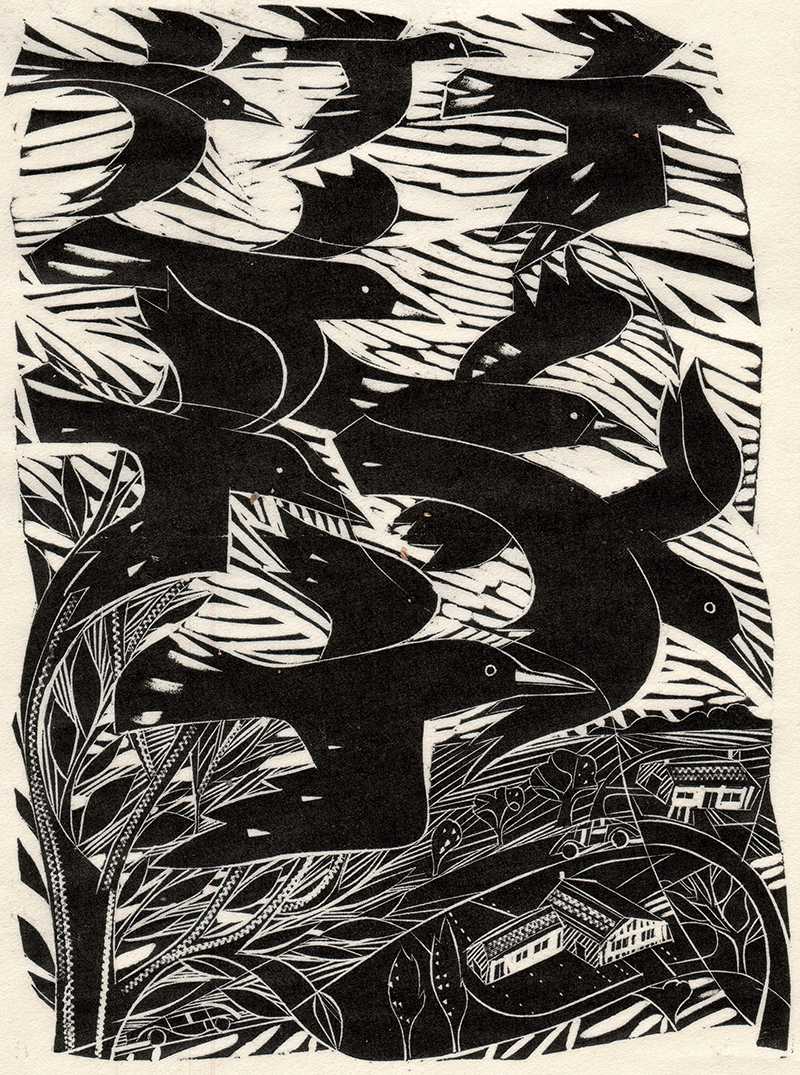

Linocuts by Jonathan Gibbs for Harper's Magazine

When the crow whisperer appeared at the side gate to Adam Florin and Dani Fisher’s house, in Oakland, California, she was dressed head to toe in black, wearing a hoodie, gloves, and a mask. This was a few weeks into the coronavirus lockdown, so Adam initially took her garb to be a sign of precautionary vigilance. In fact, it was a disguise. “It’s so the crows don’t recognize me and—no offense—start associating me with you.”

Adam found this odd, but he and his wife were out of options. Things had gotten bad. Two days earlier, the couple had just woken up their four-month-old, Lina, from a nap when they heard a concerning ruckus behind the house. At the far end of the yard, Dani—who is one of my oldest friends—spotted a menacing cloud of crows, cawing and encircling their dog, Mona. It looked as though they might carry her away or, worse, kill her on the spot. (“Do you know what a group of crows is called?” Dani later asked me, stricken. “A murder.”) She shouted, raced toward Mona, and dispersed the crows just long enough to get her dog inside.

From then on, each time Adam or Dani walked onto their back deck, a crow would call out and the murder would reappear as if summoned, squawking so loudly that it was impossible to carry on a conversation. Sometimes the crows would dive-bomb them or attack Mona when she went out to pee. When Adam took the dog for a walk, the crows swooped low and followed them. He tried walking Mona in other neighborhoods, but the crows terrorized him there too. Adam and Dani felt under siege. They worried for Lina’s safety. “The crows are like the Mafia,” Dani told me a few weeks into their ordeal. They’d stopped going outside, she said, unless it was absolutely necessary. And because of the pandemic, they couldn’t really go anywhere else.

The day Dani rescued Mona from the crows, a neighbor thought he’d spotted a fledgling in Mona’s mouth before the murder first descended. Dani and Adam weren’t so sure—they had never seen Mona attack a bird before. But it nevertheless occurred to them that they might be on some kind of crow hit list. Through online research, Adam learned that crows have an uncanny ability to recognize humans, assign them moral qualities, and pass this information on to other crows, even to future generations. Desperate, Adam took to Reddit. If you’re at war with the crows, post after post advised, your best option is to move.

“What do you know about crows?” he posted on Facebook. “Namely, conflict resolution?” Friends and family members expressed concern and offered suggestions (“Try a squirt gun?” his mother wrote). A few neighbors chimed in with their own recommendation: he needed to talk to Yvette Buigues, the local crow whisperer. Adam wrote her a message, and she promised to come over right away.

The crows descended, cawing loudly, as soon as Buigues entered the backyard the next day. She began, she told me later, by offering soothing words, and sending the birds unspoken messages: that she came in peace, that she was there to help. They quieted almost immediately. Buigues poked around the area where the crows had congregated, which Adam and Dani had been avoiding. She spotted a fledgling hidden in the brush. Its wing was mangled and bloody, hanging from its body by mere strands. It peeped with fear and hunger. As a new father, Adam was moved almost to tears by the sight of the injured young bird.

The murder looked on as Buigues chatted calmly with the fledgling, which then staggered toward her, lugging its throbbing wing. She put out her hand and the trembling crow walked right into it, opening its beak in search of food. In all likelihood, said Buigues, it wasn’t going to make it.

Buigues told Adam they had two options: take the bird to a vet to be euthanized and leave the crows an offering of peanuts—a favorite corvid treat—or simply provide the fledgling with a comfortable way to spend its final hours. Adam opted for the latter, and Buigues asked him to fetch a box and line it with soft towels. She then gently placed the bird inside, along with a small dish of water. Buigues sent a few silent messages of apology and thanks, then slowly backed away, leaving the baby bird in its makeshift coffin.

A few hours later, the bird was gone—whether snatched up by a predator or retrieved by the parent crows, Adam and Dani weren’t sure. They scattered some birdseed around the emptied box, worrying that they’d be punished for choosing to leave the fledgling exposed. But when they stepped outside, the murder kept its distance. The couple could sit on the deck, and even in the shade of their trees, without bother. Something had shifted.

Last May, as the number of coronavirus deaths continued to rise, many of the animals that live among us in cities and towns—residing in gutters and trees and parks and crawl spaces—had their worlds turned upside down. City centers were empty; dumpsters were no longer filled with scraps of food; fewer cars were on the road; neighborhood parks were thick with people who would otherwise have been working or at school. If it weren’t for the coronavirus, Mona would never have been outside that morning chasing fledglings, because Adam and Dani would have been where they usually were in the middle of the day—at work.

Around the same time, news began circulating in Oakland about a turkey named Gerald. He had taken up residence at the Morcom Rose Garden along with his mate and chicks, and was behaving aggressively toward humans. He clawed and chased and left bruises; he stole food; he threatened children and ruined picnics; he jumped onto one woman’s back as she was trying to flee. City workers relocated Gerald to the nearby hills, where I like to go running, but he soon returned. The parks department secured a permit for his execution.

Elsewhere in Oakland, a solitary peacock roamed the streets screaming. SFGate ran an article quoting a resident named Jesse T.: “It’s so loud inside my house it literally feels like he is inside my house.” In San Francisco, the quiet streets were overrun with coyotes. On Martha’s Vineyard, turkeys colonized the rooftops of empty houses, causing traffic jams of gawking rubberneckers. Antlered deer marched down boulevards in Paris, wild pigs wandered around suburban neighborhoods in Turkey, kangaroos hopped through downtown Adelaide, rams tore through villages in Wales, and pumas prowled the streets of Santiago before they were sedated by authorities and dragged back into the wild. A friend reported that her husband’s office in New York had been taken over by rattlesnakes.

At my own house, about a month into California’s shelter-in-place order, my husband spotted a hummingbird nest in the lower branches of the birch tree in our small backyard. The nest was well hidden, almost entirely concealed by drooping branches and abundant leaves. Each morning we’d watch, spellbound, as the hummingbird sat on its eggs, roosting, waiting. What else did we have to do? A co-worker reported that she too had found a hummingbird nest in her backyard. Soon after, other friends made the same discovery. It seemed like a delightful coincidence. But who knew how long these birds had been there without our knowing?

These stories of animal invasion—even the more menacing ones—were a balm, a necessary distraction from the horrors of the news. And yet something more profound seemed to be at stake. What if dive-bombing crows were not just a reflection of the pandemic’s disruption but a glimpse of a world where the boundaries between humans and the rest of the animal kingdom had blurred? As I began to imagine a post-pandemic world—one with a more equitable education system, health care for all, accessible public spaces, a less exploitative economy—I wondered whether there was also an opportunity to rethink the relationship between humans and the natural environment. After Adam and Dani told me about the crow whisperer, I considered whether she might be uniquely able to help me imagine what this new relationship could look like. At the very least, it would give me something to think about besides the plague.

One morning in July, I texted Buigues to tell her I was interested in learning more about human-animal conflict mediation. She wrote back that same day, saying she would be happy to talk. “Right up my alley,” she said.

I had imagined Buigues as some kind of ethereal new-age mystic, but she turned out to be a rowdy fortysomething raconteur with a gravelly voice who loves to cuss. In addition to being a pet trainer and cranio-sacral therapist working with animals and their owners, she is a painter. Her subjects include pets and monsters, as well as crows.

Buigues told me that she had been transfixed by animals since childhood, often finding them better companions than people. In her twenties, she went on a hiking trip in Utah with her boyfriend. Ravens followed them everywhere, as if seeking her attention, and she began talking to them. Buigues and the birds seemed to have a common understanding. (The boyfriend found this so disturbing that he broke up with her.) Years later, her husband came across a stranded fledgling crow in the middle of a dog park. She was sure it would be mauled to death, and told him to bring it home. She named the bird Carl and nursed him back to health, fed him, chatted with him, and eventually helped him learn to fly. He lived with her and her husband for over a year, eating lavish scrambled-egg breakfasts and sleeping in an aviary they built outside.

Eventually, some wild crows took notice and began circling their yard in the mornings. Carl became curious, training his eyes skyward. One day Carl took off. He returned four days later, careening into Buigues’s chest. He had a gash in his head and had lost some feathers. “That bird had gone off and had so much fun and gotten into some real exciting trouble,” she said. It was as though he’d taken a rumspringa. “He was basically like, ‘Take me back! I’m not ready!’ ” Carl stayed with them for another six months before the murder returned and Carl left for good. After that, Buigues was even more popular with the neighborhood crows. Carl seemed to have communicated that she was an ally.

Buigues is wary of calling herself a psychic or a medium. “I’m just an old punk rocker,” she says, “who happens to be able to communicate with animals.” She carries a fair dose of skepticism about her power—perhaps it’s just common sense, she wonders, or deep intuition. Sometimes she freaks herself out. She has tried psychically beaming treatments to horses from many states away, only to hear from their owners that the animals were acting very strangely at the exact moment that Buigues’s treatment was under way. Once, while waiting for her husband to pick her up from Costco, she tried communicating with her dog, Cecil, just for fun. “The dog park was good,” she heard the dog tell her. “We saw Debbie, but I didn’t like her cookie.” That sounded unusual to Buigues; her dog loved treats. But sure enough, her husband pulled up and told her that they’d run into their friend Debbie. When she gave Cecil a cookie, Cecil spat it out. “It’s trippy,” Buigues told me. “I can’t explain it! I just sometimes know exactly what the fuck my dog is thinking.”

I wanted to see how Buigues worked in person. After months and months indoors, steeped in Zoom meetings and books, I was craving a firsthand magical experience. “Come on over anytime,” she told me when I asked. “I’ll pour you a shot.”

A week or so later, Buigues texted me saying that one of her regulars, Pamela Fong, was willing to let me observe a session with her bull terrier, Ernie. Fong lives up a winding road in El Cerrito, in a handsome house overlooking the vast, parched hills of Wildcat Canyon. “You’ll see my car parked out front,” Buigues texted. It was a Mini Cooper with a vanity plate that read 2dingoes, after the breed of her dogs. Buigues, dressed entirely in black, greeted me in the driveway and took me inside to meet Ernie and Fong. I could see immediately that the house belonged to Ernie. Baskets of toys were scattered around the living room and bedroom—new ones arrived every month via the subscription service BarkBox. Portraits of bull terriers hung on the wall, including a custom work that Buigues had painted a few years earlier.

We walked outside to Fong’s wide, sunny deck so that we could remove our masks. Buigues took a seat on a lawn chair and Ernie hopped up beside her. She slowly ran her hands along his spine, twisting his tail slightly this way and that. “There we go,” she’d say. “Let it out.” And Ernie would emit a great big yawn, or a yelp, or a prolonged, chirruping cry. Then he’d leap up and spin in place or circle the deck before coming back for more.

It did seem as though he was speaking to her, and that she, in turn, was deciphering messages lodged deep inside his body. The yawns and cries, Buigues explained, were emotional releases, similar to what humans might emit during a particularly intense massage or chiropractic alignment. Yet Buigues was barely touching him. Eventually, as she was working on him, he fell into a deep, unmovable sleep. After one more adjustment, he awoke and, with a small bark, signaled to Buigues that he was done.

“Isn’t it amazing?” Fong asked me as we watched Buigues. Ernie was a stiff dog who often hobbled on his walks. Thinking it could do no harm, Fong had conscripted Buigues for help. “I didn’t believe in any of this crap,” she said. “But then you just see it, and you know. She has a gift.” After the treatments, Fong said, Ernie runs like a puppy again. This was no illusion. Buigues was doing something, even if it wasn’t flashy or grand. It felt like a quiet little miracle.

When I asked her to decode what was happening as she drew her hands along Ernie’s spine, Buigues struggled to explain it, as if interpreting another language. She was following the currents of his energy, she said, attempting to unravel metaphysical knots and twists. She understood the limitations of her explanation, but that was the best she could do. It was just something she felt.

For most people who purport to communicate with animals, the ability is considered a lost art, something that was widely practiced before the advent of modernity, before mechanization and urbanization. This was, in part, a matter of necessity: reading animals helped humans evade predators, find prey, and monitor the needs of livestock. As the balance between humans and the nonhuman world has shifted, the thinking goes, we have become less attuned to natural signals—which isn’t to say that one can’t recover and master these skills today. “If you’re quiet, you’ll hear them,” Buigues told me.

“I think every single person has the ability to communicate with animals,” Marji Lee Pearson, an animal healer based in Mill Valley, explained. “But for many people, their minds are so busy, they never stop, they’re always on their computer or their phone.” Laura Stinchfield, something of a celebrity among animal mediums, told me, “If they would just get quiet and centered, and just sit with the animal, they would pick up exactly what the animal feels and what the animal is saying.” Stinchfield, who calls herself the Pet Psychic, appears frequently on the TV show AnimalZone, in which she travels across California to help resolve conflicts between pets and their humans, stunning owners with her ability to read their animals’ minds. “Empathetic people are doing this all the time,” she said. “They just don’t realize it.”

Magical thinking had a particular appeal in the early months of the pandemic, but so did the clarity of science. I wrote to Frans de Waal, a leading primatologist, asking whether he’d be willing to discuss the potential scientific underpinnings of the kind of communication I’d witnessed between Buigues and Ernie. I received a quick response: “But I am sorry I don’t believe in telepathy.” It was all he wrote. I persisted, however, and he kindly agreed to talk to me about what, from his perspective, I had seen.

De Waal is a specialist in ethology, the biological study of animal behavior, a field that emerged in the 1930s. In contrast to behaviorism, which asserts that animal behavior can be explained in terms of incentives, rewards, and punishments, ethology posits that animals are innately intelligent, rather than simply programmable. It has only somewhat recently been considered mainstream science. “I had trouble with the idea that animal behavior could be reduced to a history of incentives,” de Waal wrote of his early days as a biology student. “It presented animals as passive, whereas I view them as seeking, wanting, and striving.”

I recounted Adam and Dani’s story and asked de Waal whether he could explain what had happened. In response, he told me about the widely discredited biologist Rupert Sheldrake, who coined the term “morphic resonance” for a theoretical exchange of feelings and knowledge between animals through time and space. According to this idea, rats would pass a test more easily if nearby rats had already passed that same test; dogs would know when their humans would walk back in through the door no matter the schedule they kept; and pigeons would be connected to their home via “something rather like an invisible elastic band.” De Waal explained that another scientist had tested Sheldrake’s theory by building a roost for pigeons on a truck bed. When he moved the truck out of sight, the pigeons found themselves homeless; they couldn’t trace their way back. “You need controlled experiments,” said de Waal. “And as soon as you do them, they fall apart.”

To ethologists such as de Waal, some animal communicators are classic grifters, manipulating their marks by inferring the obvious or telling them what they want to hear. (One famous pet psychic told me that my cat was exceedingly handsome and then proceeded to insist on just how stunningly well-behaved he was—mere hours after my husband had stepped in a steaming pile of cat shit on our living-room floor.) But biologists, like psychics, tend to believe that we vastly underestimate animal intelligence and the intricacy of their emotional worlds. Animals can cry and joke; they can hold celebrations and burials; they feel jealousy and monogamous love. Many animals understand justice and unfairness (a baboon will be happy with lettuce for a reward until he sees that his friend has been given grapes, a far tastier prize). A trendsetting Zimbabwean chimpanzee named Julie once decorated her ear with a blade of grass, and fellow chimps adopted the fashion as though she were a middle school It Girl. Bowerbirds, meanwhile, adorn their homes with attractive objects in order to entice a mate, painting rocks with berry juice to make them more beautiful. Dolphins call one another by name, while chickadees and prairie dogs form complex words using a kind of additive grammar. Crows recognize the particular proclivities of their beloveds, and, as I now know, seek retribution for perceived harm.

Animals communicate in myriad verbal and nonverbal languages, de Waal emphasized, which humans are capable of learning to decipher. Likewise, animals pick up on human cues for their own protection, and out of something like love. “Animal intelligence is beautiful enough, amazing enough,” de Waal told me. “You don’t need to add fictional elements to it. It’s already by itself quite remarkable.”

De Waal, Buigues, and the psychics I spoke with ultimately agreed on one thing: communicating with animals requires deep, sustained attention. The pandemic has established favorable conditions for this kind of communion. For those of us who aren’t essential workers, time has slowed, our vision has shrunk to that which is visible outside our newly compelling windows or inside our drastically reduced interiors. The hummingbirds transformed from backyard attractions into potential companions, even interlocutors. Perhaps, if I focused in just the right way, I could reach them. I tried to quiet my mind, to tune into their frequency. We love you, we love you, I’d think, as loudly as I could. You’re welcome here.

Often, when the weather was nice enough, I’d take my computer onto our deck to work feet away from the nest. Just after I sat down, no matter what time it was, the mother would leave the nest to go hunting. But she never flew away without first hovering a few feet from my face, looking directly at me. Initially I thought she was trying to establish her territory, to urge me to move. But after a while it seemed more a gentle request to guard her nest while she was gone. Whether I understood this by witchcraft, scientific decoding, or wishful thinking, I wasn’t sure.

Over the next few weeks, the baby hummingbirds emerged from their shells and turned, slowly, from beaked, miniature dinosaurs into feathered balls and then, finally, into fully formed birds. The bigger they grew, the more food the mother had to find, and the more often she would leave them (I would swear on it) in my care. Her message seemed clear: watch over the nest while I’m gone.

Eager to know what Buigues would make of my progress with the hummingbirds—and, admittedly, interested in whether she could help my cat, Bodie, who had been waking us up several times a night, biting at his stomach, and attacking us if we pet him in the wrong places—I invited her over one August evening.

She showed up again dressed in black, sporting a black mask, wide-rimmed black glasses, and a black beanie pulled over two braids. “It’s a bit harder with cats,” she explained, settling into a chair in my backyard. “Because they’re made entirely out of cat.” Still, Bodie took to Buigues readily, jumping into her lap the minute she called him. She placed him on the table, one hand resting gently on his neck, the other on his tail, and murmured into his ear. She ran her hands up and down his spine, feeling for, as she put it, “hot” areas—which could mean inflammation or pain. His hips, she said, seemed out of balance. This was one of the sensitive spots that my husband and I avoided touching. He could have an old injury, she said, or it could be a site where he held some emotional pain. “Animals store pain and memories just like we do,” she said. She placed her hands across his hips and neck, slowly bending and stretching his spine.

As Buigues worked, Bodie was alert but still. She occasionally gave a nod, or a “there we go,” to which Bodie would meow, slip from her grip, and give a shake. But he never bit her as he did us, and, after a few minutes of rest, Buigues was able to coax him back onto the table for more. Was it magic? Was it illusion? Did it matter? And could I ever know? Eventually, having had enough, Bodie hopped the fence. “He’s done,” Buigues said.

I told her that one day, when I was outside working, Bodie had curled up in an empty flowerpot a few feet from the hummingbird nest. The mother left her post, secured my attention, and buzzed only a foot above the sleeping cat, spinning a few swift circles. She flew back to me again, then back to the cat, then back to me. Got it? she seemed to be saying. Watch my babies, and keep your eyes on this terrible sleeping beast. I asked Buigues whether she thought this made sense or whether I had been imagining it.

“Oh yeah,” she said. “But I’m kind of surprised you didn’t move your cat inside. That’s clearly what she was asking you to do.” I felt a little ashamed.

A few weeks later, I went to visit Adam and Dani. They were in great spirits. In the backyard, Lina bounced in her chair. Aside from the occasional caw, the birds left us alone, provided we didn’t venture to the spot where the fledgling had been found. Meanwhile, the local peacock seemed to have calmed down; perhaps he had grown accustomed to the revised ways of his human neighbors. Gerald the turkey had managed to avoid his would-be executioners. Before they could capture him, he had vanished into thin air, as though he’d received some kind of tip-off. It seemed that animals were better at noticing than people were. Perhaps nothing much had changed after all.

In my own backyard, the baby hummingbirds practiced flying by gripping the bottom of the ever-deteriorating nest while flapping their newly formed wings. The one we called Big Brother took off first, taking its wings for a spin and occasionally perching on a higher branch while another chick practiced in apparent encouragement. We watched all of this, congratulating them and cheering them, until one day, the nest was empty, and they didn’t come back.

I was bereft. For months, the birds had been my focus, my main source of optimism. I planted snapdragons in an attempt to lure them home, and kept a small fountain running in case they needed water. I bought more flowers, and then some more. Please come! I would silently beg of them as I opened the door each morning. It was stupid. But my world had become so small, and they offered the company I missed, along with a dash of magic, as if a curtain had been pulled back to reveal a secret world.

A few weeks after the hummingbirds disappeared, I saw one take a sip from the fountain. It buzzed away as soon as I ran into the backyard. Later, I spotted another one drinking from the tangled vine along our fence, and then from the new little flowerpot I’d arranged in hopes of drawing them back. Hello, hello! I’d shout inside my mind every time they showed up, hoping they could hear me, thinking that, perhaps, they might. Come back anytime! They returned again and again. It was probably the flowers, the fresh water—but on the other hand, I’d offered those things because I knew they wanted them. It was nice to think that if I called out to these interspecies friends in some ineffable language, they might hear me.

Buigues understood how I felt. She told me about an outdoor punk festival that took place in her neighborhood roughly six weeks after Carl had left for good. She watched a few sets, then got hungry and decided to bike home for a snack. But when she approached the spot where she’d locked her bike, it was surrounded with people staring in wonder. There, on her bike seat, was Carl. He flew straight to Buigues and perched on her shoulder. She began to weep, and some onlookers started filming. She dug an energy bar out of her pocket and offered it to him.

“Isn’t he handsome?” she said to the crowd.

“Is that your pet?” someone asked.

“No,” she said, “He’s not my pet, he’s just my friend.”

They spent the rest of the afternoon and evening together. During the final set, he perched on her shoulder as she danced under the open sky, jostled by the crowd. As she biked home that night, he alternated between soaring a few feet above her and catching a ride on her helmet, whirring over the concrete together. They hung out in the backyard, and when it was time for sleep, set off for their respective homes and said goodbye.

In November, I got a text from Dani. “Holy shit,” it read. Attached was a photo taken outside her back door, where someone or something had placed a single, unshelled peanut. She was sure it was the birds. A peace offering? A request for more treats? A threat? Dani dispatched Adam to the store for peanuts. When he returned, they put out a small pile of nuts on the deck for their corvid neighbors, as if to say Thank you, or We’re sorry, or, at the very least, We know you’re there and we’ll tread lightly. They may not know how to talk to the birds, exactly, but they have a sense of how to keep the peace. The birds, so far, seem satisfied. Message received.